Charles BANNON

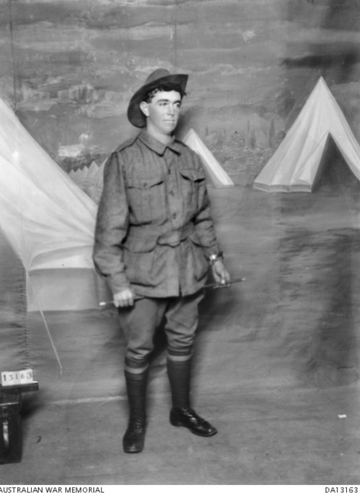

Eyes brown, Hair dark brown, Complexion dark

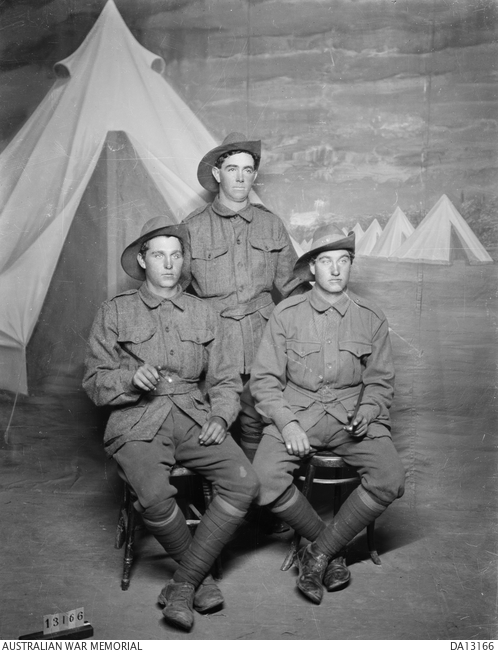

Charlie, Percy and Hughie – Three Terang Mates Who Enlisted Together

Early Life

Charles “Charlie” Bannon was born on 30 January 1892 in Terang, Victoria, the son of Patrick James Bannon and Sarah Ann Wheatley. They had seven children:

- Thomas John (1886–1953)

- William James (1888–1947)

- Ellen Lochlin (1890–1977)

- Charles (1892–1916)

- Catherine Vera (1895–1948)

- Ruby (1901–1975)

- Leslie George (1904–1929)

His mother Sarah’s family were among Terang’s earliest settlers. Charlie’s grandfather, Thomas Wheatley, arrived in the district in 1854 and became the town’s first carrier, hauling goods by bullock team from Warrnambool to Geelong. Charlie attended Terang State School and then became a blacksmith. He did his apprenticeship with A. J. Thomas Coachbuilders in Terang. Ivy Gertrude Wright and her mother and sisters moved to Terang for work in 1909 and she met Charlie there. Their relationship grew quickly and when Ivy returned to Geelong, Charlie visited whenever leave or work allowed.

The two were married on 22 August 1915 in Geelong, just months after Charlie enlisted and shortly after the birth of their daughter Margaret, who became the centre of Ivy’s world while Charlie prepared to sail for war.

Off to War

Charlie was 22 and working as a blacksmith in Terang when war broke out. His closest friends were the Baker brothers — Percy and Hughie — sons of a well-known local family whose father was also a blacksmith. Recruiting in the area had gathered momentum following a public meeting in June 1915 and the enlistees names were published in the Terang Express soon after. Among them were Percy and Hughie and Charlie. Recollections on the Virtual War Memorial Australia page for Charlie describe how the three young men decided to enlist together:

When Hughie — the younger brother — spoke of joining up, their father Henry is said to have told him, “You’d better take your brother with you to keep an eye on you.” Percy agreed, and their mate Charlie Bannon laughed, “Then I’d better go too, to keep an eye on you both.”

And so the three Terang boys travelled to Melbourne in July 1915 and enlisted almost side by side, their regimental numbers stamped in sequence by the recruiting clerk -3453 (Percy), 3454 (Hughie), and 3456 (Charlie) — confirmed that they enlisted together. They were assigned to the 21st Battalion, 8th Reinforcements.

They did their training at Broadmeadows and Bendigo, writing home when they could, and taking precious opportunities for leave. Charlie visited Ivy and his new daughter Margaret as often as possible. On 29 December 1915, the three mates embarked from Melbourne aboard HMAT A64 Demosthenes with the 8th Reinforcements to the 21st Battalion for the month+ trip to the training camps in Egypt. With the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five, major reorganisations were underway.

All three remained in the 15th Brigade, but Charlie was assigned to the newly formed 60th Battalion Percy and Hughie ended up in the 59th. The 60th Battalion was raised in Egypt on 24 February 1916 at the 40,000-man training camp at Tel-el-Kebir, about 110 km northeast of Cairo. Roughly half of the soldiers were Gallipoli veterans from the 8th Battalion, a predominantly Victorian unit, and the other half were fresh reinforcements from Australia. Their training continued, necessary to build the bonds necessary for the fighting to come. In mid-March they were inspected by H.R.H the Prince of Wales.

After a month of training at the large camp at Tel-el-Kebir, they had a two+ day, 50 km march in thermometer-bursting heat across the Egyptian sands from Tel el Kebir to Ferry Post, near the Suez Canal. Prior to marching, only ½ pint of water per bottle was available.

Source- AWM4 23/15/1 15th Brigade War Diaries Feb-Mar 1916 p 6.

They remained at Ferry Post until 1 June continuing their training and guarding the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army. Their time in Egypt was not all work, however. A 5th Division Sports Championship was held on 14 June, which was won by the boys’15th Brigade. Just afterwards, on 17 June, they received orders to begin the move to the Western Front and were on trains to Alexandria. The majority of the battalion, 30 officers and 948 other ranks, embarked in Alexandria on the transport ship Kinfauns Castle on 18 June 1916.

After a stop in Malta, they disembarked in Marseilles on 29 June and were immediately put on trains, arriving in Steenbecque in northern France, 35 km from Fleurbaix on 2 July. This area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. On the 7th they began their move to the front, arriving in Sailly on the 9th. Now just a few kilometres from the front, their training continued, although with a higher intensity, I’m sure. The move to Fleurbaix continued and the 60th were into the trenches for the first time on 14 July.

The Battle of Fromelles

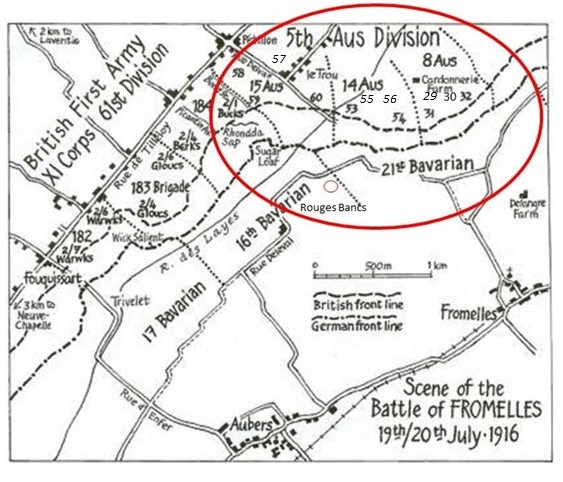

The battle plan had the 15th Brigade located just to the left of the British Army. The 59th and 60th Battalions were to be the lead units for this area of the attack, with the 58th and 57th as the ‘third and fourth’ battalions, in reserve. The main objective for the 15th Brigade was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfilade fire from the machine-guns and counterattacks from that direction.

As they advanced, they were to link up with the 59th battalion and the British on their flanks. The 60th Battalion faced an especially difficult position in the assault, right across from the ‘Sugar Loaf’. The main attack against the Sugar Loaf position was planned for 17 July, but it was delayed due to bad weather. Two days later, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties.

A fellow soldier, Private Bill Boyce (3022, 58th), summed the situation up well:

“What have I let myself in for?”

Their attack on the German lines began at 5.45 PM on the 19th. The 59th went over their parapet in four waves at 5 minute intervals, but then laid down to wait for the support bombardment to end at 6.00 PM. A and B Companies were in the first two waves, and Charlie’s C Company and D Company were in the next two. Percy and Hughie Baker were just to Charlie’s left. There was immediate and intense fire from rifles and the Sugar Loaf machine guns, but Corporal William Holtham (4801), a machine gunner with the battalion, later wrote of the men’s courage as they stepped into the open:

“Not a man flinched, not a single chap hung back when his turn came. They were just up and over.”

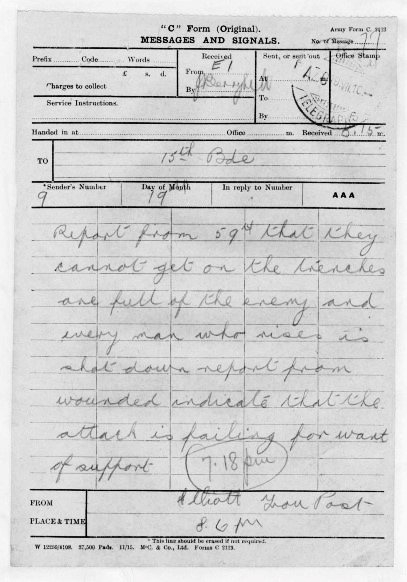

As documented in the messages sent back to HQ just after the attacks began:

“cannot get on the trenches as they are full of the enemy”

“every man who rises is shot down”

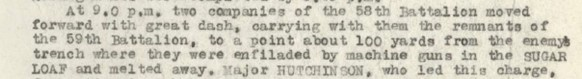

“‘they were enfiladed by machine guns in the Sugar Loaf and melted away”

The British 184th Brigade just to the right of the 59th met with the same resistance, but at 8.00 PM they got orders that no further attacks would take place that night. However, the salient between the troops limited communications, leaving the Australians to continue without British support from their now exposed right flank. The advances against the Sugar Loaf fortification were limited, but it was reported that some got to within 90 yards of the enemy trenches. One soldier said he “believed some few of the battalion entered enemy trenches and that during the night a few stragglers, wounded and unwounded, returned to our trenches.”

Source - AWM4 23/77/6, 60th Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 3.

However, their gains were impossible to hold and with little support being available they had to drop back. With known high casualties in the 60th, they were relieved by the 57th Battalion at 7.00 AM. Roll call was held at 9.30 AM. In the ‘Official History of the War’, Charles Bean said, “of the 60th Battalion, which had gone into the fight with 887 men, only one officer and 106 answered the call.”

Source - Chapter XIII page 442

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The final impact of the battle on the 60th was that 395 soldiers were killed or died of wounds, of which 315 were not able to be identified. The 59th suffered a similar fate. Charlie’s body was recovered from the battlefield, Percy’s was not.

After the Battle

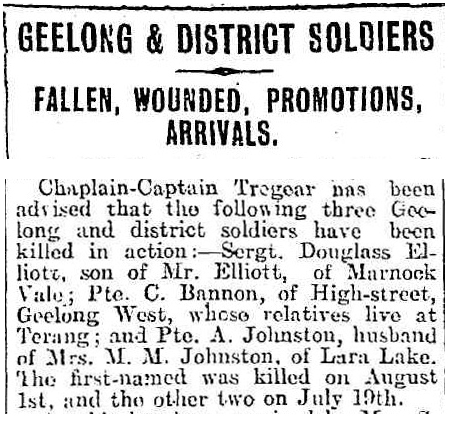

Charlie and Percy were not among those at their unit’s roll calls, but at least Hughie survived. News of his Charlie’s death reached both Terang and Geelong within weeks and Charlie’s young wife Ivy faced the sudden reality of widowhood.

A personal tribute followed soon after in the Terang Express, offering a glimpse into the grief felt by the Bannon family:

In sad but loving remembrance of our dear son, Pte. Charles Bannon, who was killed in action in France on July 19th, 1916.

“The world is wide, the sea is deep,Far o’er the sea our dear Charlie sleeps.He went away in health and strength,For King and Country his time he spent;No sadder news to us could fallThan to hear he answered his last bugle call.”

Inserted by his sorrowing mother, father, sisters and brothers.

Two months after Charlie’s death, Ivy wrote to Base Records from West Geelong, hoping for the return of his personal effects to give her some degree of closure:

“Could you return to me anything belonging to my husband… I know he had a watch, ring, and his kit. Kindly let me know if I shall be able to receive these things.— Mrs Ivy G. Bannon, 14 High Street, West Geelong, 19 September 1916”

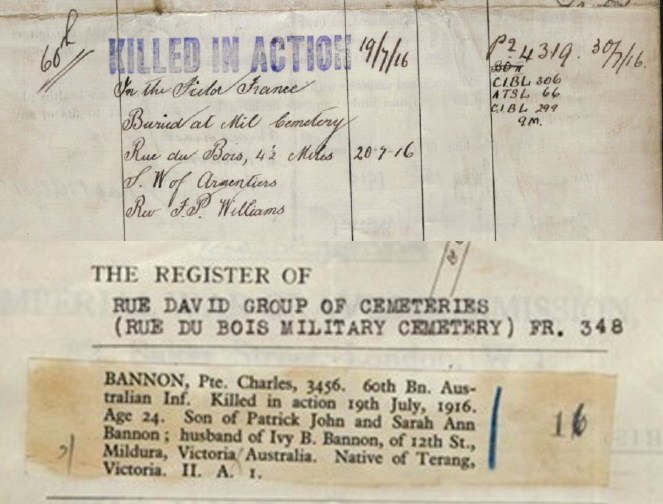

There are no records that show anything of Charlie’s was returned to Ivy. Charlie was buried on 20 July 1916 by Rev. F. P. Williams, who was attached to the 58th Battalion, and he now rests in Rue-du-Bois Military Cemetery, Fleurbaix, Plot II, Row A, Grave 1. Charlie shares this grave with Private Edward Bunn (3311) of the 58th Battalion, another young Victorian soldier who was killed in the same attack at Fromelles on 19 July 1916.

shared with Edwin Bunn

“FOR DUTY DONE

OUR DEAR ONE REMEMBERED”

Charlie Bannon’s name has never faded from the places he called home. In Terang, his birthplace and childhood town, he is remembered on the Terang War Memorial, the Terang Centenary of Armistice “Remembering Our Fallen” honour roll and on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial, Panel 169.

Those Left Behind - Ivy and Margaret Bannon

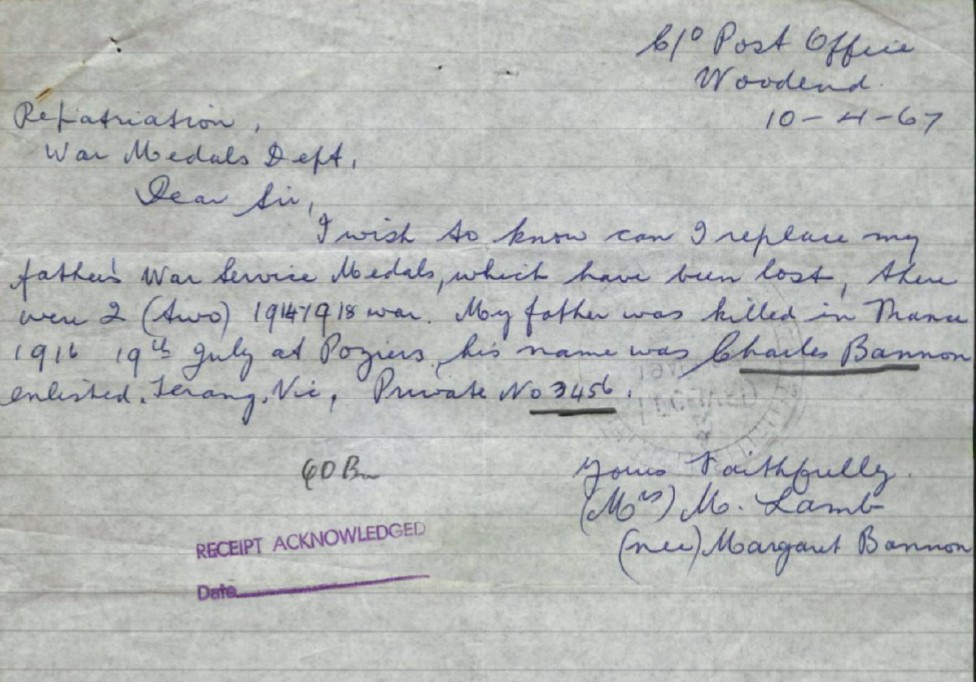

For Ivy and Charlie’s daughter Margaret, Charlie’s loss changed the course of an entire life. Ivy continued on in Geelong, supported by her family. She did remarry, to William Edward Webster in 1919 and they lived together for the next 40 years. Margaret grew up never knowing her father, yet she carried his memory with her. More than fifty years after his death, she reached out to replace his lost medals — a quiet, enduring act of remembrance from a daughter who had held onto her father’s story all her life.

Unfortunately for Margaret, Army protocols did not allow the medals to be reissued. A husband, father, blacksmith and mate to the Baker brothers of Terang, Charlie’s story stands among the many whose lives were cut short in the fields of Fromelles. His legacy continues through his family, his hometown and the community that still speaks his name more than a century later.

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).