The 19th July 1916

"Yesterday evening, south of Armentieres, we carried out some important raids on a front of two miles in which Australian troops took part. About 140 German prisoners were captured."

With those fateful words, the Battle of Fromelles was recorded.

The attack on Fromelles from 19 July 1916 to 20th July 1916 was the first major battle fought by Australian troops on the Western Front. When the troops of the 5th Australian and 61st British Divisions attacked just before 6 pm on 19 July 1916, they suffered heavily at the hands of German machine-gunners.

By 8am on 20 July 1916, the battle was over. The 5th Australian Division suffered 5,533 casualties, rendering it incapable of offensive action for many months; the 61st British Division suffered 1,547. The German casualties were little more than 1,000. The worst 24 hours to date in Australia’s military history had taken place.

This summary of the Battle of Fromelles has kindly been supplied from Geoffrey Benn's Fromelles: 100 Years of Myths and Lies, Published 18 Aug 2021 with additional notes from C.E.W. Bean, The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1916: the official history of Australia in the war of 1914–1918, vol. 3, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1941, chapter 12 and chapter 13 and extracts from Soldiers Stories.

19th July 1916

Cairo, Egypt - 31 March 1916

Timeline of the 54th Battalion, A Company

At 8.00am, The 54th Battalion paraded before their commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Cass, who informed them that they were heading back to the trenches and that the attack would go ahead that same afternoon. At 1pm, they left their billets and proceeded to the front about five kilometres away. At 3pm, Zacher’s A Company arrived in position at the front line, having moved through the 300-yard staging line and onwards via Brompton Road. Artillery from both sides began making its presence felt with increasing destruction being inflicted by the German guns exacerbated by some of the Australian artillery fire falling short and landing amongst their own troops. At 5.50pm, A Company, 54th Battalion attacked across No Man’s Land.

Extract from Henry "Zacher" Brandon's soldier story

The Bombardment Commences

11.00am

The main bombardment was to begin at midnight on 17/18 July and run for seven hours, but rain forced a postponement.

The bombardment finally began when the mist cleared at 11 o’clock in the morning of Wednesday, 19 July, with the infantry attack re-scheduled to 6 pm, instead of 11.00 am as originally planned.

As the bombardment begins, the quiet landscape is transformed into a deafening, shuddering tumult. Machine Gun Sergeant Les Martin, recalled later in a letter to his brother:

'From about 11 a.m. till 6 pm there was not a space of a second's duration when some of our guns were not firing, the row was deafening. I put wadding in my ears while we were down in the supports waiting to go forward’.

11.30am

Half an hour into the bombardment 5 British aircraft fly over the Wick Salient area to observe the effects of the shelling on the German positions. They report many German shelters and dugouts appear buried and wire defences cut.

12.00 pm

At midday, the bombardment increases. German commanders send up two aircraft to locate the British artillery positions.

1.00pm

Two hours after the Allied bombardment began, German artillery is responding. The German 32nd Battalion's commanding officer reports:

"Hostile trench mortars and 18-pounders [are] smashing our parapets and trenches to pieces. [There are] Many casualties"

2.00pm

In response to the bombardment that commenced at 11 o’clock, the enemy’s artillery began to answer the increasing British bombardment by shelling the communication trenches and reserve and support lines of both the attacking divisions. In the Australian area the ammunition and bomb-dump of the 31st Battalion was blown up and the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Toll, and most of his signallers, messengers, and the medical staff of the battalion were wounded.

"Lt. Colonel Toll displayed great gallantry all through the operations of 19/20th July 1916, at Petillon. He was slightly wounded at the commencement of the action and before the assault was made and he lost heavily in Officers and men. He led the 3rd and 4th waves over the parapet himself. "

2.30pm

Allied artillery observers report their bombardment on one of the prime targets, the Sugarloaf salient, had been ineffective and the wire entanglements remained uncut. An order is sent to increase the barrage in order to cut the wire but the message is not received until after 5.00pm by which time it's too late to prevent the planned attack, due to start at 5.45pm.

As the troops moved into position on 19 July, they were unaware that they were being watched by German observers a mile away. The Germans heavily shelled the assembly area and communications trenches, causing hundreds of Australian and British casualties before the attack even started.

The Battle Commences

By 5.00pm the German artillery was pounding the Allied front line where Australian and British troops prepared for the charge. The German artillery was supported by heavy machine guns unsilenced during six hours of bombardment.

The next hour would become a perfect demonstration of what is often called 'the fog of war' as plans and orders are overtaken by the tide of battle.

But at 5.10pm, too late for the artillery to respond, Brigadier-General 'Pompey' Elliott, received a warning. The entanglements west of the Laies River, which protected the side of the Sugarloaf facing Elliott’s men, were uncut. Observers in 60 Battalion saw three intact machine gun emplacements there. Adding to Elliott's problems, part of his force was not in position because of the ferocity of the German artillery.

At 5.15pm, to the right of the Australians, the British soldiers begin to leave doors called sally ports in the trenches and enter no-man’s-land. The effect is very different to a line of soldiers going over the parapet - the small doorways naturally funnel the soldiers, causing congestion and making them an ideal target for German machine gunners who shoot them down as they try to fan out from these narrow exits. The effect is horrific as bodies pile up around the doorways.

At 5:25pm and 5:31pm, The Australian 14th Brigade, having inadequate communication trenches, sent its third and fourth waves over the open fields between the “300 yards” and front lines . So congested are the Australian trenches that many of these men need to go out over open ground to reach their starting point. They come under intense artillery and machine gun fire as they do so.

"They came over the parapet like racehorses……… However, a man could ask nothing better, if he had to go, than to go in a charge like that, and they certainly did their job like heroes." "Allan Bennett was with us, and behaved like the gallant lad he was."

During their assault, Robert Green, Allan’s best friend from their time at Blackboy Hill, was badly wounded and fell into a shell crater. Allan, Lieutenant Sam Mills and a soldier named Bottrell ran to the aid of their fallen mate, but their retreat was cut off by a rain of artillery.

With nowhere else to go, they dragged Robert through no-man's-land towards the fighting. In their desperate dash, Allan was raked by machine gun fire. Despite his wounds, Allan managed to get himself and Robert into the unforgiving shelter of a captured enemy trench. They survived the night there, but as later reported by Sergeant Aubrey Sinclair, his condition was “very low”. This is the last known whereabouts of these two, as they were so far forward that stretcher bearers could not get through to them.

You can read Allan Bennett's Soldier Story here

The 32nd Battalion left the trenches at 5:53pm, and the 31st at 5.58pm, to attack and take the German front line. A and C Companies in 31 Battalion’s first wave went over at 5.58pm followed by its second wave on the barrage lift two minutes later. Losses were high as C Company fought hard initially but when the first wave closed with its objective, the 250 yards of breastwork, it met only a few men covering a hasty retreat.

6.00pm: British and Australian troops have in some sectors reached the German front line and are beginning to break into the trenches as Allied artillery lifts its range to target areas behind the enemy's front. The fourth wave of infantry is advancing. Two and a half hours of daylight remain.

Major Geoff McCrae, a Gallipoli veteran, leads the fourth wave of the 15th Australian Brigade, including the 59th and 60th Battalions - about 2000 men including 60 officers. His men include signallers with wire and telephones to keep headquarters informed of the battle's progress. 75 metres into no man's land, McCrae is shot in the neck and killed, as are many of the soldiers including all McCrae's signalers, who also fall dead or wounded. Messages now have to be to be carried back across no man's land by runners.

6.10pm: Private Walter 'Jimmy' Downing of 57th Battalion is watching the attack unfold:

"The 60th climbed on to the parapet, heavily laden, dragging with them scaling ladders, light bridges, picks, shovels and bags of bombs."Scores of stammering German machine-guns spluttered violently, drowning the noise of the cannonade. The air was thick with bullets, swishing in a flat lattice of death. There were gaps in the lines of men - wide ones, small ones. The survivors spread across the front, keeping the line straight... The bullets skimmed lo, from knee to groin, riddling the tumbling bodies before they touched the ground. Still the line kept on."Hundreds were mown down in the flicker of an eyelid, like great rows of teeth knocked from a comb, but still the line went on, thinning and stretching. Wounded wriggled into shell holes or were hit again. Men were cut in two by streams of bullets. And still the line went on... It was the charge of the Light Brigade once more, but more terrible, more hopeless."

It is to become one of the most poignant statements about Fromelles ever written. And a mere ten minutes have passed since 6.00 pm.

A little before 6.30pm 53rd and 54th Battalion soldiers who are now occupying the German front line from Rouges Banc to near Delangre Farm press forward in an attempt to locate the key objective, the German second line.

53rd Battalion commander Lt. Col. Ignatius Norris arrives with battalion headquarters in the fourth wave, calling

'Come on lads! Only another trench to take!'

As Norris moves forward he is cut down by an 'unsuppressed machine gun'. Norris's last words are reported to be,

'Here, I'm done, will somebody take my papers?'

With him is Private Leslie Croft, a battalion signaller, who attempts unsuccessfully, with others, to bring his wounded leader back to safety.

Others with Norris are also killed and wounded by German machine guns, including his young adjutant, 32-year-old Lieutenant Harry Moffitt.

You can read Harry Moffitt's Soldier Story here and Colonel Ignatius Norris' story here

6:45pm: The Australian and British advance is stalled and turns into a retreat under fire from their own artillery as the guns continue to hit targets behind the enemy's front line, unaware of the progress of the infantry units.

German artillery also begins to open up on no man's land, preventing other Allied units from advancing.

(1900-1916)

Joseph Davis De Pass Joseph was a soldier in the 31st Battalion. The attack was a disastrous introduction to battle for the 31st. It suffered 572 casualties - over half of its strength – many during the pre-assault phases by enemy or ‘friendly’ artillery fire and some advancing too far, lost in ‘no-man’s land’ or cut-off by the German counter-attack – a result of poor planning, maps and communication.

On the 19th July, 7p.m. [Joseph] was last seen by me about 400 yards over the German lines. He was then wounded in the foot and was crawling back towards the English lines.

Joseph was only 15 when he enlisted in 1915. All too often, those signing up new men either deliberately or were actively encouraged to overlook underage recruits.

Joseph was Killed in Action on 19 July 1916 – a boy, aged just 16 years and 1 month – the youngest Australian Jewish soldier to (enlist and) die in WW1.

The search continues for Joseph, you can read Joseph's Soldier story here

By around 7.20pm: Brigadier-General Elliott sends a report to Headquarters that the attack is failing in part because of a lack of support.

In response, Major General McCay sends about 500 men, half of the reserve 55th Battalion, into the battle.

7.45pm: On receiving word that 15 Brigade was stalled, McCay authorized Elliott at 7.45 pm to use half of his third battalion, the 58th, to reinforce the line in No man’s Land and hopefully carry it forward.

But as 8.00pm approaches, the Germans are reoccupying much of their front line. The Allied attack is failing everywhere.

Night Falls

8.00pm

Daylight begins to fade over the battlefield.

At 11th Corps headquarters, General Haking orders a fresh assault to take place in an hour's time. Having received divisional reports on the progress of the battle so far, his intention is to support the limited successes where they can be found.

Haking is under the misapprehension that the Sugarloaf salient has been dealt more damage than in fact it has. Plans are drawn up to launch an assault against it. But within half an hour these plans are cancelled as aerial reconnaissance reveals the position to still be intact.

Haking also receives news of the high number of casualties. He orders the three remaining British brigades to wait until morning before resuming the attack.

Whilst the order to delay does eventually make its way to McCay, Elliott who has been preparing his reserves to assault the Sugarloaf is never informed of the change in plan and continues to prepare for the assault.

8.13pm: Brigadier General Carter’s request for support on 184 Brigade’s left flank when the 61st renewed its attack at 9 pm reached Elliott at 8.13pm. He tasked D and C Companies of 58 Battalion to advance through 59 Battalion against the eastern face of the Sugarloaf while 184 Brigade assaulted on the western side.

8.20pm: A renewed bombardment continued as preparations were made to attack all along the front at 9.00pm. But at 8.20 pm Haking was given a first-hand report on the beating the 61st Division had taken. He directed Mackenzie to abort the 9.00 pm attack and ordered that all troops were to be withdrawn after dark.

Evidence given by 1175 Private John E. McINTOSH, D Company, 29th Battalion to the Red Cross:

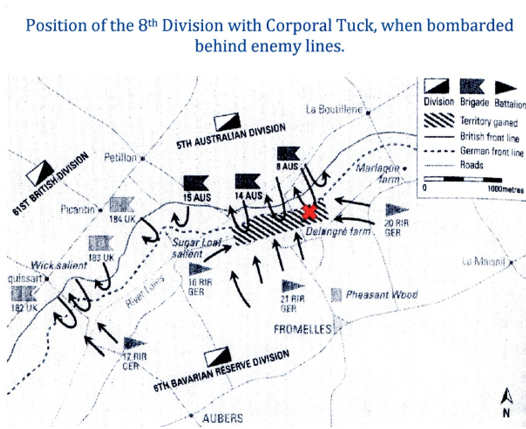

“At 9 p.m. on July 19th, the 29th Battalion holding trenches at Freomelles (sic), and attacking enemy trench about 300 yards off. The Battalion held second line enemy trenches for 11 hours. Cpl Tuck in command of No. 12 Section. Informant was told next morning by Private Grant of D. Coy, 12 Section, that during the attack a shell burst near Corporal Tuck and after the smoke and mud had cleared off, there was no sign of him, and several other men standing near him. Several men saw this besides informant.”

Corporal Alfred Tuck was part of the 29th Battalion, you can read his soldier story here

9.00pm: Harold "Pompey" Elliott orders the Australian 15th Brigade reinforcements to advance and assault the eastern face of the Sugarloaf, with two companies of the 58th Battalion and some survivors of the 59th. They are led by 21-year-old Major Arthur Hutchinson. Rising from cover, 200 metres from the Sugarloaf, they are immediately met by machine gun fire from the emplacements ahead of them. The result is a slaughter.

Major Justin Hutchinson was a member of 58th Battalion, Pte 324 George Sydney BARNES reported the following:

“Informant states that on July 19th 1916, between 10.30 and 10.45 p.m. at Fleurbaix he saw Major Hutchison (sic) hit by a shell in the first trench, of the German lines and killed. He had just got over the trenches and Informant was 5 or 6 yards behind. Informant went over at 10 p.m. in reserve. He had been ordered to go back and get more ammunition and Major Hutchison had given the order to retire, when this occurred. The trenches were lost. Informant states Major Hutchison was his company officer; that he died game, and was a credit to the company”.

You can read Justin's Soldier Story here

(1894-1916)

8th Australian Brigade headquarters receives reports that the 32nd Battalion is under great pressure: the "front line cannot be held unless reinforcements are sent. Enemy machine gunners are creeping up... The artillery is not giving support. Sandbags required in thousands. Men bringing sandbags are being wounded in the back. Water urgently required."

Elements of the 8th and 14th Brigades were successful in capturing the German front line, however due to poor reconnaissance the second German line was not where it was thought to be but much further back. Thus, the Australians ‘dug in’ 200 meters behind the German front line

As a result, there was a mix of Battalions building an Australian line behind the German front line, but they ended up as 4 separate ‘islands of troops’ in a ‘sea’ of Germans with little communication between themselves or H.Q.

Worse still, at 10.00pm, it was reported that the Battalions of the 8th and the 14th Brigade’s had few supplies and that there was no hope of any reaching them.

At 11:40pm, the Germans counter-attacked and began to reclaim their front line. Thus, the Australians were attacked from all sides and particularly from the sides and rear, so they tried to retreat through the German front line and then back to their own lines through ‘no-man’s land’. It is reported that many men decided to stay and fight, rather than to “run the gauntlet” and be shot in the back.

As the hours headed towards midnight, the 20th July 1916 will loom as another dark day for soldiers caught up in a disastrous battle.