The 20th July 1916

The attack on Fromelles from 19 July 1916 to 20th July 1916 was the first major battle fought by Australian troops on the Western Front. When the troops of the 5th Australian and 61st British Divisions attacked just before 6 pm on 19 July 1916, they suffered heavily at the hands of German machine-gunners.

By 8am on 20 July 1916, the battle was over. The 5th Australian Division suffered 5,533 casualties, rendering it incapable of offensive action for many months; the 61st British Division suffered 1,547. The German casualties were little more than 1,000. The worst 24 hours to date in Australia’s military history had taken place.

This summary of the Battle of Fromelles has kindly been supplied from Geoffrey Benn's Fromelles: 100 Years of Myths and Lies, Published 18 Aug 2021 with additional notes from C.E.W. Bean, The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1916: the official history of Australia in the war of 1914–1918, vol. 3, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1941, chapter 12 and chapter 13 and extracts from Soldiers Stories.

12.00am - 20th July 1916

As the clock ticks over Midnight to the 20th July 1916, Australian soldiers are in trouble. The Germans are on the attack to reclaim their lost territory and the Australians are ‘dug in’ 200 meters behind the German front line

There is a mix of Battalions building an Australian line behind the German front line, but they end up as 4 separate ‘islands of troops’ in a ‘sea’ of Germans with little communication between themselves or H.Q. The 8th and 14th have little supplies and no way of reaching them. Many soldiers dig in rather then attempt to retreat back to the Australian line.

By twenty past midnight, Brigadier-General Elliott has learnt that the attack on the Sugarloaf has failed disastrously and relays the information to McCay.

A third attempt is now deemed impossible. McCay's response is to order the attack abandoned and for the survivors to withdraw to their old positions and form a defensive line against an expected German counterattack.

Meanwhile General Haking's headquarters prepare plans for another attack in daylight.

1.00am

At the front, fighting continues as different units defend their positions and others attempt to retreat.

Soldiers of the Australian 8th Brigade still occupy some German frontline trenches but come under increasing pressure from the German infantry counter-attack and artillery fire.

Over the next several hours British and Australian soldiers will be pushed back to the Allied frontline through the confusion and darkness.

The postponement failed to reach the 58th Australian Battalion, which attacked with some of the 59th Australian Battalion and was stopped in no man's land with many casualties, survivors from three battalions finding their way back after dark.

Despite reinforcements, the situation of the 14th Australian Brigade troops in the German lines became desperate as artillery fire and German counter-attacks from the open right flank, forced a slow withdrawal in the dark.

A Soldier's Perspective

No. 3038A Pte Beith W. was in B Coy 56th Bn on 19.7.16. I was his Section Commander. Early in the morning of 20.7.16 while the Bn was in action a call was made for volunteer bombers. He and I went. While bombing the enemy, the supply of bombs ran short and I was sent back with a written message………..On my return with a supply of bombs, the retirement was taking place and there were many dead lying there. I have not seen Pte Beith since.

You can read Williams Soldier Story Here

2.00am

On the left flank, more troops were sent forward with ammunition to the 8th Australian Brigade at dusk and at 2:00 a.m. every soldier who could be found was sent forward. Consolidation in the German lines was slow as the troops lacked experience, many officers were casualties and there was no dry soil to fill sandbags, mud being substituted.

(1891-1916)

A Soldiers Story - Lieutenant Mendelsohn

Lieutenanant Berrol Mendelsohn was one of 10 known Jewish soldiers who died at the Battle of Fromelles. He was commended for his bravery. He was identified and reinterred at Pheasant Wood in 2009 with a ceremony in 2010 to reveal his headstone. Sergeant Armstrong noted:

At about 2am on July 20 the Germans counter-attacked heavily and we stood to, to withstand the attack, Lt. Mendelsohn in command. At about 2:30am he was shot through the head standing alongside me, whilst urging his men on to greater effort. Death was instantaneous, I was myself wounded shortly after but have ascertained that [his] body was not removed from the trench and was probably buried by the Germans.”

You can read Berrol's Soldier Story here

3.15am

German counter-attacks on the front and flanks, with machine-gun fire from Delangre Farm, Mouquet Farm and The Tadpole, began at 3:15 a.m. on 20 July, forcing a retirement to the German first line and then a withdrawal to the original Australian front line. During the withdrawals some troops managed to fight their way out but many were cut off and captured.

4.00 am

Just before 4.00 am, orders to retreat reach elements of the 8th Brigade still holding positions on the German frontline. Whilst some units refuse to leave, remaining locked in hand to hand combat against the Germans, others make a break for the Allied line across no man's land. Many are cut down by German machine gun fire as they try to reach the Allied line.

Captain Charles Arblaster and the remnants of the 53rd Battalion positioned behind the German frontline trenches come under heavy attack from German units and contemplate retreat to their own frontline which is now dangerously far way. As Arblaster leads the retreat his men are struck by a hail of German gunfire. Captain Arblaster is shot through both arms, and falls wounded. He and other survivors make their way back to the German front line. They seek cover in the trench and are taken prisoner.

"In the early morning Captain Arblaster, in a hand-to-hand fight with the enemy, was struck down by a Fritz bomb. Captain Murray took charge of the captured position and resisted all attacks. Those who were left realised now that the struggle was hopeless, but they cared not. They looked death in the face without flinching and resolved to sell their lives dearly. Never shall I forget the scenes of carnage witnessed on that awful night."

You can read Charles Soldier Story here

5.00am

In Sailly, some 8-9 Kilometres away fromt the Battle, General Haking, McCay and Mackenzie met to plan the 61st Division’s fresh attack. Monro was also present, he was asked whether 14 Brigade should be reinforced or withdrawn. Monro opted to abandon the attack and withdraw.

Source: Pedersen p.101

A Soldiers Perspective

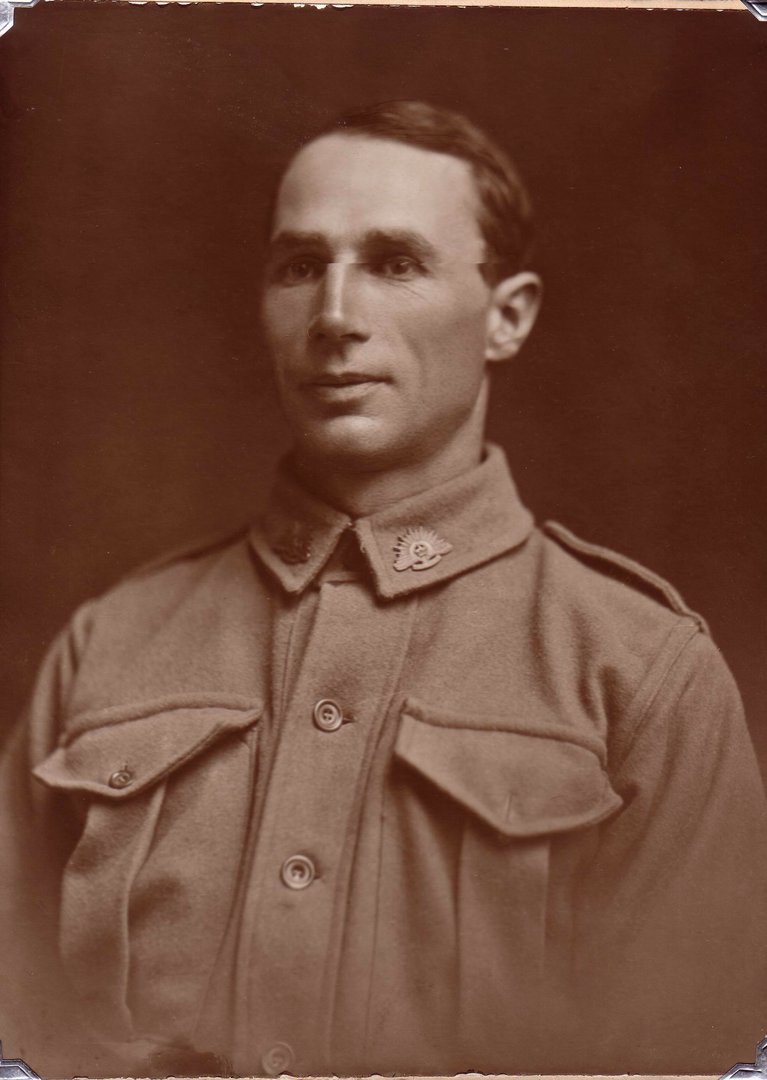

(1893-1916)

Herbert’s only child, Mary Monica Bolt, was just seven months old when he enlisted and just seventeen months old when he was killed. Sadly, she never knew much of her father as her mother never discussed him at all. The only knowledge she had was that he fought in World War 1 and was a very good Rugby League player who played for the Newtown Bluebags. He loved all sports. He was a very good boxer and excelled at Rugby League having played over fifty games between 1912 and 1915 for the legendary Newtown Bluebags, one of the founding teams of the New South Wales Rugby Football League.

"On the morning of 20.7.16, at about 5a.m., at Fleurbaix, in the communications trench near the first line of German trenches as we were retiring from the 3rd line of German trenches. He and I were close to one another, when we were attacked by the Germans. He got more than 6 of them with his bayonet and the butt of his rifle, when he got a bullet through the head. He fell instantly, being killed outright. He was as game as any man, and was a well-known Newtown footballer”.

You can read Herbert Bolts story here

5.10am

The order for a general retreat is finally given by General Charles Munro, Commander of the British First Army. But retreat is at least as perilous as attack, and many soldiers fall as they try to get back to the Allied line.

Word of the retreat does not reach all units at the same time, and soldiers are still coming back as late as 8 o'clock in the morning, a good hour after German forces have recaptured much of their original frontline positions. Pockets of soldiers, such as those from the 53rd Battalion are trapped in their forward positions, forced to surrender and become prisoners of war.

The Australian 14th Brigade is one of the last units to receive the order to withdraw, as German forces press their counter-attack. 14th Brigade commander, Lieutenant Colonel Cass' report stated that:

"these attacks caused the 53rd to break and crowd in on my right. Many of the men were demoralized and a mixed party surrendered. It would appear that at least six Germans in Australian uniforms went over to the Germans from the vicinity of the right of the 53rd and others seeing this followed."

14th Brigade's retreat is assisted by the make-shift ditches and tunnels known as saps that have been dug by fellow soldiers through the night to assist in traversing no man's land. These have even been laid with duckboards and Cass sends his machine gunners back one at a time, carefully establishing a rear guard during this orderly withdrawal.

7.00am

The withdrawal order finally reached Cass at 7.50am – eight runners were needed to get it through. He spread the word to use the communication trench across No Man’s Land. Captain Norman

German troops had got well behind the right flank and fired at every sign of movement, forcing the Australians to withdraw along the communication trench dug overnight.

Many were shot down while charging towards it. Those who succeeded could only move slowly along its congested course and the rearguard was hard pressed to keep the Germans at arm’s length while they got away.

From the comparative safety of the British frontline trench Corporal Williams observed:

"We were powerless to assist them, and had to watch them being shot down at point blank range... It seemed an eternity of time until the lucky ones reached our parapets, to be pulled in by willing hands. No sooner was our field of fire clear than we blazed into the Germans who had lined their parapets to punish the retiring troops."

8.00am

Just before 8.00am, German forces launch another attack.

14th Australian Brigade are the last men out and are ordered to hold the Germans back. Their retreat is haphazard. Some men hold their positions to the end, whilst others are sent back by their commanding officers.

9.00am

By 9:00am the remnants of the 53rd, 54th and 55th battalions had returned; many wounded were rescued but only four of the machine-guns were recovered. Artillery-fire from both sides diminished and work began on either side of no man's land to repair defences; a short truce was arranged by the Germans and Australians to recover their wounded.

9.20am

At 9.20am on the 20th July, the Bavarian 6th Division Command considers the battle won. An Intelligence Officer notes that the last of the British and Australians left defending themselves have been captured.

Casualties in the (German) 6th Bavarian Reserve Division totalled 1,582. From the German standpoint, the result was outstanding, and not just because of the highly favourable casualty ratio. Searching the dead and the prisoners, they found a copy of the general order from Haking that was read to all troops on the eve of the assault. By stating quite plainly that the objective was ‘strictly limited to the enemy’s support trenches and no more’, it told them that a feint had been intended.

The battle had cost the British 61st Division 1,547 casualties, which represented a loss rate in the assault battalions of 46 percent. As nearly all of the 5th Australian Division had been sucked in, its casualties amounted to 5,533 men, of who around 2000 perished. The loss rate in its assault battalions averaged 76 percent, while the flanking battalions suffered over 80 percent casualties. Of the 481 men taken prisoner, about 400 were Australians captured in a single battle. They were taken to Lille, marched through the suburbs and city in order to impress the French and then interrogated.

Throughout the next few days, some wounded soldiers were brought back to Australian lines, but for many they were stranded in No Mans Land.

(1882-1916)

The evidence given to the Red Cross enquiry generally agreed that Spencer Maxted was killed by shellfire. The men of the 54th Battalion attest to his expertise at bandaging and his willingness to be with the troops in the front line and to help where needed. Stories are told of him acting as stretcher bearer to move the wounded - often while under fire – providing water, giving up his own helmet to a young soldier who had lost his, and the like. Some of the soldiers characterised their padre as ‘plucky’, ‘a man among men’ and ‘a grand man’.

“In the Australian trenches the scene was such that General Tivey, who, always solicitous for his men, had hurried thither on hearing of the retirement, could not hold back his tears.

In spite of the clearance of wounded during the night by motor-ambulances working as far forward as the usual battalion headquarters, the front line was now peopled with wounded and dying, among whom Chaplain Maxted, working in his shirt-sleeves and without puttees, rendered, until he was killed, services of mercy never to be forgotten by those who benefited by them.”

You can read Chaplain Spencer Maxted's Story Here

Where the Australian wounded lay thick, the Germans began to go over their parapets, apparently in order to bring in the men lying nearest to them. A message was accordingly sent by the 15th Brigade asking the artillery to stop any of its guns which was then firing. In the meanwhile the proposal reached M’Cay. He, however, was aware that “ G.H.Q. orders and all subordinate orders were extremely definite,” to the effect that no negotiations of any kind, and on any subject, were to be had with the enemy." M'Cay ordered there be no truce. Upon M’Cay’s order reaching the front line, the stretcherbearers were stopped from going out. No shots were fired at the Sugar-loaf, where the Germans were still out among the wounded, and all artillery-fire was abated, but a desultory sniping was resumed by both sides elsewhere.

On the night of July 20th the work was organised, all battalions, including the pioneers, sending out stretcher-bearing parties, by which no less than 300 were rescued.

Source: Bean p440

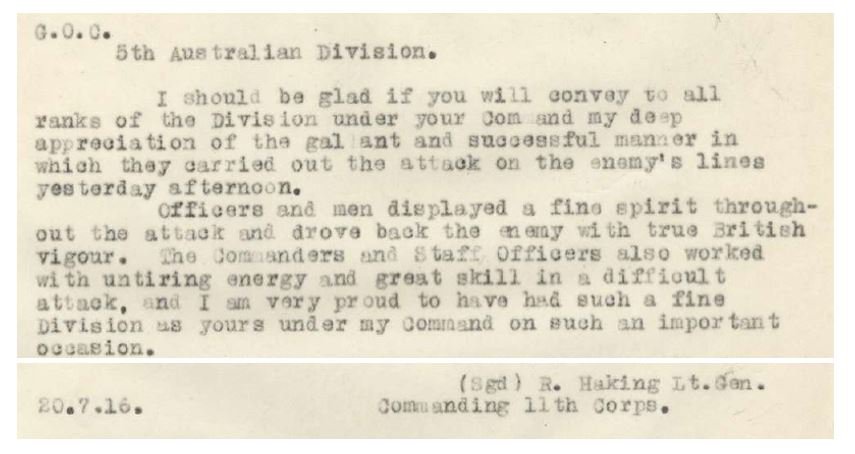

The official British communique after the fighting described the failed Battle as ‘some important raids’, evidently to conceal the severity of the disastrous reverse. Hakings words to the 5th Division are almost buoyant.

The planning process at the start was a dog’s breakfast that Bean described in one of the most famous passages in the Australian Official History:

"Suggested first by Haking as a feint-attack; then by Plumer as part of a victorious advance; rejected by Monro in favour of attack elsewhere; put forward again by G.H.Q. as a “purely artillery” demonstration; ordered as a demonstration but with an infantry operation added, according to Haking’s plan and through his emphatic advocacy; almost cancelled - through weather and the doubts of G.H.Q. – and finally reinstated by Haig, apparently as an urgent demonstration – such were the changes of form through which the plans of this ill-fated operation had successively passed."

The Battle was over, but the war was to continue.

This was the Australians first attack on European soil and its deadliest night. Countless lives of soldiers and their families were to be impacted.

For families back home of soldiers that fell, the wait would be long to find the truth of what happened, for those injured or repatriated, the scars would continue and for the soldiers who survived, haunting memories of a fateful night that took so many.