Harold John WILKIN

Eyes blue, Hair light brown, Complexion fresh

The Wilkin twins – Ernest Frank and Harold John “Always Remembered”

We are indebted to family member Kate Walker for the family story, photos and reflections.

The twins were sons of William WILKIN and Harriet Elizabeth CLARK - both of whom were born in England and came to Australia as children with their respective parents. Married in 1881 at Castlemaine on the Victorian goldfields, William was employed as a schoolteacher and headmaster in the local district.

Born 18 January 1893 at Clementson near Allendale in Victoria, the twins were Harriet's fifth pregnancy. She had already given birth to George, Amy, Reg and Irene but baby Irene died at just twelve months. A further three children arrived after the twins - William, Irene (named after the earlier baby) and Hubert (Bert).

Family member, Kate Walker, a great niece to the twins who were known to the family as Ern and Jack, shares the family story passed down to her as follows:

“My grandfather William was born 21 months after the twins and then a further sister and a brother followed him. I do not know much about their early life but believe they moved a few times as their father, William, was transferred to different schools as headmaster. Their enlistment reports their birthplace as Clementson, Victoria, a small gold mining town.

Because my grandfather left home quite young and did not make much effort to stay in touch with his family, I don’t know many of that side of the family, although my father and my aunt knew Jack and his wife Winifred and their daughter, Cousin Ruth, as they were growing up. No one really knew what had happened to Ernest and he was not mentioned at all while I was growing up.”

Enlistment of the Wilkin twins

Interested to know more about her great-uncles, Kate reviewed their military records and noted that “Ern listed 'farmer' as his occupation when he enlisted and I think Jack was some sort of a clerk. They did not enlist together - Harold John enlisting on 8 July 1915 and Ern on 18 August 1915 - but they did end up in the same company and sailed together aboard the "Ascanius" from Melbourne on 10 November 1915.

The 22-year-old twins were assigned to the newly formed 29th Battalion and both were allocated to D company. With thousands of other new recruits keen to do their bit after the horrendous losses at Gallipoli, Ern and Jack undertook training at the Broadmeadows camp before embarking for Egypt in November 1915.

Egypt

The new recruits arrived in Egypt in early December to begin training and to assist in defending the Suez Canal. There were thousands of troops pouring into Egypt from Australia in addition to the seasoned troops completing the evacuation of Gallipoli. This was to signal many months of re-organisation and intensive training for the AIF in desert conditions.

Those harsh conditions together with the crowded living conditions led to outbreaks of disease including mumps, influenza and dysentery. Ern and Jack were fortunate as they appear to have avoided these outbreaks although Ern suffered a bout with pleurisy and was hospitalised for more than two weeks in late April 1916. He returned to his unit from the hospital on 12 May.

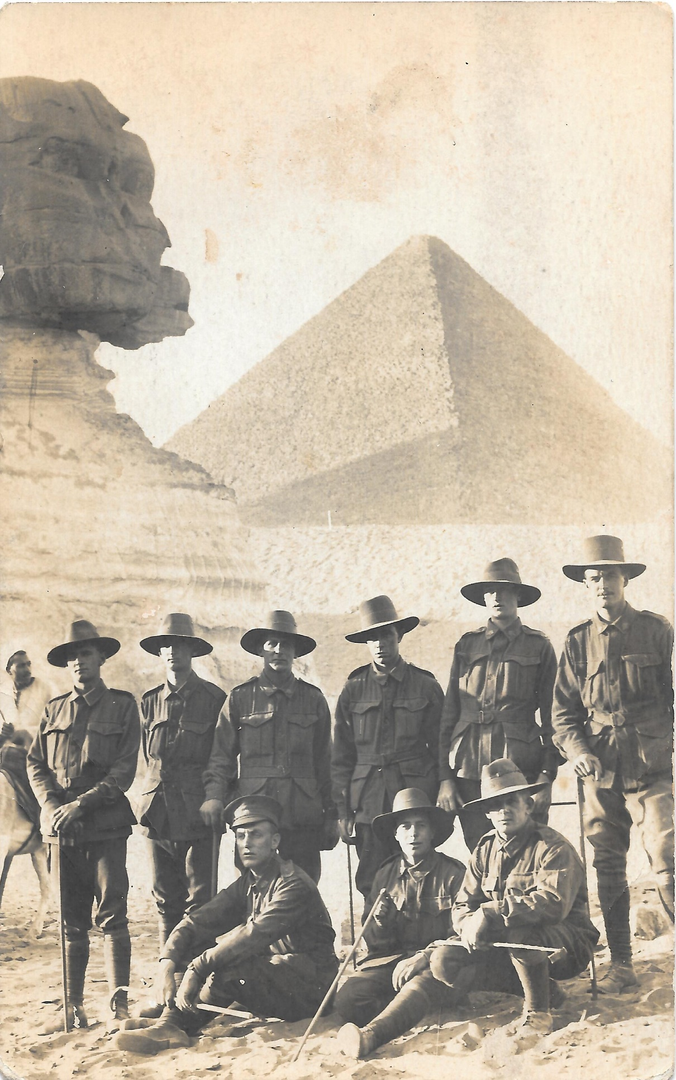

While the troops trained and worked hard, these young men also had the opportunity to explore the wonders of Egypt – an adventure for many experiencing their first travel outside of Australia. There are many photos of young soldiers riding camels or posing in front of the pyramids or the Sphinx.

The photo below is one such image of nine Australian Diggers taken on New Year’s Day 1916 in front of the Sphinx. It was sent home by Pte Clarrie Aspinall and includes nine members of the 29th Battalion’s D Company, including Ern and Jack Wilkin.

At back: 1269 Harold (Jack) WILKIN, 1314 Ernest WILKIN (not certain which is which), 1094 Edgar CHILDS, 1158 Roy KNIGHT, 1254 William TAIT, and 1056 Clarrie ASPINALL

At front: 1257 William TYERS, 1057 George BOYSE, and 1159 Alexander KAY

On 16 June 1916, the 29th Battalion left Egypt to join the British Expeditionary Force in France on the Western Front.

Battle of Fromelles, France

Arriving in Marseilles on 23 June 1916, the Australians were well received as Private James Lang (858) of Glengarry, Victoria wrote:

“The French people lined the streets to see us, and gave us a great welcome. Lots of poor woman and young girls started crying. No doubt the poor things were thinking of their own dear ones who had gone to the front.”

The 29th took the train to Hazebrouck and on to Steenbeque and by June 26th they were encamped in Morbeque, about 30 kilometres from Fleurbaix. On 1 July they moved to Hazebrouck where training included the use of gas masks for the possible use of “lachrymatory shells” – tear gas. Training was tough. One day included a march of 16 miles carrying 75 pounds of kit, which only the youngest and fittest could complete.

On July 9th, they moved to Erquingham, just outside of Fleurbaix and on the 10th they got their first experience in the frontline trenches.

They were back in Fleurbaix on the 14th and on 19 July, Ern and Jack and their comrades in D company were in the trenches by 8pm together with A company, both companies ready for the attack. Many of the men broke through the forward lines of German trenches looking for what they had been told was a second line. Instead, all they found were a series of shallow drainage ditches.

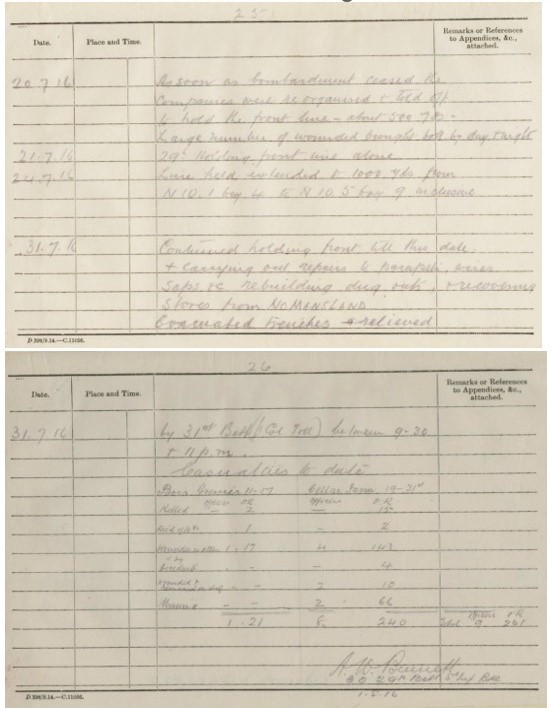

At 2 am the German counterattack began, but as noted in the Battalion’s War Diaries (AWM), “After a struggle, Germans content to stop at their own trench.”

The attack on their right was altered and D company became exposed in a salient jutting into the German lines and were quickly enfiladed by German machine guns. In the end, they basically had to fight their way back to their own lines, ‘run for it’, or be killed, wounded or captured.

As noted on the Australian War Memorial website, the nature of this battle was summed up by one soldier from the 29th, “the novelty of being a soldier wore off in about five seconds, it was like a bloody butcher’s shop”.

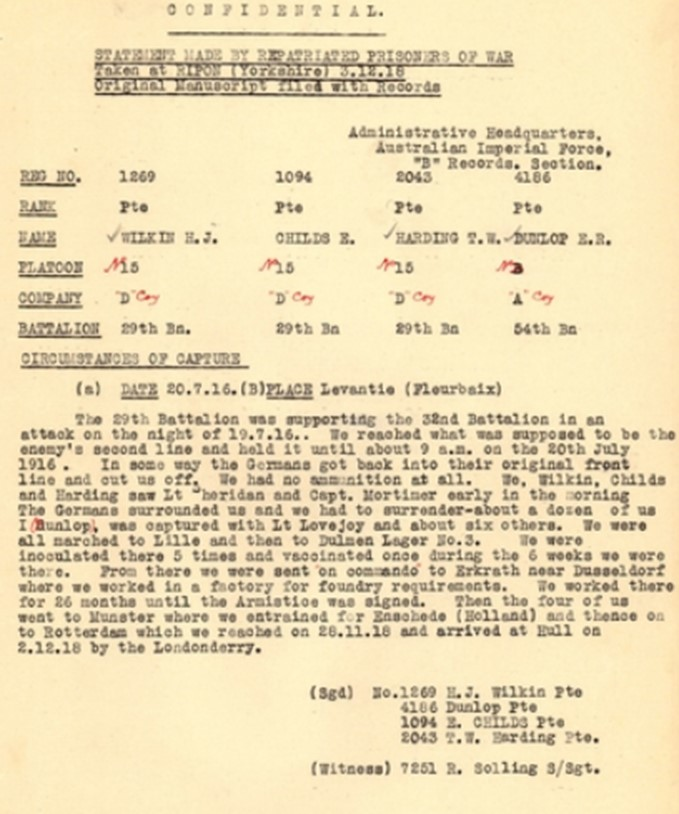

After the Battle of Fromelles, the 29th Battalion remained holding the front line for a further 10 days until they were eventually relieved by the 31st Battalion late on the evening of 31 July. The casualty list for the 29th Battalion from the Battle of Fromelles (until 31 July) is listed as 8 officers and 240 other ranks. Of that total 66 were missing, including the twins Privates Ern and Jack Wilkin. These sparse notes go some way to explain the confusion and delays in discovering the fate of so many of the men.

Missing in action – conflicting news

For the Wilkin family at home, confusion appears to have been a key element for them in learning the fates of the Ern and Jack. AIF files indicate that the family were advised in late August that both twins were missing in action between 21 and 25 July 1916 somewhere in France.

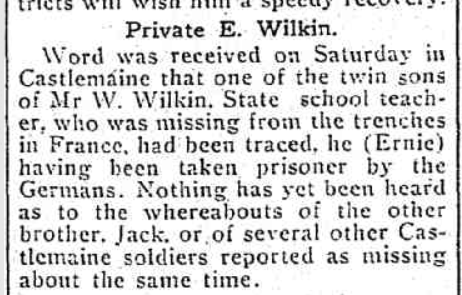

News reports in September 1916 give different stories varying from: both twins being prisoners of war; both wounded with one having lost a leg; to Ernie being a prisoner of war and no news of Jack.

From Jack’s AIF file it is recorded that the family, through his father as next of kin, was advised on about 8 September 1916 that Jack was a prisoner of war in Germany. This appears to have been an unofficial finding based on a letter sent by a fellow prisoner of war (Sergeant 1321 Oliver Stanley Cole) to the commanding officer of the 29th Battalion listing about 40 men taken prisoner after the Battle of Fromelles.

Sergeant Cole’s letter was dated 27 July 1916 but may have taken some time to reach authorities in London. At least, the Wilkin family had news of one son though Ern was still listed as missing in action with no details known.

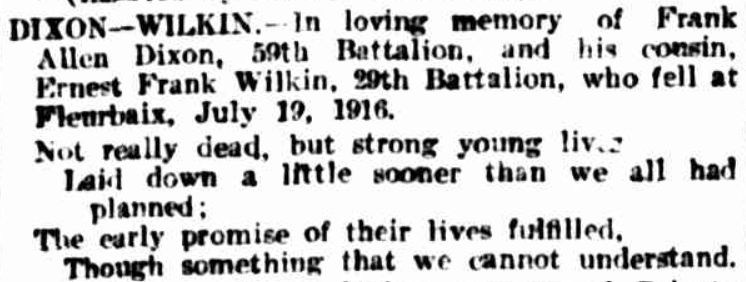

So, for the family, there was a period when they suffered the stress of either no information or of conflicting and incorrect information about their sons. It is likely that this was exacerbated as a younger first cousin of the Wilkin twins was also missing in action after the Battle of Fromelles.

Lance Sergeant 2545 Frank Allen Dixon (whose mother Kate was sister to the twins’ father, William Wilkin) had enlisted in May 1915 and was serving with the 59th Battalion. Like the twins, Frank was listed as missing in action after the battle on the night of 19-20 July 1916.

There was no news of Frank Dixon until a report was received in February 1917 that he was being held as a prisoner in Switzerland. Sadly, in May 1917 they were advised that the report was incorrect. He was still missing in action.

In September 1917, Frank’s name was published in an official casualty list as having been killed in action on 19 July 1916. On his AIF file, there is a heartbreaking letter to authorities from his mother asking, “why did we not have official word before it was published?”

Given it was a time of war and communication channels were limited, it is understandable that mistakes and confusion sometimes arose but the anguish for families can still only be imagined and for two such dreadful errors to have occurred in relation to young Frank Dixon was a cruel twist of fate.

Jack’s story

With Ern still missing, the family at least had the comfort of knowing that Jack was alive, although in German hands. The unofficial information from Sgt Cole was eventually confirmed from German sources through the Red Cross. In November 1916, Jack also wrote via the Red Cross seeking information about Ern. Like the family back home, he too was seeking word about his twin brother.

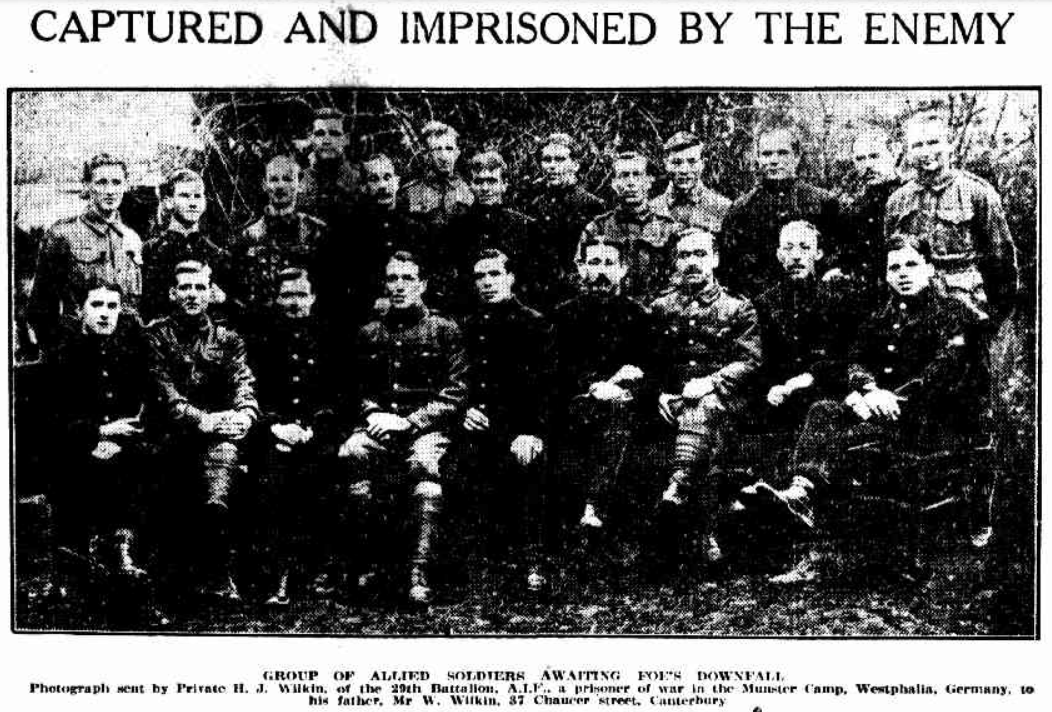

Postcards and occasional letters would have eventually made their way from Jack to family and authorities passed on information whenever they were advised that Jack had been transferred to other prisons in Germany. He was held initially at the Dulmen camp but was then moved to the Munster prison. At Dulmen, he met prisoners Pte Amey, Pte Carter and Pte Reuben Parry brother of Frederick, who was also killed in action and reportedly buried alongside Ernest. Both Harold and Reuben lost brothers at Fromelles and were taken prisoner of war during the battle.

As a prisoner of war, Jack was required to work for the Germans and many prisoners suffered ill treatment and poor living conditions. Red Cross parcels were sent but did not always reach intended recipients.

For about two years, Jack worked in a factory near Dusseldorf and it appears that throughout his time as a prisoner he was held with Pte 1094 Edgar Childs, a comrade in the 29th Battalion, D Company. Edgar had travelled with the twins on the Ascanius and he is also pictured in the group of nine in front of the Sphinx.

When the Armistice was signed, Jack and his fellow prisoners of war were repatriated to England with Jack arriving in Dover on 2 December 1918. He then spent four months recuperating at the Ripon camp in north-west Yorkshire in England.

Jack left England on 5 March 1919 aboard the SS Nevasa to return to Australia, arriving in Portsea on Anzac Day, 1919. He was discharged from the AIF in June and returned to his career as a clerk, eventually becoming a manager. He married in 1928 and had a family, dying in 1964, aged 71.

Ernie’s story

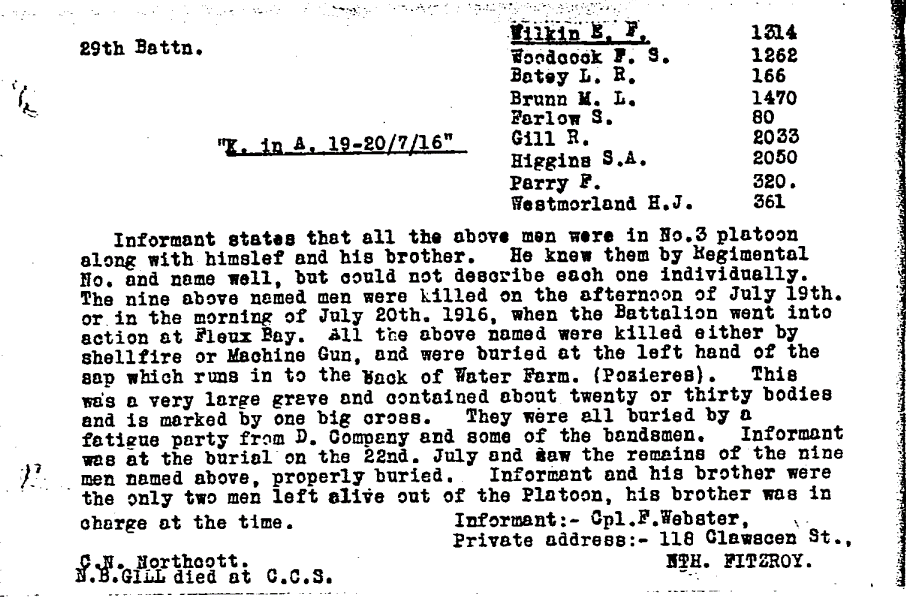

In April 1917, an official court of enquiry was finalised and found that Private Ernest Wilkin had been killed in action at Fromelles on 19 July 1916. Ern’s name had appeared in German lists of those killed at Fromelles and his identity disc was returned to British authorities but the only specific record detailing his fate is the evidence of a fellow soldier, 356 Corporal Frederick Webster.

Webster stated that Ernest was one of nine soldiers from his platoon killed during the Battle of Fromelles and buried in a sap on 22 July 1916. It seems Ern was killed by machine gun or shellfire.

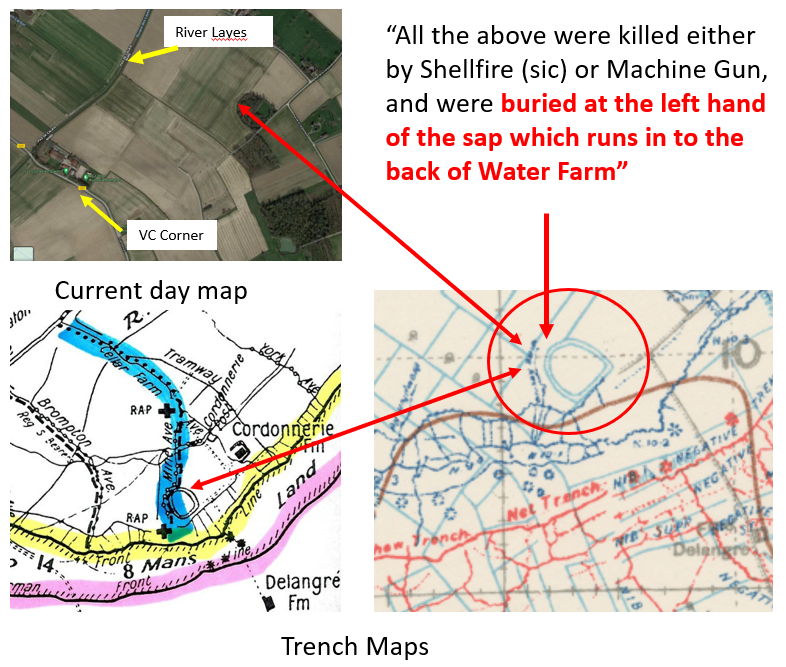

The sap (a short covered trench / tunnel) is probably on the Mine Ave end of the trench (marked in blue in the map below) near where the “water farm” is marked.

Individual soldiers mentioned in the list of nine were recovered by the German Army, buried in the mass graves and, post-2009, identified by DNA and re-interred at the Pheasant Wood cemetery at Fromelles. There are also similar notes in these soldiers’ AIF files that they are buried at Fleurbaix, and a general map reference, sheet 36, with the exception being Private Robert Gill who died at the casualty clearing station and is buried at the Bailleul Communal Cemetery Extension.

It would have been chaos in the trenches during the battle and in the immediate aftermath, and it is no wonder records of deaths and burials are often non-existent or contradictory. There are no records of these soldiers being found in this vicinity. However, in 2008 a burial ground was located at Pheasant Wood behind the old German front line at Fromelles that contained the bodies of 250 British and Australian soldiers.

Many of their identities, including Fred, were confirmed through a combination of anthropological, archaeological, historical and DNA techniques.

To date (2024), DNA testing has been able to identify 180 of these 250 soldiers.

Despite being identified as being buried in the sap, four of these nine men - Ernest Wilkin, Frederick Parry, Samuel Farlow and Norman Brumm – were identified in 2010 as being buried in the Pheasant Wood Cemetery! Was the original grave disturbed by shelling or otherwise re-opened necessitating re-burial by the Germans?

With four already identified, are the remaining four (Herbert Westmoreland, Francis Woodcock, Lemuel Batey and James Higgins) still amongst those soldiers now buried at the Pheasant Wood cemetery but unidentified?

After the official finding of the court of enquiry, the family were notified and his personal effects were returned to them in July 1917. Those personal effects included a safety razor, handkerchief, diary, pocketbook, cards, letters, fountain pen and photos. His identity disc was sent home later that same year and, after the war, Ern’s war service medals (1914-15 Star, British War Medal, Victory Medal), memorial plaque and memorial scroll were issued to his father.

With no confirmed place of burial, Ern’s name was recorded on panel 1 of the V.C. Corner Memorial at Fromelles. The name of his younger cousin, Lance Sergeant Frank Dixon 1894-1916, is on the same memorial, panel 15.

2010, a new chapter in Ern’s story

In 2010, soldiers who had been buried by the Germans in the mass grave at Fromelles were re-buried in the new Pheasant Wood Military Cemetery. At the time of the official dedication of the new cemetery, fewer than one hundred soldiers had been identified but fortunately for the Wilkin family, Private Ernest Wilkin was one of those. He now has a dedicated grave (Plot II, Row E, Grave 6) with his details honouring his service.

Kate Walker recalls her visits to Fromelles to honour her great uncle:

“I have visited Fromelles - first in 2010 after I had been in England as Leader of a group of Australian Girl Guides attending the World Centenary of Girl Guides Jamboree in Yorkshire and stopped off at Lille to visit Fromelles on my way to meet one of my daughters in Switzerland. That was something of an experience navigating myself (with almost no French!) to Fromelles by train and bus!

My husband and I were also lucky enough to be included in those who attended the Fromelles Centenary commemorations in July 2016.”.

As his headstone now reads, Private Ernest Wilkin will be “always remembered”.

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: royce@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).