George Henry POWER

Eyes brown, Hair brown, Complexion fresh

Pre War – George Henry Power

With sincere thanks to Peter Newton and other researchers for putting together George’s story.

George Henry Power was born in Colac, Victoria in October 1894. He was the second youngest of fourteen children born to schoolmaster, Geoffrey Joseph Power (b. Waterford, Ireland 1836 - d. Colac, Vic 1908) and his wife, Mary-Anne Sprague (b. Castlemaine, Vic 1856 - d. Colac, Vic 1902).

George was part of a large Irish-Catholic family who had been in the district since 1868. He was close to his siblings, particularly his older brother Geoffrey and his sisters; Harriet (Tot), Margaret (Meg or Maggie) and the youngest Power, Frances Mary (Mary).

He was educated by the Sisters of Mercy in Colac where he was regarded as highly spiritual, possessing a high intellect and, along with his bearing, reflected the utmost credit on his teachers.

On leaving school, George gained employment at the Colac post office where he had worked as a schoolboy messenger. He had strong telegraphic skills passing his 1908 exam at age 14 with high marks. George was a highly regarded member of the post office staff and a ‘favourite’ of the public.

George developed sporting talents, particularly in (Australian Rules) football where he was regarded as a ‘first class footballer’. He also developed an interest in the military while in the school cadets. This was a pathway into the local militia which he joined on leaving school. A number of his post office friends were also in the militia.

He was well respected in Colac as a member of the community and played a role in many community activities, particularly with the Hibernian Australasian Catholic Benefit Society (HACB), with which his siblings were also heavily involved.

Enlistment – George and Gerald

George followed the unfolding events in Europe with a keen eye and it’s no surprise that he enlisted almost immediately Australia entered the war in August 1914. He joined the 8th Battalion which was one of the first Australian infantry units raised, recruited primarily from country Victoria particularly Ballarat and surrounding areas.

As was common, George enlisted with an older brother (28-year-old Gerald). Another brother (Geoffrey) was listed as his next of kin as both parents were deceased. Given his telegraphic skills, George was assigned to HQ Company as a signaller. He was 19 years of age.

A number of George’s friends, also ‘Colac boys’, enlisted at the same time including Richard Bassett - another post office employee, a ’letter deliverer’ - and Alec Sitlington. Both Richard and Alec were the subject of a book ‘The Road to Fromelles’ (Dawn Peel and Andrew McIntosh, 2010). George is mentioned in many of Bassett’s letters home.

In October 1914, the 8th Battalion (including George and his brother, Gerald) sailed from Port Melbourne on HMAT Benalla bound for Albany, WA where they rendezvoused with transports from other states and New Zealand. HMAT Benalla sailed for the Middle East on 1 November. This of course was the ANZAC convoy, which carried the troops to the Middle East and who eventually landed at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915.

Gallipoli – George and Gerald

The 8th Battalion formed the second wave of the attack on the morning of 25 April 1915 and landed on the beach about 7.30 am.

The 8th was moved to Cape Helles during the first few weeks of the campaign in order to support the British and French action. The elder of the Power brothers, Gerald, suffered a gunshot wound to the hip in early May 1915. He was hospitalised and eventually promoted to corporal in August and sent home for family reasons on escort duty in September 1915. Gerald, then aged 29, was married with three sons and three step-daughters but the circumstances of the “family reasons” are not recorded on his AIF file.

In contrast, George remained at Gallipoli and was involved in some of the bloodiest fighting of the campaign, particularly in the battle of Krithia. George and his fellow signallers played a key role in running out (and repairing) telephone cable between the command post and the lines, always under heavy fire.

George saw action in the battle of Lone Pine in early August and later that month – like Gerald - was promoted to corporal.

Illness – George and Gerald

In November 1915, George was evacuated from the Peninsula, with his family being advised mistakenly that he was wounded in action. This caused a great deal of consternation and some anguish within the family, particularly his sisters.

The Army subsequently advised he had actually fallen ill with jaundice. He was later returned to the campaign and stayed until the withdrawal in December 1915.

By this stage, George was not a well young man, looking drawn, exhausted and much, much older than his 20 years. There is a stark and disturbing difference between the fit, confident young man smiling at Gallipoli and the ‘ghost’ photographed on Lemnos after the withdrawal. In fact, during re-training in Egypt, he again fell sick, was hospitalised and according to his friend Richard Bassett in a letter home, George ‘…was very lucky’. The family never knew just how ill George was at this time. Unfortunately, he wasn’t ill enough to be removed from the fighting.

Following his return to the division and more training, George became part of the newly formed 60th Battalion, was promoted to sergeant and became a Platoon Leader (XI Platoon, C Coy). The 60th was part of the 15th Brigade under the command of the legendary Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliott.

Back in Australia, George’s brother, Gerald, also suffered from illness though its cause (in hindsight) may not have been properly diagnosed at the time. ‘Shell shock’ or, in more modern terms, PTSD, may have been a current day consideration. His listed symptoms included “headache, nerves, nervousness, and a trifling degree of shock”. He also had a foot injury after he returned to Australia and walked with a limp. In 1918 he was discharged as medically unfit.

George at Fromelles

George sailed to France in June 1916 and in less than a month had met his fate along with many of his comrades during the infamous Battle of Fromelles. Of his home-town friends also with the 60th, Richard Bassett was wounded and Alec Sitlington killed.

The 60th’s point of attack was directly in front of the notorious machine gun position known as the ‘Sugarloaf’. Along with the 59th, who were positioned alongside, the 60th incurred the most casualties of any of the Australian battalions. Both battalions were virtually wiped out.

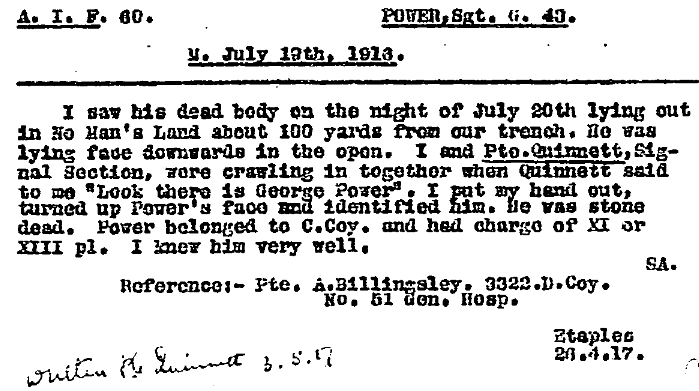

George’s platoon was in the first wave of the attack at 6.45pm and he was killed in the early evening of 19 July 1916. His body was never recovered from the field, but it was identified by members of his platoon on that night, about ‘100 yards’ from the Australian lines. He had managed to make it about the length of a rugby field before being cut down by the machine guns of the ‘Sugarloaf’.

George was 21 years and 9 months old when he died.

The Power Family at Home

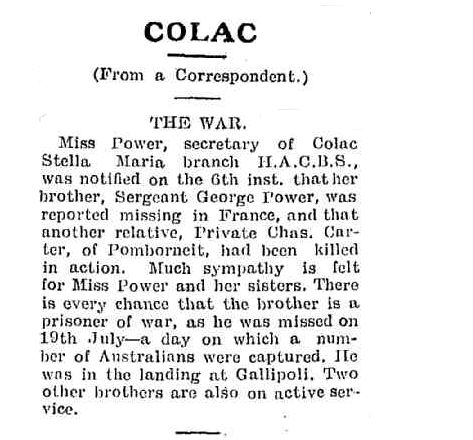

George’s family were understandably distraught at receiving notification that George was missing in action. Initially they held out some hope – as did most other families in the same situation - as “missing in action” was less definitive than having proof that he had been killed. Evidence from fellow soldiers and official reports took many months to filter through the mayhem of the Western Front. The family held onto a belief that he was wounded and lying unidentified in hospital or had in fact had been taken a prisoner of war.

Such was the traumatic family situation, that in early 1917, with still no news as to George’s fate, his sister Margaret (Meg/Maggie), resigned her head teacher’s appointment at St Joseph’s, Penshurst (a country town in south-western Victoria). Maggie, a well-respected teacher in the district, returned to Colac to help support the family.

During this same period, George’s older brother, Gerald, had returned home wounded – but nobody knew where he was.

In addition, the eldest of the Power brothers, 34-year-old Geoffrey, had enlisted in May 1916 and was now away fighting in France with the 46th Battalion. Family history confirms that their uncertainty created many, many issues for the family to deal with.

As was the case with many of the Fromelles ‘missing’, families were receiving reports through the Red Cross, returned servicemen and letters home that their loved ones were in fact dead. But with no official word from the Army, hope remained.

It was no different for the Power family.

By July 1917, George had been listed as missing for 12 months and the family had been receiving anecdotal reports of his death since November 1916. Having received a copy of the distressing account given by Pte Alexander Billingsley (pictured previously), Harriet wrote to the Army in July 1917. Her letter is an example of the strain and despair that was being felt by families after a year of not knowing their soldier’s fate. Particularly poignant is Harriet’s obvious struggle to keep control and maintain a sense of politeness and reserve in the correspondence following the devastating news:

‘…I have received the sad news of his death from three different soldiers at different times, I am enclosing the last letter I received from the (Red Cross) Information Bureau last Friday, it is most distressing to receive this news and one does not know whether it is true or not. Dear Sir, would you kindly let me know what you think about the matter….’

The Army simply replied that this news would be forwarded on, as it was, and eventually the final irrevocable confirmation in George’s short and honourable life had concluded.

When news of George’s death was finally confirmed, his hometown of Colac found it very difficult, with the Colac Herald (Melbourne Advocate) calling him:

“one of the finest specimens of manhood who have left Colac for the war”.

Regardless of the hyperbole, there is little doubt George was both loved and respected. In his short life, he left an indelible mark on all those with whom he came into contact.

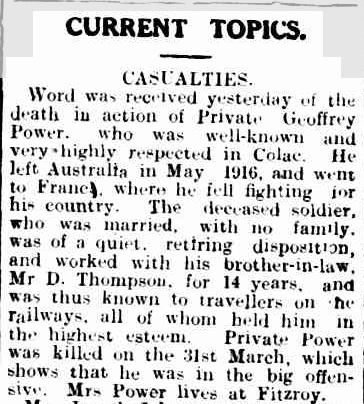

Sadly, George’s death was not the last blow for the Power family as news came through in April 1918 that Private 2244 Geoffrey Power had been killed in action on 31 March 1918. It is not known exactly where Geoffrey was killed, but it is most likely at Dernacourt, during the German spring offensive of 1918. Like George, Geoffrey too has no known grave.

Postscript and the Present Day

The Power family never spoke about the war, the loss of George and Geoffrey nor the tragedy of it all. Sure, they remembered, and the boys were never far from their thoughts, but talk about it – never. Family members kept to themselves when it came to any discussion on the war years. In later years, however, the youngest sibling, Mary, began to share stories with her children, which is where much of the anecdotal information originates.

It was only after researching service records, newspaper archives, and of course the many historical texts and articles relating to Fromelles, that a more complete picture emerged of what happened to George and his comrades, and of course the effect on their loved ones and the community.

Peter Newton, great nephew to George, has no doubt that his view of what happened to George has been coloured by the prevailing view of the battle itself: in that it was a badly planned, ill-conceived, murderous folly. He states:

“And in this regard, George’s death had much more to do with the ineptitude and conceit of those who planned and ordered the attack than the bullets from the German machine gun which ended his life.

I (and the family) have long held the view that his death was quite simply a waste, a murderous waste (even given the context that war is indeed licenced killing).”

Then….that all changed on a cold spring day in April 2017….

VC Corner Cemetery, Fromelles - 26 April 2017

Peter Newton describes the impact of visiting the battlefield more than a century later:

“Well, here we are, my wife Ann and I, standing at VC Corner, having just arrived from Amiens, where the day before we had attended the Anzac Day ceremonies at both the Villers Bretonneux memorial and the village itself.

We have found George’s name on the memorial wall (the first members of his family since his death to stand here), wiping away the tears (of mainly joy that we are here with him), we’re now looking out over the fields over which the 60th Battalion advanced. And feeling sadness, some anger and shaking our heads at the obvious futility of an attack over ground so flat, wide and open - they had no chance, no chance at all.

And yet…it is so very, very peaceful and calm here. So quiet and still except for birdsong and….laughter, lots of laughter! There are children riding their horses over small jumps at the farm next to the memorial. Their squeals of laughter, shouts of encouragement and sheer joy of life made me realise that this is what George died for. He died so that they could live, so that their parents and their parents before them could farm and live and be free to live their lives in peace and, by extension, so could all of us.

George and his comrades are here, right here in this place, we can feel them. They are at peace and they are loved. There is no pain here, only peace. They rest well and they rest surrounded by the love of their French famille. The love of le peuple Francais for these boys is overwhelming and humbling. We felt it at Villers Bretonneux and we feel it here now, it is real and tangible - Ils sont leurs fils.

My name is Peter Newton. I am the son of Joseph Newton, and he the son of Frances (Mary) Power, the younger sister of George Henry Power from Colac, Victoria, Australia. George, a native son of his native land who, aged 21 years and 9 months, was killed by a German machine gun in a farmer’s field in Fromelles, France on a warm summer’s evening in July 1916.

George Power and his comrades have left a legacy of which they would never have been able to comprehend. It has travelled and endured over 100 years to this very moment where, here on a cold spring day in April 2017, on the very ground where George’s short life ended, his family came to understand what le peuple Francais have known all along. It is a legacy of love, peace and life.

Thank you, George, thank you - always loved, never forgotten.

Et merci beaucoup a nos amis Francais. Merci beaucoup pour aimer George et ses camarades

Vive la France, vive l’Australie”

Request for Help

At the time of writing (April 2022) we are aware that the Army hold no DNA for this soldier and thus both mt and Y DNA donors are needed to “give this soldier his chance” at being identified. The Fromelles Association urge members of the Power and Sprague families to contact and register with the Australian Army (contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Additionally, we are desirous of obtaining any photos of George Power (1894-1916) or his brothers, Gerald (1886-1960) and Geoffrey (1881-1918). Please contact us if you can help.

DNA is still being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | George POWER 1894-1916 |

| Parents | Geoffrey Joseph POWER b. c1836 Waterford, Ireland d.1908 Colac, Victoria | ||

| and Mary Ann SPRAGUE 1856-1902 Colac, Victoria |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Maurice Power and Margaret Walsh, Ireland | ||

| Maternal | James SPRAGUE 1819-1893 and Ellen LYNCH 1832-1866 |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).