The Lead up to the Battle of Fromelles

The attack on Fromelles from 19 July 1916 to 20th July 1916 was the first major battle fought by Australian troops on the Western Front.

The village of Fromelles was captured in 1914 by the Germans during the Race to the Sea. Fromelles had remained in German hands ever since, nestled behind a long and well-entrenched front line, held in this sector by the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division.

The Allied aim for the battle that was about to begin was to deceive German high command into keeping their reserves in place, rather than sending them south to reinforce their units on the Somme, where the mighty Allied offensive was taking place. Preparations for the attack were rushed, the troops involved lacked experience in trench warfare and the power of the German defence was significantly underestimated, the attackers being outnumbered 2:1.

In the lead up to the attack, critical decisions were made that led to Australia having 5,533 casualties in one night, the worst 24 hours in Australia’s military history. Around 1900 soldiers were to lose their life and many remain in unmarked graves to this day, of the remaining 3500 who were wounded, they either returned to the war or were repatriated home.

This summary of the lead up to the Battle of Fromelles has kindly been supplied from Geoffrey Benns' Fromelles: 100 Years of Myths and Lies, Published 18 Aug 2021 with additional notes from C.E.W. Bean, The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1916: the official history of Australia in the war of 1914–1918, vol. 3, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1941, chapter 12 and chapter 13

5th July 1916

Prospects of a break-through on the Somme appeared to Commander in Chief Sir Douglas Haig so promising that he ordered the other armies to prepare attacks in case the enemy was thoroughly beaten there. In that event the Third Army, on the northern flank of the battle, would launch an offensive.

He neither prescribed there be a feint, or an attack, but these few lines in the hands of various generals in due course gave rise to the Battle of Fromelles. Haig ordered the First and Second Armies to select a front on which to attempt to make a break in the enemy’s lines in the following terms:

"The First and Second Armies should each select a front on which to attempt to make a break in the enemy lines, and to widen it subsequently."

7th July 1916

On 7 July, Lieutenant General Sir Alexander Godley, Commander of the II Anzac Corps told Major General Sir James McCay, commander of the 5th Division ‘that raids and all possible offensive (sic) should be undertaken at once’. General Godley issued to the II Anzac Corps – of which the 4th Division was heading for the Somme, and comprised only the New Zealand and 5th Australian Divisions – the following order:

"Raids must therefore take place immediately, and must be on a larger scale than has hitherto been attempted – about 200 men or a company"

8th July 1916

The 4th Division, less its artillery, was ordered to follow the 1st and 2nd to the Somme and the 5th Division prepared to relieve it. General Monro, at a conference of his corps, directed Haking to draw up plans involving the First and Second Armies.

Sir Douglas Haig received information that the Germans had transferred to that front from the Lille... The general staff, now looking into the several operations recently suggested, concluded that:

"the attack on Aubers-Fromelles, undertaken as “an artillery demonstration,” would “form a useful diversion and help the southern operations.”

That very day, when Haking was instructed to draw up his plan, the 4th Australian Division had been suddenly ordered to follow the rest of the 1 ANZAC Corps to the Somme. The 5th Division, ordered up to relieve the 4th, began on the same day, its first march towards the front area.

9th July 1916

On 9 July, Haking outlined a scheme for an attack by three divisions on a 4,600 yard frontage against Aubers Ridge:

‘to include the two main tactical localities on the ridge, the high ground around Fromelles and the village of Aubers’.

General Sir Charles Monro felt that a thrust from Loos held better prospects in the event of a Somme success. He turned Haking down.

On that same day, the 2/5 Warwicks attacked in daylight. Bean wrote, outlining the effect that various raids had on German forces from 9 July, 1916 onwards:

"Raiding was therefore at this time no easy process. Moreover, it is difficult to see how it could cause any serious anxiety to the enemy, and German accounts now available make it quite evident that it did not".

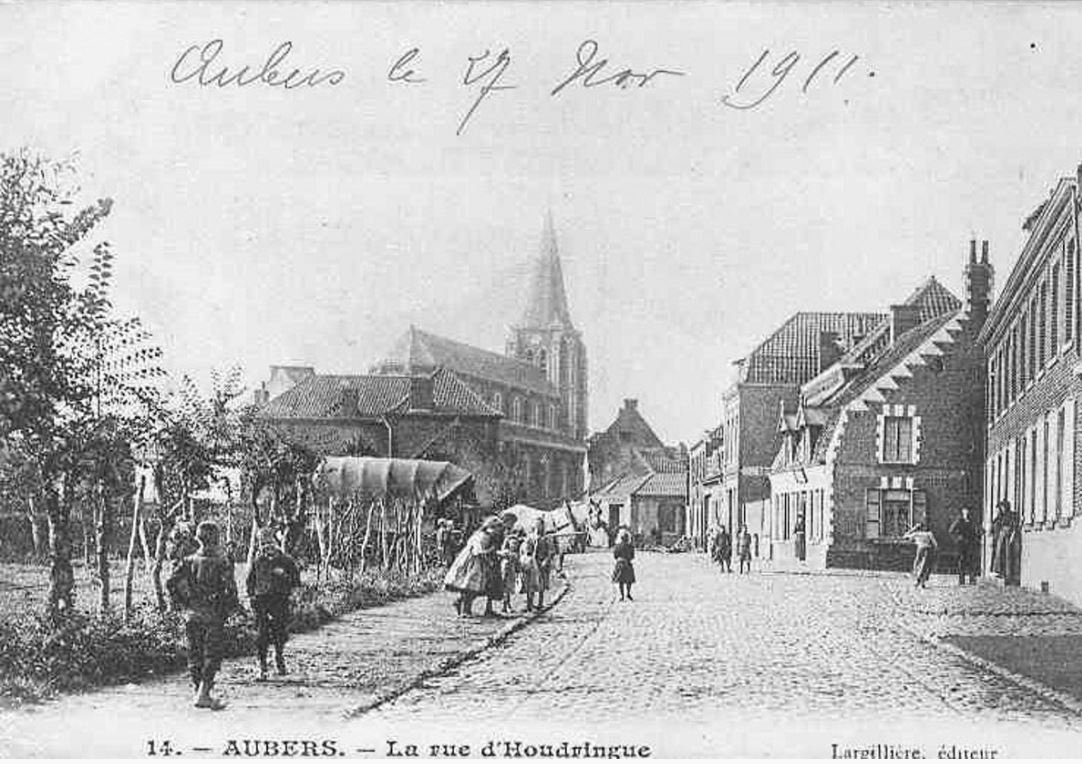

Postcard depicting rural life from Fromelles pre War

Postcard from the town of Mont Des Cats featuring the Abbey

10th July 1916

July 10, orders were given to pack up and be ready to move off at a moment's notice. No move was made till 7.15 p.m., when the battalion was moved off to the north past Le Coq de Paille to Mont des Cats, where the troops bivouaced for the night. It was fine weather and it was no hardship to sleep out among the fields and trees that beautiful summer night.

11th July 1916

At 5.50 a.m. on 11 July, the Germans blew a mine in a tit-for-tat response to one the Australian tunnellers had exploded under them a week before.

12th July 1916

General McCay at noon on July 12th in Sailly chateau took over from General Cox the command of the sector.

His division, though last of the AIF to arrive in France, would be the first in serious action. Haking’s plan as then explained to him, was to seize 6,000 yards of German front line – from the Fauquissart – Trivelet road to a point opposite the Boutillerie – with three divisions: the 61st and 31st of Haking’s own corps, would assault the south-western and northern fronts of the Sugar-loaf; the 5th Australian Division would extend the front of attack as far as Boutillerie.

That day, a Stokes mortar fired without warning near D Company, 2/4 Ox and Bucks. Replying instantly, the Germans cleaned up the entire platoon.

Source: Bean p.335

The 5th Division arrived in Armentieres.

A Soldiers Story

(1893-1916)

12th July 1916 France

Dear Mother,

Just a line to let you know I’m OK. We have shifted again nearer the firing. First we shifted to about 8 miles from the firing line to a billet where we stopped for 2 days until now. We have moved into another billet only a mile or so from the firing line. We are in houses in a village which presents a very dilapidated appearance, only a few have windows intact and many have holes in the roof, slates off, etc. We moved into this place late at night with guns going off and flares lighting up the trenches in front. We arrived alright, no-one being hurt. Along the road we passed one of our big guns. They were putting it into the square heads. You could see the flash and feel the concussion.

Your affectionate Son, Alex

Alexander wrote to his mother a few days before he was to lose his life, you can read his soldier story here

13th July 1916

Haig was informed that eight German battalions had followed 13 Jager to the Somme from the Lille area. As the raiding programme had failed to stop them, stronger action was necessary, especially with the second great attack on the Somme about to begin. You can easily conclude that if a raiding programme was seen as having failed to stop the Germans, that attacks, and indeed Battles would be needed.

But at a conference held on the 13th July, these alternative plans seem to have got mixed, and a wretched, hybrid scheme, which might well be termed a ‘tactical abortion,’ emerged from the Council of War.

Brig. Gen. Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliott of the 15th Brigade, 5th Division AIF had deep misgivings about the plan.

"At this stage it is just to mention that I had all along had the gravest misgiving as to this attack. When I moved into the line I had carefully reconnoitred it from every point of view. It had been the scene of an attack early in the war (viz., 9th May, 1915) by some 30,000 (three divisions) of Regular British troops with 25,000 more in reserve, supported by 500 guns who fired 80,000 rounds of ammunition. They suffered 10,000 casualties, and did not gain a single yard, and the attack was abandoned at nightfall on the ground that the continuance of the attack would mean a useless waste of life. Moreover, General Haking had a little farther south on the 29th June, 1916, carried out a similar attack, which was repulsed with heavy loss."

14th July 1916

At 2.00 a.m. on 14th July, Haking learned that the artillery he was receiving was not the amount he was expecting. The ammunition allocation was slashed by a third to 215,000 shells and he could only rely on the newly trained Australians.

He immediately scaled down the operation and narrowed his front of attack to 4,000 yards, and to attack with two divisions, the 61st UK Division striking at the Sugar-loaf, as already arranged, from the west, and the 5th Australian Division (instead of the 31st Division) from the north.

On the morning of 14th, McCay learned of the change in the plans. The bombardment was to begin on 14 July with all the artillery then available, and was to last about three days. General Haking’s scheme of attack was therefore approved, its object (according to the First Army order issued on 15 July) being:

“to prevent the enemy from moving troops southwards to take part in the main battle. For this purpose (it was added) the preliminary operations, so far as is possible, will give the impression of an impending offensive operation on a large scale, and the bombardment which commenced on the morning of the 14th inst. will be continued with increasing intensity up till the moment of the assault.”

The Germans were of course, watching this all unfold. High up in trees in look-outs, the enemy could watch the movements of the 5th Division situated near Fleurbaix, preparing for the attack of 19 July 1916 at Fromelles. According to intelligence obtained in Germany after the Armistice in 1918, the Germans had ample warning of the attack.

A Soldiers Story - Major Roy Harrison

Having survived Gallipoli, Roy Harrison had a more somber approach to the battle ahead. Writing to his fiancé Emily:

“By the time this reaches you, the result will be known to you through the paper, so, failing any bad news, you may take it that all is well… It is no use worrying as I am quite satisfied that what is to be, will be, and nothing can alter it for good or evil… The men don’t know yet what is before them, but some suspect that there is something in the wind. It is a most pitiful thing to see them all, going about, happy and ignorant of the fact, that a matter of hours will see many of them dead; but as the French say ‘C’est la guerre’.” (Thats War)

You can read Roys Soldier Story here

15th July 1916

Hakings plans were approved, but there may still have been reservations. Sir Douglas Haig, before whom the report was laid, noted at its foot:

"Approved, except that infantry should not be sent in unless an adequate supply of guns and ammunition for counter-battery work is provided. This depends on what guns enemy shows. " D.H. 15 July, ’16.

The plan was in place for the operation to commence on the 17th July.

Bombardments continued throughout the day and night and German troops conducted a raid late into the night with the objective of capturing prisoners.

The Germans thus learned that the 5th Australian Division was in front of them and had been there three days. The German report on the raid said they got no indication of a forthcoming attack either from their excursion into the allied trenches or from their prisoners, however they continued to prepare for an attack.

A Soldiers Story

His death occurred in the lead-up to the notorious battle of Fromelles, the worst 24 hours in Australian history, when there were 5533 Australian casualties in one night. That battle actually started on the 19th, but four days earlier the Germans launched a major raid supported by a severe bombardment, which caused 160 casualties in the 58th Battalion . . . amongst them George, who was blown to bits by a direct hit. George was very much a battalion favourite — so much so that his many admirers decided to gather what was left of him to get him properly buried . . . and they collected his remains in a blanket. He was buried nearby, in the cemetery at Rue Petillon.”

George Challis was killed in action in the lead up to the Battle, you can read his soldier story here.

16th July 1916

At a conference in Chocques on the day, General Butler pointed out that Haig did not wish the infantry to attack at all unless the commanders were satisfied they had sufficient artillery and ammunition not only to capture, but to hold and consolidate, the enemy’s trenches. A report of the conference states that General Haking:

"was most emphatic that he was quite satisfied with the resources at his disposal; he was quite confident of the success of the operation; and considered that the ammunition at his disposal was ample to put the infantry in and keep them there. "

Haking’s Memo on 16 July, 1916 was addressed to: 31st Divn, 39th Dvn, to 51st Divn, and to 5th Australian Divn, in the following terms:

"It has been ascertained that the enemy is moving his troops from our front to resist the attacks of our comrades to the south. The Commander-in-Chief has directed the XIth Corps to attack the enemy in front of us, capture his front system of trenches, and thus prevent him from reinforcing his troops to the South...."

"The objective will be strictly limited to the enemy’s support trenches and no more.”

C. E. W. Bean reports that General Haking, in a letter read to all troops on 16 July, the eve of the day appointed for the assault (it was later deferred 3 days) explained, firstly, the reason for the operation, and then the methods.

Heavy rain fell in the afternoon, so heavy that the artillery “heavies” were unable to be fired to register.

Soldiers Perspectives

Private Downie Dodd No 4770 wrote to his parents on 16th July, you can read his story here

No 4770 Pt D. Dodd 16th July 1916

Dear Father & Mother

Just a very few lines. We had our first experience of trench warfare. We were in the front line trenches for three days and were relieved two days ago. Things were a bit quiet, they say, as evidently we were sent into that part to get our schooling. Matters were pretty lively at night with snipers and machine guns going and an occasional big gun. Several shells landed in our part of the trenches but our company came out without suffering any casualties.

There is some big movement in contemplation and we are all being held in readiness. I am keeping very fit. Hope you are all in good health at home. Remember me to Bob, Alexa and the children, with love to you all,

Your affectionate son,

Downie

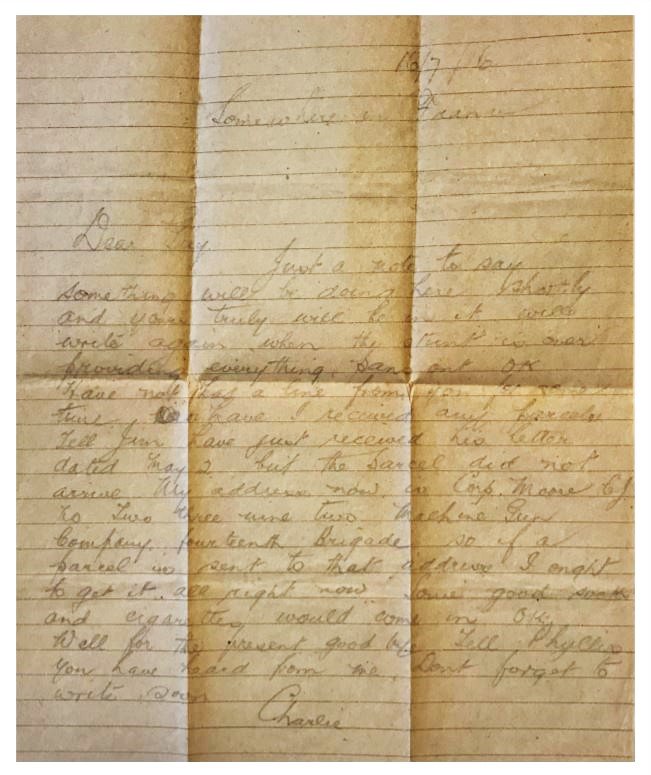

On 16 July 1916, Charles Moore wrote his letter ‘Somewhere in France’, he explained that it was:

‘Just a note to say something will be doing here shortly and yours truly will be in it. Will write again when the stunt is over, providing everything pans out OK.’

You can Read Charles Soldier Story here

The realities of war on the western front was very quickly setting in for the soldiers. Mostly billeted in farm house or towns close to the front, their mail or parcels were often missing or did not arrive at all. For Charlie, this would be his final letter home, he letter simply ends, "don't forget to write soon, Charlie."

17th July 1916

At 4.00am on the 17th, the time when the final seven hours’ bombardment should have started, a heavy mist lay upon the country. The hour was accordingly put off, first until 8.00am, and then till 11.00am. At 8.30 a.m., as the air was still too misty, Haking wrote to the First Army Commander advising with great reluctance that the operation should be postponed.

News of the postponement was received with intense relief by both divisions, whose men were well-nigh worn out with the hurried preparation. The army commander decided that the assault should not be undertaken for at least two days.

18th July 1916

The 18th was a day of both preparation and rest.

For the 32nd Battalion this meant, B & D Companies returned to the trenches to begin work on cutting passages through the Australians’ barbed wire defenses in preparation for the upcoming attack. On the 18th, A & C Companies relieved them.

The 53rd relieved the the 54th battalion who returned to their billets in Bac St. Maur. This unexpected rest was welcomed by the troops after the gruelling work of moving large supplies of ammunition and other stores needed for the now postponed attack.

While training and on rest, soldiers were often placed in billets; temporary lodgings provided to soldiers by the AIF when they were stationed behind the front lines. The troops were accommodated in a range of civilian buildings that had been acquired for military use. They were often farmhouses, but the ranks also slept in barns, halls, or whatever accommodation was available. The next day the Battle commenced.

Brigadier General "Pompey" Elliott's misgivings about the battle to come are about to be realised.

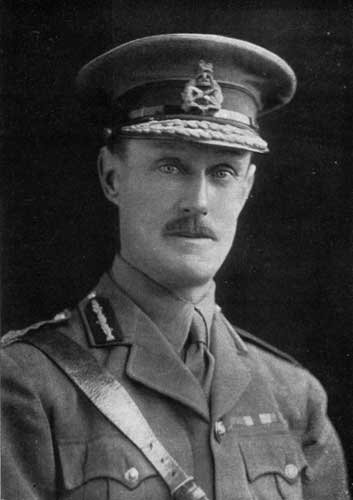

The Leadership

Commander in Chief – General Sir Douglas Haig

GOC First British Army – Sir Charles Monro

GOC XI Corps – Sir Richard Haking

GOC II ANZAC Corps – General Sir Alexander Godley

5th Australian Division GOC – Major General James McCay

8th Brigade - General Edwin Tivey (Made up of 29th, 30th, 31st and 32nd Battalions)

14th Brigade – Brigadier General Harold Pope (Made up of 53rd, 54th, 55th, 56th Battalions)

15th Brigade – General Harold Elliott (Made up of 57th, 58th, 59th, 60th Battalions)