Herbert James GRAHAM

Eyes brown, Hair dark brown, Complexion Unknown

Herbert James Graham – “A dauntless lad”

108 years after the Battle of Fromelles, Herbert James Graham has finally been found.

DNA matching from family members has been successful in identifying Herbert as having been buried in the Pheasant Wood grave that had been dug by the Germans.

The 23 April 2024 announcement of seven further soldier identifications brings the total to 180 of the 250 soldiers in the burial site.

.

Herbert James Graham - The Dauntless Lad in a Khaki Suit

Herbert James Graham was born in Dubbo in 1892 to Thomas Albert George Graham and Alice Maria Dulling, the fifth of their six children, three boys and three girls.

Unfortunately, Herbert’s mother passed away when he was just five years old. Thomas remarried in 1906 to Rose Hessler and they had four children. Rose also had four children from her first marriage before her husband died, which brought the total for the combined household to fourteen children!

Herbert was also known as James, as one of her Rose’s sons from her first marriage, also a Herbert (May), was the same age as Herbert James.

Thomas was a farmer and ran cattle. The family lived in the town of Geurie, 28 km from Dubbo. Thomas was highly esteemed in the community and was a preeminent member of the Masonic Lodge and the Manchester Unity Oddfellows’ Lodge. Herbert attended school in Geurie and then worked as a labourer, likely on his father’s or a neighbouring farmer’s land.

Off to War

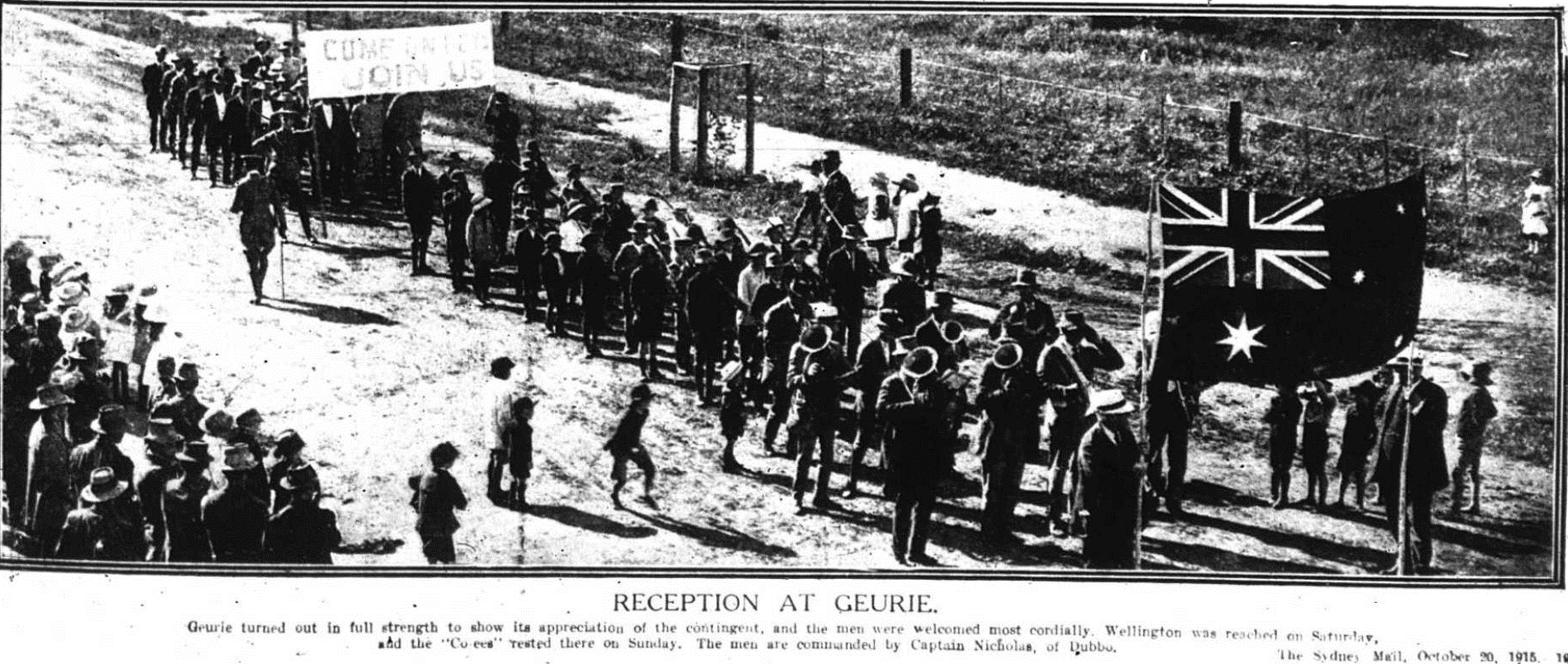

By the middle of 1915 the Call to War was running strong and the small town of Geurie did its part. On 21 September 1915, 23 year old Herbert enlisted at Dubbo. He was assigned to the 20th Battalion, 8th Reinforcements and was sent for his military training at the Liverpool Camp, west of Sydney.

A month later the “Cooee March”, which went over 400 km from Gilgandra to Sydney, came through Geurie and it helped to aid the enlistment of over 300 soldiers. Herbert James’ step-brother Herbert May (1698) enlisted on 13 December 1915 and was assigned to the 14th Machine Gun Company, the same Brigade as Herbert.

Herbert departed Sydney for Egypt on 27 December 1915 on HMAT A35 Berrima. As he arrived, major reorganizations in the troops were underway following the heavy losses at Gallipoli and the thousands of new recruits streaming in from Australia. In mid-February 1916, the 54th Battalion was formed at Tel-el-Kebir. On 21 March Herbert was assigned to the new battalion, in D Company. Training of the old and new hands continued.

By the end of March, much of the basic training in musketry and bayonet use had been completed for all of the new soldiers and they were sent to Ferry Post, on foot, a trip of about 60 km that took three days. It was a significant challenge, walking over the soft sand in the 38°C heat with each man carrying their own possessions and 120 rounds of ammunition. After arriving at the Ferry Post camp they were rewarded with being able to have a swim in the Canal.

The troops spent all of May at the front line trenches in Katoomba Heights, 8 miles from the Suez Canal. Herbert May arrived in Egypt in mid-May, so the boys were united before heading to France.

Fromelles

The call to the Western Front to join with the British Expeditionary Force came and on 20 June and the 982 soldiers of the 54th Battalion left Egypt. They sailed on the H.T. Caledonian for the 10 day trip to Marseilles via Malta. After disembarking in France there was a three day train trip to Hazebrouck, 30 km west of Fleurbaix.

By 2nd July the Battalion was billeted in barns, stables and private houses in Thiennes for a week of training. This now included use of gas masks and exposure to the effects of the artillery shelling. It was hoped that these tests would “inspire the men with great confidence”.

Source: AWM4 23/71/6 54th Bn War Diaries July 1916 page 2

On 10 July they moved to Sailly sur la Lys and on the 11th they were into the trenches in Fleurbaix. The health and spirit of the troops was reported as good.

After a few days getting exposed to the trenches, they moved back to billets in Bac-St-Maur.

Major Roy Harrison wrote home on July 15th. With his Gallipoli experience, the tone in this letter was certainly circumspect for the upcoming battle:

“The men don’t know yet what is before them, but some suspect that there is something in the wind. It is a most pitiful thing to see them all, going about, happy and ignorant of the fact, that a matter of hours will see many of them dead; but as the French say ‘C’est la guerre’.”

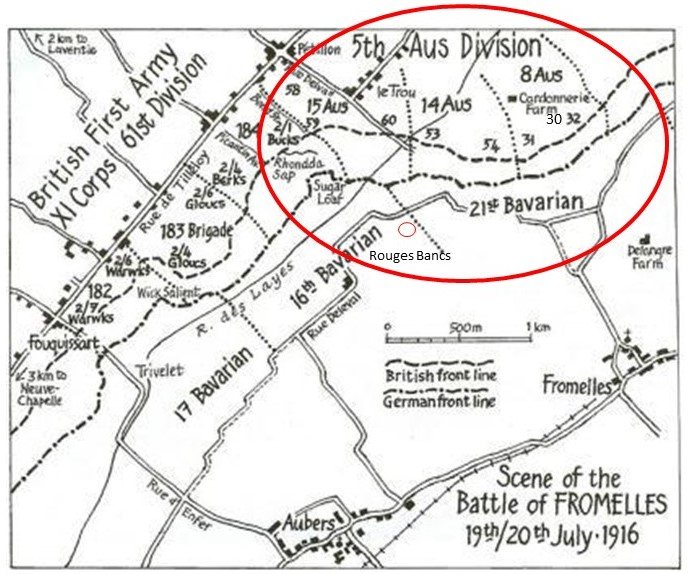

An attack was planned on the 17th, but it was delayed due to the weather. The weather soon improved and by 2.00 PM on 19th July they were in back in the trenches, ready for the Germans. The main objective for the 54th was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the 54th and the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfiled fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction.

As they advanced, they were to link up with the 31st and 53rd Battalions. The attack began at 5.50 PM. They moved forward in four waves– half of A & B Companies in each of the first two waves and half each of C & Herberts’ D Company in the third and fourth. Herbert May’s Machine Gun unit followed into battle after the infantry waves. The first waves of soldiers did not immediately charge the German lines, they went out into No-Man’s-Land and laid down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift. At 6.00 PM, the German lines were rushed.

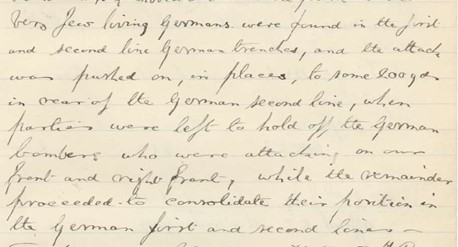

The 54th were under heavy artillery, machine gun and rifle fire, but were able to advance rapidly, taking the German’s first and second line trenches. The 14th Brigade War Diary notes that the artillery had been successful and “very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches”.

Some of the advanced trenches were just water filled ditches which needed to be fortified to be able to hold their advanced position against future attacks. There was heavy artillery, machine gun and rifle fire, but they were able to advance and link up with the 53rd on their right and, with the 31st and 32nd, occupy a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm. However, the 60th on their far right had been unable to advance due to the devastation from the machine gun emplacement at the Sugar Loaf, leaving this flank exposed. They held their lines through the night.

However, with heavy losses and the German counterattacks, the Australians were eventually forced to retreat. This was complicated by the fact that the exposed right flank of the 54th had allowed the Germans access to the first line trench BEHIND the 54th/53rd and the German advances in the trench had to repelled. By 7.30 AM on the 20th July, the 54th were pulled all the way back to Bac-St-Maur, 5 km from the front.

In this very short period of time, of the 982 soldiers of the 54th that left Egypt, initial roll call counts were: 73 killed, 288 wounded and 173 missing. Herbert James was among the missing.

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large amount of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield.

Ultimately, 173 soldiers from the 54th were killed in action or died from their wounds. Of this, 102 were missing, but 28 of these soldiers have since been identified through DNA testing and have been formally reburied in the Pheasant Wood Cemetery.

After the Battle

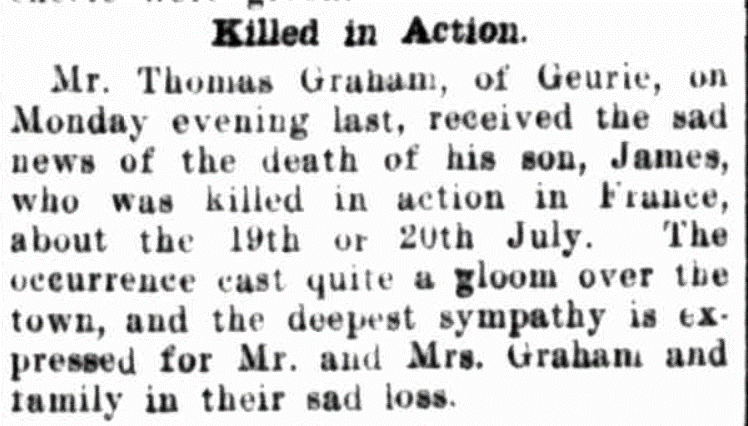

There are no known records of what happened to Herbert James during the battle, other than that he was missing. His family were notified of his death shortly after the battle. As was cited in the local paper, his death “cast quite a gloom over the town”.

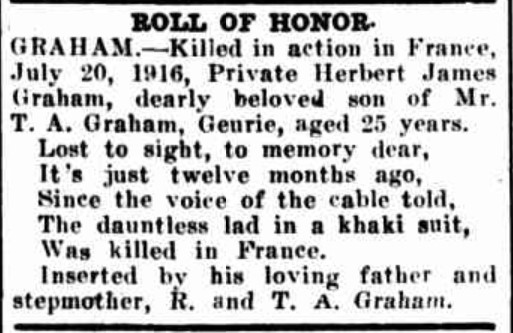

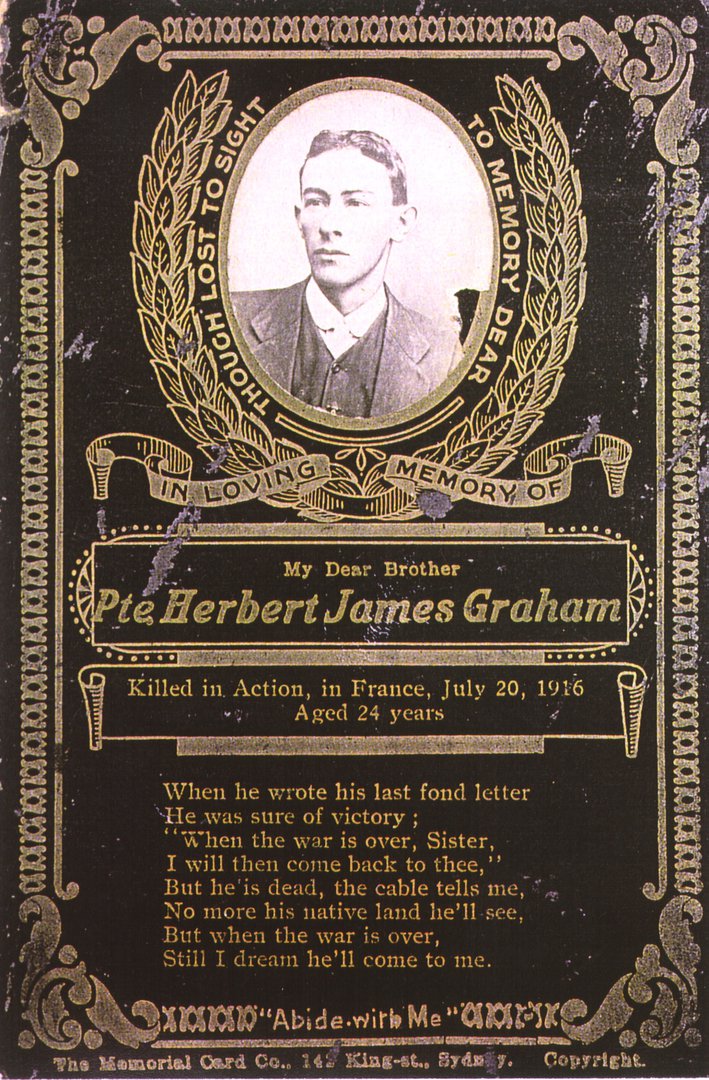

Herbert was clearly missed by his family. On the anniversary of his death, they placed a notice in the local paper:

Lost to sight, to memory dear,

It’s just twelve months ago,

Since the voice of the cable told,

The dauntless lad in a khaki suit,

Was killed in France.

Curiously, amongst all the chaos from these battles, there is a handwritten comment in his records that said Herbert WAS buried, at the St Riquier British Cemetery. However, this cemetery is 100 km from Fromelles. The soldier (also from the 54th Battalion) that is buried here is Harold Graham (1606) who died exactly two years later than Herbert James Graham (3543).

Herbert was awarded the Victory and British War Medals, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll.

He is commemorated at:

- VC Corner Australian Military Cemetery, Fromelles France

- Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour

- Coonambe War Memorial

- Wellington Cenotaph

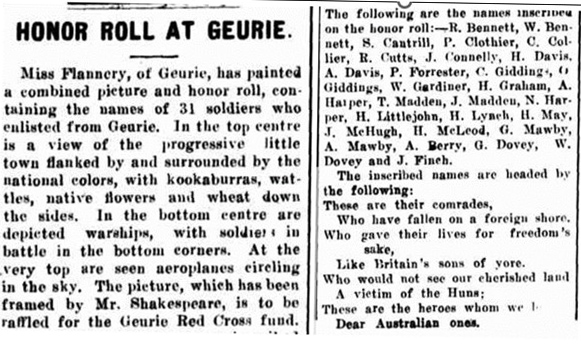

- Geurie Honour Roll

Herbert James was not the only war casualty from the family. Herbert May (1698) had fought with Herbert and did survive at Fromellles, but he was killed in action on 15 May 1917 during the Battle of Bullencourt. He also has no known grave. He is commemorated at Villers Bretonneux and at the Wellington NSW Cenotaph.

The small town of Geurie had 31 of its men who had signed up to serve by December 1917.

Another Geurie local, Clarence Timbrell Collier, 53rd Battalion, was killed in action at Fromelles and has no known grave.

“The Dauntless Lad in a Khaki Suit” is found in 2024

After the battle, German soldiers removed 250 Australian casualties from the battlefield, burying them in a large pit near Pheasant Wood. This mass grave was not discovered until 2008.

Identification by DNA matching has been ongoing since that discovery as relatives have been able to be located.

Herbert’s identification was announced on 23 April 2024. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers in the grave have been identified, including 28 of the 102 originally unidentified soldiers from the 54th. His headstone was unveiled at the Pheasant Wood Military Cemetery on 19 July 2024.

John Graham, Herbert’s grandnephew, and his son Josh were extremely pleased with Herbert’s identification.

John said, “The identification of Herbert has been received with great pride by my family”.

Josh said, “It gave me goosebumps when I got the call. My father John supplied his DNA because he was one stop closer, potentially, in the family tree, then Covid came through and everything got delayed; then I got a call last Thursday. It’s fantastic. Not having had a particular person to commemorate during Anzac Days past, this discovery has changed everything.”

While the news was kept secret until the identification was officially released, Josh began personal tributes immediately – laying an anonymous rose for Herbert with his kids Oscar and Charlotte during the Malabar RSL sub-branch Remembrance Day ceremony.

Further, Oscar was on a school excursion to Canberra which included a visit to the War Memorial. When the class was asked if they had any relatives associated with the Memorial, he was chuffed to point out Herbert’s name on the Wall of Remembrance.

Josh and his family attended the ceremony at Hyde Park in Sydney in July and they appeared in an article in a Sydney newspaper.

John went on to say, “I had intended going to Fromelles for the unveiling but unfortunately could not make it. It would have been the trip of a lifetime. I had been to Fromelles years ago not knowing about Herbert.

I asked Major David Wilson to do the honours for us at the ceremony (below). Herbert would have been pleased that one of his own looked after him.

The best we can do for Herbert is to ensure he is never forgotten. I have three children, ten grandchildren and three great grandsons. They have all adopted Herbert and I am sure over many years he will have more visitors than most.

We are most appreciative of the work done to be able to identify Herbert. It is obviously a labour of love, but it is more than that because of the pride it brings to the families of those identified.”

DEARLY BELOVED

SON AND BROTHER

THE DAUNTLESS LAD

IN A KHAKI SUIT

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).