Royce John BETANCOR

Eyes brown, Hair dark brown, Complexion sallow

Royce John Betancor - “Remember Me to the Fellows”

Can you help us to identify Roy?

Roy Betancor’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

Roy may be among these remaining 70 unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in South Melbourne, Lancashire UK, Ballyvalough, County Antrim Ireland and the Azores.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for Roy, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Early Life

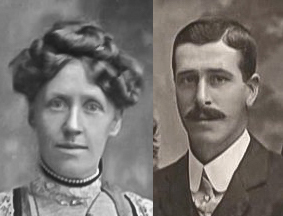

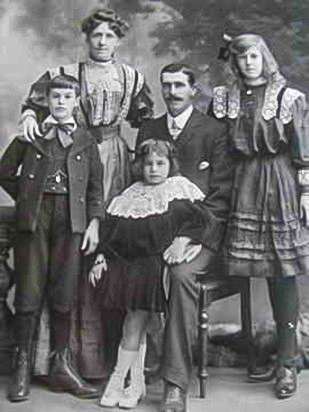

Royce John Betancor, who was known as Roy, was born in Melbourne on 31 August 1895, the middle child of John Francis Betancor and Ella Stewart Green of South Melbourne. He had two sisters, Ella, known as Weenie, and Viola:

- Ella (Agnes Ella May) 1894-1981

- Royce John (Roy) 1895-1916

- Viola Dorothy 1902-1977

from Left, Roy about 12, Viola 6, Weenie (Ella) 14, about 1908.

Roy’s paternal grandfather, Emanuel Betancor, was a Portuguese sailor (Azores). The surname is Spanish and Norman French in origin. Ella’s father was born in Lancashire, and her mother came from Ballyvalough, County Antrim, Ireland. Roy’s parents were married in 1891 and were long term residents of Albert Park and South Melbourne.

John was a paper hanger and painter and the family were well supported. In 1903 the family lived at 69 Raglan St South Melbourne. The family later moved a few streets to 42 Withers Street, Albert Park, much closer to the beach as well as the lake. As Ella had six sisters and three brothers, there was a large extended family nearby. The children attended South Melbourne (Eastern Road) State School.

After he left school, Roy trained as a dental mechanic, who at the time created dental prosthetics and appliances. He worked for Mr D. Shanasy, a Collins Street dentist, in the heart of Melbourne. He was also a football player and member of the Albert Park Rowing Club (now Albert Park South Melbourne Rowing Club), having joined in the month before Australia entered the war. Though he had no recorded rowing wins, the Club reflected a commitment to local sport and community there were many news items and they later had memorial notices about him.

Off to War

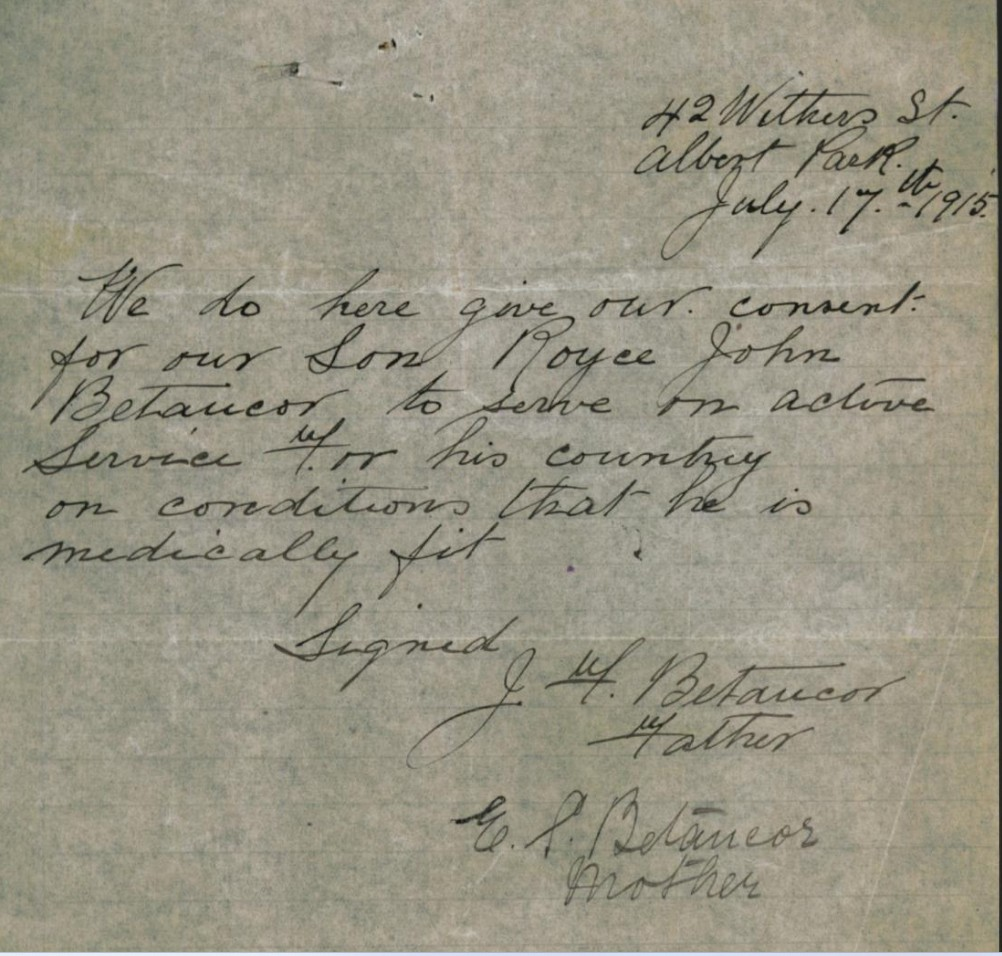

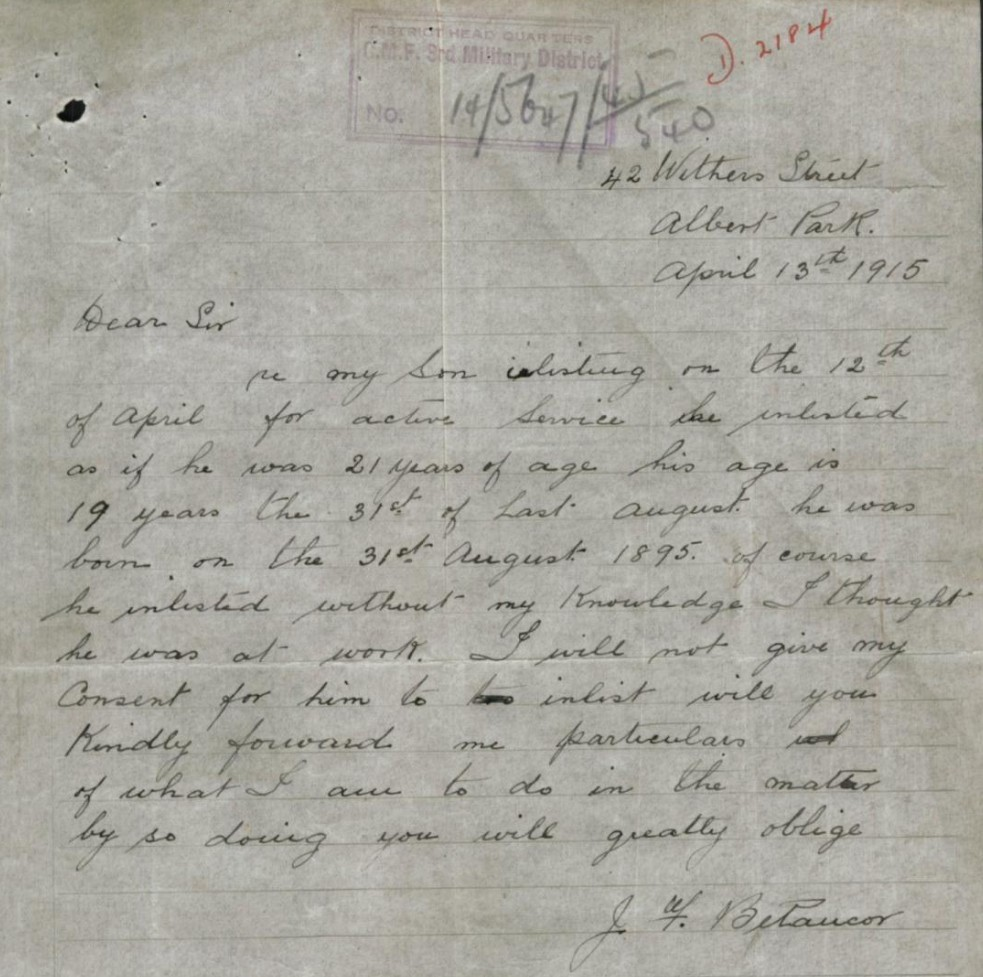

Roy was keen to serve and he enlisted on 12th April 1915. However, as he was underage, he gave his age as 21 so as not to require parental permission, but he was found out by his father and was discharged.

Eventually securing his parents’ consent, he successfully enlisted on 2 August 1915 in Geelong, Victoria.

While Gallipoli had shown the Army that dental work was important in keeping soldiers in the field and dentists and technicians had become roles in the Army, but Roy was assigned to an infantry role, the 6th Reinforcements for the 24th Battalion. He began his military training at the Broadmeadows Camp and on 27 October 1915, he embarked from Melbourne aboard HMAT Ulysses bound for Egypt. After arriving in Alexandria, he was sent to the camp at Tel-el-Kebir. With the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five, major reorganisations were underway.

The 60th Battalion was raised in Egypt on 24 February 1916 at the 40,000-man Tel-el-Kebir camp, which was about 110 km northeast of Cairo. Roy was reassigned here, in B Company, on 26 February. Roughly half of the soldiers were Gallipoli veterans from the 8th Battalion, a predominantly Victorian unit, and the other half were fresh reinforcements from Australia. Their training continued to build the men into the new fighting units. In mid-March, they were inspected by H.R.H the Prince of Wales.

After a month of training at the large camp at Tel-el-Kebir, they had a two+ day, 50 km march in thermometer-bursting heat across the Egyptian sands from Tel-el-Kebir to Ferry Post, near the Suez Canal. Prior to marching, only ½ pint of water per bottle was available.

Source- AWM4 23/15/1 15th Brigade War Diaries Feb-Mar 1916 p 6.

They remained at Ferry Post until 1 June continuing their training and guarding the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army. Their time in Egypt was not all work, however. A 5th Division Sports Championship was held on 14 June, which was won by the 60th Battalion’s 15th brigade. On 17 June they received orders to begin the move to the Western Front and were soon on trains to Alexandria. The majority of the battalion, 30 officers and 948 other ranks, embarked in Alexandria on the transport ship Kinfauns Castle on 18 June 1916. After a stop in Malta, they disembarked in Marseilles on 29 June and were immediately put on trains, arriving in Steenbecque in northern France, 35 km from Fleurbaix on 2 July.

This area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. On 7 July they began their move to the front, arriving in Sailly on the 9th. Now just a few kilometres from the front, their training continued, although with a higher intensity, I’m sure. The move to Fleurbaix continued and Roy was into the trenches for the first time on 14 July.

The Battle of Fromelles

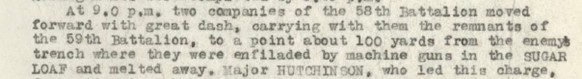

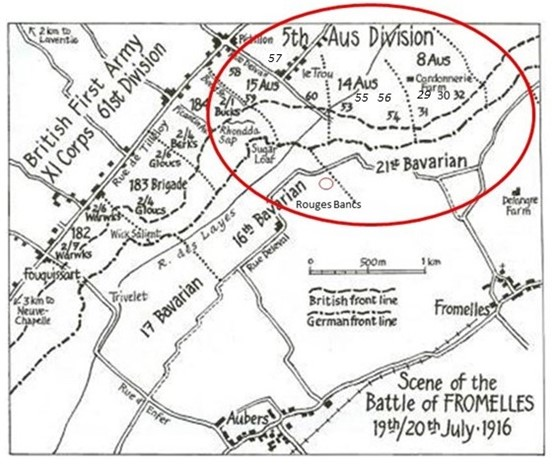

The battle plan had the 15th Brigade located just to the left of the British Army. The 59th and 60th Battalions were to be the lead units for this area of the attack, with the 58th and 57th as the ‘third and fourth’ battalions, in reserve. The main objective for the 15th Brigade was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines.

If the ‘Sugar Loaf’ could not be taken, the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfilade fire from the machine-guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 59th and 53rd Battalions on their flanks. The 60th Battalion faced an especially difficult position in the assault, directly opposite from the ‘Sugar Loaf’. Roy wrote to his rowing club on 15 July 1916, just days before the Battle of Fromelles, and this offers a glimpse into his mindset and surroundings:

“Tell the boys I am still going strong, and that this is a far better country than Egypt. We had a fine trip over and, happily, did not come in contact with any submarines (tinfish). We received a wonderful reception from the French upon our arrival, and ever since they have treated us right royally — doing everything in their power to please us.

On the journey across I met Cecil Leslie and a number of fellows from other clubs. Since landing here I have met Herb Dickinson, who is looking well and has reached the important rank of Captain.

At present, we are not far from the German lines, billeted in a farmhouse that has almost been demolished by shell fire. The artillery and machine guns, as I am writing, are all around us and causing a terrible din. However, things are not too bad.

While on sentry last night, I had a bit of luck — a bullet struck the ground right beside my foot.

This is a flat country, extensively cultivated, and during the railway journey we passed many fine towns. I am glad to know that the clubs are keeping the gang going with interclub and challenge racing until the boys return.

Hoping you will remember me to the fellows.”

This letter did not reach the family until late August. On 17 July, they were in position for the major attack against the Sugar Loaf position, but it was postponed due to unfavourable weather. There was a gas alarm, but luckily it was just that. Two days later, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. A fellow soldier, Private Bill Boyce (3022, 58th), summed the situation up well: `“What have I let myself in for?”`

Source: Australian War Memorial Collection C386815

The Aussies went over the parapet at 5:45 PM in four waves at 5 minute intervals, but then lay down to wait for the support bombardment to end at 6 PM. Roy’s B Company and A Company were in the first two waves and C & D in the next two. With the firepower at the ‘Sugar Loaf’, casualties were immediate and heavy. The 15th Brigade War Diaries captures the intensity of the early part of the attack – “they were enfiladed by machine guns in the Sugar Loaf and melted away.”

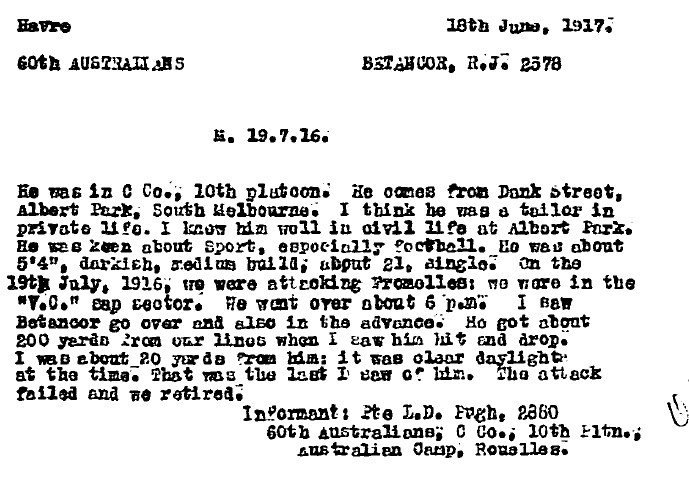

The British 184th Brigade just to the right of the 59th met with the same resistance, but at 8.00 PM they got orders that no further attacks would take place that night. However, the salient between the troops limited communications, leaving the Australians to continue without British support from their now exposed right flank. Roy was in the Australian advance and Private Llewellyn D. Pugh (2880), C Company, 60th Battalion stated that “he got about 200 yards from our lines when I saw him hit and drop.”

Source - Red Cross Wounded and Missing File – John Royce Betancor, page 4

Some Australians got to within 90 yards of the enemy trenches and one soldier said he “believed some few of the battalion entered enemy trenches and that during the night a few stragglers, wounded and unwounded, returned to our trenches.”

Source - AWM4 23/77/6, 60th Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 3.

Fighting continued through the night. With known high casualties in the 60th, they were relieved by the 57th Battalion at 7.00 AM. Roll call was held at 9.30 AM. In the ‘Official History of the War’, C.W. Bean said “of the 60th Battalion, which had gone into the fight with 887 men, only one officer and 106 answered the call.”

Source - Chapter XIII page 442

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The final impact of the battle on the 60th was that 395 soldiers were killed or died of wounds, of which 315 were not able to be identified.

Roy’s Fate – Killed as he was well into the advance

As noted above, Roy made it well into the advance on the Sugar Loaf when he was killed. Another witness stated that he found Roy’s body several weeks after the battle, but as there was no truce, recovery was not possible and he buried him in a shell hole and took his ID disc as proof.

Private William J. Cunningham (3075), 59th Battalion:

“From Lieut. Francis M. Diamond 772 C. Coy, 60th Battn. I obtained information about this man who was a friend of mine. This officer showed me the disc that had belonged to this man. He informed me that Betancor had been reported missing after the attack at Fromelles on July 19th 1916, and that he (Diamond) had gone out afterwards and found the body of the missing man in No Man's Land between the two front lines (German and British). He did not bring the man in, but buried him in a shell hole and took his disc for identification purposes.”

Legacy

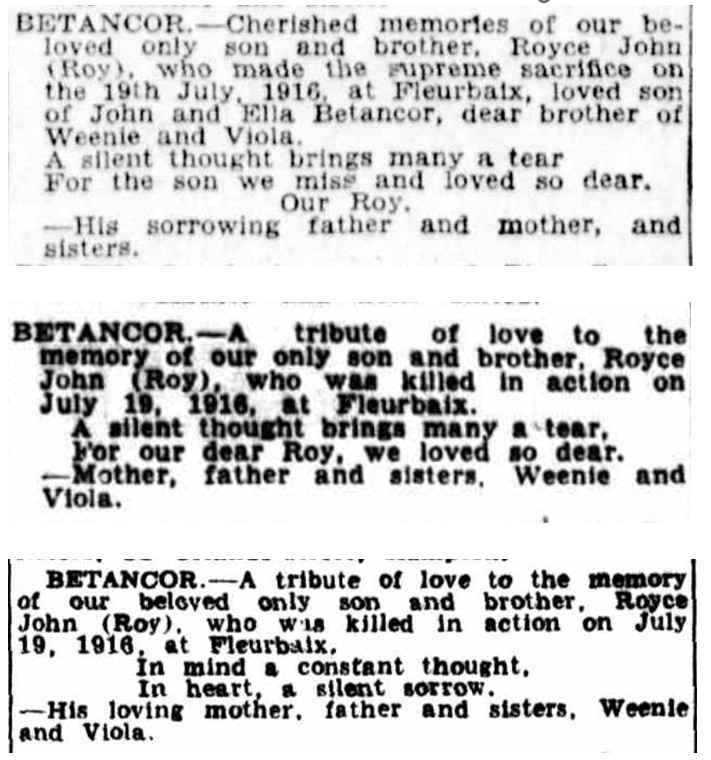

Roy was fondly remembered by his family, who regularly posted memorial notices in the papers for more than 20 years after his death.

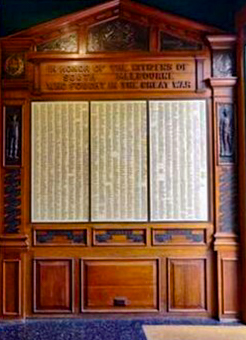

Roy was awarded the 1914–15 Star, the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll. He is commemorated at:

- VC Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial, Fromelles, France (Map Reference MR 7)

- Panel 169, Australian War Memorial, Canberra

- South Melbourne Great Wall Roll of Honour

Family Reflections – Megan Stuart

Roy was my paternal grandmother’s cousin. It is only in the last five years that I found any information about Royce Betancor while researching my family tree. In 2008 I was in France and went to Amiens, La Boiselle, Pozieres, Thiepval, Longueval and Villers Bretonneux as we joined a day tour of the battle grounds of the Somme and visited trenches, memorials and cemeteries.

Both my grandfathers had fought in the Somme and luckily survived and came home. All branches of my family tree lost young men, many who lied about their age and went on what they thought would be an adventure.

I remember that this was a tremendously solemn day of my journey and I wrote in my journal – “What a horrible ending for so many lives, what a senseless waste of life – what have we learnt?’

I was staying in a hotel a few kilometres from Amiens and met some Australians who were working on a project at Hamel. The local French were very friendly when they discovered we were Australians – the same sentiments that Roy expressed.

Royce was the only adult grandson of Manuel and Agnes’ who carried the name of Betancor, so the name died with Royce. Even though I never knew Royce’s close relatives, I can feel their loss of a young man in the prime of his life studying to be a dental mechanic, while enjoying his rowing activities with his mates. What was worse was the fact that he was declared missing in action and the family would have held on to the hope that he had somehow survived and would walk in the door one day and give them a hug.

Finding Roy

Roy’s remains were not recovered, he has no known grave. After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including two of the 315 unidentified soldiers from the 60th Battalion.

While Roy was reportedly buried in a shell hole by a mate a good distance from the Pheasant Wood burial pit location, we still welcome all branches of Roy’s family to come forward to donate DNA to possibly help with his identification, especially those from South Melbourne, Lancashire UK, Ballyvalough, County Antrim Ireland and the Azores/Portugal. If you know anything of family contacts, please contact the Fromelles Association.

We hope that one day Roy will be named and honoured with a known grave. Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Roy’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | John Royce Betancor (1892 – 1916) |

| Parents | John Francis Betancor (1870–1941), Victoria and Ella Alice Stewart Green (1874–1951), Victoria |

| Siblings | Agnes Ella May Betancor (1894–1981), Victoria, m Gordon Veitch | ||

| Viola Dorothy Betancor (1902–1977), Victoria, m Edward Byrne |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Emanuel Jenkin Betancor born Azores/Portugal (1830–1881) and Agnes Jane McKill (1838–1924), Emerald Hill, Victoria | ||

| Maternal | Thomas Green (1847–1918) b Lancashire, and Agnes Jane Blair (1849–1923) b County Antrim Ireland |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).