William FLETCHER

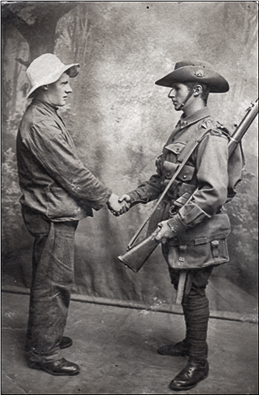

Eyes blue, Hair light brown, Complexion fresh

A Tale of Will and Archie Fletcher, two brothers who served in the Great War

We thank Fred Boland whose grandmother, Isabella, was sister to William and Archibald, for his efforts in telling this story of the two Fletcher brothers.

This is unfortunately an all-too-common tale of a family involved in the Great War. Many others would have similar tragic accounts of their lost loved ones. The fact that two brothers enlisted was also not uncommon, as there were families with up to eight sons who enlisted. As we look back now on the experiences of these two brothers and others who served their country, it does seem exceptional in the light of our lives today.

William Fletcher, born in 1880 in Dunedin, New Zealand, was the second of eight children of James Jack Fletcher and Jean (nee Malcolm). His parents had emigrated from Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland in 1876 and married in New Zealand in 1877.

Their five eldest children (James, William, Robert, Agnes, Isabella) were born in New Zealand though Agnes died as an infant. The family moved to Victoria in 1887 where the three youngest (Margaret, John, Archibald) were born, with Archibald, the youngest, born in 1892. They settled in the suburb of Fitzroy in Melbourne where James worked as a labourer and the children attended the local state school.

Aged about 24, Will married Eliza Walsh and had two daughters – Elsie Lillian in 1904 and Alma in 1905. Sadly, Alma died at four months and the marriage did not last with Will and Eliza separating in 1908. By 1912, Will and little Elsie were living with his parents and brother, John, at 34 York Street, North Fitzroy where they lived for some years. Will was employed as an iron moulder while his father and brother were listed in the electoral roll respectively as a labourer and a bricklayer.

In 1913, 21-year-old Archie married Harriett Siddall and in early 1915 they were living in a terrace house at 55 Station Street, Carlton.

1915: Archie and Will enlist in the AIF

Archie was the first to enlist on 8th January 1915 aged 22 and his occupation was noted as ‘driver’, most likely of the newly installed tram car in Fitzroy. The eldest of the Fletcher brothers, James, was employed as a conductor also on ‘the car’.

Archie, service number 1751, was assigned to the 4th Reinforcement 7th Battalion, 2nd Infantry Brigade as a private and embarked from Melbourne on the HMAT A18 Wiltshire on 13th April 1915. He joined his battalion on 22nd May and arrived at Gallipoli Peninsular some four days later. Three days after his arrival he sustained a shrapnel wound to the head.

Archie was admitted to the hospital ship Newmarket and then sent to Malta for two months at the St George’s Hospital where he contracted rheumatic fever requiring further medical treatment.

Meanwhile, on 26th January 1915, Will enlisted at the age of 34, two weeks after his youngest brother had signed up. Will was allotted to the 21st Battalion B Coy and they embarked on HMAT A38 Ulysses from Melbourne on 8th May 1915 to Egypt. It was not until the end of August that the 21st travelled via Lemnos to finally join the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force at Gallipoli. The Australian War Memorial website (AWM) describes it as follows:

“The 21st Battalion arrived in Egypt in June 1915. As part of the newly raised 2nd Australian Division, it proceeded to Gallipoli in late August. It was an eventful trip; the battalion's transport was torpedoed near the island of Lemnos and had to be abandoned. The battalion finally landed at ANZAC Cove on 7 September. It had a relatively quiet time at Gallipoli, as the last major Allied offensives had been defeated in August.”

At much the same time that Will arrived at Gallipoli, Archie was finally discharged from hospital and embarked on the Megantic for the Dardanelles to re-join his battalion in early September 1915. Archie and Will served at Gallipoli with their respective units until the mid-December evacuation of Australian forces described by AWM:

Over 5 nights, 36,000 troops were withdrawn to the waiting transport ships. The last party left in the early hours of 20 December from North Beach at Anzac. British and French forces remained at Helles until 9 January 1916.

Egypt

With Australian troops based in Egypt for the first half of 1916, Will spent a fair portion of his months in the Suez Canal zone on the sick list, suffering variously from diarrhoea, laryngitis, influenza and finally defective vision. In the periods that he was released from hospital, he would have continued training exercises with his unit. In April, as part of the general troop re-organisation after Gallipoli, he was released from the 7th Battalion and taken on strength by the 57th Battalion and then transferred to the 60th Battalion.

On 18th June 1916, Will embarked from Alexandria on the troopship “Kinfaun’s Castle” to join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), disembarking at Marseilles en-route to Armentieres arriving in early July 1916.

In contrast, Archie spent less than three months in Egypt as the 7th Battalion left Egypt for France at the end of March. After arrival in Marseilles, they had a long slow three-day train trip to Bailleul before heading into a long period in the trenches on the Somme – including about six weeks at Fleurbaix (near Fromelles) until early June about a month before Will arrived there with his unit. By the time of the Battle of Fromelles, Archie was already at Varennes on the Somme, preparing for the Battle of Pozieres the following week.

The Battle of Fromelles

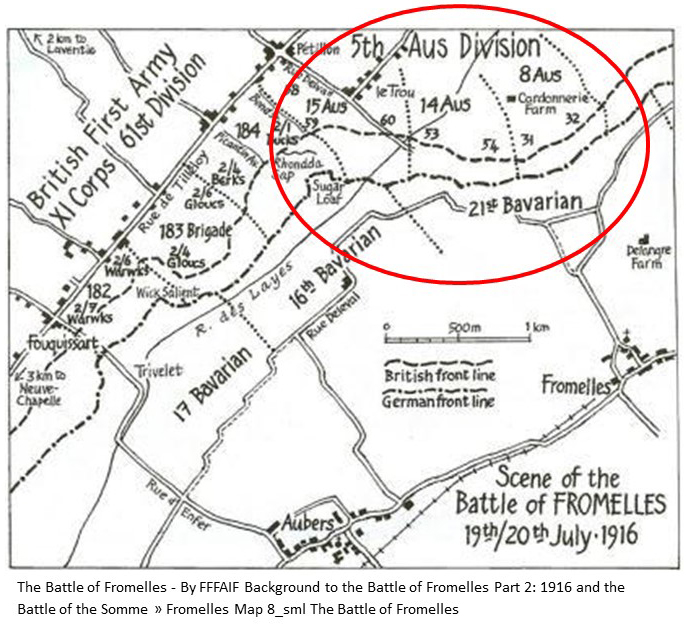

The Battle of the Somme had begun in early July and was to last until November 1916. As a diversionary tactic it was decided to attack the entrenched German positions at Fromelles with the hope of preventing German troop movement to the Somme.

It was to here that Will was sent after his arrival at Armentieres in early July 1916.

This was the second time the British High Command committed troops to Fromelles after the first British attempt was met with devastating resistance and slaughter. The second Battle of Fromelles started on 19th July 1916 at about 06:00pm in broad daylight not withstanding vigorous protests by General ‘Pompey’ Elliot to his superiors that his troops were facing almost certain death.

So it was that, near the small French village of Fromelles in the late afternoon of 19th July 1916, Will Fletcher was involved in an infantry charge over open ground towards concrete bunkers housing well entrenched German machine guns of the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division.

There was heavy artillery from both sides. The first wave of Aussies went over the parapet at 6:45pm with the last wave going over at 7:00pm. They were in a very difficult position with the ongoing bombardment, facing short range fire from the German trenches as well as crossfire from the machine gun emplacement on the Sugar Loaf salient, just a short distance away. One soldier reported that their unit only got to within 90 yards of enemy trenches, but another said he “believed some few of the battalion entered enemy trenches and that during the night a few stragglers, wounded and unwounded, returned to our trenches.”

Fighting continued through the night. With the known heavy casualties in the 60th, they were relieved by the 47th Battalion at 7:00am.

Roll call was held at 9:30am. Official historian Charles Bean said:

“of the 60th Battalion, which had gone into the fight with 887 officers and men, only one officer and 106 answered the call.”

Will Fletcher did not make it and was listed on 20th July as ‘Missing in Action’.

Waiting for news at home

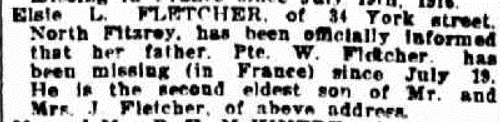

The Fletcher family were officially notified in early September 1916 (about 6 weeks after the battle) that Will was missing but they had no further news for some time.

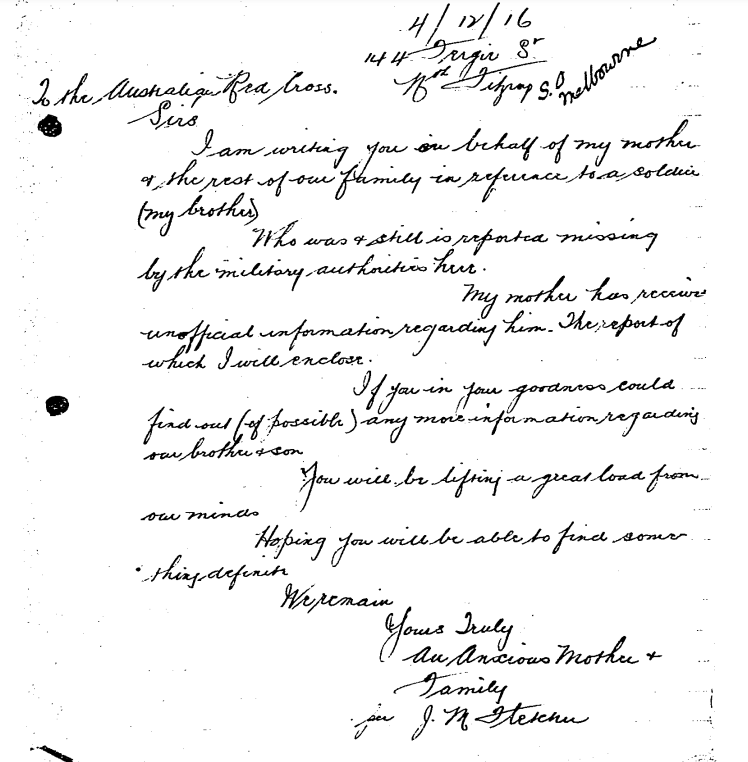

It seems that the family eventually received information from unofficial sources as to Will’s fate. It was common for soldiers who survived to write home to the families of mates who were killed as they knew that families were desperate for news of loved ones. Accordingly, on 4 December 1916, Will’s eldest brother, James, wrote to the Red Cross begging for information – something definite – to help lift a great load from a very anxious family.

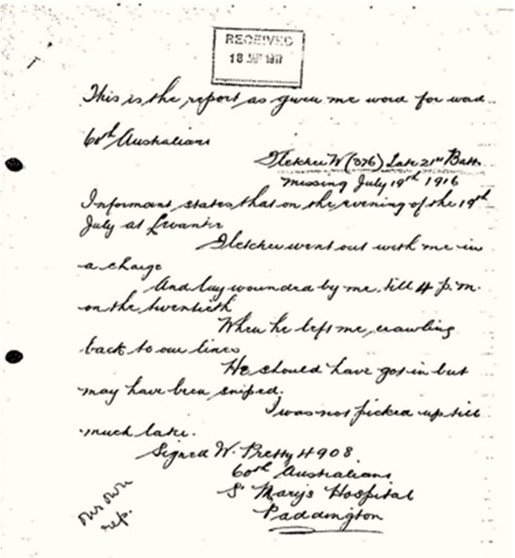

There is no record on file of the reply but, if the Red Cross followed their common practice, it is likely that they replied giving the details supplied to their representatives by Pte 4908 Harold W. PRETTY. Harold was recuperating from his wounds in England when he gave evidence from his hospital bed on 11 October 1916 stating that on:

“the evening of July 19th at Laventie, Fletcher went out with me in a charge, and lay wounded by me till 4 p.m. on the 20th, when he left me, crawling back to our lines[.] He should have got in, but he may have been sniped. I was not picked up till much later".

It is possible that the information received by Will’s mother may even have been from a letter sent personally by Pte Pretty.

Note the reference by Pte Pretty to Laventie rather than Fromelles or Fleurbaix. The Museum of the Battle of Fromelles explains that:

‘Laventie was the closest village for British and a part of Australian soldiers (including the 60th Battalion). Many weren’t able to spell or write Fleurbaix (many wrote Florbaix, Flore bay, Fleurbay, etc.) and the centre of the village looked close from the trenches. Most of the soldiers passed through Laventie, and sometimes talked about this village for the battle.’

Eventually, a Court of Enquiry in the Field was held in France on 4th August 1917 and Pte Will Fletcher was officially declared ‘Killed in Action’ on 19th July 2016. Next of kin was advised of the outcome on 25 August 1917 and, more than a year after the battle, Will’s family finally had a definite answer.

After the war, Elsie received her father’s service medals (1915 Star, Victory Medal and British War Medal) and memorial plaque and scroll. She continued living with her grandparents for many years, possibly until their deaths in the early 1930s. Elsie worked as a bookkeeper and married John Cormack in 1935, living to the age of 93 years.

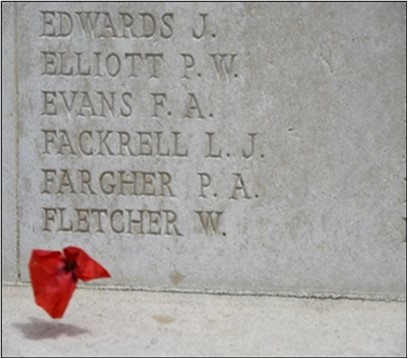

Will has no known grave but is commemorated with his fellow soldiers at V.C. Corner at the Australian War Memorial and Cemetery at Fromelles.

William Fletcher, a true Anzac - born in New Zealand, grew up in Australia, lost on a French battlefield.

And what of Archie?

At the time of his brother’s death, Archie was also in the trenches and his battalion was heavily involved in action at the Somme and later at Ypres but from October 2016 Archie’s health and behaviour deteriorated. He was in and out of field hospitals at St Omer, Etaples and Rouen, suffering variously from severe neuritis, ruptured tympanum, herpes zoster and Vincent’s Angina (trench mouth). He was eventually evacuated and admitted to University War Hospital in Southampton England in August 1917.

There was a further blow when his brother-in-law, Jack Cooper - Lance Corporal 4753 John Thomas Cooper, a popular Victorian Football League player and captain of Fitzroy Football Club before the war - was killed on 20th September 1917 on the Menin Road Ridge during the battle of Passchendaele and is memorialized at the Menin Gate Memorial. Not only was Jack a member of the family (married to Margaret, Will and Archie’s youngest sister), but he was also a close neighbour with Jack and his wife living a few doors away in York Street.

After spending time at various military hospitals, in early December 1917 Archie re-joined his unit in time for the ‘German Spring Offensive” in early 1918.

Archie returned home to Australia on the City of Poona, arriving in Melbourne in May 1919, but not without a brush with the law and the Old Bailey in London first! It appears that he never recovered, physically or psychologically, from his head wound, the loss of his brother Will, his brother-in-law Jack, and the tragic events of the war.

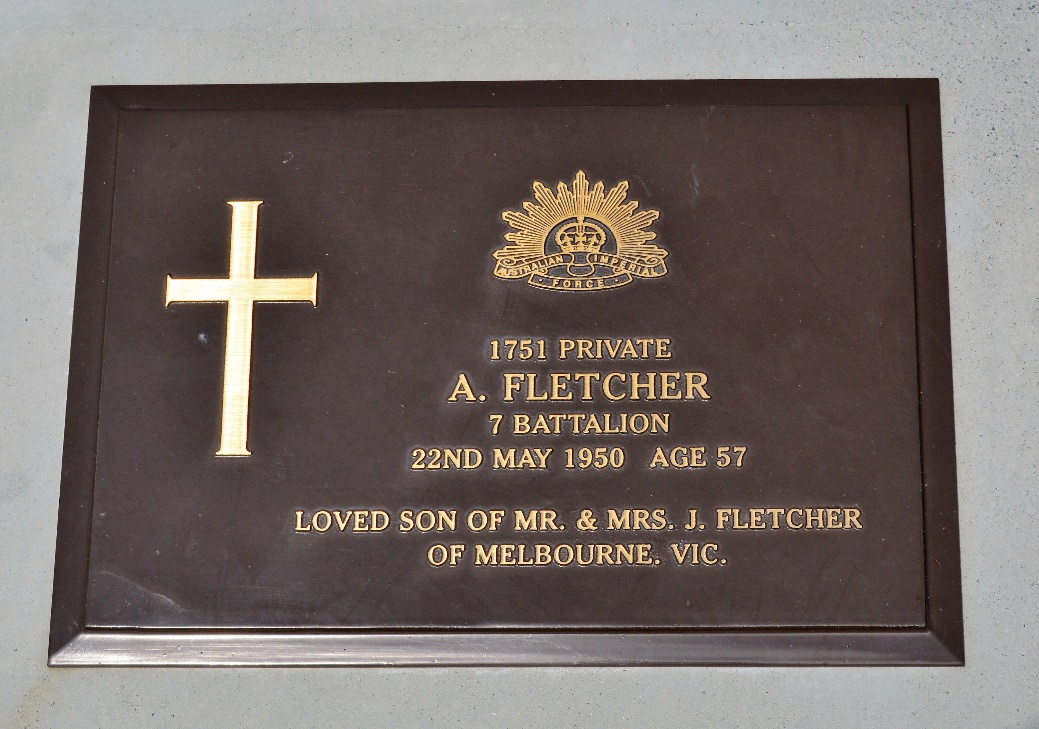

His mental state deteriorated rapidly to such an extent that he spent several years at the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum on Stradbroke Island in Queensland before discharging himself in 1946. He died at the age of 57 in 1950 and is buried at Lutwyche Cemetery, Brisbane.

“You hear about men who were wounded and sent back to the frontline five or six times and when they got home, they were locked in a mental institution because they were shell-shocked," said Matt Rennie OAM, Korean War veteran.”

[[Source: Baz Ruddick, ABC News, 25 April 2020_12183570 – Veteran strives to name 72 unmarked graves of servicemen who died ‘shell shocked’ in mental asylum.]]

LEST WE FORGET

Helping to identify Will Fletcher

We are unaware of the status of DNA donations as at 23 April 2023, but this detail will be added to the story as soon as is possible. If you have information that may assist, please contact us.

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).