Clarence Timbrell Collier

Clarence Timbrell Collier was born on 24 August 1893 in Geurie, New South Wales, near Dubbo. He was the third child of Thomas and Sara (Lyons) Collier. He had four sisters – Susan, Myrtle, Marion, and Ida – and he was the much-loved only son (two brothers had died in infancy). His second name is in honour of his respected great-grandfather, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Richardson Timbrell who came to Australia with the British 58th Regiment in the 1840s.

Clarence’s father, Thomas, was the stationmaster in Geurie from 1890 to 1906 when it was the end of the rail line being built to Dubbo, the major transport hub for the area. After that, the family moved to Sydney when Thomas was appointed stationmaster at Gordon Railway Station on Sydney’s North Shore.

Early Years

Clarence was a brilliant student. He attended Geurie Public School and completed his high school education at the Fort Street Model School when the family moved to Sydney. While there, he was Captain of the Debating and Drama teams.

He continued to excel scholastically, and at age 20 had completed his Bachelor of Laws at the University of Sydney, becoming the youngest person to achieve such a degree at that time – but too young to practise as a lawyer.

While at university, he tutored various people who became judges themselves, for example, Justice Dovey, NSW Supreme Court (who was Margaret Whitlam’s father). He was also a captain of the Rugby team and spent 18 months in the Sydney University Scouts program, a university-based militia battalion.

Around this time, war fever was building. This was described in the DIGGER magazine as follows:

The Hon. Vernon Treatt MLA, then a law student at Sydney University, recalled the excitement which prevailed in both class and common rooms and the efforts of even the youngest students to enlist. He stated that the Law School removed one embarrassing obstacle by moving exams forward to facilitate enlistment. In his words, the students were ready and eager to take up arms.

New Guinea

Adding two years to his age, Clarence enlisted in the Australian Naval & Military Expedition Force (AN & MEF) on 13 August 1914. The official World War 1 historian, Charles Bean, commented that the first recruits who went into the AN & MEF tended to be “adventurous” types.

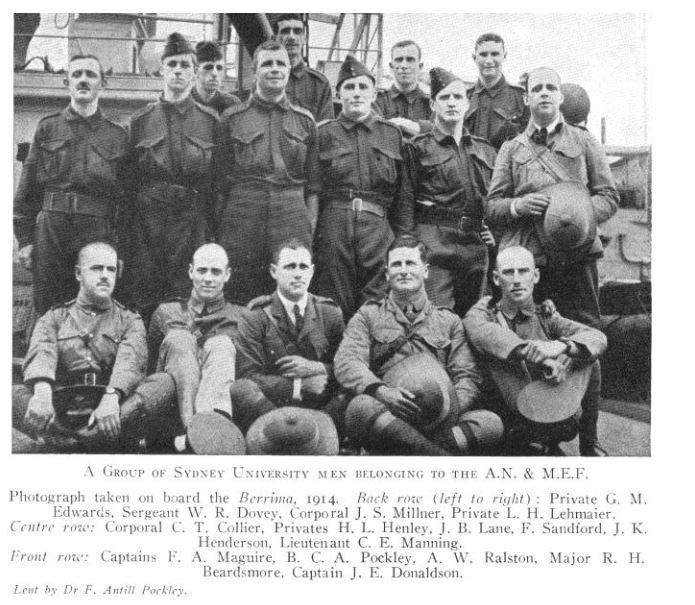

Clarence was assigned as a corporal to the Special Tropical Corps, G Company of the 1st Infantry Battalion, a battalion about 1000 men strong. Less than a week after enlisting, he embarked on 19 August embarked on HMAT Berrima, headed to New Guinea. Clarence was among a good number of Sydney University men.

The soldiers briefly trained on Palm Island before arriving in New Guinea where their key task was to destroy the German wireless stations used to communicate with the German East Asiatic Squadron. The capture of the station at Bita Paka was completed in September, not long after their arrival.

With the major objective completed, some of the law professionals were engaged in the newly established British legal system in New Guinea. There was one incident involving Clarence (somewhat amusing, in retrospect) where he was punished for giving soldiers free legal advice and was demoted to Private.

With the completion of the military objectives, Clarence returned to Australia and was discharged on 5 March 1915.

Egypt and the Western Front

Clarence remained keen to serve and enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force on 24 August 1915 and was assigned to the 9th Reinforcement, 18th Battalion. At the end of October, he applied for and was granted a commission. He was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant on 1 Dec 1915.

As with his stint in New Guinea, he was soon to depart Australia, and on 20 Jan 1916 he embarked on HMAT A54 Runic, headed for Egypt. After a month at sea, they arrived in Alexandria on 26 Feb 1916.

With thousands of new recruits arriving in Egypt and new battalions being formed post-Gallipoli, there was a good deal of movement of personnel between units. Clarence was transferred to the 53rd Battalion in early May in Ismalia and assigned to C Company, under the command of Major Victor Sampson.

The 53rd was soon called to support the Western Front and so their 32 officers and 952 soldiers left Alexandria on 19 June 1916 on the Royal George. After arriving in Marseille on the 28th, they had a 62-hour train ride to Thiennes. It was noted that their “reputation had evidently preceded them”, as they were well received by the French at the towns all along the route.

Battle of Fromelles

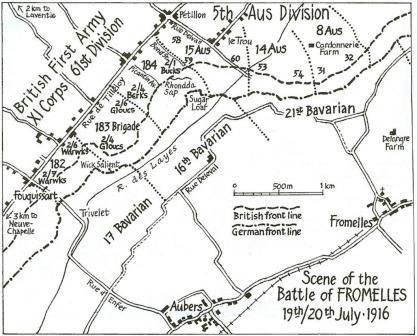

After several days of marching the 35 kilometres to Fleurbaix, the battalion was settled into billets on 16 July and by 0300 hours on the 17th they were into the front lines. Companies A and B were in the front lines with C and D companies in support.

On the 18th, they took over the trenches held by the 54th, with the communication trench running east and the trenches of the 53rd Battalion going to the River Laies on their left.

By 11:00am on the 19th, heavy bombardment was underway from both armies. At 4:00pm, the 54th Battalion re-joined on their left.

The Australian attack began at 5:43pm. There were four waves from the 53rd – half of A and B companies in each of the first two waves and half of C and D companies in the third and fourth. They initially took the German first and second line trenches, linking up with the 54th on their left, but no one could be found on the right.

The evidence of those members of the 53rd Battalion who survived the battle gives some patchy clues as to what probably happened to Clarence. These reports are taken from Clarence’s AWM Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Files with page numbers noted where relevant.

Corporal 3550 John T. James of C Company (page 14) reported that the 53rd were in the thick of the battle:

At Fleurbaix on the 19th July we were attacking at 6 p.m. We took three lines (of German trenches).

James also gave evidence about the fate of Major Victor Sampson, C Company s Commander, who was wounded very badly but was still fighting on. According to Corporal James, Victor said, Help me in boys, and I will try to throw a few bombs. Major Sampson did not survive the battle. See Sampson’s Red Cross file, page 5 [[]]

Sampson was not alone in fighting on. Clarence also fought on bravely despite injuries.

Private 2811 Arthur O. Crassingham of D Company (page 12) reported about Lieutenant Collier:

'I saw him wounded in the foot on the evening of 19/7/16 between our support and the front line trenches, and heard him tell the Sergeant to carry on

Private 2907 Henry Seemor (page 9) was fighting alongside Clarence in difficult conditions:

At Fleurbaix on 19th July Informant and (Lt C.T.) Collier were together in a charge at about 40 yards distance from our parapet. There was a muddy creek, waist deep in slush and Collier and Informant were side by side alongside this creek until a further advance was ordered. After going a few yards Collier was shot and fell. Informant saw him fall, and two days later passed the spot again and noticed that Collier’s body was still there.

Corporal James (page 14) further reported:

We were put out next morning at daylight and retired to our own line which we held. I was wounded in the German 2nd line and was making my way to the Dressing Station. Between our first line and the German 1st line I saw Lieut. Collier in a shell hole. He was wounded in the right arm. I bandaged it as best I could, and asked him to come along with me. He said I cant, at the same time he told me that he had no other wounds. I could not help him as I was wounded in the leg, and all I could do to get along myself. I was told later that our stretcher bearers could not get over the ground before our retirement, and no wounded were brought in.

By 9:00am on 20 July, the 53rd Battalion received orders to retreat from positions won and within half an hour they had ‘retired with very heavy loss’. Of the 984 men who had left Alexandria just weeks ago, 372 were killed or missing and 335 were wounded.

By 4:30pm the remains of the Brigade assembled at HQ. Clarence was not amongst them.

Private Crassingham (page 12) further reported that:

I do not know what subsequently became of him. I passed on when he fell. Unless he moved from the position, where I last saw him, he could not be a prisoner.. The bombardment was terrific, and it was easily possible for him to be blown to bits after he was wounded.

Terrible Uncertainty for the Family

With all the chaos of the battle, confirmation of the fate of the missing soldiers was a long and difficult process. ‘Wounded / Missing in Action’ was about as much as the Army could initially offer when the family was advised on 1 August 1916.

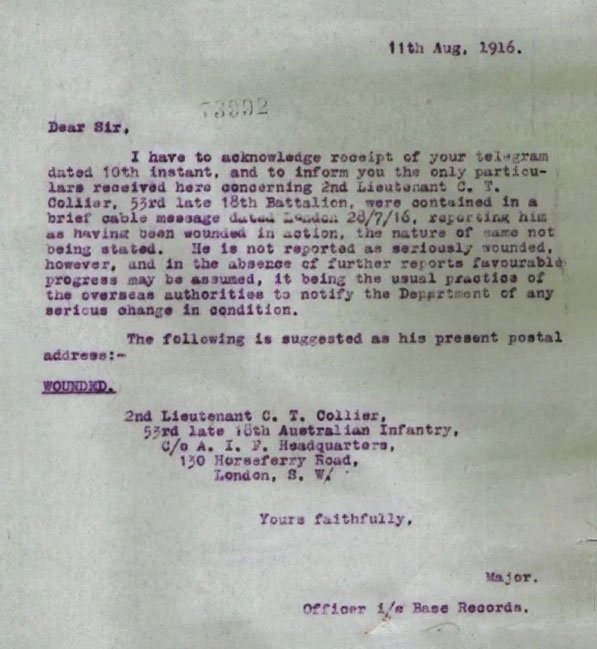

Clarence’s father, Thomas, sent a telex on 10 August and received a highly encouraging reply that his son was “not reported as seriously wounded”.

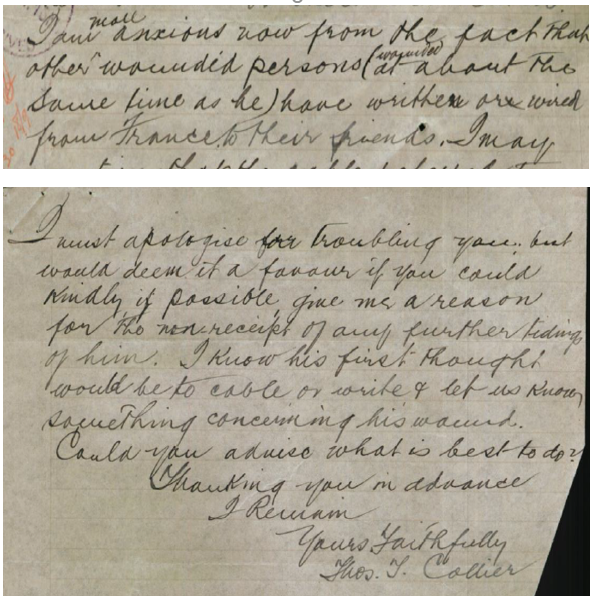

No further news was passed on, however, so Thomas, recontacted the Army on 16 September, noting that he would have expected some form of communication from or about a wounded soldier by this time.

The prompt reply on 20 September 1916 did not provide any further insights, but noted that they were dependent on information flowing back from Europe. Clarence’s girlfriend, Lyall McCoy was also in contact with the Army in early October and received the same reply.

By early November, the family was distraught with the ongoing non-response from the Army and contacted Senator Pearce, the Minister for Defence, but the reply was the same – “no further information.”

Family members have reported that Clarence’s sisters spent their time looking at every soldier's face back on the streets of Sydney, just in case.

By late February 1917, the family had managed to personally contact Private Henry Seemor (as noted above) who had returned to Sydney for treatment after being seriously wounded at Fromelles. Henry gave them the advice that he had passed on to the Red Cross that Clarence had, in fact, been killed.

The Army acknowledged that they still had not received any further information, but that they would take the advice from Private Seemor and see what could be done.

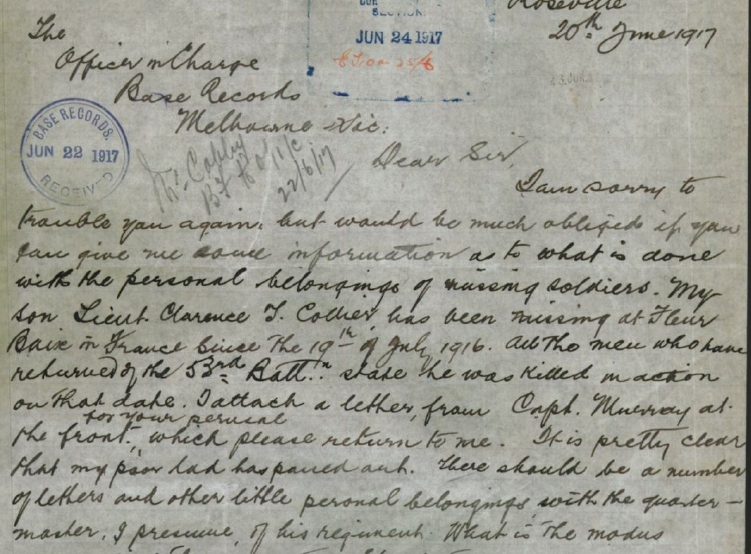

By 20 June 1917, almost a year after the battle, Clarence was still officially ‘missing’. The family had made more personal contacts, who confirmed Clarence’s death. It appears the family has accepted his death and were now seeking the return of Clarence’s belongings.

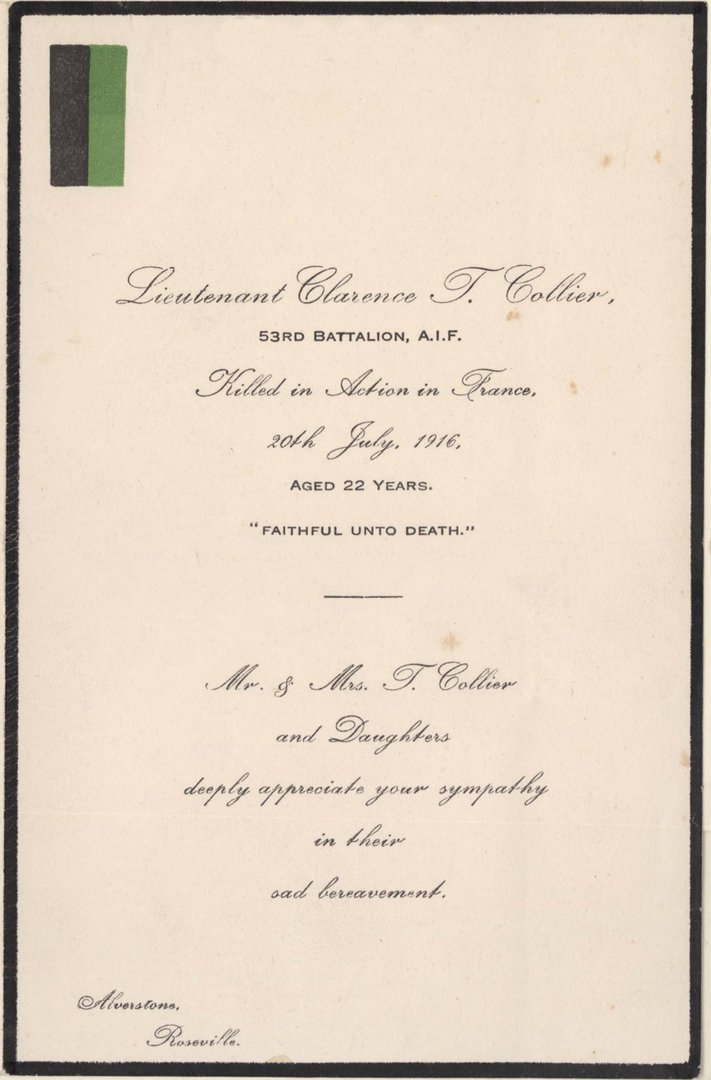

It was not until the official Court of Enquiry held “in the field” in September 1917 that Clarence was acknowledged as “Killed in Action”. It took until 1918 before Clarence’s personal effects were returned to his family.

Remembering Clarence T Collier

For his service, Clarence was awarded the British War Medal, the 1914-15 Star and the Victory Medal, all of which were issued to his father, Thomas, as next of kin. The family were also awarded the memorial plaque and scroll that was given to the families of all soldiers killed during the war. The memorial plaque was commonly known as “the dead man’s penny”.

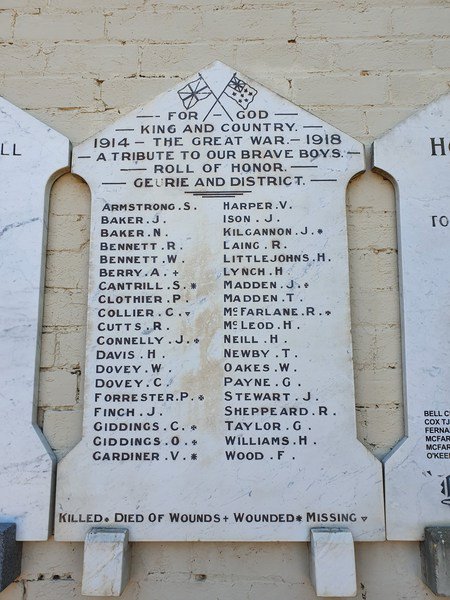

Lieutenant Clarence Collier is also commemorated on:

- panel 6 at V.C. Corner in the Australian Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles, France

- panel 156 of the Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour

- the Guerie Memorial Hall, Guerie, New South Wales

- The Roseville Roll of Honour, New South Wales.

In more recent times, on the evening of 19 July 2016, the centenary of the Battle of Fromelles, Clarence Collier’s name was included on the Law Society of New South Wales Roll of Honour. In unveiling the Roll of Honour, the society was seeking to acknowledge “the impact of WWI on NSW Judiciary" and "the important role played by solicitors in the First World War".

Closure

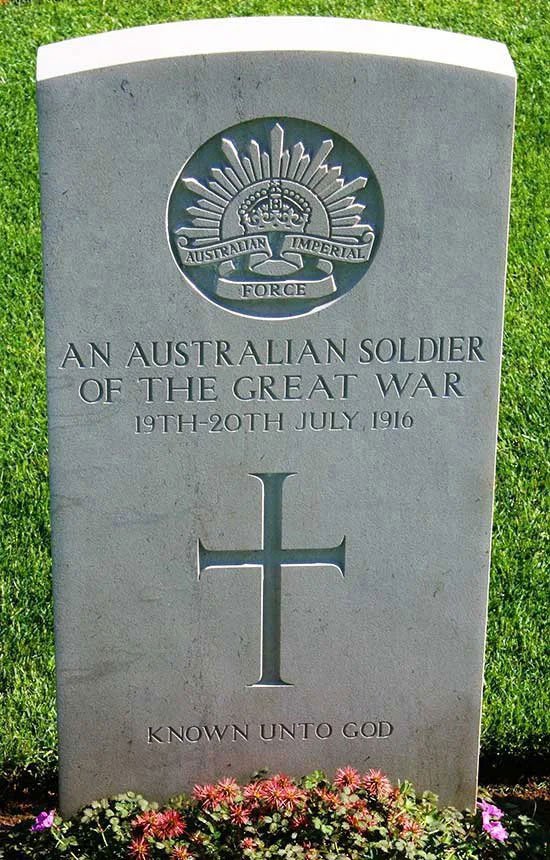

As we now know, for the soldiers who lost their lives in Fleurbaix, as Fromelles was commonly called, it was not until 2008 that the mass graves dug by the Germans that contained the remains of the Australian solders from this battle were discovered.

The story of finally achieving some closure for the Collier family was captured in a 2011 newspaper article, excerpts of which appear below.

The Daily Liberal, 21 April 2011 by Kate Cowling:

“although his body hasn’t been formally identified yet, his great-nephew David Ward said it’s only a matter of time.”

‘Clarence’s story has haunted our family for almost 100 years,’ Mr Ward, a Charles Sturt University lecturer from Cudal, said.

‘My great grandparents (Clarence’s sister and brother-in-law) used to experience a jolt of hope every time they walked down the street and saw someone of similar height and stance… Sadly they went to their graves not knowing what had happened.’”

“Tracing Clarence’s relatives proved to be difficult at first, as Clarence had four sisters and no brothers, which meant the Collier name died the day he did.

However, Red Cross letters written by Mr Ward’s great aunt, Marrianne Dakin, allowed scientists to track the ancestral lines and make the crucial connection back to Sydney.

Mrs Dakin received a phone call a few years ago with the news and was reportedly ‘beside herself’.

Along with Mr Ward and his mother, she boarded a plane to France to attend a special memorial ceremony and give Clarence the burial he deserved. Close to 1000 relatives turned out for the military service, in which each of the previously missing soldiers were reburied.

‘It was a privilege to attend,’ Mr Ward said.

‘I had never been able to visualise the impact these lost souls had on families until I stood there and saw them grieving in Fromelles.’

About 100 of the 250 bodies have now been formally identified, but Clarence isn’t one of them.”

“For Mr Ward, the discovery has more personal sentimental significance.

‘It’s closure, it’s clarity and it’s pride,’ he said.

‘It’s like we’ve finally been able to complete the circle of our family story. When he’s identified, the circle will be closed.’ ”

Note, as of late 2020, a positive match for Clarence’s DNA had been attempted but identification has not been able to be made. Clarence remains ‘Known unto God’.

Epilogue

According to advice from his family members, there had been personal letters telling his sisters to look after his girlfriend, Lyall McCoy. She and the family remained firm friends for life, even attending/assisting with her later wedding - to a German national, no less!