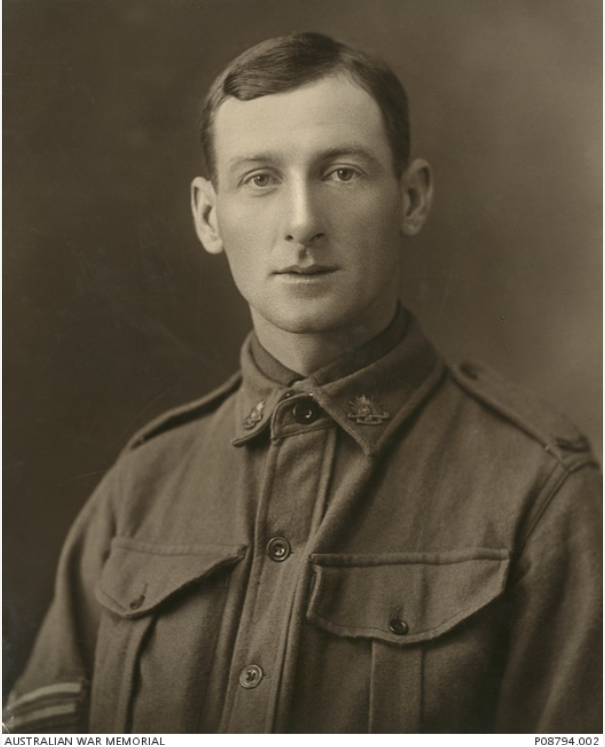

Charles William JOHNSTON

Eyes hazel, Hair fair, Complexion fresh

Charles William Johnston – One of Two Brothers Who Never Came Home

Can you help find Charles?

Charles Johnston’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

Charles may be among these remaining unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in especially those with roots in Sydney, NSW.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for Charles, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Early Life

Charles William Johnston was born in 1892 in Redfern, Sydney, New South Wales, the second son of Arthur Johnston and Anna Maria Beaton. His arrival came at a time when Sydney was rapidly expanding, with Redfern a bustling suburb of workers, tradesmen, and new families. The Johnstons had strong ties to both the city and the country. For a time they lived at Kangaloon in the Southern Highlands, where the cool climate and rolling farmland offered a quieter life.

Eventually, the family settled in Dulwich Hill in Sydney’s inner west, at what would later become their long-term home at 38 Ness Avenue. It was a large family, Charles had eight siblings:

- Francis “Frank” Barclay Johnston (1890–1916) – clerk; served with the 53rd Battalion; killed in action on 25 October 1916 in France.

- Arthur Aughrium Johnston (1894–1970) – served with the 1st Battalion; returned to Australia in 1916; married Alice Elizabeth Bourke.

- Margaret Agnes Johnston (1897–1983) – married Iver Andrew Pederson.

- Mabel Johnston (1899–1978) – married Ernest Frederick Ball.

- Myra Victoria Johnston (1901–1985) – married Albert Symonds.

- Lily May Johnston (1904–1963) – married Raymond Richardson.

- George Edward Johnston (1906–1959) – later served in the Second World War with the 30 Employment Company; married Janet Robertson.

- Robert W. Johnston (1909–1910) – died in infancy.

After his early schooling, Charles contined his studies at the Teachers’ Training College in Sydney, preparing for a career in education. The mid-1910’s were an extremely difficult time for the Johnston household. Charles’ mother, Anna Maria, died in 1913 at 42 years old, leaving his father Arthur to raise their younger children while also managing the older boys’ ambitions for work and service.

Then, the outbreak of the First World War would soon draw three of the Johnston sons into the Australian Imperial Force – Charles and Frank were killed while in the Somme in July 1916 and October 1916. Arthur had joined in 1914 and was headed to Egypt and Gallipoli. He returned to Australia in March 1916.

Off to War

On 31 July 1915, Charles travelled to Warwick Farm to enlist in the Australian Imperial Force. He was posted to the 6th Reinforcements of the 20th Battalion and began training at the Liverpool Camp.

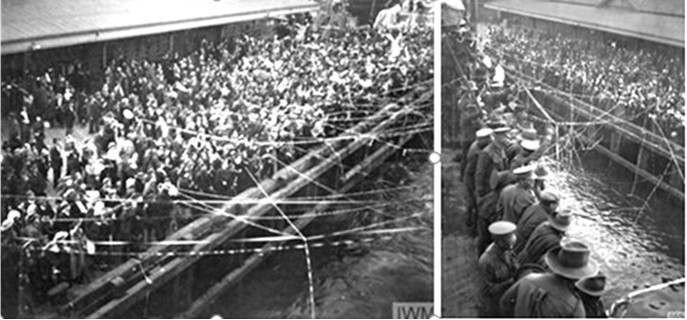

Just over three months later, on 2 November 1915, he embarked from Sydney aboard HMAT A14 Euripides bound for Egypt.

With the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five, major reorganisations in Egypt were underway. The 56th Battalion was raised on 14 February 1916 at the training camp at Tel-el-Kebir, which was about 110 km northeast of Cairo. The 40,000 men in the camp were comprised of Gallipoli veterans and the thousands of reinforcements arriving regularly from Australia. Half of the 56th were Gallipoli veterans from the 4th Battalion and the other half were fresh reinforcements from Australia.

Reflecting the composition of the 4th, the 56th was predominantly composed of men from New South Wales. There would be many challenges in organizing them into an effective fighting unit however, as on 17 Feb they were described as being “a mixed lot and very raw”.

Source: AWM4 23/71/1, 56th Battalion War Diaries, February 1916, page 6.

On 22 March, H.R.H. the Prince of Wales visited the troops and he was greeted with “enthusiastic cheers”. Source - AWM4 23/71/2, 54th Battalion War Diaries, March 1916, page 13

At the end of March they began to move towards Ferry Post at the Suez Canal, a three day, 60 km walk. It was a significant challenge, marching over the soft sand in the 38°C heat with each man carrying their own possessions and 120 rounds of ammunition. Many of the men suffered heat stroke.

Their training continued At Ferry Post, as well as guarding the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army. By the end of April it was noted in the War Diaries that - “A very great improvement is now noticeable in the men’s work.”

Source: AWM4 23/73/3, 56th Battalion War Diaries, April 1916, page 3.

The soldiers were at Ferry Post and the Duntroon Plateau until mid-June. It was not all work however; they did get to swim in the Suez Canal and there was a Brigade sports day held on 10 June. Soon after the sports day, orders to move to the Western Front were received and on 20 June, 990 soldiers of the 56th embarked from Alexandria on HMTHuntsend, headed for Marseilles. They did spend some time enroute at Malta before arriving in Marseilles on 29 June. All were then immediately entrained for a 60+ hour train trip to their camp at Thiennes, 30 km from Fleurbaix in northern France.

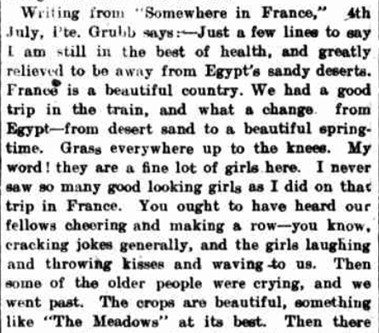

Harry Grubb (2678, 56th Battalion) summed up his experiences to date in a letter he wrote home soon after having arrived in France - “in the best of health, and greatly relieved to be away from Egypt’s sandy deserts”. He signed off asking that he be remembered to all old friends.

This area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. The Battalion then moved on to Estaires, just 10 km from the trenches. Training continued now with gas helmet practice, Lewis Gun training and route marches.

The last leg of their trip was on 12 July and the 56th were into trenches for the first time. They were immediately subjected to artillery shelling and a gas alert. The spent the next three days there before being relieved. Orders were issued for the main attack on the 17th, but it was postponed due to the weather.

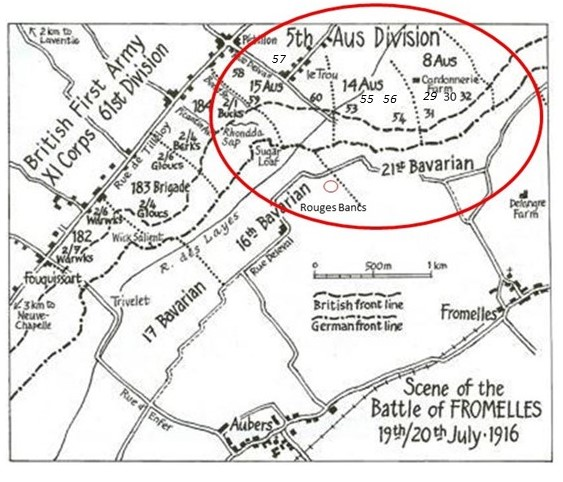

The Battle of Fromelles

On 19 July, the battle began. The main objective for the 14th Brigade was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the Australians would be subjected to murderous enfilade fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 31st and 60th Battalions. The 56th’s role was to provide support for the attacking 53rd and 54th Battalions by digging trenches and providing carrying parties for supplies and ammunition.

They would be called in as the ‘fourth battalion’ if needed for the fighting. Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties.

The 53rd and 54th went on the offensive from 5.43 PM. They did not immediately charge the German lines, but went out into No-Man’s-Land and laid down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift. At 6.00 PM the German lines were rushed. There was heavy artillery, machine gun and rifle fire, but they were able to advance rapidly. Some of the advanced trenches were just water filled ditches, which needed to be fortified to be able to hold their advanced position against future attacks.

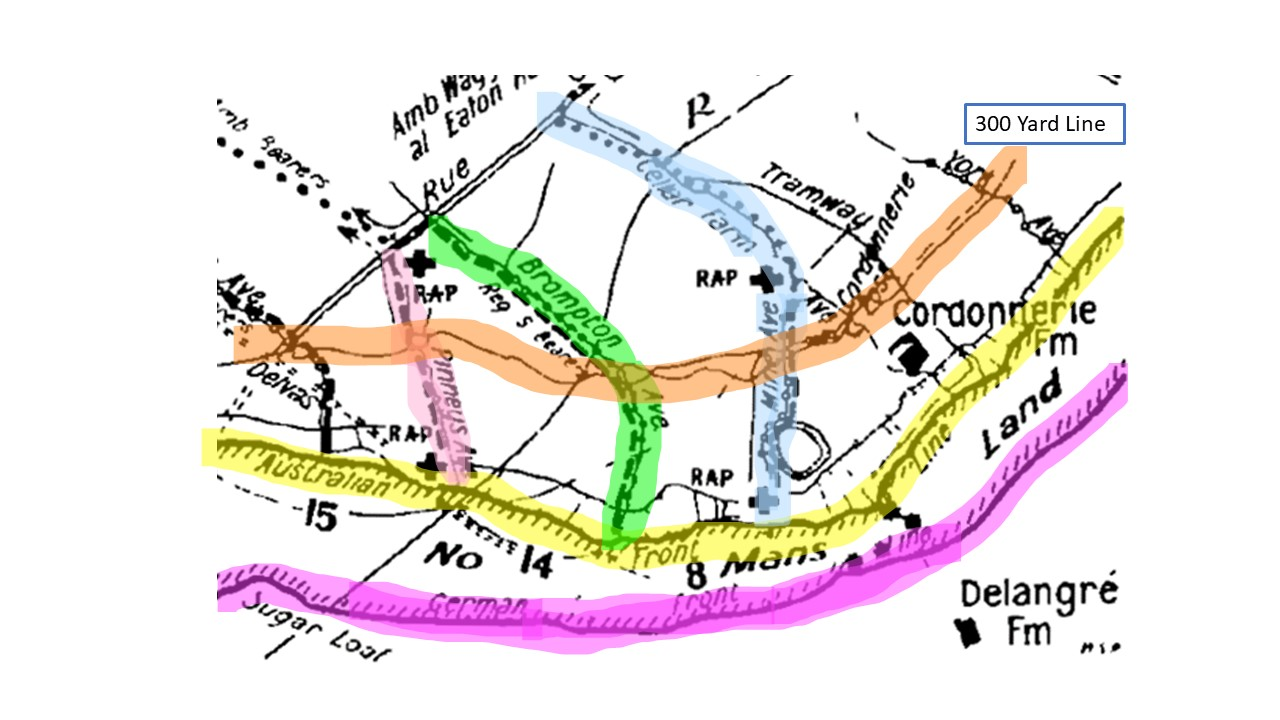

The 53rd and 54th were able to link up with the 31st and 32nd, occupying a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm, but the 60th on their right had been unable to advance due to the devastation from the machine gun emplacement at the Sugar Loaf. At 8.00 PM A and B Companies of the 56th were called to be in position at the 300 yard line between the communication trenches in the Brompton Ave and Milne Ave areas. Heavy shelling of this area was underway. At 9.15 they advanced to the front-line trenches.

While in position at the front trench, very specific orders were received “to the effect that on no account whatever were these two Companies to leave the original front line trenches.”

Source: AWM4 23/14/4 14th Brigade July 1916 page 109.

At 11.00 PM, B Company was called upon to dig a trench to the advance trenches, which they completed by 3.00 AM. It was duck-boarded and it greatly facilitated the movement of munitions to the attacking battalions as well as enabling the saving of “numerous lives” during the retirement of the troops the next morning. The Unit diary notes proudly “that it was the only trench in the Division, to be dug across “No man’s land”” – and this was achieved whilst under fire. Source: AWM4 23/73/6, 56th Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 9.

The attacking battalions held their lines through the night against “violent” attacks from the Germans from the front, but their exposed right flank had allowed the Germans access to the first line trench BEHIND them, requiring the Australians to later have to fight their way back to their own lines. At 5.00 AM on the 20th, C & D Companies were moved forward to the 300 yard line. By 5.50 AM they had moved to the front lines to provide support for the retiring troops and to protect against German counterattacks. The German artillery was being directed at them, “great gaps were blown in the 300 yds line trench.”

Source: AWM4 23/73/6, 56th Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 10.

By 9.00 AM orders were received for the Brigade to retreat from positions won, but a number of the 56th B Company men went forward to help their mates against the German grenade attacks. Shortly after this, A, B & C Companies were called back to garrison the Brigade HQ. D Company remained at the 300 yard line as reserves, if needed. By 9.30 AM the Brigade had “retired with very heavy loss”.

Source: AWM4 23/14/4 14th Brigade July 1916 page 7.

All other Units were out of the trenches by 11.00 AM and collection of the wounded in the trenches continued in earnest. The artillery finally ceased at noon. As no ceasefire was called after the battle, recovery of the wounded that remained on the battlefield was risky. During the next two nights, the 56th recovered over 100 wounded soldiers from No-Man’s-Land. The 56th were then relieved and by 10.00PM on the 21st they were in billets in Bac St Maur, 4 km from the front. F

or a battalion that was to be in reserve as the ‘fourth battalion’, the initial count at roll call was 12 killed, 77 wounded and 13 missing. Ultimately the impact was that 51 soldiers were killed or died from wounds. Of this total, 8 remain missing/unidentified.

Charles’ Fate

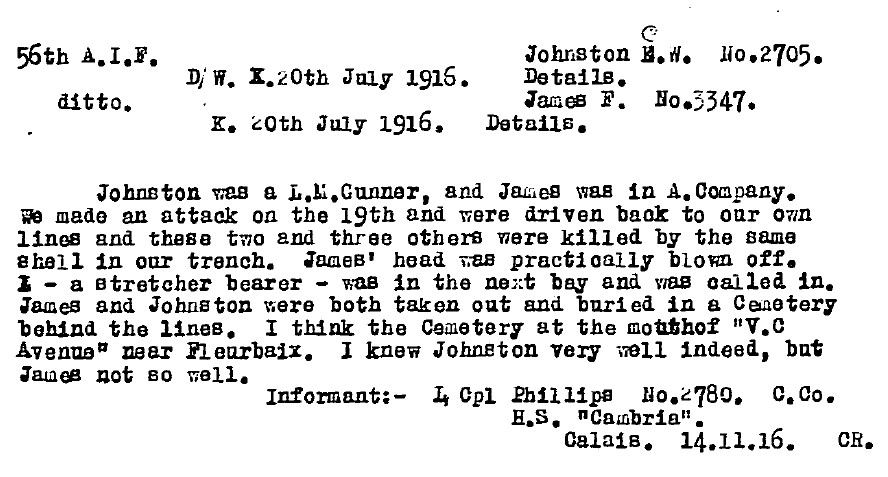

Charles was serving as a Lewis Machine Gunner and was among those in the trenches when heavy shellfire struck late on the 19th. Stretcher bearer Lance Corporal Bertram Henry Phillips (2780), who had joined the AIF in the same reinforcements as Charles, told the Red Cross in November -

One of the men killed beside Charles that night, Private Frederick James (3347, 56th Battalion), was positively identified through DNA testing and reburied with full military honours at Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery in 2010. Another mate, Private Victor Clyde Giles (322), confirmed Charles having been killed, but his 7 December description may explain why Charles’ body was never found:

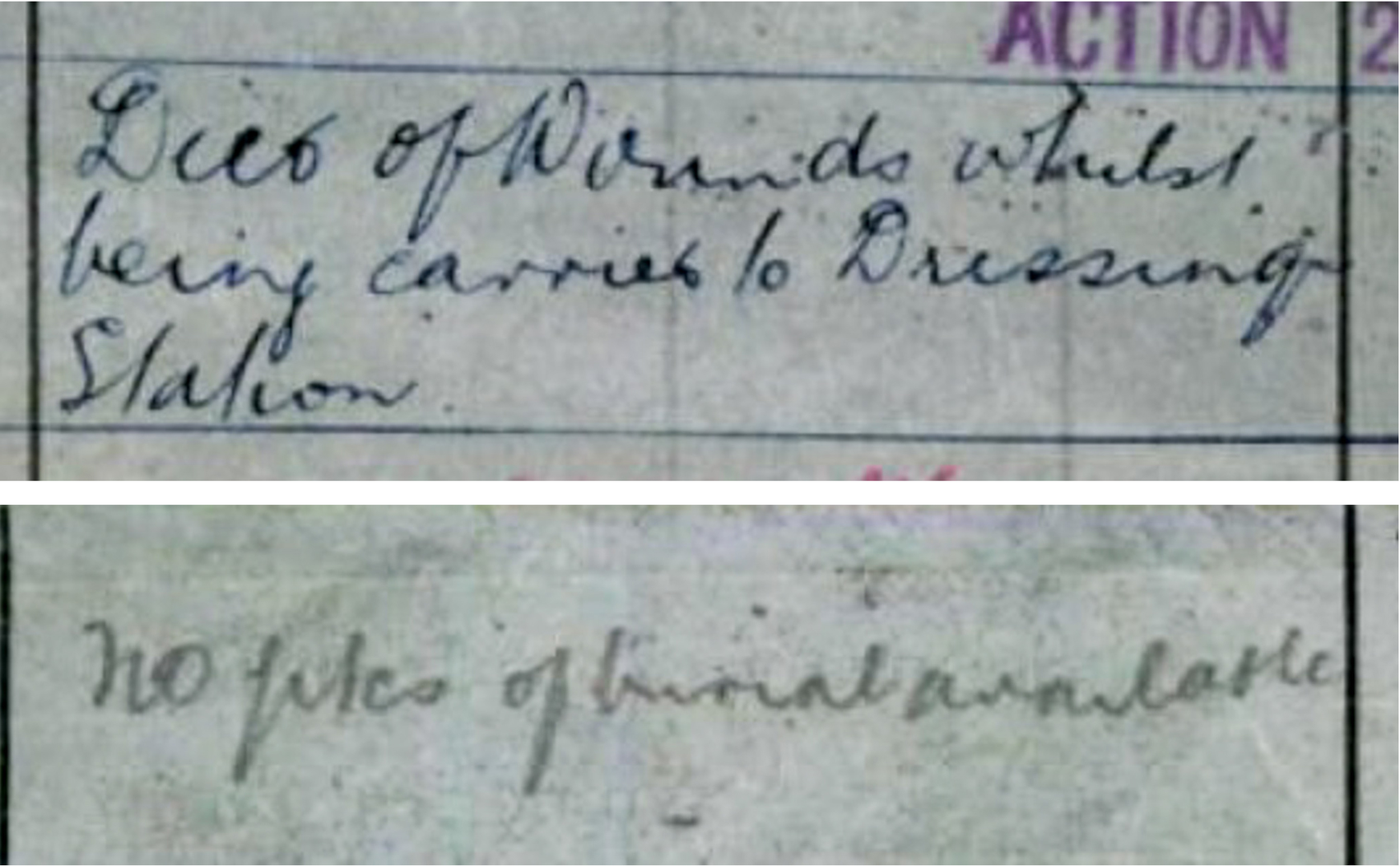

“I knew him well, being in the same lot as he was in the machine guns. He got wounded by a piece of shrapnel in the shoulder in the trenches and while being taken to the dressing station by the (???) they were all blown to pieces by a shell.”

Charles’ Army records cite him as dying of wounds while being carried to the Dressing Station buried, but there are no details on a burial. He remains unidentified to this day.

The Family After the Battle

Soon after the battle, the family received a 28 July letter from Captain A. Chappell advising that Charles had been wounded. However, as more details came to light in November and December, Charles’ death was confirmed, though there still were unanswered questions. To add to the family’s grief, their eldest son Frank had also been killed on 25 October in operations in Flers, south of Fromelles. Charles’ family were desperately searching for answers after being advised of Charles’ death.

As written in an 8 December Red Cross letter:

“in face of this evidence (i.e. the 28 July letter that he was wounded) they naturally cannot bring themselves to believe he died on the 20th.”

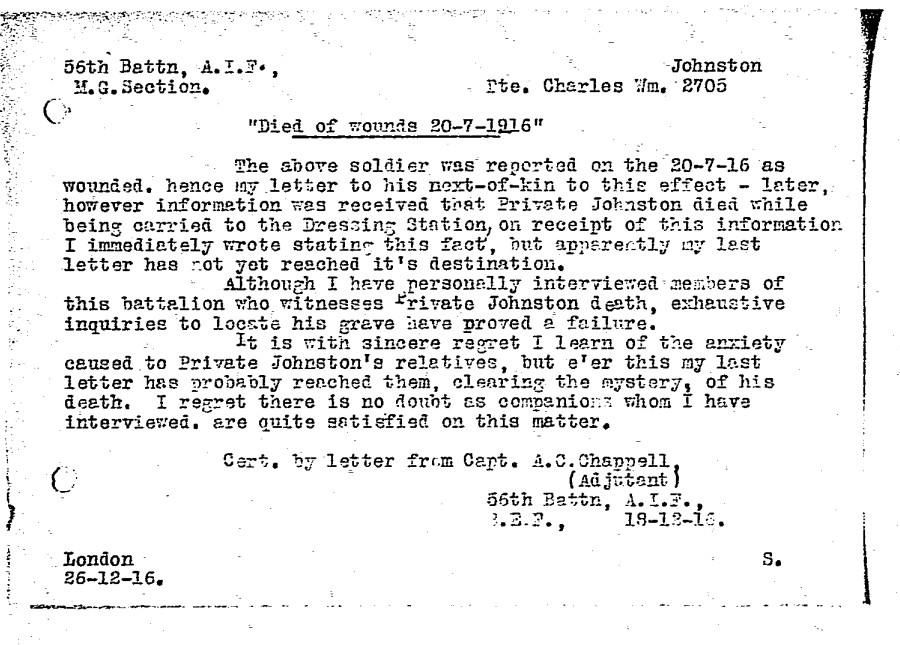

This was brought to the attention of Captain Chappell and wrote to the family with his sincere regrets -

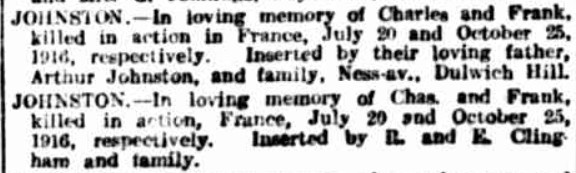

Charles’ and Frank’s deaths were deeply felt by his family and the Dulwich Hill community. Notices for Charles and Frank appeared in the press in July 1917.

Friends and family would later remember Charles as:

“a great favourite with all who knew him.”

Charles is commemorated at:

- VC Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial, Fromelles, France

- Australian War Memorial, Canberra – Roll of Honour, Panel 159

- Sydney Technical High School First World War Honour Roll, Bexley

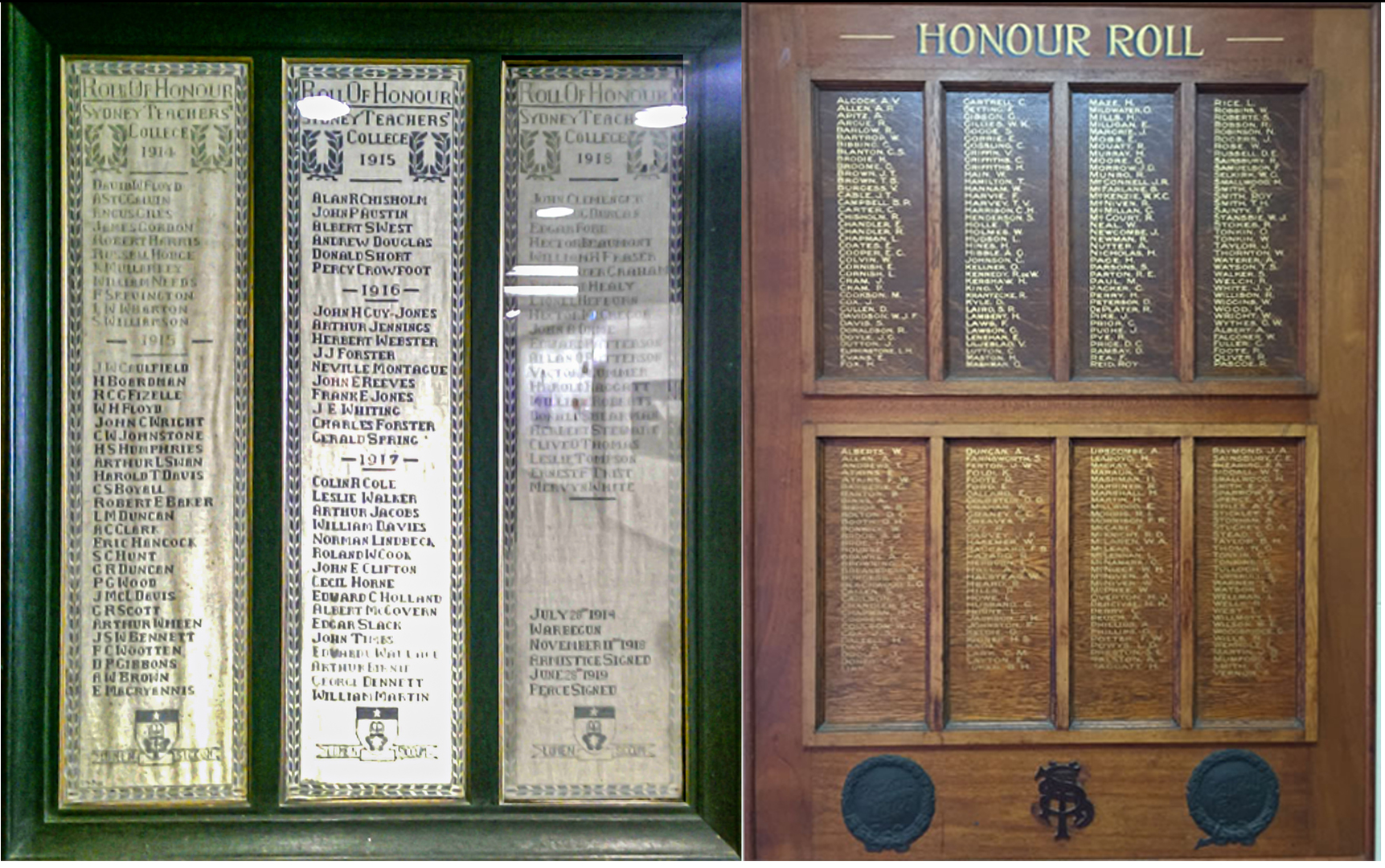

- Sydney Teachers’ College First World War Roll of Honour, University of Sydney, Camperdown

R - Sydney Technical High School Roll of Honour - Frank 6th Panel

Family at War

Arthur had been the first to enlist, in 1914. He served in the 1st Battalion and was assigned as a groom for horses while in Egypt and he was headed for Gallipoli. However, as the horses could not be landed, he returned to Egypt. Following an illness in Egypt, he was sent home in March 1916. Frank had enlisted in December 1915 and arrived in Europe in early June 1916. Following an illness that hospitalised him in England, he was assigned to the 53rd Battalion and arrived in France on 9 October. On 25 October 1916, during operations near Flers in the Somme, Frank was killed in action.

Reports indicate he was leading his men forward under heavy artillery and machine-gun fire when he fell. His body was also never recovered compounding the grief of their parents and siblings. He is commemorated on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial in France.

Their youngest brother, George, was too young for WW1, but he served in the Second World War, enlisting in 1942 until his discharge in December 1945. The family’s wartime losses extended beyond the immediate household.

Their cousin, Private Wilfred Francis Howard Denniss of the 2nd Battalion, was killed in action on 4 October 1917 during the Battle of Broodseinde in Belgium and has no known grave. He is commemorated on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial. Wilfred’s brother Sydney also served in the 1st Battalion. He was wounded in action with a gunshot wound to the arm between 22–25 July 1916, before being returned to Australia.

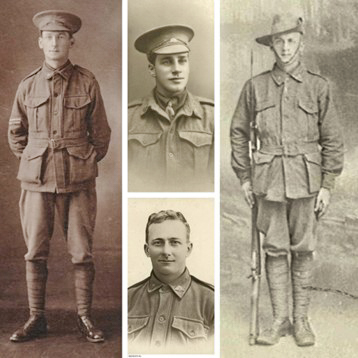

Frank Johnston (left), Wilfred Denniss (top), Charles Johnston (bottom) and Stanley Denniss (right)

Wilfred’s Roll of Honour entry at the Australian War Memorial poignantly records the names of his cousins Charles and Frank, underlining the heavy toll borne by the extended family.

Between Gallipoli, Fromelles, the Somme and the battlefields of Belgium, the Johnston and Denniss families contributed — and in several cases, sacrificed — multiple sons to the war effort. Their story reflects the profound impact of the First World War on Australian families, where the service of one son was often echoed by the service or loss of brothers, cousins, and uncles, across more than one conflict.

Finding Charles

After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified. One of the men in Bertram Phillips’ witness statement, Private Frederick James (3347), was next to Charles in the battle and Frederick James was positively identified at Pheasant Wood through DNA testing in 2010.

While there are questions around the details of Charles’ fate, this identification may give some hope that Charles could be found among the still-unidentified men from the battle. We welcome all branches of Charles’ family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification. If you know anything of family contacts, please contact the Fromelles Association.

We hope that one day Charles will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Charles’ story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Charles William Johnston (1892–1916) |

| Parents | Arthur Johnston (1857–1947, born Sydney, New South Wales) and Anna Maria Beaton (1871–1913, born Newtown, New South Wales) |

| Siblings | Francis Barclay Johnston (1890–1916) – unmarried | ||

| Arthur Aughrium Johnston (1894–1970) – married Alice Elizabeth Bourke | |||

| Margaret Agnes Johnston (1897–1983) – married Iver Andrew Pederson | |||

| Mabel Johnston (1899–1978) – married Ernest Frederick Ball | |||

| Myra Victoria Johnston (1901–1985) – married Albert Symonds | |||

| Lily May Johnston (1904–1963) – married Raymond Richardson | |||

| George Edward Johnston (1906–1959) – married Janet Robertson | |||

| Robert W. Johnston (1909–1910) – died in infancy |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Francis "Frank" James Johnston (1825–1883, born County Fermanagh, Ireland) and Margaret Barclay (1836–1929, born County Tyrone, Ireland) | ||

| Maternal | Christian Carl (Charles) Eduard Bloch (Black) (1846–1923, born Lemvig, Ringkobing, Denmark) and Agnes Beaton (1837–1911, born Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland) |

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).