Henry Lamert THOMAS

Eyes grey, Hair brown, Complexion fair

Henry Thomas - A Commendable Commitment

Early Life

Henry Lamert Thomas, born Henry Lamert Marsden, was the son of Frances Amelia (nee Folk) and Merton Charles Moses Marsden. He was born on 17 October 1897 in Orange, NSW, 250 km from Sydney. His brother Phillip was born in 1900 and his sister Lillias in 1902. By 1902 the family had moved to Newcastle, 170 km north of Sydney. Unfortunately, Henry’s father died in 1905, only 32 years old. Francis did remarry, in 1907, to John T. Thomas. Henry and his brother adopted his stepfather’s surname in 1914, though this was not formally gazetted until 1940. Henry worked as a railway clerk with the New South Wales Government Railway and was living in Toronto, NSW in 1915.

Off to War

As soon as he was old enough (18), he enlisted on the 20 September 1915 at nearby Newcastle, New South Wales. He was assigned to the 30th Battalion, 4th Reinforcements, B Company and was sent to Liverpool to begin his military training.

He remained in Australia until 11 Mar 1916, when he departed to Egypt from Sydney, New South Wales on board HMAT A67 Orsova and arriving in Suez on 14 April. He was finally joined with the full 30th Battalion on 25 May 1916 at Ferry Post, on the Suez Canal. Most of the soldiers had been in Egypt since the beginning of the year, and the common complaints were of the heat, water supplies and flies. enry was soon headed for the Western Front, leaving on 16 June 1916 on HMAT Hororata and arriving in Marseilles on 23 June. After landing, there was a 60+ hour train ride to Hazebrouck, 30 km from Fleurbaix. They arrived on 29 June and were encamped in Morbecque.

Private F.R. Sharp (2134) wrote home about his observations:

“From the time we left Marseilles until we reached our destination was nothing but one long stretch of farms and the scenery was magnificent.” “France is a country worth fighting for.”

Training now included the use of gas masks and they also would have heard the heavy artillery from the front lines.

On 8 July they were headed to the front lines, first to Estaires, 20 km, and the next day 11 km to Erquinghem, where they were billeted at Jesus Farm. Henry got his first ‘taste’ of being in the front lines at 9.00 PM on 10 July.

The Battle of Fromelles

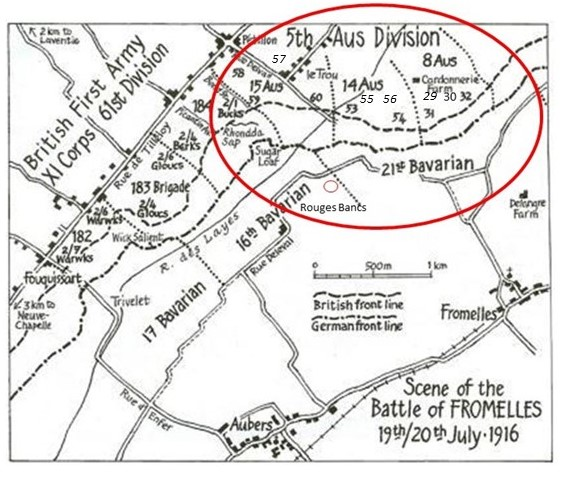

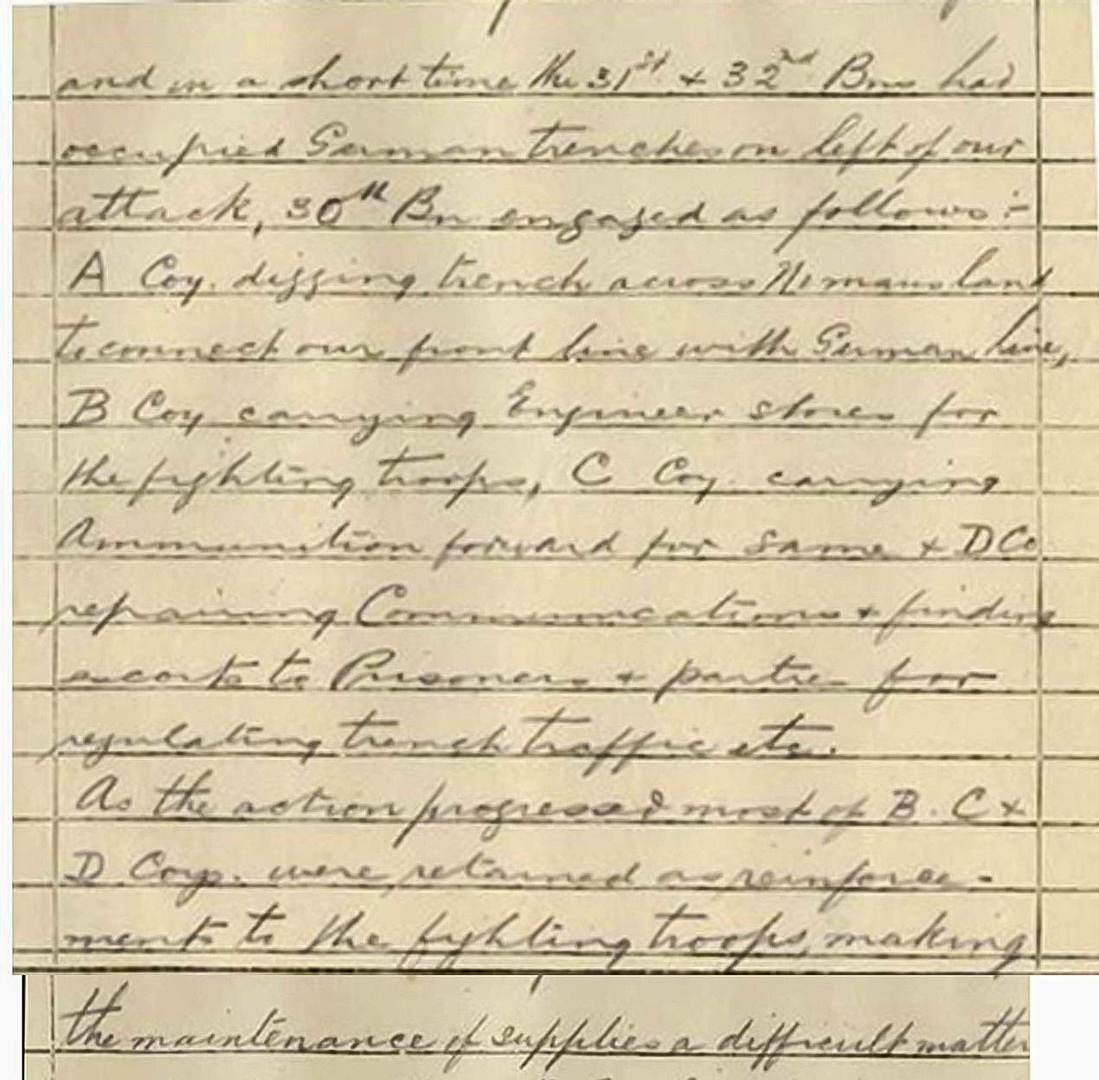

A week later, they got orders for an attack, but it was postponed due to the weather. Then, on 19 July, the 29 officers and 927 other ranks of the 30th Battalion were set to go into battle. The 30th Battalion’s role was to provide support for the attacking 31st and 32nd Battalions by digging trenches and providing carrying parties for supplies and ammunition. They would be called in as reserves if needed for the fighting.

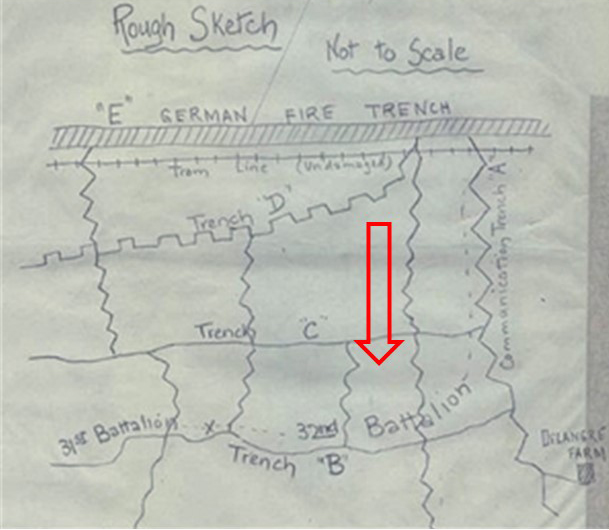

The 32nd’s charge over the parapet began at 5.53 PM and the 31st’s at 5.58 PM. There were machine guns emplacements to their left and directly ahead at Delrangre Farm and there was heavy artillery fire in No-Man’s-Land. The initial assaults were successful and by 6.30 PM the Aussies were in control of the German’s 1st line system (Trench B in the diagram below), which was described as:

practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom

While their planned role was to be in support, commanders on scene made the decision to use the 30th as much-needed fighting reinforcements. A necessary act, but it had consequences as it interfered with the flow of supplies for the fighting.

By 8.30 PM the Australians’ left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and the 32nd Battalion was told that:

“the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

When the 30th was formally called to provide fighting support at 10.10 pm, Lieutenant-Colonel Clark of the 30th reported:

“All my men who have gone forward with ammunition have not returned. I have not even one section left.”

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine gun fire from behind from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map). Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, portions of the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers. At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance that could be offered was with rifles..

The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.’

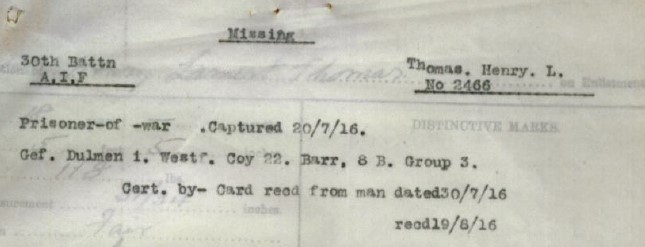

Thomas was captured as a POW at about this time.

“At the time of my capture I was with a party of four others in a shell hole between the first and second trenches. We were unable to retire, as immediately we were seen in the shell hole we called down machine-gun fire. We decided to stay in the shell hole and try to get back under cover of darkness, but about 5 or 6 o’clock in the morning of the 20th the Germans came out of the trenches and surrounded the shell hole in which we were, and we were forced to surrender.

I had been slightly wounded by shrapnel in first going over the trenches, but the wound was very slight and at the back of the left knee.”

By 10.00 AM on the 20th, the Germans had repelled the Australian attack and the 30th Battalion were pulled out of the trenches. The nature of this battle was summed up by Private Jim Cleworth (784) from the 29th:

"The novelty of being a soldier wore off in about five seconds, it was like a bloody butcher's shop."

Initial figures of the impact of the battle on the 30th were 54 killed, 230 wounded and 68 missing. The ultimate total was that 122 soldiers of the 30th Battalion were either killed or died from wounds and of this total 80 were missing/unidentified. To date (2024), 26 of those missing have been later identified and are buried in the Pheasant Wood Cemetery. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large amount of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield.

An Anxious Family

The Army contacted Henry’s family soon after the battle, but all the Army could advise was that Henry was ‘missing’. His mother Francis, hopeful that he would not proven to have been killed, wrote back at the end of August asking:

“Can you possibly ascertain for me if he has been made a prisoner of war, if so would letters be delivered to him.”

“Mrs Hunt, wife of Major Hunt at present in service with 55th Battalion has assured me that you will use your best efforts to help me in my time of anxiety.”

While there was information available in August (below), with the need to confirm advice of a soldier’s fate and all the confusion from the aftermath of the battle, the Officer in charge of Base Records back home had yet to be advised.

While the ‘formal’ records in his file are a bit confusing about what was being communicated to the family, it is clear that Francis Thomas had gotten the news of Henry being a POW, as she notes this in a letter she wrote to the Army on 6 November 1916. While being a POW is not ideal, at least some of the anxiety of Henry being ‘missing’ was relieved. Also, she had been sending parcels and letters to Henry fortnightly since he had left Australia in March. At least one welcomed parcel had gotten through before he was captured, as noted in what he wrote about his POW experience:

“I was very lucky in having a cake of ‘Lifeboy’ soap in my pack, which I had received in a parcel from home. I had put this in my pack just before going over the top, and I was very glad to have it with me, as it is impossible to buy soap in Germany.”

Life as a POW…bearable

Henry was a POW for 15 months before he escaped. He gave an extensive factual description about his treatment as a POW, in which he states was generally well treated. Excerpts are below and the full version can be found in his Army File.

“After being captured I was brought into the German trenches, and with a party of three others taken down a communication trench on to a road, where we joined up with a party of 20 or 30 other men of the 8th Australian Brigade. This party was then marched back to Loos, and from there to Lille, which I think we must have reached about midday.”

“As soon as we got to the prison, we were served out with some soup – at least, I think they called it soup. I should not like to say what it was made of; I should think it was made of turnips, perhaps.”

“We had no provision whatever made for our comfort at Lille except the straw mattresses in the room. We were given no blankets and no means of washing except the tap in the yard, but there were no buckets or basins which we could use for washing (note – he did have his cake of ‘Lifeboy’ from home!).

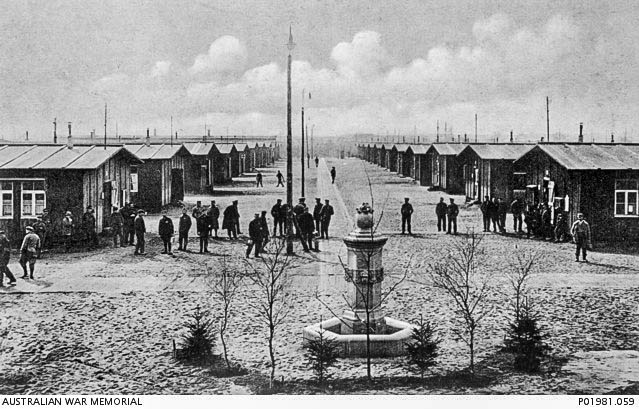

He was soon moved to the large camp at Dulmen and was there from 24 July until 4 September.

“When I first got to the camp I reported ‘sick,’ but I did not mention my wound. The doctor saw me and gave me some medicine and told me not to eat too much (emphasis added). I looked at him and was absolutely speechless and could not say a word. He did not appear to intend his advice to be taken as a joke.”

“In the morning, at six o’clock, about twice a week, we received what we used to call ‘sandstorm’ because it was like the fine dust of the Egyptian Desert. I believe that this was really bone dust. We came to the conclusion that it must be this. This was made into a sort of soup. It was like a very thin porridge. We got the usual old ladleful of this stuff. Dinner was served at 1 p.m. This consisted chiefly of cabbage and water, or turnips and water, or mangolds and water.”

“What I have said about the food might make it appear that there was plenty of it and some variety, but it was really starvation rations, and it was a common thing for men to faint on parade from general weakness, and on getting out of bed in the morning we often had a faint dizzy feeling.”

He does mention that there were Canteens available where the POWs could buy limited supplies of sardines, honey, jam, coffee, razors, pencils/paper, etc:

“The only facility we had for exercise in this camp was walking about the camp. There were no outdoor games of any sort. The only indoor amusement was playing cards and draughts on a board which we made ourselves.”

On 4 September 1916 he was moved to the camp at Erkrath, near Dusseldorf.

“This was the best accommodation I saw in Germany for war prisoners. It had a wooden floor, and was heated by a stove in the middle of the room burning coke, and was lit by electricity.” He also noted that the beds were very comfortable and that the food was good.

“We received letters and parcels while I was at Erkrath. The first parcel which I received came about three weeks after I had arrived there. This was the first parcel I had received at all since I was taken prisoner.” He also describes that all communications were censored and that they could only write one postcard per week and two letters per month.

Henry was determined to resisting to work for the Germans and he had (successfully) adopted a ‘passive-aggressive’ approach -

“…it was thought I had not been working well. I had determined not to do so, and had behaved in such a way as to be bought before the doctor and the Fabrik Meister. I told them that my heart was weak and that I could not work properly...”

“On another occasion I was ordered to wheel a large barrow full of white clay. As I did not much fancy the job, I went up to the Fabrik Meister and told him I had hurt my shoulder. The doctor said that I had dislocated it, and I was excused work, and as the result of this I was never put to the work of wheeling a big barrow again.”

In mid-February 1917 he was singled out because of his work efforts and was moved to Munster Camp 1.

“When I got to Munster I went before the doctor for my heart. He sent me to bed for five days to get it right! At the end of that time I went before him again, and he then marked me A1, which meant that I was fit as I was for hard work. I do not know the name of the doctor, but he was no fool.”

Heny left Munster 1 on the 4th April 1917 and was sent to the Duisberg Meidrich camp, but he continued his ‘resistance’.

“We were employed in various ways in this very big factory, all in connection with tar distillery. At first I got 1 mark a day, but I would not work satisfactorily, and I was taken off and put on to punishment work (a “straf” job), which was the best job I struck in Germany, and I stuck to this. I did practically no work. I had to empty seven or eight wagons of naphthaline per day, and each wagon took about seven minutes to empty.”

Escaped, but there was still a war going on

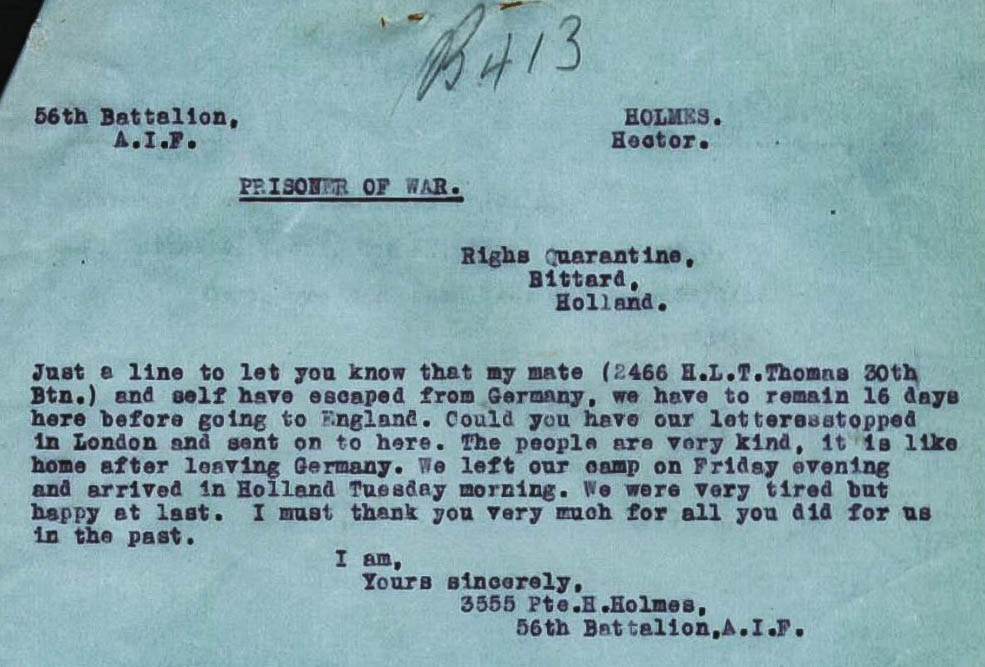

While doing little to help the Germans, he was still a prisoner, and after being in the Duisberg Meidrich camp for seven months, he and Hector Holmes (3555) of the 56th Battalion managed to escape from the camp on 27 October 1917. Henry provided no details, but travelling by night they successfully made their way to their freedom in Holland on 31 October. He was sent to England on 23 November and on 26 November his family were advised of his escape and safe arrival.

While he had only recently escaped, all able soldiers were still needed for the War. He was soon assigned to duties with 14th Training Battalion and then to the Reserve Brigade Australia Artillery in Heytesbury (between Bath and Southampton) in February 1918. At end of July 1918 he was sent to War operations. He notes that he was a Temporary Sergeant in the 5th Battery Australian Field Artillery (though his records state he was in the 2nd). He had also ‘found’ his way back into the area of the Somme and was there until the War ended in November.

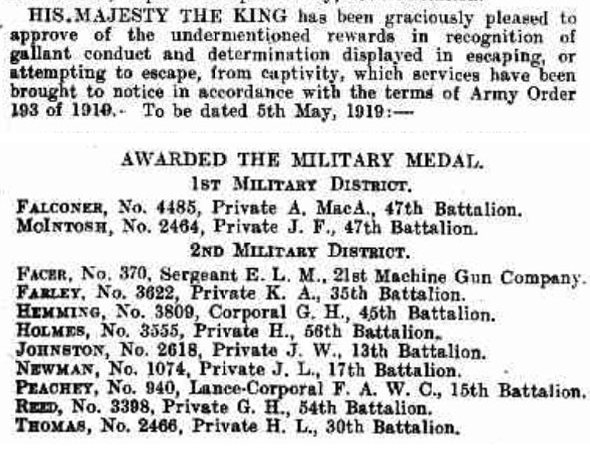

With thousands of soldiers needing to be sent back to Australia at the end of the War, returning home was not a quick process. Henry had to wait until mid-May 1919 to board a ship and he did not arrive home until early July. In 1920, Henry was awarded the Military Medal, which was issued to soldiers who were able to escape from the POW camps. The announcements were in both the London and Australian Commonwealth Gazettes.

Home, but then went back to War – WW2

Once he got home, Henry returned to working as a clerk with the railroads in Toronto, NSW. He married Nellie Webb in 1922. They had two sons and a daughter. They did move around some, presumably with the railroad, as he rose to be a Principal Clerk. In 1925 their second son was born in Picton NSW, southwest of Sydney; when Henry enlisted in WW2 in 1940 they were living in Casino, far north NSW; and in 1943 they were at 15 Lovell Road, Eastwood, an area of Sydney, where they lived for more than 30 years. While seemingly well settled into a non-military life (and having teenage children), Henry answered the Call to War again, enlisting 24 July 1940.

He left Australia at the end of December 1940 to a posting at Kantara, Egypt, on the Suez Canal. He was doing clerical work and was promoted several times, finally to Lance Sergeant. He returned to Australia at the end of March 1942, but was still in active service. In August 1942 he was sent abroad again, this time to Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, working in Headquarters. He remained in PNG until May 1945, with some breaks to allow him to be home. He was promoted to Sergeant, then to Warrant Officer and on 15 September 1945 to Lieutenant.

A Commendable Commitment

Henry finally left the service of his country in December 1945, two wars and 15 months as a POW, a commendable commitment. He lived to be 91 years old, passing away on 16 November 1988. Nellie died a year later.

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).