Isaac LINWOOD

Eyes brown, Hair brown, Complexion dark

Isaac Linwood - The Bullet That Saved Him

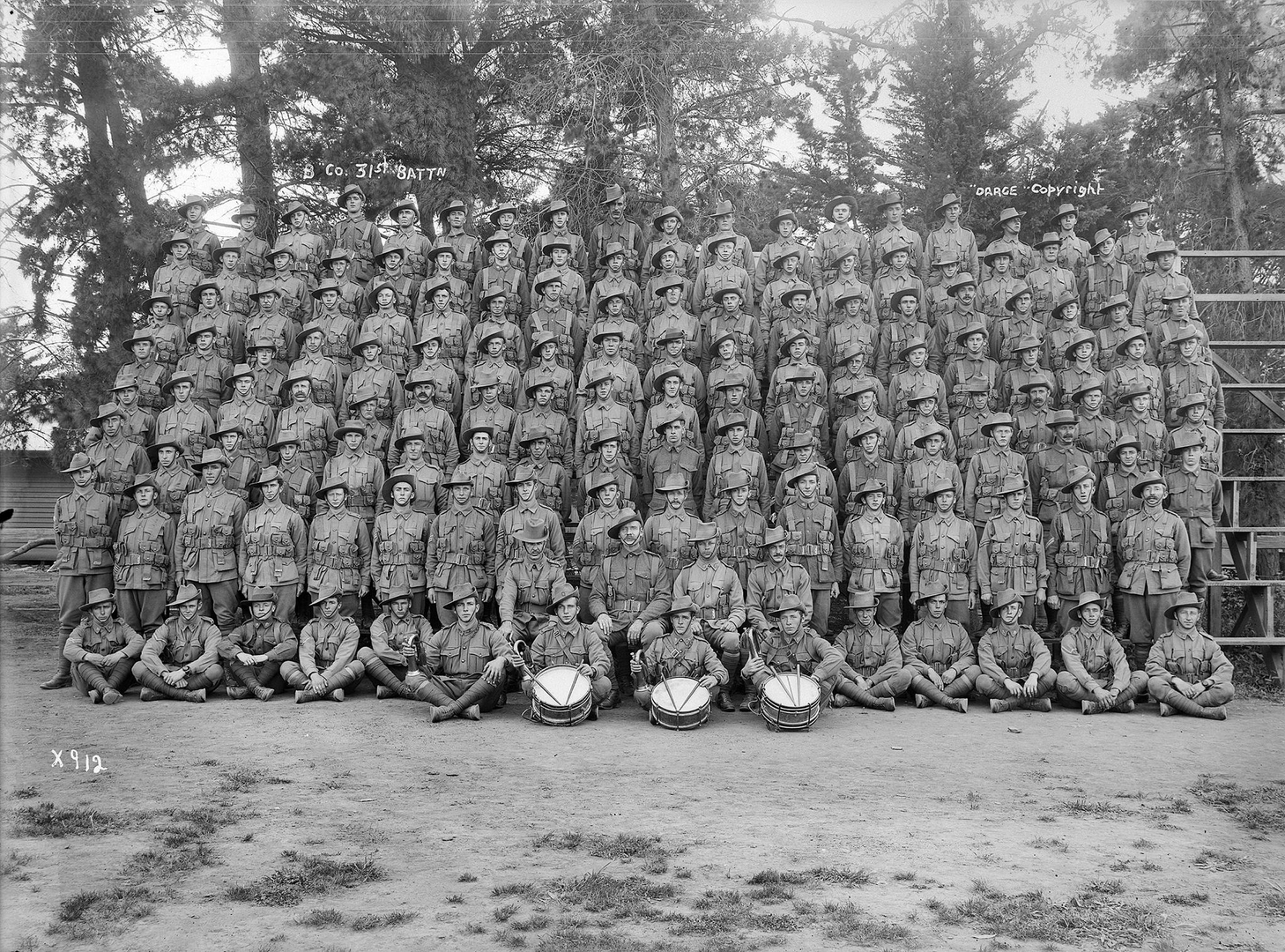

With thanks to Lieutenant Colonel Russell Linwood, ASM, 31st Battalion for his help in writing this story

Early Life

Isaac Linwood was born on 23 June 1893 in Bundaberg, Queensland — the eleventh of at least seventeen children born to John Linwood and Hannah (Anna) Chapman. His father, John, a labourer from Stetchworth, Cambridgeshire, had migrated to Queensland in 1874 aboard the St James, shortly after marrying Hannah in England. The couple settled in Bundaberg during its boom years as a sugar-growing district, part of the expanding frontier of colonial Queensland. The Linwoods lived in South Bundaberg — a working-class neighbourhood close to mills, rail lines and river wharves.

Their large family was typical of the time, though marked by early loss: three of Isaac’s siblings died in infancy. When his father died in 1909 at the age of 55, Isaac was only 16. The burden of supporting the younger children fell heavily on the older siblings and on their mother, Hannah, who remained the family matriarch until her death in 1925. The Linwoods were members of the Church of England and deeply embedded in the life of Bundaberg. Isaac’s formal education was likely brief. By his early twenties, he was working as a labourer and was listed in 1915 as living at South Bundaberg, care of Miss Alma Alley, who would later become his wife. Like so many Queensland families of the time, the Linwoods would come to experience the First World War not just as distant news, but as a deeply personal loss.

Off to War

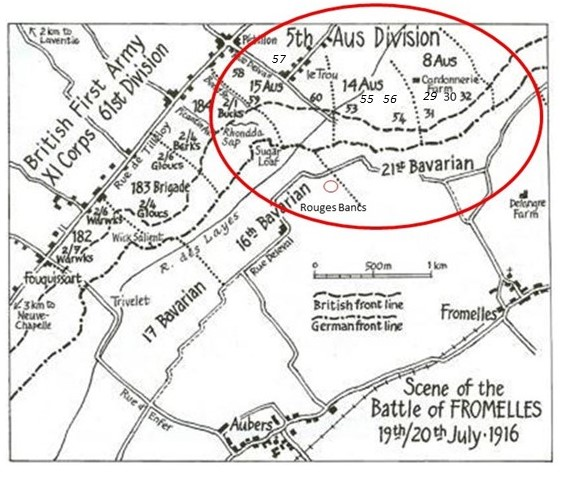

Isaac enlisted on 8 July 1915 in Bundaberg, Queensland, just weeks after his 22nd birthday. Like many young men from the regional towns, he was assigned to one of the newly formed Queensland–Victoria composite units - the 31st Battalion, which was part of the 8th Brigade, 5th Division.

He was in B Company. In October 1915, the battalion moved into camp at Broadmeadows, Victoria, where they trained alongside Victorian recruits. There, they became a thousand others preparing for the front — men who had never seen battle but were now rapidly being turned into soldiers. Before sailing from Melbourne on 9 November aboard the troopship Wandilla, the 991 soldiers of the 31st had been on parade in Melbourne in front of a good crowd. The Minister for Defence, H.F. Pearce said:

“I do not think I have ever seen a finer body of men.”

The Wandilla docked at Port Suez exactly four weeks after leaving Melbourne. They were first sent to Serapeum to continue their training and to guard the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army. Near the end of February they moved to the large camp at Tel-el-Kebir , which was about 110 km northeast of Cairo. The 40,000 men in the camp were comprised of Gallipoli veterans and the thousands of reinforcements arriving regularly from Australia. The 60 km trip must have been unpleasant, as it was reported that they were moved in “dirty horse trucks.”

Source - AWM4 23/48/7, 31st Battalion War Diaries, Feb 1916, page 5

The next move was at the end of March, back to the Suez Canal at the Ferry Post and Duntroon Camps and then finally to Moascar at the end of May. The months passed in training and sightseeing, but by the time the 31st Battalion was transferred to France, the men were all heartily sick of Egypt. Private Les Smith’s (934) letter home pretty well sums it up - “We are eating dust and sand pretty near all day. It is couple of few feet deep and not a tree to be seen for miles. We are drilling in this and the heat of the sun which is about 100 in the shade.”

Source- SOLDIER'S LETTER. (1916, April 28). Maryborough and Dunolly Advertiser (Vic. : 1857 - 1867 ; 1914 - 1918), p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article90591462

On 15 June, the 31st Battalion began to make their way to the Western Front, first by train from Moascar to Alexandria and then sailing to Marseilles. A, B and D companies were aboard the troopship Hororata and C company aboard the Manitou. After disembarking on 23 June, they were immediately boarded onto trains (cattle wagons marked “40 Hommes – 8 Chevaux,”) to Steenbeque and then marched to their camp at Morbecque, 35 km from Fleurbaix in northern France, arriving on 26 June. The battalion strength was 1019 soldiers.

The area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. Training continued, now with how to handle poisonous gas included in their regimen. They began their move towards Fromelles on 8 July and by 11 July they were into the trenches for the first time, in relief of the 15th Battalion.

The Battle of Fromelles

The overall plan was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The main attack was planned for the 17th, but bad weather caused it to be postponed. On the 19th they were back into the trenches and in position at 4.00 PM. The Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared:

“Just prior to launching the attack, the enemy bombardment was hellish, and it seemed as if they knew accurately the time set.”

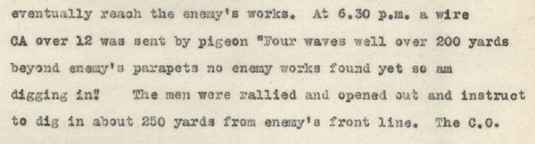

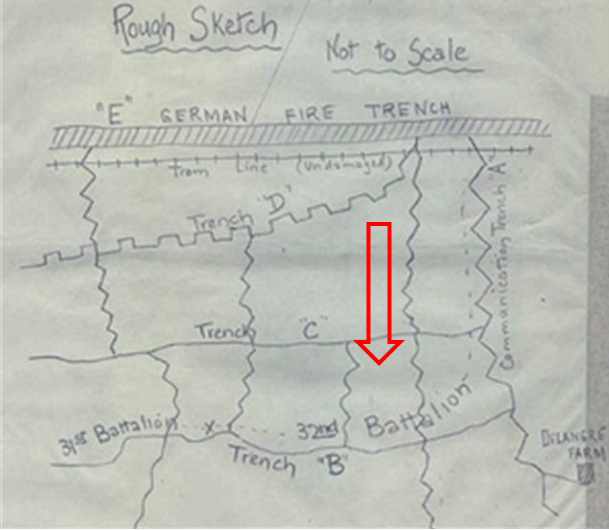

The assault began at 5.58 PM and they went forward in four waves, A and C Company in the first two waves and B and D Company in the 3rd and 4th waves. There were machine gun emplacements to their left and directly ahead at Delrangre Farm and there was heavy artillery fire in No-Man’s-Land. The pre battle bombardment did have a big impact and by 6.30 PM the Aussies were in control of the German’s 1st line system (Trench B in the diagram below), which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom.”

Source - AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

Unfortunately, with the success of their attack, ‘friendly’ artillery fire caused a large number of casualties. By 8.30 PM the Australians’ left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and the 32nd, who also had the job of holding the flank to the left of the 31st, were told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source - AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine-gun fire from behind from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map). Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, portions of the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers.

At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left themselves, the only resistance the 31st could offer was with rifles.

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled a shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

Source: AWM4 23/48/12, 31st Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 29

The 31st were out of the trenches by the end of the day on the 20th. From the 1019 soldiers who left Egypt, the initial impact was assessed as 77 soldiers were killed or died from wounds, 414 were wounded and 85 were missing. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The ultimate total was that 162 soldiers of the 31st were either killed or died from wounds and of this total 82 were missing/unidentified.

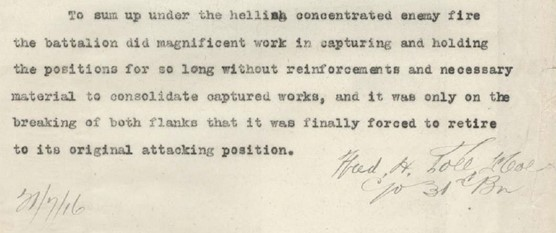

To date (2025), 23 of those missing have been identified from the mass grave the Germans dug at Pheasant Wood that was discovered in 2008. They are now properly buried in the Pheasant Wood Cemetery. The bravery of the soldiers of the 31st was well recognised by their own Battalion commanders.

Isaac’s Battle

Isaac was among those assembled in the trenches ready for the attack, but before he could go over the top, he was hit by enemy fire. His wounds saw him evacuated from the front and after initial treatment in France he was sent to England to recover. Like so many, his name did not appear on official casualty lists until weeks later — leaving his mother Hannah and the rest of the family in Bundaberg in anxious limbo as the devastating results were broadcast back home. Eventually, word came through that Isaac had been wounded, not killed or captured.

Following months of recuperation in England, Isaac was sent back to France in August 1917. But his return to the front was short-lived. He soon developed trench feet — a debilitating condition caused by prolonged exposure to cold, wet, and unsanitary conditions in the trenches. The damage was enough for the army to deem him medically unfit for further service. Isaac was sent home to Australia and disembarked on 31 October 1917.

His great-nephew Lieutenant Colonel Russell Linwood, ASM later reflected:

“This wounding probably helped his survival as he was hit when in the Forming-Up Place and did not make it past the front trench… Having visited the battlefield recently and seen for myself the lay of the land, it is amazing our casualties were not even higher.”

The Linwoods

The Linwoods of Bundaberg were no strangers to service and sacrifice. Three sons of Hannah Linwood, a widowed mother in declining health, came forward during the Great War — each meeting a different fate.

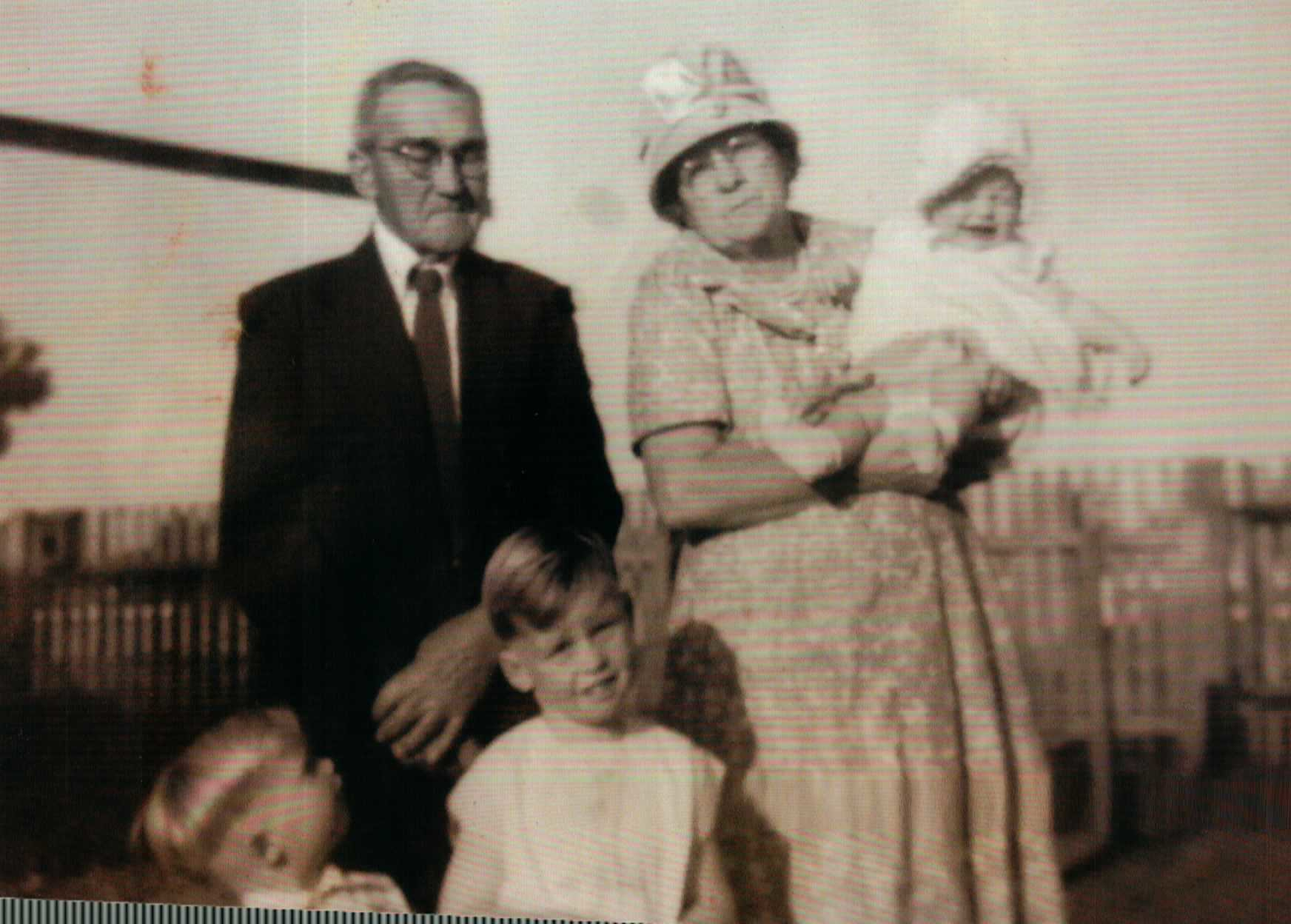

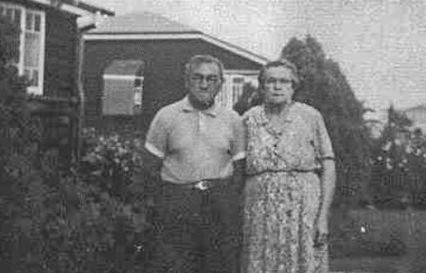

Isaac - wounded at the Battle of Fromelles was eventually repatriated to Australia in late 1917. Despite lingering health issues, Isaac built a stable life back home in Bundaberg. In 1918, he married Alma Victoria Alley (1897–1983), and the couple settled into post-war family life. Over the next two decades, they had five children and he lived until 1970.

Family at War

Percy - the youngest, joined the AIF in January 1916 at just 17. A saddler by trade and well liked in the Bundaberg district, he was assigned to the 52nd Battalion and landed in France in June 1916. On 14 August, barely two months after his arrival, Percy was killed in action near Mouquet Farm during the Battle of Pozières. His remains were later reinterred with military honours at Serre Road Cemetery No. 2. The death devastated his mother. According to local accounts, the sad news was delivered in person by Rev. H.C. Beasley, who broke it gently to Hannah at their home in Targo Street.

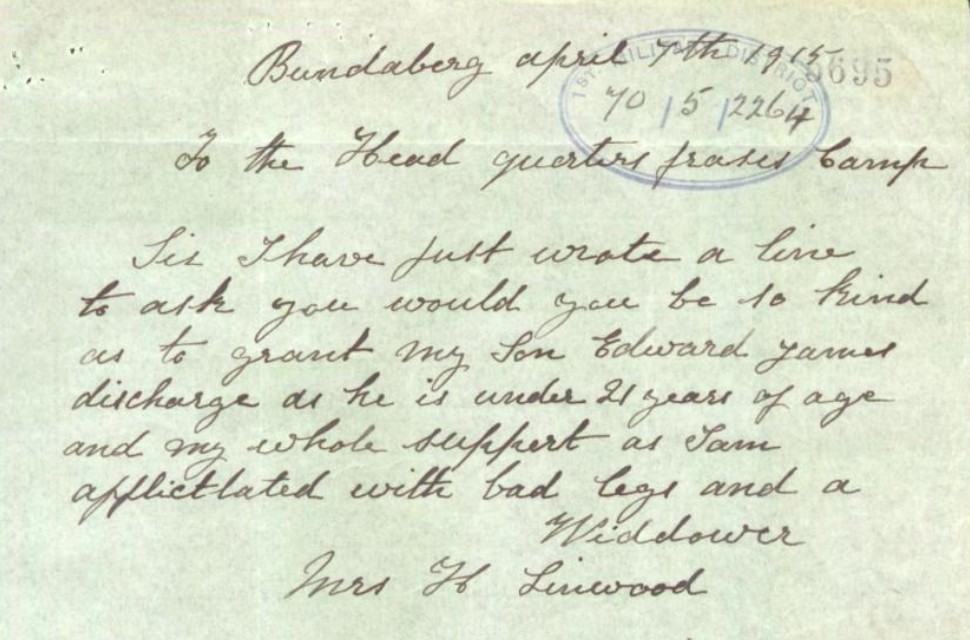

Edward - the middle brother, also attempted to enlist in early 1915. But their mother, then struggling with “bad legs” and without support, wrote a heartfelt plea to the military authorities:

“Sir, I have just wrote a line to ask you would you be so kind as to grant my son Edward James discharge as he is under 21 years of age and my whole support, as I am afflicted with bad legs and a widower.” — Mrs H. Linwood, Bundaberg, 9 April 1915

Her request was granted, and Edward returned home to care for her — honouring a different kind of duty. Edward would once again sign up in World War 2. But the Linwood family service did not end there. Their cousin, Private Edward James Linwood served with the 26th Battalion. He was wounded in action on 6 October 1917 during the Battle of Broodseinde, part of the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). He survived and returned to Australia.

And Edward’s brother, another cousin, Leslie Isaac Linwood, served with the 9th Battalion and later the 4th Pioneer Battalion. In September 1918, he was awarded the Military Medal and the Belgian Croix de Guerre for “conspicuous bravery under fire”

`"This N.C.O. was engaged with his Section on maintenance and repair of forward roads near Le VERGIEUR during the offensive operations on September 19th, 20th and 21st 1918. On several occasions his party was subjected to most trying hostile shell fire. Lance Corporal LINWOOD by his personal example of coolness and courage consistently held his men together on each occasion, and, displaying much energy and determination did excellent work under most trying conditions."

Source: 'Commonwealth Gazette' No. 135 Date: 11 December 1919' `

He returned home in 1919, wounded but decorated.

From battlefronts in France to sacrifice at home, the Linwood family’s war was not confined to one trench or one loss. It was a shared burden — of wounds, grief, honour, and resilience.

Family Remembers

Lieutenant Russell Linwood, ASM recalls:

Private Isaac Linwood was a great uncle, one of a very large family who, at the time WW I broke out had already lost their father. Not long after Isaac’s wounding at Fromelles, his younger brother 1676 PTE Percy Linwood 52 Bn was KIA attacking Mouquet Farm during the night 14/15 Aug 16. Hadn’t even made his 20th birthday. A third brother, Edward James, had also enlisted 11 Depot Bn, but being underage and without mother’s permission, he was discharged and sent home. Other male siblings did not enlist, having families to support. Fortunately, it would seem, for me at least. In my generation, I served almost 49 years in the Infantry so I have an intimate understanding of the operations these poor fellas took part in, the weapons and their effects.

In 2017, I took part in a military history tour of the Western Front as one of the advisors/military history specialists. Following the first day’s visit to where Isaac had been wounded at Fromelles with 31 Bn, I had the sobering experience and honour, as a senior army officer, of presenting great-uncle Percy’s medals (a replica set buried at his headstone in Sierre No 2 graveyard) to him 101 years after he was killed. By good fortune, someone who had read one of my books connected the dots and sent me one of his two medals from a private collection. I surmise that when issued eventually, those two medals went to my great grandmother who was a destitute widow trying to support an adult handicapped daughter, with little means of support. She possibly sold them to help make ends meet. Isaac’s medals have not been located in that family.

By coincidence, as a sniper instructor I had won the Australian national sniper pairs competition in 1988, called The Sniper/Billy Sing Trophy. It was named after 355 TPR/PTE William (Billy) Sing, DCM of 5th Light Horse/31 Bn. I also later had a small role in the repositioning of his pauper’s grave in Lutwyche Cemetery, Brisbane to a more prominent artifice more appropriate to our highest scoring sniper.

The 31st Bn Association duly invited me to join their ranks as an ‘Honorary’ member, so I did. That in turn led me, and my wife, to now attend 31 Bn events which sometimes include sub-proceedings that recognise descendants of the Fromelles tragedy. I also have an elder brother Kerry Linwood who actually served in 31 Bn in the 1970s.

So, thanks to extensive research capabilities of today, our entire family are now acquainted with what really happened to our WW I military ancestors, the first casualty of them being Isaac at Fromelles.

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).