George Ernest STATHAM

Eyes blue, Hair brown, Complexion ruddy

George Statham - “Harefield, England to Chinchilla, Queensland.”

We thank David Richings and the Harefield History Society for excerpts from David’s book, One Family’s War via their 2022 newsletter, http://www.icsc-uk.co.uk/hhs-newsletter-12.pdf

Can you help us identify George?

Buried near the front line trench…

George was killed in Action at Fromelles. As part of the 31st Battalion he was positioned near where the Germans collected soldiers who were later buried at Pheasant Wood. There is a chance he might be identified, but we need help. We are still searching for suitable family DNA donors.

In 2008 a mass grave was found at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 (Australian) bodies they recovered after the battle.

If you know anything of contacts here in Australia or his relatives from Harefield, Middlesex, England, please contact the Fromelles Association.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

Early Life

In 1871, George’s parents, William and Elizabeth Statham (née Allit), settled in Hill End, Harefield, Middlesex. They raised ten children — five sons and five daughters — in a small cottage community above the lime kilns. George was the eighth child, born in 1885.The children of William and Elizabeth Statham were:

- Alice Elizabeth (1872–1969)

- Walter William (1874–1957) – Regimental Sergeant Major, Royal Field Artillery

- Florence (b. 1875, d. infancy)

- Rose Edith (1876–1898)

- Minnie Selina (1878–1966) – married Arthur Hawkes

- William Henry (1882–1937) – Company Sergeant Major, Royal Field Artillery

- Maude Ellen (1884–1973) – married Ernest Richings

- George Ernest (1885–1916) – AIF, killed at Fromelles, missing

- Thomas Allitt (1889–1982) – Royal Engineers, married Emily Richings

- Albert Arthur (1891–1916) – Royal Fusiliers, killed at the Somme, missing

The Statham sons would all serve in the First World War. Walter and William both served in the Royal Field Artillery, Thomas joined the Royal Engineers, and Albert enlisted in the Royal Fusiliers. Only George came from Australia. The 1891 English Census shows the family living at 71 Hill End, Harefield, with their father working as a carter. By 1901, only the younger sons remained at home. George was a labourer, and by 1911 he was still living with his widowed mother, working alongside his brothers.

Elizabeth Statham was a well-respected figure in Harefield. She lived in the family cottage at Hill End for over 60 years until her death in 1932 and was a subscribing member of the Victoria Court of the Ancient Order of Foresters, a local friendly society that provided mutual aid to its members. Her involvement began as early as 1864, and she remained active in the group well into her later years — a reflection of her deep ties to the village and its people.

George is believed to have worked for the Great Western and Central Railway, helping build the branch line from Uxbridge to Denham. He was later found on the passenger list of the SS Kaipara, departing for Brisbane, Queensland in May 1911. He had responded to a large recruitment drive for workers to build railway lines in Australia. That journey brought George to outback Queensland, where he worked in Chinchilla — possibly cutting timber for narrow-gauge railway sleepers in the Barakula State Forest.

A Family at War

The Stathams of Harefield made an extraordinary contribution to the war effort. Widowed matriarch Elizabeth Statham saw all five of her sons enlist in the First World War — four served in the British Army, and one, George, enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force after emigrating to Queensland. Their service tells a powerful story of loyalty, loss, and endurance, stretching from the trenches of France to the timber camps of outback Australia.

Walter William Statham (b. 1874) was the eldest son. Already a Regimental Sergeant Major in the Royal Field Artillery at the outbreak of war, he remained in service until 1917, when he was discharged due to ill health. In 1919, he married Beatrice Hookham, the widow of another soldier, and settled in Northwood Road, Harefield. A newspaper clipping from the Uxbridge & W. Drayton Gazette, dated 12 July 1918:

The appeal of W. Statham, 43, Grade II, single, labourer, of Harefield, on the grounds that he was the only son left at home to look after a widowed mother, was dismissed. Two of his brothers have been killed, and two others are still on active service.

William Henry Statham (1882–1937) enlisted in the British Army in 1900 and served twelve years in India. When war broke out in 1914, he was deployed to the Western Front with the Royal Field Artillery and served throughout the Great War. He was discharged in 1919 due to disability. His service record was destroyed in the Blitz. According to his obituary in the Uxbridge & West Drayton Gazette, he returned home and ran a small poultry farm at “The Shrubs” in Harefield, where he was well known.

He remained unmarried and lived with his widowed mother Elizabeth until her death in 1931. William died on 1 November 1937, aged 55, after several years of declining health. At his funeral, his brothers Walter and Thomas and sisters Minnie (Mrs Hawkes) and Maude (Mrs Richings) were listed among the mourners.

Source: Find my past, Uxbridge & West Drayton Gazette, 12 November 1937

George Ernest Statham (b. 1885) was the only son to emigrate. He arrived in Queensland in 1911, working on railway construction near Chinchilla. He enlisted in the AIF in 1915, joining the 31st Battalion. George was killed in action at Fromelles on 20 July 1916. His body was never recovered.

Thomas Allitt Statham (b. 1889) joined the Royal Engineers in 1914. He was deployed to France in 1915 and promoted to Corporal. In 1918, while on leave, he married Emily Richings, and after the war they settled back in Harefield.

Albert Arthur Statham (b. 1891) worked at the Bells United Asbestos Factory in Harefield before enlisting in the Royal Fusiliers. He served on the Western Front from 1915 and was killed in action on 8 July 1916 during the opening days of the Battle of the Somme. Like George, his body was never found, and he is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial.

Of the five brothers, two — George and Albert — were killed in action within days of each other in July 1916, in separate battles on the Western Front. Their mother Elizabeth endured the devastating loss of two sons while three others were still in uniform. In later years, George’s sister Maude often spoke to her grandson David Richings of how deeply the family mourned — and how proud they were of all five sons’ service.

The Statham family’s sacrifice is a powerful reminder of the far-reaching impact of the war — not just on one nation, but on families that bridged the world.

Off to War

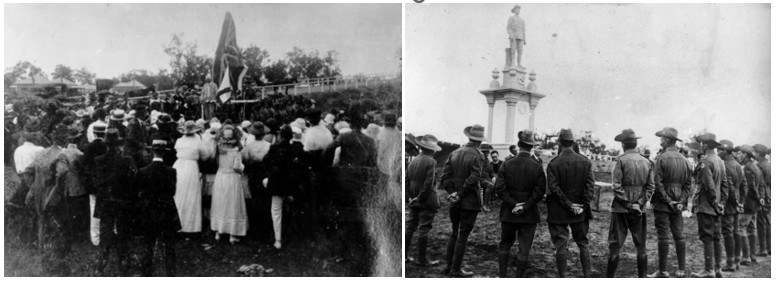

George enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force on 11 August 1915 at Toowoomba, Queensland, joining A Company of the newly formed 31st Battalion. This battalion was composed of two companies from Queensland and two from Victoria, with George among the Queenslanders who began their training at the Rifle Range Camp at Enoggera, near Brisbane. In October 1915, the full battalion assembled at Broadmeadows Camp in Victoria for final training.

Before embarkation, they paraded through the streets of Melbourne to cheering crowds. Minister for Defence H.F. Pearce told the press:

"I do not think I have ever seen a finer body of men."

Source: INFANTRY MARCH PAST (1915, November 6). Weekly Times (Melbourne), p. 32. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article132708935

Their chance would come soon. In mid-June 1916, the battalion was ordered to prepare for transfer to the Western Front. As the date of departure approached, George wrote home from Broadmeadows Camp on 10 October 1915. His letter to his mother, Elizabeth, was full of concern for her welfare and hints of quiet resolve:

METHODIST SOLDIERS’ TENT

Military Camp, Broadmeadows

Oct 10th, 1915

Dear Mother,

Hoping this will find you all well as it leaves me well in the best of health at present dear mother I am to be shifted from Broadmeadows to Melbourne in Victoria ready to go to the front I expect by the time you get this letter I shall be on the way over there I hear we are going on the 18th October

Dear mother I have by this time got my National deposit book everything is correct I have now £14.10.5 in the bank got from the government have 13.14 pounds in the book and if I get killed as you have to send the number of my bank book it is 190344 on it to the pay master of the Commonwealth government in the Army and if I get killed you will get it in a lump sum if I am not killed you will get the 4 shillings per day as I agreed to send back to the Commonwealth every week so you can sometimes send to the pay master if you are in need of anything make sure to keep this number of my book and if you are in want of anything keep it so you can get it

Mother dear I am not far from the time now I will be going to the front we may be going any time I hope it will soon be over mother dear I know you think of me all the time if I don’t come home dear mother I think this is all to say this time I hope you are all right with your leg as I know you are suffering a bit with it I will now draw to a close

Dear hope Tom and Albert are well tell all to remember me to all the lads

From your Loving son George.

On 9 November 1915, George sailed from Melbourne aboard HMAT Wandilla. As the troopship steamed west, some of the Ballarat men in D Company placed notes in bottles and tossed them into the sea as part of a farewell ritual. One such bottle was later found and published in The Ballarat Courier, listing the names of men aboard. George likely watched on, knowing his own message to his mother in England would soon be en route via official channels.

The Wandilla docked at Port Suez on 7 December 1915. The 31st Battalion was sent to Serapeum to continue training and help guard the Suez Canal. By February, they had moved to the large training camp at Tel el Kebir. It was a rough introduction to desert conditions. The battalion’s war diary recorded how the men were transported “in dirty horse trucks,” an experience that tested their patience as much as their endurance.

Source AWM4 23/48/7, 31st Battalion War Diaries, Feb 1916, p. 5

After further moves to Ferry Post and then Moascar near Ismailia, the men grew weary of the sand, heat, and flies. Private Les Smith (934) wrote home:

We’ve had enough of sand and flies. The boys are all keen to get to France and do their bit.

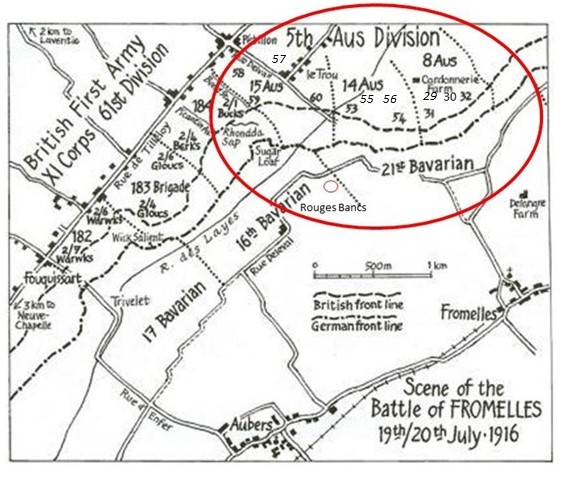

The Battle of Fromelles

On 15 June 1916, the 31st Battalion began its move to the Western Front, travelling by train from Moascar to Alexandria and embarking on the troopships Hororata (for most of the battalion) and Manitou (for C Company). They arrived in Marseilles on 23 June 1916 and continued by train to Steenbecque, then marched to Morbecque, about 35 kilometres from the front at Fleurbaix. By early July, the 31st was receiving instruction in trench warfare. On 11 July, they entered the trenches for the first time, relieving the 15th Battalion near Bois-Grenier.

Over the following days, they adjusted to the realities of life on the Western Front — including night patrols, sniping, gas alerts, and the use of grenades. All of this was in preparation for a large-scale attack planned to divert German attention from the Somme. The original date of the attack was 17 July, but heavy rain caused a delay. By the afternoon of 19 July, the 31st Battalion was in position in the front-line trenches.

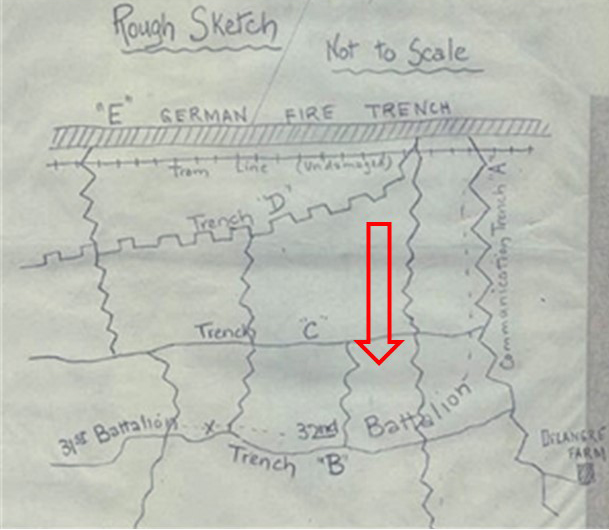

At 5.58 PM, the men launched their assault in four waves, A and C Companies in the first and second waves, followed by B and D Companies in the third and fourth. The preliminary bombardment had damaged the German forward trench, and by 6.30 PM, Australian troops had taken control of the German’s first line system (Trench B), which was described as:

practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom.

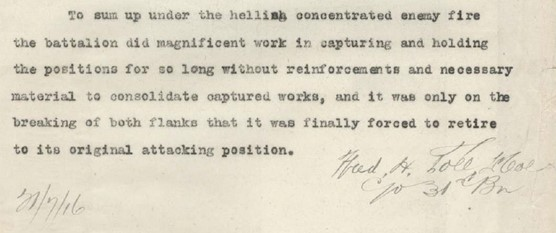

However, this early success turned tragic. Some forward troops were shelled by their own supporting artillery, unaware that Australians had already taken the trenches. Others were exposed to fire from German machine guns positioned behind their advance. By 8.30 PM, the Australian left flank — held by the 32nd Battalion — came under intense bombardment. Orders came through that the trenches were to be held at all costs.

Source AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, p. 12

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made another push toward the German support lines, but they were low on grenades and facing withering machine gun fire from Delangre Farm. Some were so far forward that they began receiving fire from both the German and Australian artillery. At 4.00 AM on 20 July, the Germans began a counterattack from the left flank, retaking parts of the line. With key rear trenches undermanned, the German forces were able to envelop Australian positions.

By 5.30 AM, they attacked from both flanks in force. Lacking grenades and exhausted, the Australians were forced to retreat across No-Man’s-Land under devastating machine gun and artillery fire. One battalion account described it plainly:

The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Man’s Land resembled a shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.

By the evening of 20 July, what remained of the 31st had withdrawn. From the original strength of 1019 soldiers, 77 were confirmed killed or died of wounds, 414 were wounded, and 85 were missing. Later records determined that 166 men from the battalion were killed, with 84 of those missing or unidentified. Australia’s official war historian, Charles Bean, visited the battlefield more than two years later and reported that Australian uniforms, equipment, and bones still lay on the ground.

George was initially reported missing after the attack. A year later, a Court of Enquiry found that he had been killed in action. The following eyewitness statement was provided to the Red Cross by one of his comrades, Sgt. W. Kennard, A Company, 31st Battalion, 5 February 1917:

I saw him killed outright by a shell at Fleurbaix in the charge on 19th July. This happened on the way across, in No Man’s Land. His body was afterwards buried near the front line trench.

George’s AIF file contains a handwritten annotation that corroborates the Red Cross evidence:

Buried in the vicinity of Fleurbaix Sh. 36 N.W.

NAA B2455, STATHAM George Ernest – First AIF Personnel Dossiers, 1914–1920

Several of Georges’s fellow soldiers were later recovered from mass graves at Pheasant Wood and identified through DNA, including men recorded on Sheet 36 NW — the same map reference noted in George’s service file. Soldiers such as Haslem Kendall, Harold Woodman, and Henry Victor Willis, all from the 31st Battalion, were found in this area.

After the Battle

Despite these details, George’s remains were never formally recovered or identified.George’s brother Albert Arthur Statham had been killed only twelve days earlier, on 8 July 1916, in the opening stages of the Battle of the Somme. Their mother, Elizabeth, had already been a widow for 15 years. She never saw either of her sons again. In 1932, Elizabeth passed away in her home at Hill End, Harefield, aged 83. According to her obituary in the Uxbridge & West Drayton Gazette, she had lived in the same cottage for 61 years and was:

one of Harefield’s oldest and most respected residents.

She was buried alongside her husband William, who had died in 1901.Although George has no known grave, his name is inscribed on several memorials that honour his service and sacrifice.

George is commemorated at:

- VC Corner Australian Cemetery Memorial

- Panel 119 of the Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour

- Chinchilla War Memorial in Queensland — the outback town where he had worked before enlisting.

In England, George’s name lives on through the efforts of his family. His great-nephew David Richings has worked tirelessly to share the story of the Statham brothers and their service. David also helped connect a family DNA donor to the Australian Army to support efforts to identify George among the unknown remains recovered from Pheasant Wood in 2008.

David paid tribute to George in 2022 with these words:

GEORGE ERNEST STATHAM

I’m very sorry that I could not make the journey from England to join you today but I’m very glad to have the opportunity to send a message.

These days the Poms and the Aussies are often rivals on the sports fields, but the First World War showed the true extent of the camaraderie between our two nations. Nowhere was that more in evidence than at the Battle of Fromelles.

I speak as a descendent of a young Englishman who was proud to have enlisted in the 31st Infantry Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force at Toowoomba on 11 August 1915.

He was one of the numerous men recruited from England to work as Navvies on the building of the railway infrastructure in Queensland in the early part of the 20th century. He arrived in Brisbane in 1911 on the SS Kaipara and was deployed to work on the construction of the Timber Tramway between Chinchilla and the Barakula State Forest.

When Australia joined the War, and was recruiting men to serve, George didn’t hesitate to volunteer. After a period of training in Egypt, he was posted to the Western Front as part of the Allied forces. Sadly, as was the case with so many brave young men of that generation, his life expectancy was short, and so it proved. Within a few months of his arrival in France, George perished at Fromelles on 20 July 1916, alongside many of his Australian comrades.

George’s body was never found, which was enormously distressing for his family, not least his widowed mother at home in England. She had just lost another son at the Battle of the Somme, and she had three other sons also serving in France. My grandmother – George’s sister - used to tell me how difficult those times were for the family.

As a family historian I have long wondered where George fell, and what became of him. That is why I have such admiration for the work of the Fromelles Association, and the Australian Army, in trying to identify the missing. Although my DNA would not be suitable, I have been able to introduce Major Wilson to one of my female cousins, who is happy to provide her DNA sample to see if George’s remains might be among those discovered at Pheasant Wood and which remain unidentified.

It is comforting to George’s family to know that he is not forgotten, and that his memory is sustained so well by the Australian Army, and the splendid volunteers of the Fromelles Association, who continue with their mission to identify the missing.

Thank you for all you are doing. It really is much appreciated.

In Harefield, where George was born and raised, his family’s story is still remembered today thanks to the work of the Harefield History Society, which has documented the sacrifice of the Statham brothers in community archives and local publications.

Finding George

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | George Ernest Statham (1885–1916), Fromelles |

| Parents | William Statham (1846–1901), Harefield, and Elizabeth Jane Allitt (1848–1932), Middlesex |

| Siblings | Alice Elizabeth (1872–1969) | ||

| Walter William (1874–1957), RSM Royal Field Artillery | |||

| Florence (died in infancy) | |||

| Rose Edith (1876–1898) | |||

| Minnie Selina (1878–1966), married Arthur Hawkes | |||

| William Henry (1882–1937), CSM Royal Field Artillery | |||

| Maude Ellen (1884–1973), married Ernest Richings | |||

| George Ernest (1885–1916), missing Fromelles AIF | |||

| Thomas Allitt (1889–1982), Royal Engineers, married Emily Richings | |||

| Albert Arthur (1891–1916), missing Somme, Royal Fusiliers |

| Grandparents | ||||

| Paternal | George Statham (1812–1868), Hertfordshire and Julia Douglas (1809–1875), Buckinghamshire | |||

| Maternal | Henry Allitt (1810–1858) and Eliza Lawrence (1814–1874), Middlesex |

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).