James Ingersol HIGGINS

Eyes grey, Hair brown, Complexion fair

What happened to James Ingersoll HIGGINS

Can you help?

We are searching for relatives who would share this soldier’s DNA (see panel at end of story). Fromelles Association would be very grateful to hear from any family connections.

James and family came from the Geelong area of Victoria with Brunswick connections. James’ DNA story is interesting in itself and his death and burial are very complicated. James was known by his stepfather’s name (Higgins) but was born before his mother married and his birth was registered as James Ingersoll KIDDLE. His father was recorded as James WILLIAMS b abt 1836 England, and Agnes Hicks KIDDLE 1870-1937. James Williams’ son, Frederick James Guy WILLIAMS, married Agnes’s sister, Mary Jane KIDDLE. The children of Mary Jane Kiddle and FJG Williams would carry both the Y line (5 boys) and the Mt line (2 girls). Thus, contacts with family of James or FJG Williams are urgently sought.

James is one of nine men buried in their own sap by his comrades - but several of the nine were recorded by the Germans and are now identified and resting in the new Pheasant Wood Cemetery at Fromelles. Was the original burial site reopened by a German shell?

It is important to find relatives who share James’ DNA, from both sides of the family. Can you help identify James?

A complicated DNA search

An illegitimate birth complicates the DNA search with many family surnames to investigate.

The birth of James Ingersoll Kiddle was registered in 1889 in Brunswick, Victoria. His mother was listed as Agnes Hicks Kiddle 1870-1937 and his father named as 55-year-old James Williams.

At James’ christening, his father’s name is shown as James Kiddle Williams. Was the addition of the Kiddle name an attempt to make the baby seem legitimate?

The Ingersoll middle name for James may indicate a family connection somehow but researchers have not identified any likely links at this stage.

The Williams connection is not proven and the frequency of the James Williams name appearing in records makes it more difficult to trace. However, researchers believe that James Williams may be connected to Frederick James Guy Williams (1871-1923) who married Agnes’ sister (Mary Jane Kiddle 1868-1943) in 1889. Fred’s father was James Williams, born about 1836 so about the same age to possibly be the father listed for James Ingersoll Higgins. Is he the father, or did he accept responsibility on behalf of the Williams’ family? Many theories have been considered but none proven.

In 1893, Agnes Kiddle married Thomas Higgins 1869-1954 when James was 3. They went on to have eight children from 1894 to 1919 – Roy (died as an infant), Vera, Gilbert, Gerald, Irene, Alice, Alan and Thomas jnr.

While researchers do not believe that Thomas Higgins is James’ father, his history was investigated. In doing so, it was discovered that Thomas had changed his name from Kibble. It seems that Thomas had been in care as a boy where he acquired the Higgins name. He came from convict stock and it is possible the name change was to distance him from the convict ancestor. Given the similarities of the Kibble and Kiddle surnames, researchers investigated further but no connection was found.

James’ life before the war

Young James seems to have adopted the Higgins surname and grew up as the eldest son in the large Higgins household in Geelong. The family lived originally in Myers Street but then moved to Geringhap Street; both homes were not far from both the Corio Bay beach and the Geelong Football Club.

On his enlistment papers, James listed his occupation as a labourer but electoral rolls from 1913 lists him as a chauffeur. His mother also describes his pre-war training as being in the electrical engineering field and employment as a stoker. Perhaps describing himself as a labourer indicated that he had a preference for allocation to the infantry rather than being directed towards being a sapper or engineer. Regardless of the reason, his skills were well suited to the army.

James was an active member of the Methodist Church and his name was included amongst the 107 young men from the Yarra Street Methodist Church who enlisted in the twelve months to October 1915. As he enlisted on the 14th of July 1915, it is highly likely that James was amongst the congregation for the unveiling of the church’s Honour Rolls, described in part:

“170 men from the camp voluntarily marched into the service, which was greatly enjoyed by them.”

It is probable that the camp referred to in the news article was the training camp then set up in the Geelong showgrounds.

Enlistment and training

After enlisting in July 1915, James began training in the Geelong camp before moving to Broadmeadows, the main Victorian training camp just ten miles outside Melbourne. Once there, James was assigned to the 3rd reinforcements, 29th Battalion in December 1915.

Training continued until the 3rd reinforcements left Melbourne on HMAT A70 Ballarat on 18 February 1916. They arrived in Port Suez, Egypt on 22 March 1916 and were taken on strength with the main Battalion near Ferry Post. During April and May, the 29th continued training in musketry, bayonet practice and bomb throwing and took part in various drill and tactical exercises. They left Ferry Post for Moascar in late May to ready themselves for France and joining the British Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front.

France

On June 16th, James boarded the troop ship “Tunisian” in Alexandria, heading to Marseilles, arriving there on the 23rd. Their arrival was well received as Private James Lang (858) of Glengarry, Victoria wrote home:

“The French people lined the streets to see us, and gave us a great welcome. Lots of poor woman and young girls started crying. No doubt the poor things were thinking of their own dear ones who had gone to the front.”

The 29th Battalion took the train to Hazebrouck and on to Steenbeque and by the 26th were encamped in Morbeque, about 30 kilometres from Fleurbaix. On 1 July, they moved back to Hazebrouck. Training here included the use of gas masks for the possible use of “lachrymatory shells” – tear gas. Training was tough. One day included a march of 16 miles carrying 75 pounds of kit, which only the youngest and fittest could complete. Private Lang in his letter home described it somewhat light-heartedly:

“We are all well loaded with gear-each of us has a gas helmet, steel shrapnel helmet and goggles, and a fellow looks like a blessed Xmas tree.”

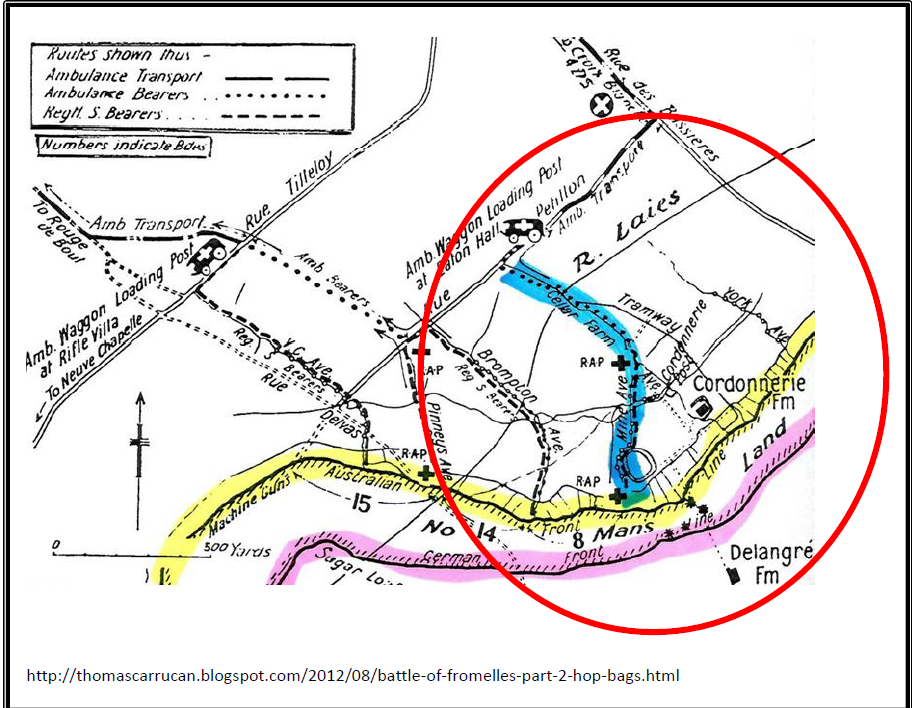

On July 9th they moved to Erquingham, just outside of Fleurbaix and on the 10th they got their first experience in the front-line trenches. They were back in Fleurbaix by the 14th and, on 19 July, they were again in the trenches, ready for the attack. The 8th Brigade’s position was on the left side of the 5th Division, in the Cellar Farm area.

By 8pm, the soldiers were ready, with James’ A company together with D company in the front trenches. Many of the men broke through the forward lines of German trenches looking for what they had been told was a second line. Instead, all they found were a series of shallow drainage ditches.

At 2am, the German counterattack began, but as noted in the War Diaries, “After a struggle, Germans content to stop at their own trench.”

The attack on their right was altered and James’ unit became exposed in a salient jutting into the German lines and were quickly enfiladed by German machine guns. In the end, they basically had to fight their way back to their own lines, 'run for it', or be killed, wounded, or captured.

The nature of this battle was summed up by one soldier from the 29th: "the novelty of being a soldier wore off in about five seconds, it was like a bloody butcher's shop". (Australian War Memorial)

Missing in action – his family searched

More than a month later, Jim’s mother, Agnes, was advised as next of kin that her son was missing in action and his name appeared in casualty lists published in early September 1916. Having no further news of her son from military authorities, Agnes Higgins placed advertisements in Victorian newspapers in the hope that some of the soldiers who had arrived home from France might have news of Jim.

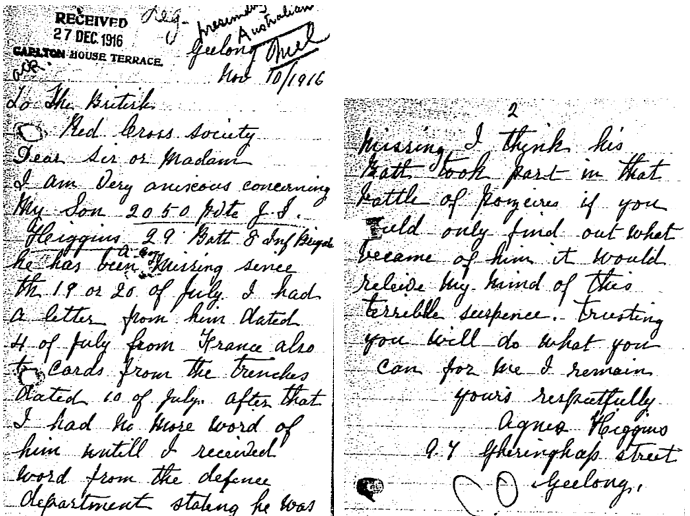

In November, Agnes also contacted the Red Cross to enlist their help to find out what had become of her son. She voiced the feeling of so many other mothers when she said in her letter below “it would relieve my mind of this terrible suspense.”

It was through the Red Cross that Agnes first heard news in March 1917 based on the evidence of Corporal 313 Edward O’Connell about Jim Higgins:

“He belonged to A Co. At Fromelles during the attack he was killed whilst going into No Man’s Land, by a shell. I witnessed the casualty. I know no more.”

Jim’s death by shellfire was confirmed by another 29th Battalion comrade, Pte 2051 Philip Charles Higgins (no relation) who gave a statement dated 24 July 1917 more than a year after the Battle of Fromelles:

“I saw Casualty destroyed by shell fire at Fleurbaix on the 19th July. Casualty was hit just as he reached the front of the parapet. There was nothing left of him. He was a great friend of mine, although not a relative.”

After receiving evidence via the Red Cross, Agnes passed the details on to the army. Eventually, on 12 September 1917 a formal court of enquiry was finalised finding that her eldest son, Pte James Higgins, had been killed in action on 20 July 1916. This news was promptly passed on to the Higgins family via their local clergyman.

Agnes had already received her son’s personal effects on 5 July 1917 so it is likely that the news was merely confirmation of the worst that was already known. The list of personal effects included wallet, postcards, photos, 50 centime note and letter – not a lot, but at least something to remember a lost loved one.

What happened to James? “Buried in the sap..”

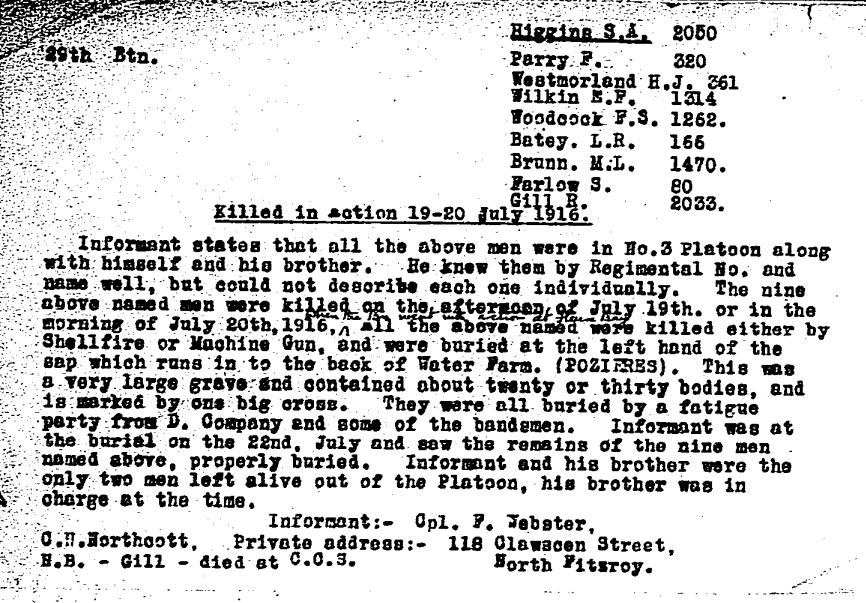

Further evidence was given to the Red Cross that Pte James Higgins was one of nine soldiers killed on the evening of 19-20 July and buried on 22 July as part of a larger group of twenty or thirty in a grave in a sap near Water Farm, Pozieres. This reference to Pozieres was a common mistake of the times relating to French placenames. The sap (a short covered trench / tunnel dug towards an enemy position to provide cover for advancing troops) is probably on the Mine Ave end of the trench (marked in blue in the map above) near where the water hole is marked.

There are also similar notes in these soldiers’ AIF files that they are buried at Fleurbaix, and a general map reference, sheet 36, with the exception being Private Robert Gill who died at the casualty clearing station and is buried at the Bailleul Communal Cemetery Extension.

It would have been chaos in the trenches during the battle and in the immediate aftermath, and it is no wonder records of deaths and burials are often non-existent or contradictory. There are no records of these soldiers being found in this vicinity. However, in 2008 a burial ground was located at Pheasant Wood behind the old German front line at Fromelles that contained the bodies of 250 British and Australian soldiers.

Many of their identities, including Fred, were confirmed through a combination of anthropological, archaeological, historical and DNA techniques.

To date (2024), DNA testing has been able to identify 180 of these 250 soldiers.

Despite being identified as being buried in the sap, four of these nine men - Ernest Wilkin, Frederick Parry, Samuel Farlow and Norman Brumm – were identified in 2010 as being buried in the Pheasant Wood Cemetery! Was the original grave disturbed by shelling or otherwise re-opened necessitating re-burial by the Germans?

With four already identified, are the remaining four (Herbert Westmoreland, Francis Woodcock, Lemuel Batey and James Higgins) still amongst those soldiers now buried at the Pheasant Wood cemetery but unidentified?

On September 5th, 1992, Lambis Englezos spoke with Bill Boyce, 58th Battalion and survivor of the Battle of Fromelles, who said:

“Well my job was to help dig a communication trench across from our own lines to theirs and as such you just didn’t have bayonets…. And the instructions were that when a man in front of you fell who was badly wounded or dead, you just rolled him to one side to the side that most of the fire appeared to be coming from – of course this was in the dark, and we didn’t have very much idea – and put a good heaping of earth over him…”

Researchers investigated the young men identified as buried in the sap and hope to identify more of the nine by persisting in the search for suitable DNA donors.

The four men identified in 2010 were amongst those who had their identification discs returned by the Germans. There are no notes on Jim Higgins AIF file about his identification disc and nor does it appear to have been returned to his mother.

We remain determined to persist in our search for DNA to help identify those buried at Fromelles and hope that Pte James Ingersoll Higgins is amongst them. If you can help us unravel any of the family connections – especially those relating to the names Kiddle, Williams or Ingersoll – we would love to hear from you.

Can you help with DNA? We have located mt DNA donors for James on the female line, but we particularly need Y DNA donors on his father’s line.

| Soldier | James Ingersoll HIGGINS 1889-1916, born KIDDLE (illegitimate) Geelong |

| Parents | Possibly James WILLIAMS note 1 b abt 1836 England, and Agnes Hicks KIDDLE 1870-1937 |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Unknown | ||

| Maternal | Barbara PURVIS b 1837 Harrington, Scotland – 1941 Geelong, and Edward Hicks KIDDLE |

Note. 1. James Williams’ son, Frederick James Guy WILLIAMS, married Agnes’s sister, Mary Jane KIDDLE. The children of Mary Jane Kiddle and FJG Williams would carry both the Y line (5 boys) and the Mt line (2 girls). Thus, contacts with family of FJG Williams are urgently sought.

2. Agnes married James Higgins in 1893, and they had eight children, including daughters Vera, Irene, Alice who would be half-sisters to James and their descendants would carry the Mt DNA line.

3. We are advised that UWCA hold one mtDNA family reference sample. Due to privacy legislation, we do not know the identity of that donor. We are now seeking

- A second mt DNA sample

- A Y DNA sample – particularly from the Williams family

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).