Harry CARLIN

Eyes chest 34–38 inches, Hair eyes grey, Complexion hair dark brown

Harry (Hendry) Carlin – A Glasgow Son, An Australian Soldier

Can you help find Harry?

Harry Carlin’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

Harry may be among these remaining unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those from the Carlin and Fallon lines of Ireland and Lanarkshire and Glasgow.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for Harry, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Please contact the Fromelles Association of Australia to find out more.

Early Life

Hendry Carlin, known as Harry, was born on 7 October 1889 in Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Scotland. He was the youngest child of Philip Carlin (1845–1899) born in Ireland), and Elizabeth Fallon (1851–1899) born in Airdrie, Lanarkshire). Harry was part of a large Catholic family of eight children:

- Edward Carlin (1871–1874)

- Rose Ann Carlin (1873–1927)

- Margaret Carlin (1875–1911)

- Elizabeth “Lizzie” Carlin (1878–1957), emigrated to Australia, later married John O’Rourke (955)

- Mary Carlin (1881–1911)

- Philip Carlin (1884–1938), emigrated to Australia

- Joseph John Carlin (1887–1936), emigrated to America

- Hendry (Harry) Carlin (1889–1916)

Both of Harry’s parents died in 1899, when he was only nine years old, leaving the children orphaned. The older sisters, particularly Lizzie and Mary, assumed responsibility for raising the younger siblings. The 1901census recorded Harry as living at 151 Sandyfaulds Street, Hutchesontown, Glasgow, with Lizzie (aged 23, tailoress), Mary (20, teacher), and Philip (17). Harry was listed as a scholar, still attending school at that time. In his late teens, he served with the Imperial Army for three years, according to his NAA file.

This may be where he became a bugler, which he carried into his AIF service.

The role of a trumpeter, a bugler and a drummer was broadly the same, namely transmission of orders in a way that could be heard and understood in just about any circumstance, including the din of battle…. - light infantry or rifle regiments used buglers.

Source: https://www.rootschat.com/forum/index.php?topic=521856.0

Harry emigrated to Australia in 1910 when he was 20. He appears in the New South Wales Unassisted Passenger Lists as “Mr H. Carlin”, arriving in Sydney on 17 November 1910 aboard the Bremen, via Melbourne. Harry found work with the NSW Railways. On 8 January 1914, he commenced duty as a Train Cleaner at Narrabri West Locomotive Depot, becoming a permanent employee just two months later. Narrabari is 500 km NW of Sydney.

Harry quickly became part of the Narrabri West community. He was one of the musicians in a send off for the local Senior Constable in February 1914 and was noted as among those giving speeches for a fellow railway worker in support of the newly married couple.

Source: Presentation at Narrabri. (28 May 1914). Co-operator (Sydney, NSW), p.2. http-//nla.gov.au/nla.news-article239297102.

Off to War - Gallipoli & Egypt

While well settled in Narrabri, Harry felt the call to war and enlisted at Sydney on 30 August 1914, one of the very first volunteers to answer the call. He was posted to B Company, 2nd Battalion and sailed from Sydney to Egypt on 18 October 1914 aboard the HMAT Suffolk. After a short period of training in Egypt, he embarked from Alexandria on 5 April 1915 with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force for the landings at Anzac Cove Gallipoli. He survived the landing, but on 16 May 1915, he was admitted to a Casualty Clearing Station and later transferred to Malta and Alexandria for the treatment for an illness he had contracted while in Egypt.

He rejoined his unit on 3 September 1915 and remained at Gallipoli until the evacuation in late December. With the return of the troops from Gallipoli to Egypt and the huge influx of new recruits from Australia, and major reorganisations were underway with the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five. On 14 February 1916, Harry was transferred to the newly formed 54th Battalion at the Tel-el-Kebir camp, about 110 km northeast of Cairo. The camp contained about 40,000 men. The 54th was made up of Gallipoli veterans from the 2nd Battalion and new arrivals from New South Wales.

By the end of March, much of the basic training in musketry and bayonet use had been completed for all of the new soldiers and they were sent to Ferry Post, on foot, a trip of about 60 km that took three days. It was a significant challenge, walking over the soft sand in the 38°C heat with each man carrying their own possessions and 120 rounds of ammunition. After arriving at the Ferry Post camp they were rewarded with being able to have a swim in the Canal.

During their march, H. R. H. the Prince of Wales visited the troops and they greeted him with “enthusiastic cheers”

Source: AWM4 23/71/2, 54th Battalion War Diaries, March 1916, page 13

The troops spent all of May at the front-line trenches in Katoomba Heights, 8 miles from the Suez Canal guarding from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army. During this time, they took turns occupying front-line trenches, wiring defences, and carrying out patrols. The men became accustomed to trench life and continued their training in preparation for movement to the Western Front. The call to join with the British Expeditionary Force came on 20 June and the 982 soldiers of the 54th Battalion left Egypt. They sailed on the Caledonian for the 10-day trip to Marseilles via Malta.

After disembarking in France, they immediately entrained for a three-day train trip to Hazebrouck, 30 km west of Fleurbaix in northern France. The long train journey north took them through the lush countryside of France — a stark contrast to the sands of Egypt. By 2 July the Battalion was billeted in barns, stables and private houses in nearby Thiennes for a week. Training now included the use of gas masks and exposure to the effects of the artillery shelling. It was hoped that these tests would “inspire the men with great confidence”

Source: AWM4 23/71/6 54th Bn War Diaries July 1916 page 2

On 10 July they moved to Sailly sur la Lys and on 11 July they were into the trenches in Fleurbaix. The health and spirit of the troops was reported as good. After a few days getting exposed to the to the routines of life in the trenches, they moved back to billets in Bac-St-Maur. This area near Fleurbaix which was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long.

The Battle of Fromelles

Major Roy Harrison wrote home on 15 July. With his Gallipoli experience, the tone in this letter was certainly circumspect for the upcoming battle:

“The men don’t know yet what is before them, but some suspect that there is something in the wind. It is a most pitiful thing to see them all, going about, happy and ignorant of the fact, that a matter of hours will see many of them dead; but as the French say ‘C’est la guerre’.”

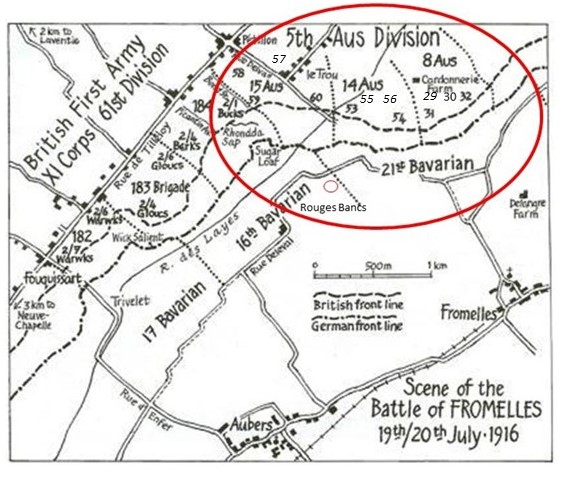

The overall plan was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The main objective for the 54th was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the “Sugar Loaf”’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the 54th and the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfilade fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction.

As they advanced, they were to link up with the 31st and 53rd Battalions. The main attack was planned for the 17th, but heavy rain delayed the operation. The weather soon improved and by 2.00 PM on 19 July they were in back in the trenches, ready for their first major action on the Western Front.

On 19 July, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. At 5.50 PM they began to leave their trenches. They moved forward in four waves– half of A & B Companies in each of the first two waves and half of C & D in the third and fourth. The first waves did not immediately charge the German lines, they went out into No-Man’s-Land and lay down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift.

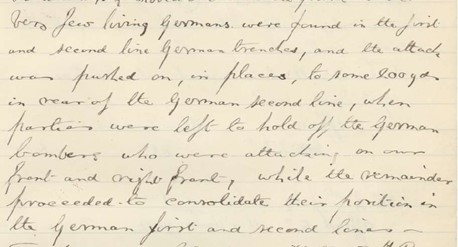

At 6.00 PM, the German lines were rushed. The 54th were under heavy artillery, machine-gun and rifle fire, but were able to advance rapidly. The 14th Brigade War Diary notes that the artillery had been successful and “very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches”.

Some of the advanced trenches were just water filled ditches which needed to be fortified to be able to hold their advanced position against future attacks. They pressed forward nearly 600 yards, linking with the 53rd Battalion on the right and 31st and 32nd on the left, holding a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm. Unfortunately on the right flank, the situation had collapsed. The 60th Battalion had been unable to advance due to devastating machine-gun fire from the Sugar Loaf, leaving the 54th’s flank exposed.

By 2.20 AM the enemy was attacking along the road past Rouge Bancs. Lieutenant Colonel Cass reported that after a counter attack the 53rd were not aware that their flank was no longer protected, allowing the Germans to get behind them and that Australians were being captured. Cass sent a party of 54th men forward to support the line:

“They ran forward with the bayonet and drove the enemy back about 50 yards.”

Despite repeated appeals for artillery support, the position became untenable. At 6.30 AM on 20 July, the 54th received orders to withdraw. The retreat was chaotic and exposed to fire; many wounded men were left behind. Cass again reported:

“I saw scores of men badly wounded and no help at hand to bind them up.”

With the heavy losses and the German counterattacks, the Australians were eventually forced to retreat, but now having to get through the Germans who were also BEHIND them as a result of the exposed right flank. By 7.30 AM on the 20th the 54th were pulled all the way back to Bac-St-Maur, 5 km from the front. In this very short period of time, of the 982 soldiers of the 54th that left Egypt, initial roll call counts were 73 killed, 288 wounded and 173 missing. Among the fallen was Private Harry Carlin.

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. Ultimately, 172 soldiers from the 54th were killed in action or died from their wounds.

Harry’s Fate

Based on several witness statements, Harry was reported as killed in the advanced areas of attack when the 54th were beginning their retreat.

Private Thomas E. Wallings (4909) A Company, 54th Bn reported:

“He was killed on the morning of July 20 just before we commenced to retreat from the position we had arrived at during the charge at Fromelles. He was killed outright by a bomb in the German second line. I saw his dead body in the trench. He was one of my best pals, an Englishman who settled in N.S.W. for some years. … I know nothing as to the burial of his body.”

Private John Adams (255) added:`“… it was reported to me by eye-witnesses … that L/Cpl. Carlin had been shot through the head and was seen lying on the Bochs parapet. … We withdrew from the position so we were unable to bring away or bury our dead.”`

Source: Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Files – Harry Carlin, p 4

However, Sergeant George F. Burnside (2554) provided a markedly different account:

“At Bac-St.-Maur near Armentieres on 19th July, he was killed by the same shell that killed Capt. Taylor and Lieut. Boone, and most likely buried same place as them.”

In a second statement about Taylor and Boone went into further detail about Taylor and Boone:

“On the afternoon of the 19th July at Fleurbaix, the 54th Battalion were waiting in our front trenches, preparatory to the attack. A high explosive shell fell into our trench near Boone, and he was killed instantly. Captain Taylor was talking to Boone at the time, and was also killed.”

But while Taylor and Boone’s remains were recovered and buried — Taylor at Rue-du-Bois Military Cemetery, Fleurbaix (Plot I, Row F, Grave 17), and Boone at Anzac Cemetery, Sailly-sur-la-Lys (Plot I, Row C, Grave 2), Harry’s body was never found. If he was in the advanced area, he could be one of the soldiers placed in the Pheasant Wood grave, as 28 of the 102 unidentified soldiers from the 54th have been found in that grave.

After the Battle

Harry’s sister Lizzie was advised he had been wounded and she received a cable on 9 September confirming he had been killed in action on 28 July 1916. The Army returned his few belongings to his sister Lizzie in Sydney. The official kit store list recorded “Identity Disc, Wallet, Photos, Scapula(r).” The inclusion of a scapular — a Catholic devotional item — shows the strength of Harry’s faith.

Lizzie placed a family notice for Harry in the papers:

“CARLIN.—Lance corp Harry Carlin late of Glasgow, killed in action July 19 or 20 1916 aged 20, dearly beloved brother of Lizzie Carlin, Cambridge-street, Rozelle. R I P.”

In his birthplace of Glasgow, his family ensured he was never forgotten. From 1917 through 1921, annual memorial notices were placed in the Glasgow Observer and Catholic Herald. The fourth anniversary notice in 1920 read:

“Of your charity, pray for the repose of the soul of Lance-Corporal Harry Carlin, Australian Imperial Force, who was killed in action in France, on 19th July, 1916, whilst serving with the British Expeditionary Force, aged 26 years.—R.I.P.”

Harry was awarded the 1914-15 Star Medal, the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll. However, they were not given to Harry’s sister Lizzie (who had raised Harry and was his next of kin and the only beneficiary in his will), they were sent to his brother Philip, due to Army ‘rules’ about such things going to the oldest male in the family.

Harry is commemorated at:

- VC Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial, Fromelles, France

- Australian National Memorial, Villers-Bretonneux, France – his name is engraved among the 10,885 Australians with no known grave.

- Australian War Memorial, Roll of Honour, Canberra (Panel 158) – his name is inscribed among the fallen.

- NSW Government Railway and Tramway Honour Board, Sydney – honouring employees of the NSW Railways who died on service.

- Narrabri West & District Railway Roll of Honour, New South Wales – recognising railway employees from the district where Harry worked before enlistment.

- Narrabri West War Memorial, New South Wales

These memorials demonstrate that Harry’s sacrifice was honoured in both Australia and Scotland — a Glasgow son who became an Australian soldier, lost at Fromelles but never forgotten.

The Roll of Honor at the Narrabri West railway station is a distinct credit to the railway men of the West.

Finding Harry

Harry’s remains were not recovered, he has no known grave. After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including 28 of the 102 unidentified soldiers from the 54th Battalion.

We welcome all branches of Harry’s family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification. If you know anything of family contacts, especially those from the Carlin and Fallon lines of Ireland and Lanarkshire and Glasgow, please contact the Fromelles Association. We hope that one day Harry will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Harry’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Hendry (Harry) Carlin (1889–1916) |

| Parents | Philip Carlin (1845–1899), born Ireland, died Glasgow, Scotland | ||

| Elizabeth Fallon (1851–1899), born Airdrie, Lanarkshire, died Glasgow, Scotland |

| Siblings | Edward (1871–1874) | ||

| Rose Ann (1873–1927, Scotland) | |||

| Margaret (1875–1911, Scotland) | |||

| Elizabeth “Lizzie” (1878–1957, emigrated to Australia, m John O’Rourke) | |||

| Mary (1881–1911, Scotland) | |||

| Philip (1884–1938, baker, emigrated to Australia) | |||

| Joseph John (1887–1936, seaman, emigrated to America) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Edward Carlin (1800–1871, Ireland) and Rose Ward (1801–1871, Ireland) | ||

| Maternal | Edward Fallon (1829–) and Margaret Gammill (1828–1895), Airdrie, Lanarkshire, Scotland |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).