Ernest William ABBOTT

Eyes blue, Hair black, Complexion fair

Ernest William Abbott – A Godly Young Fellow from Five Dock

Can you help find Ern?

Ernest William Abbott’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial. A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing. Ern may be among the remaining 70 unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in White Hill, Bendigo, Victoria. See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family. If you know anything of contacts for Ern, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Early Life

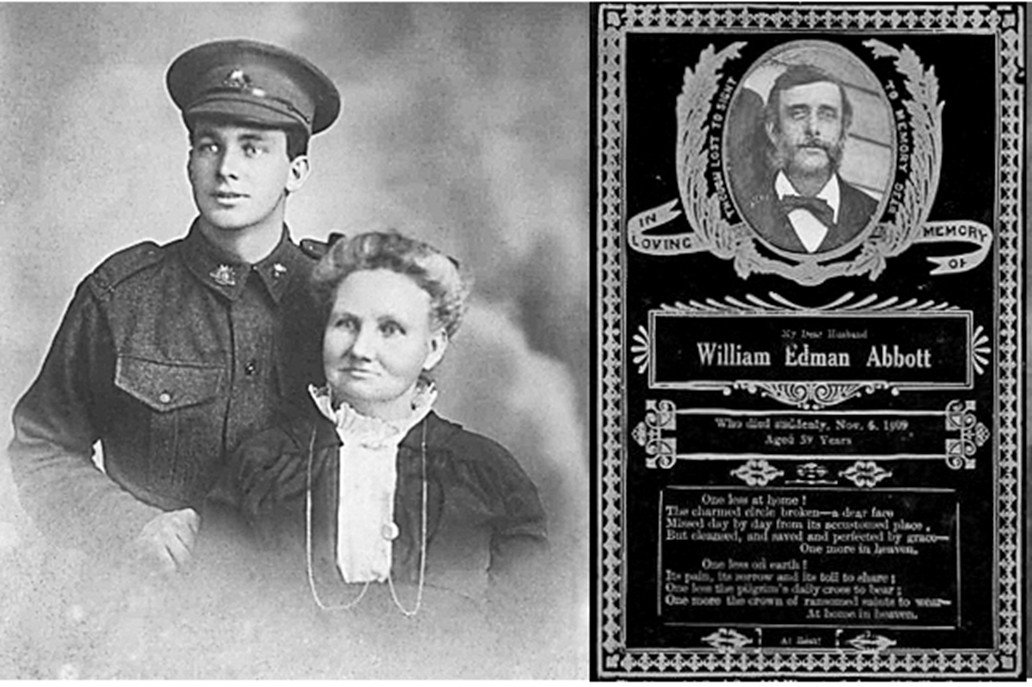

Ermest William Abbott (known as Ern) was born in 1891 at White Hills, Bendigo, Victoria, the son of William Edman Abbott (1850–1909) and Mary Ann “Pollie” Harbour (1862–1939). William came to Australia with his parents in1878 from Shropshire, England, while Pollie arrived only a few months earlier from Duddleston, Warwickshire, England with her sister Alice and family. The couple were married in 1882 at Penrith, New South Wales.

After William and Pollie married, they settled in the Sydney area and raised a large family:

- George Robert Harbour (1883–1932)

- Alice Elizabeth Jane (1885–1968)

- Elsie Emma (1887–1963)

- Ernest William (1891–1916) AIF

- Gertrude twin (1897–1979)

- Herbert Chadville twin (1897–1975) AIF

- Charles Frederic (1904–1960) WW2 AIF

Ern grew up in a household shaped by his father’s pottery trade and their Methodist faith. William was an owner of Abbott & Son, Potters of Five Dock, Sydney NSW, which produced terracotta wares such as chimney pots, butter coolers, and their patented “intense irrigator.” After his schooling, Ern followed in his father’s footsteps and became a potter.

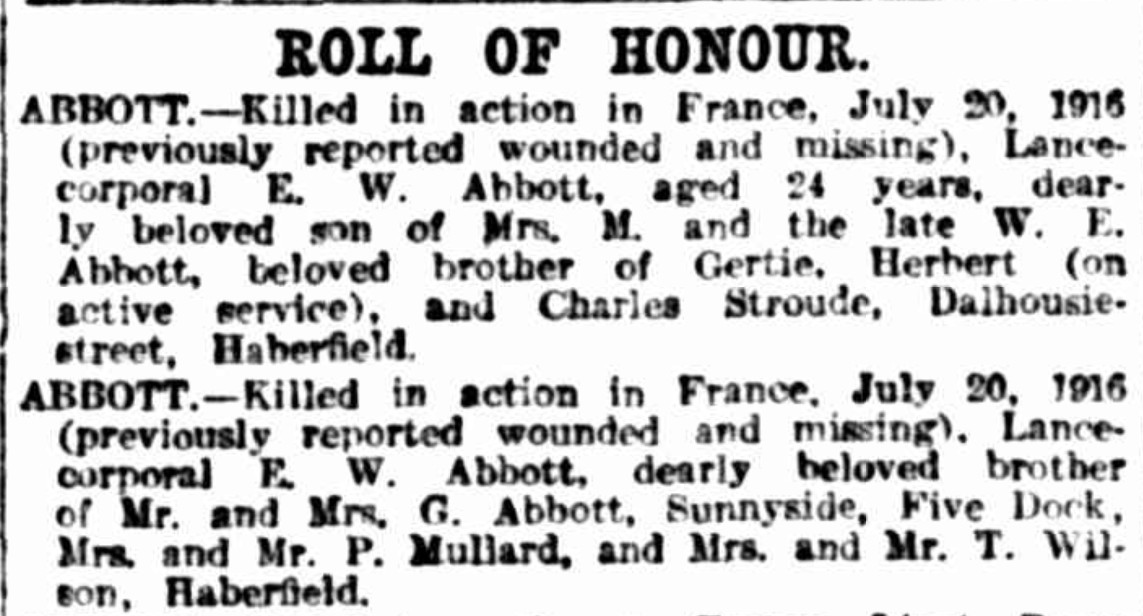

When Ern was seventeen, his father died suddenly while on Park Street, Sydney, after attending a performance of Othello. This left Pollie as a widow with several children still at home. The family remained at “Stroude” in Dalhousie Street, Haberfield, where Ern helped to support his mother and younger siblings.

Off to War

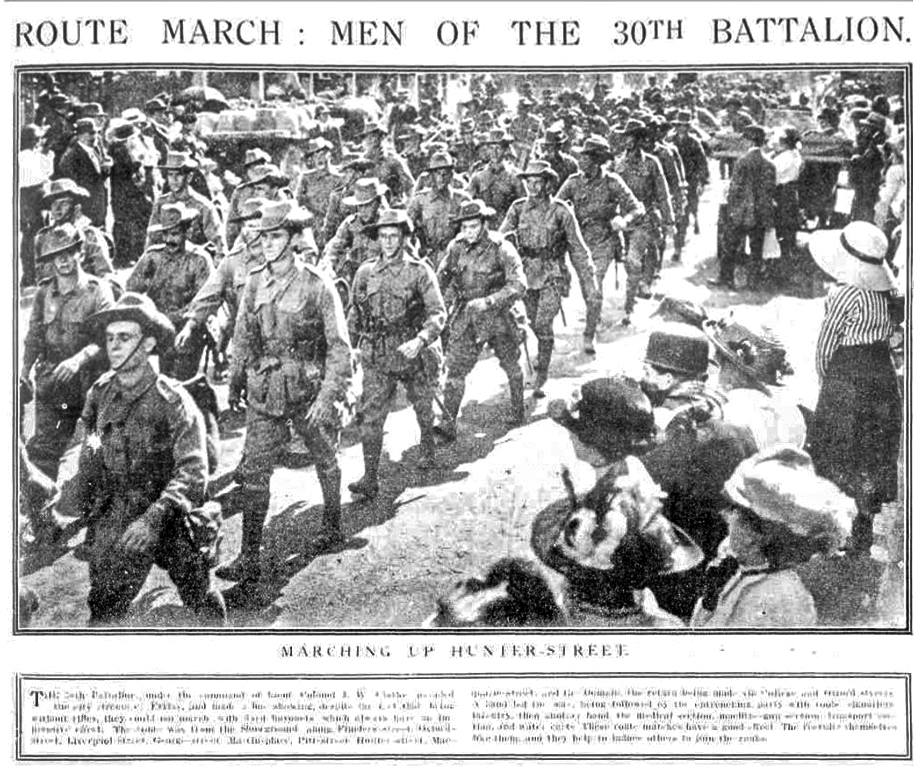

On 18 July 1915, Ern enlisted in the AIF at Liverpool, New South Wales. He was 23 years old and single. His widowed mother was listed as his next of kin at their home in Haberfield. Ern was first posted to the Depot Battalion before being assigned to the 30th Infantry Battalion, A Company. The 30th Battalion was formed on 1 August 1915 at Liverpool, New South Wales. Training commenced in the Liverpool camp, but in September they moved to the Royal Agricultural Show Grounds in Moore Park, Sydney. There were numerous reports of their activities in the papers.

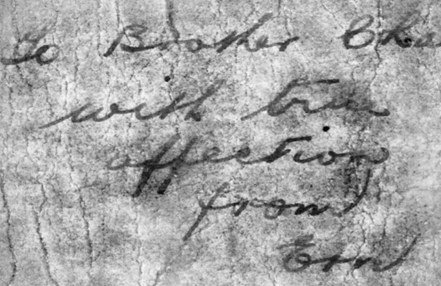

On 9 November 1915, Ern embarked from Sydney on HMAT Beltana (A72) with the 1st Reinforcements of the 30th Battalion. Before he sailed, he gave his 11 year old brother Charles a postcard of his studio portrait and on the back he inscribed, “To Brother Chas, with true affection from Ern”, showing the closeness of the bond between them.

After a month at sea, he disembarked at Suez, Egypt on 11 December. His first seven weeks were spent at Ferry Post guarding the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army and continuing training. February and March were spent at the 40,000 man camp at Tel-el-Kebir, 110 km northeast of Cairo. While there, they were inspected by H.R.H. Prince of Wales. He was promoted to Lance Corporal on 11 March 1916.

For much of April and May Ern was back in Ferry Post, including some time in the front-line trenches there. There were the usual complaints of the heat, water supplies and flies. The Battalion left Egypt for the Western Front on 16 June 1916 on HMAT Hororata and arrived in Marseilles on 23 June. After landing, they were immediately entrained for a 60+ hour train ride to Hazebrouck, 30 km from Fleurbaix. They arrived on 29 June and then encamped in Morbecque. Private F.R. Sharp (2134) wrote home:

“From the time we left Marseilles until we reached our destination was nothing but one long stretch of farms and the scenery was magnificent.” “France is a country worth fighting for.”

The area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. Training now included the use of gas masks and they also would have heard the heavy artillery from the front lines.

On 8 July they were headed to the front lines, first to Estaires, 20 km and the next day 11 km to Erquinghem, where they were billeted at Jesus Farm. They got their first ‘taste’ of being in the front lines at 9.00 PM on 10 July. The journey from Haberfield to France had been swift — less than a year from enlistment to the front line.

The Battle of Fromelles

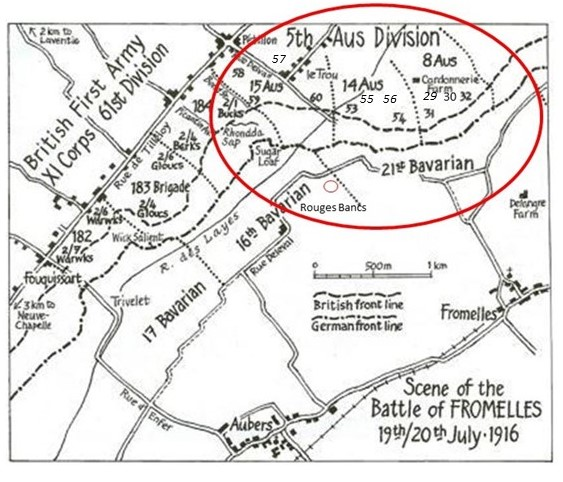

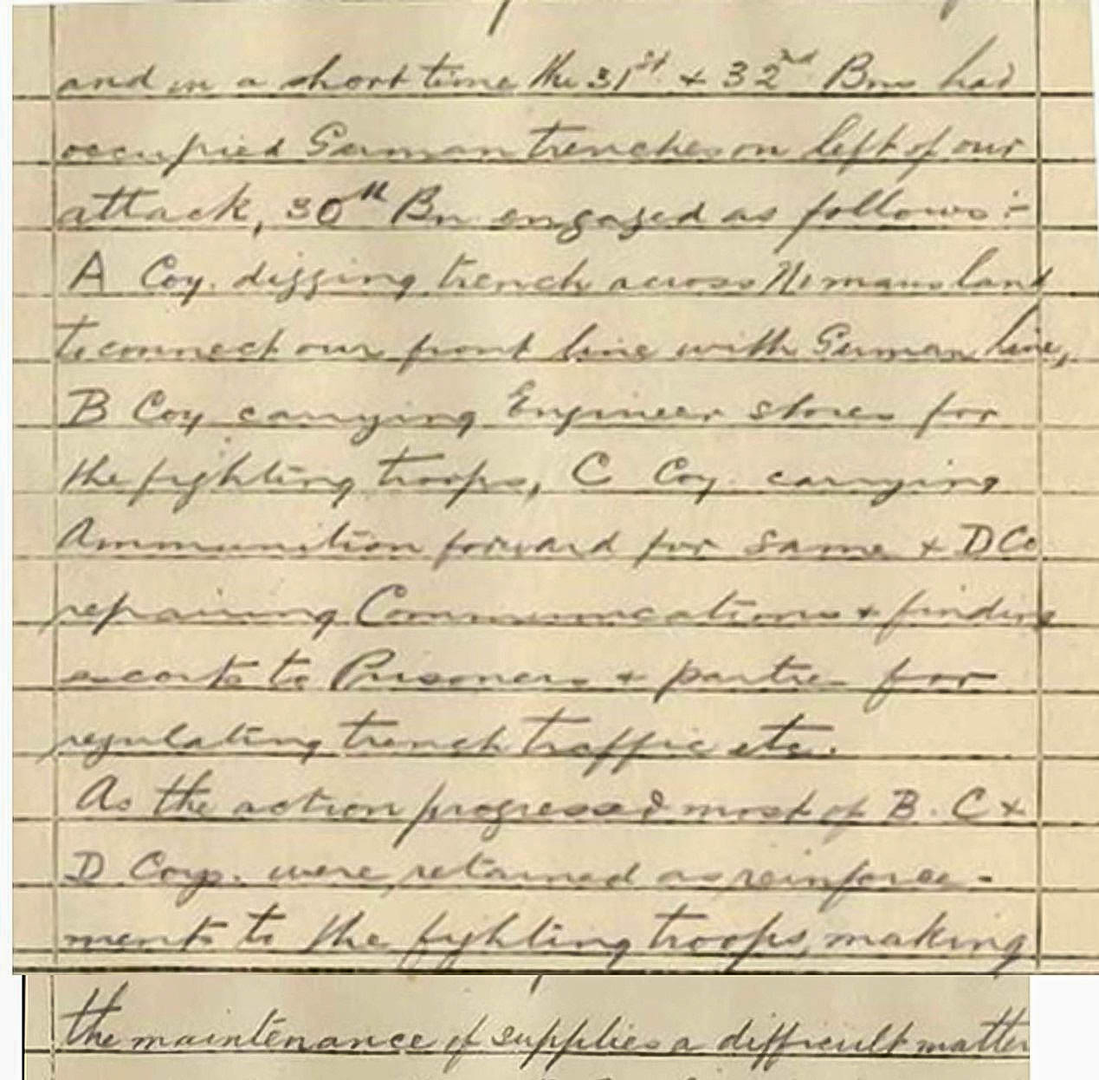

The overall plan for the battle was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The 30th Battalion’s role was to provide support for the attacking 31st and 32nd Battalions by digging trenches and providing carrying parties for supplies and ammunition. They would be called in as reserves if needed for the fighting. The attack was planned for 17 July, but it was postponed due to the weather.

In his final letter home Charles Albert Woods (2194, 30th Bn) summed up the situation he found himself in:

“Since writing last we have shifted from ‘somewhere in France’ to ‘somewhere else in France,’ and are now in the trenches. Whilst writing this the shells are whistling over our heads a ‘treat.’ We are all provided with steel helmets to lessen the danger of being hit in the head with shrapnel, and also with gas helmets, to put on while a gas attack is being made on us.”

Then, on 19 July, the 29 officers and 927 other ranks of the 30th Battalion were into battle. Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. The 32nd’s charge over the parapet began at 5.53 PM and the 31st’s at 5.58 PM.

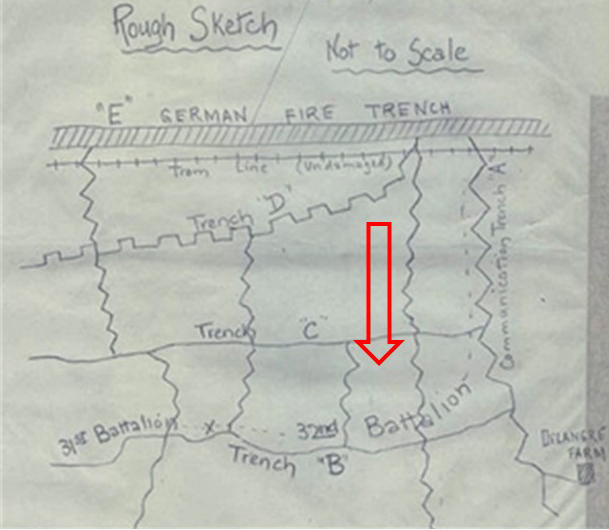

There were machine gun emplacements to their left and directly ahead at Delrangre Farm and there was heavy artillery fire in No-Man’s-Land. While not in the initial rush, the 30th was close behind, digging trenches, carrying ammunition and repairing communication trenches, all while under fire. While suffering significant losses, the initial assaults were successful and by 6.30 PM the Aussies were in control of the German’s 1st line system (Trench B in the diagram below), which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

While the role of the 30th was to be in support, commanders on the scene made the decision to use them as much-needed fighting reinforcements.

By 8.30 PM the Australians’ left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and they were told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

When the 30th was formally called to provide fighting support at 10.10 pm, Lieutenant-Colonel Clark of the 30th reported:

“All my men who have gone forward with ammunition have not returned. I have not even one section left.”

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine-gun fire from behind from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map).

Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, portions of the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers. At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance the 31st could offer was with rifles:

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

By 10.00 AM on the 20th, the Germans had repelled the Australian attack and the 30th Battalion were pulled out of the trenches. The nature of this battle was summed up by Private Jim Cleworth (784) from the 29th:

"The novelty of being a soldier wore off in about five seconds, it was like a bloody butcher's shop."

Initial figures of the impact of the battle on the 30th were 54 killed, 230 wounded and 68 missing. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield.

The ultimate total was that 125 soldiers of the 30th Battalion were either killed or died from wounds and of this total 80 were missing/unidentified.

Ern’s Fate – The Family Waits

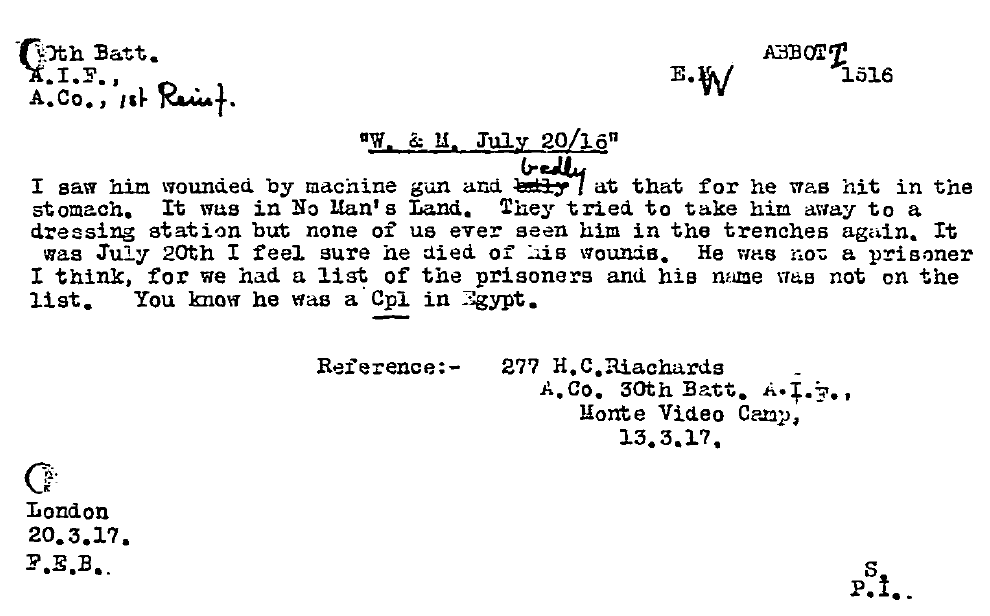

As documented by several witnesses after the battle, Ern was struck down while crossing No Man’s Land, though it is not known when in the battle this may have happened – in the early stages while carrying ammunition or later when joining the fighting. Private Charles Richards (277) gave the most descriptive report -

(note more likely 19 July, not 20 July)

Captain John A. Chapman, an officer of the 30th, confirmed Ern had been hit while in No Man’s Land on the 19th:

“He was wounded in the stomach by a rifle bullet and was last seen in No Man’s Land on the night of 19 July 1916. Nothing further is known.”

As in Charles Richard’s report, there may have been attempts to get Ern back to the Australian lines for treatment, but there are no records of this. However, such details of what happened to Ern took many months to be collected, so all the Army could report to Ern’s family back home was that he was “wounded and missing”.

For his mother Pollie, the waiting became unbearable. While the Army did not have formal information to release, some of Ern’s mates had been in contact with his family. Then, in March 1917 Pollie wrote to Base Records:

“I have had letters from three different soldiers, who told me he was shot in the stomache (sic) and he was in the dressing shed behind the lines and had his wounds dressed from that all trace of him is lost. One soldier who wrote was in the shed at the same time getting his wounds dressed … Is it likely he could be a prisoner and not be able to write, I am sure he would if he possible (sic) could it is eight months now and the suspense is awful.”

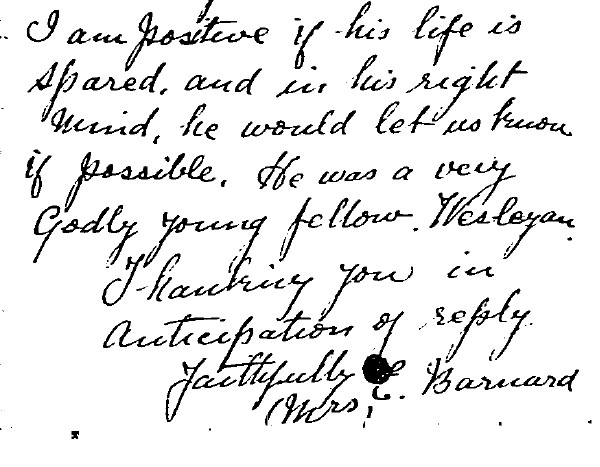

Not only mother, but his brother Herbert (3186, 56th Battalion), who was in the UK at the time, and several of his mates were in contact with the Red Cross seeking news on Ern. While the date of the note below and the relationship to Mrs. E Barnard in the UK are unknown (she had been in contact with Pollie), her letter captures the reality of the likely outcome.

It wasn’t until a Court of Inquiry held in the field on 23 July 1917 that the Army confirmed that Lance Corporal Ernest William Abbott had been killed in action on 20 July 1916. Ern was awarded the 1914–15 Star Medal, British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll, which were issued to his mother. The family placed Roll of Honour notices in the Sydney Morning Herald the following year, remembering Ern as a dearly loved son and brother.

Ern has no known grave. He is remembered at:

- the VC Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial, Fromelles

- Panel 116 at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra

- Haberfield Roll of Honour.

For Pollie, Ern’s death was another blow after the sudden loss of her husband in 1909. Ern’s death at Fromelles was not the only time the Abbott family felt the weight of war.

Family at War

Ern’s 18 year old brother, Herbert ( twin to Gertie), was not far behind Ern in enlisting, 14 February 1916 at Liverpool, New South Wales. Herbert initially served with the 7th reinforcement to the 30th. On heading overseas, they stopped to leave one ship at Suez and then boarded another for England. He went to the Lark Hill Camp in Wiltshire ‘s Salisbury Plain for training and acclimitising to northern winter conditions. There were many shooting ranges and trenches on the Plain with British battalions there at the same time.

Herbert was then on to France on13th November 1916 and he was transferred to the 56th Battalion. He would have been welcomed as one who had lost a brother at Fromelles. However, within 2 weeks, he was in hospital with tonsillitis and then left France with tachycardia (rapid heartbeat) in February 1917. He was in Birmingham War Hospital, Dartmouth and Weymouth Hospitals and was diagnosed with valvular disease of heart before being discharged back to Australia on 22 July 1917.

Ern’s youngest brother - Charles Frederic Abbott - was only eleven when Ern gave him the inscribed studio portrait before leaving for war. That memory remained with him into adulthood. On 5 August 1940, Charles enlisted for the Second World War, serving as Private V31001 in the 2nd Field Regiment, AMF. The war meant a son who never came home from France, another who returned in poor health, and a youngest who later answered the call in a new war.

Pollie lived on until 1939 supporting the survivors and she was granted a military pension to cover Herbert’s medical condition. Herbert married and lived on until 1975. Charles lived until 1960.

Finding Ern

Ern’s remains were not recovered, he has no known grave. After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including 26 of the 80 unidentified soldiers from the 30th Battalion.

We welcome all branches of Ern’s family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification especially from the Abbott and Harbour families of London and Warwickshire. If you know anything of family contacts, please contact the Fromelles Association. We hope that one day Ern will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Ern’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Ernest William Abbott (1891–1916) |

| Parents | William Edman Abbott (1850–1909, Lambeth, London, England – Sydney, NSW) & Mary Ann “Pollie” Harbour (1862–1939, Birmingham, Warwickshire, England – Five Dock, NSW) |

| Siblings | George Robert Harbour Abbott m Margaret McIntosh(1883–1932) | ||

| Alice Elizabeth Jane Abbott (1885–1968) m Percy Mullard | |||

| Elsie Emma Abbott (1887–1963) m Thomas Wilson | |||

| Gertrude Abbott (1897–1979) | |||

| Herbert Chadville Abbott (1897–1975) m Lillian Thew | |||

| Charles Frederic Abbott (1904–1960) m Minnie Petersen |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Robert Abbott (1823–1895, England – Australia) and Harriet Goodrich (1826–1898, England – Australia) | ||

| Maternal | George Harbour (1828–1901, Warwickshire, England – NSW, Australia) and Eliza Vaughan (1828–1899, Warwickshire, England – NSW, Australia) |

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).