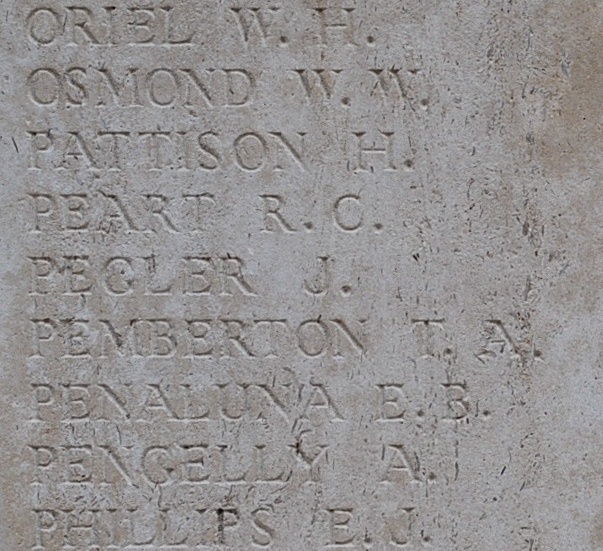

Henry PATTISON

Eyes blue, Hair brown, Complexion sallow

Harry Pattison – A Sailor Turned Soldier

Can you help find Harry?

Harry Pattison’s birth name is Harold, but he enlisted as Henry and was also known as Harry.

Harry’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial. Harry also had a younger brother Henry Edward, who seved in the British Army. Henry died three weeks after Harry.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

Harry may be among these remaining 70 unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in Manchester, England and in several states in the USA.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for Harry, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Early Life - From Lancashire to Melbourne via China and the Royal Navy

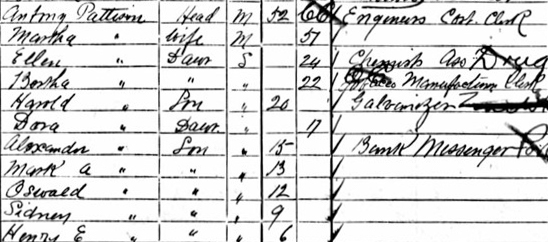

Harold “Harry” Pattison was born on 31 July 1880 at Salford, Lancashire, England, the son of Anthony Greyson Pattison and Martha Briggs. He was one of fourteen children:

- Edith (1871–1957)

- Mildred (1872–1953)

- Mary Beatrice (1874–1924)

- Herbert Grayson (1875–1906)

- Ellen (1876–1965)

- Agnes (1878–1954)

- Bertha (1879–1967)

- Harold “Harry” (1880–1916)

- Dora Martha (1883– )

- Alexander (1885– )

- Mark Anthony (1887–1973)

- Oswald (1889–1937)

- Sidney (1891–1951)

- Henry Edward (1894–1916) – King’s Liverpool Regiment, KIA

Brothers Harold and Henry shared similar names and used the nickname of Harry at times. Both enlisted as Henry - Harold in the AIF and Henry in the British Army. The brothers were killed on the Western Front within three weeks of each other. In this document, we are using Harry for Harold. In the 1901 UK census, Harold/Harry was 20 years old and working as a galvanizer. Henry was just six.

Harry’s siblings were employed in a range of jobs and locations. Alexander, Mark and Sidney migrated to the USA and Mary was a nurse in Moscow, Russia. Shortly after the 1901 census, Harry was in the Merchant Marines as a ‘mess room boy’ on the Lisbonense. In 1902 he joined the Royal Navy and was stationed in China after the Boxer Rebellion, as part of the Eight-Nation Alliance. This group provided relief for the foreign legations in Beijing besieged by the Boxer militiamen. After four years in the Royal Navy, Harry was released due to a conduct issue and returned to England.

He rejoined the Merchant Marines, where there was plenty of work given that Liverpool was one of the world’s leading ports at the time. By 1911, Harry was a 31 year old marine fireman on the ship Ashridge which arrived in Sydney on 18 July 1911 and then in Newcastle on 17 October 1911. This is probably when he chose to stay in Australia and crew on coastal ships. He finally chose to settle in Victoria. In 1912, he married Lucy May “Queenie” Peart in Victoria. Queenie had a young son, Francis Clyde Gillin Peart (1905–1983), who took Harry’s surname and became known as Francis “Frank” Peart Pattison. The family lived at 81 Stafford Street, Abbotsford, Victoria.

Off to War

When war broke out, Harry was still working from Melbourne as a fireman/marine stoker — a tough, physically demanding job that suited his seafaring background. Despite being 35 years old and previously rejected for enlistment on account of his teeth, he persisted and was finally accepted into the AIF on 15 September 1915 in Melbourne, Victoria. He was assigned to the 23rd Battalion, 8th Reinforcement. After his initial infantry training, he embarked from Melbourne aboard the HMAT A19 Afric on 5 January 1916 to join the troops being assembled in Egypt for deployment to the Western Front.

The voyage did not go smoothly. Harry deserted/missed his ship at Colombo, Ceylon, on 24 January 1916. However, he rejoined his unit in Egypt at Zeitoun by mid-March. Shortly after his arrival, he was transferred to the newly formed 60th Battalion, who were at Ferry Post guarding the Suez Canal and continuing their training. In the months that followed, Harry continued to find himself in trouble, not dissimilar to his time with the Royal Navy.

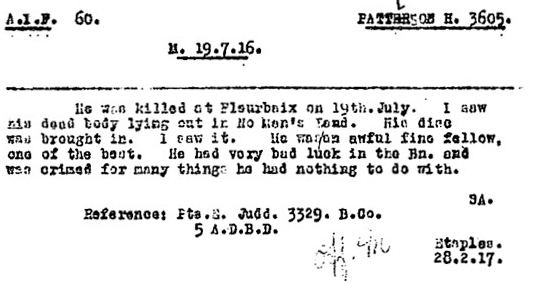

He was charged with neglecting orders and insubordination which earned him several periods of Field Punishment No. 2 (where a soldier was placed in fetters and handcuffs but was not attached to a fixed object, allowing the soldier to march with their unit). Harry’s most serious incident was a Field General Court Martial at Moascar on 12 June 1916, where he was sentenced to 59 days’ Field Punishment for repeated insubordination and being absent at roll calls and parades. Despite these issues, Private Edward Judd (3329), a fellow soldier from B Company, recalled a ‘much different’ Harry:

He was an awful fine fellow, one of the best. He had very bad luck in the Battalion and was crimed for many things he had nothing to do with.

Punishments aside, Harry sailed with his battalion for France aboard the transport ship Kinfauns Castle on 19 June 1916, disembarking at Marseilles ten days later. Within a month, he would be in the thick of his first and final battle — Fromelles.

The Battle of Fromelles

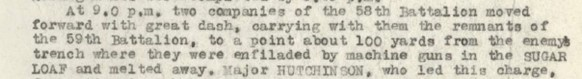

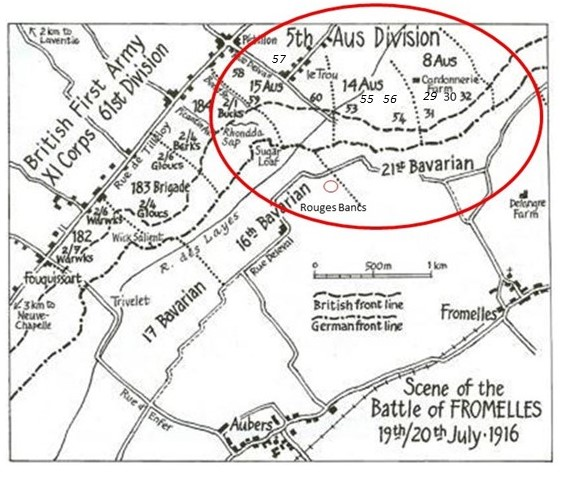

The battle plan had the 15th Brigade located just to the left of the British Army. The 59th and 60th Battalions were to be the lead units for this area of the attack, with the 58th and 57th as the ‘third and fourth’ battalions, in reserve. The main objective for the 15th Brigade was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfilade fire from the machine-guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 59th and 53rd Battalions on their flanks.

The 60th Battalion faced an especially difficult position in the assault, right across from the ‘Sugar Loaf’. On 17 July, they were in position for the major attack, but it was postponed due to unfavourable weather. There was a gas alarm, but luckily it was just that. Two days later, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties.

A fellow soldier, Private Bill Boyce (3022, 58th), summed the situation up well,

“What have I let myself in for?”

Source: Australian War Memorial Collection C386815

The Aussies went over the parapet at 5.45 PM in four waves at 5 minute intervals, but then lay down to wait for the support bombardment to end at 6.00 PM. A & B Companies were in the first two waves, C & D in the next two. Casualties were immediate and heavy. The 15th Brigade War Diaries captures the intensity of the early part of the attack – “they were enfiladed by machine guns in the Sugar Loaf and melted away.”

The British 184th Brigade just to the right of the 59th met with the same resistance, but at 8.00 PM they got orders that no further attacks would take place that night. However, the salient between the troops limited communications, leaving the Australians to continue without British support from their now exposed right flank. It was reported that some got to within 90 yards of the enemy trenches. One soldier said he “believed some few of the battalion entered enemy trenches and that during the night a few stragglers, wounded and unwounded, returned to our trenches.”

Source - AWM4 23/77/6, 60th Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 3.

Fighting continued through the night. With known high casualties in the 60th, they were relieved by the 57th Battalion at 7.00 AM. Roll call was held at 9.30 AM. In the ‘Official History of the War’, C.W. Bean said “of the 60th Battalion, which had gone into the fight with 887 men, only one officer and 106 answered the call.”

Source - Chapter XIII page 442

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The final impact of the battle on the 60th was that 395 soldiers were killed or died of wounds, of which 315 were not able to be identified.

Harry’s Fate

Given the dire situation that the 60th faced in the battle, Harry’s fate does not come as a surprise. Harry’s mate, Private Edward Judd of B Company told the Red Cross:

“He was killed at Fleurbaix on 19th July. I saw his dead body lying out in No Man’s Land. His disc was brought in. I saw it.”

Harry was initially reported as Missing in Action, but following an Enquiry in the Field held on 15 September 1916, he was officially declared as having been Killed in Action on 19 July 1916. He was 36 years old.

After the Battle

While Harry’s fate was formally declared soon after the battle, Queenie received no hard news as to what happened to Harry. Even two years later she wrote to Base Records and the Red Cross from her home at 78 Kent Street, Richmond, Victoria:

“I am sorry to inform you I have no letters or papers bearing on my husband’s death... He was reported missing on the 19 July later killed on that date... A number was found and brought in, and a stretcher bearer named Judd saw his body. Perhaps they may be able to give more news.”

Despite her request, Base Records Office’s form letter advised Queenie - “After full investigation, this office regrets to advise that no information has been obtained regarding the burial of your husband, the late No. 3605 Private H. Pattison, 60th Battalion. It is therefore concluded that he has no known grave.” Source - NAA B2455, PATTISON Henry – First AIF Personnel Dossiers 1914–1920, p. 16

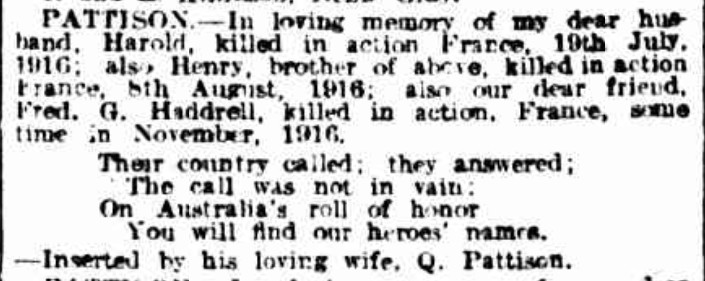

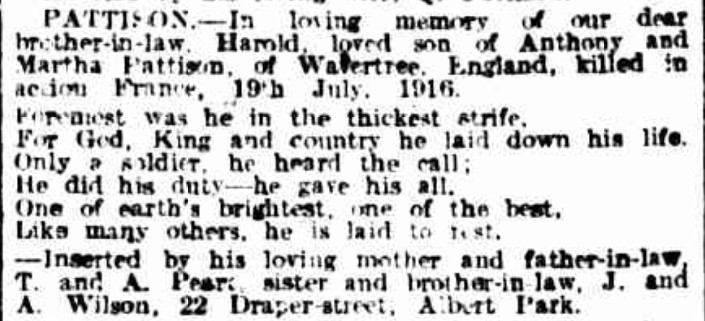

Harry’s family suffered a further loss during the Great War. His younger brother, Private Henry Edward served with the King’s Liverpool Regiment and was killed in action on 9 August 1916 at the Battle of Guillemont, less than three weeks after Harry fell at Fromelles. In the years following the war, Queenie and her family placed several memorial notices in The Age to honour Harry’s sacrifice and to remember his brother Henry and their friend Fred Haddrell. These tributes offer a glimpse into the grief felt by those left behind.

14 September 1916 -

Killed in action, France, previously reported missing, 19th July, Harry, dearly loved husband of Lucy (Queenie) Pattison, 81 Stafford Street, Abbotsford.For King and country.

Source: Family Notices. (14 September 1916). The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854–1954), p. 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article155166087

And, despite having been married just a few years before he left for the Western Front, Queenie’s family memoriam notice suggests Harry was well embraced by his Australian family.

For his service, Harry was awarded the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll. Harry’s death meant Queenie was widowed at 35. She later lived in Mordialloc, Victoria and died on 28 May 1940, at 59. She is buried at Kew Cemetery, Victoria. Though Harry’s grave is unknown, his story endures — a sailor turned soldier whose enlistments carried him across the world, in war and peace - from Manchester to Abbotsford and finally to the fields of Fromelles.

Finding Harry

Harry’s remains were not recovered; he has no known grave. After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including two of the 315 unidentified soldiers from the 60th Battalion. We welcome all branches of Harry’s family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification.

If you know anything of family contacts, please contact the Fromelles Association, especially from extended family — especially from both Pattison and Briggs lines from Lancashire and Harry’s family in the USA. We hope that one day Harry will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Roy’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Harold “Harry” Pattison (1880–1916) - Henry in AIF file) |

| Parents | Anthony Greyson Pattison (1848–1932) and Martha Briggs (1849–1927) |

| Siblings | Edith (1871–1957) m James Burgess | ||

| Mildred (1872–1953) m Joseph Anders | |||

| Mary Beatrice (1874–1924) nurse, died Moscow | |||

| Herbert Grayson (1875–1906) | |||

| Ellen (1876–1965) Did not marry | |||

| Agnes (1878–1954) m Joseph Hunt | |||

| Bertha (1879–1967) m Gilbert Hutchison | |||

| Dora Martha (1883– )m William Timm | |||

| Alexander (1885– ) to Detroit, USA 1909 | |||

| Mark Anthony (1887–1973) d. Florida USA | |||

| Oswald (1889–1937) m Ada Gilbert | |||

| Sidney (1891–1951)d. New York, USA | |||

| Henry Edward Pattison (1894–1916) – KIA, King’s Liverpool Regiment, 9 August 1916 |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Father unknown and Elizabeth Pattison (c.1826–1856) | ||

| Maternal | Isaac Briggs (1811–1890) and Susannah Ramsbottom (1814–1856) |

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).