Frederick Hillgrove JACKSON

Eyes grey, Hair black, Complexion compexion fair

Frederick Hillgrove Jackson – “A Young Life Nobly Ended”

Can you help find Fred?

Frederick Hillgrove Jackson’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

Fred may be among these remaining 70 unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially for female line contacts of mother Esther nee Donkin, ancestors from Northumberland England.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for Walter, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Early Life

Fred was born on 26 January 1891 in Wallsend, a coal-mining suburb of Newcastle, New South Wales. He was the seventh of ten children born to labourer Robert Jackson, (1857-1928) and Esther née Donkin (1860-1942). Her Northumberland family had originally settled in Ballarat, Victoria before relocating north. The Jackson family later made their home at 127 Waratah Road, Broadmeadow, New South Wales where they were well known in the local community.

The Jackson household was large, six boys, four girls:

- George Robert Jackson (1878–1959) – married Ethel Moxey

- William James Jackson (1880–1966) – married Catherine Ethel Smith

- Alice M. Jackson (1881–1909) – married Mr. Robinson

- Henry Jackson (1882–1954) – married Mary Kirk Cooper

- Elizabeth Reid Jackson (1884–1962) – married Charles E. Bowrey

- Bertie Reid Jackson (1888–1974) – married Annie Standring

- Frederick Henry Jackson (c.1891–1916)

- Elsie May Jackson (1892–1927) – married Percival John Peterie (d. 1911); later married Charles Norman King

- Sydney Harold Jackson (1895–1968) AIF – married thrice.

- Florence Matilda Jackson (1899–1986) – married Albert Samuel Newey

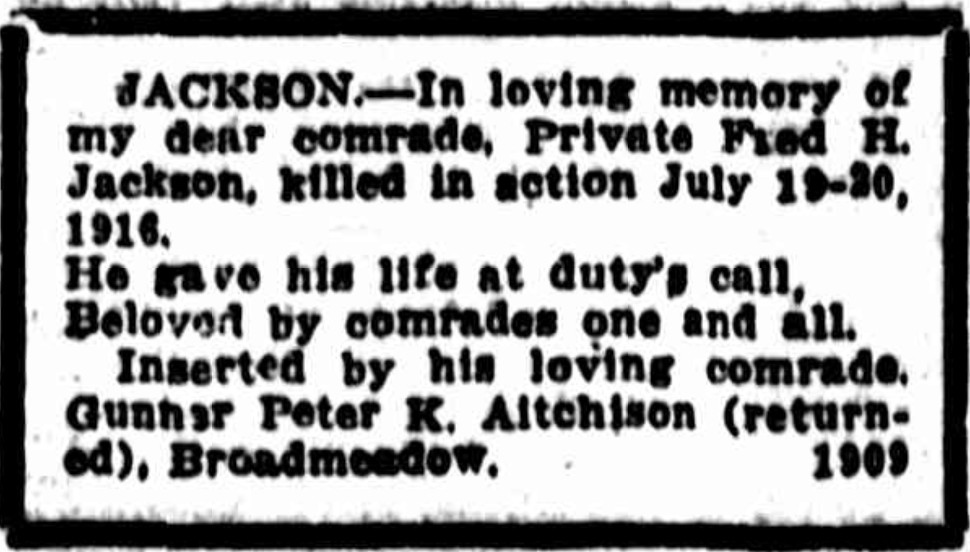

Fred attended The Hamilton Superior Public School and after finishing his education was employed as a railway fireman, a physically demanding role that involved maintaining steam engine boilers and shovelling coal. Fred’s closest friend was his next-door neighbour, Peter Kerr Aitchison, with whom he shared a special bond. Peter became a miner and also served in France.

Fred and Peter’s enlistment sparked pride throughout the Hamilton-Broadmeadow community - representing the strong working-class spirit of Broadmeadow — young men from a proud mining and railway district who answered the call.

Off to War

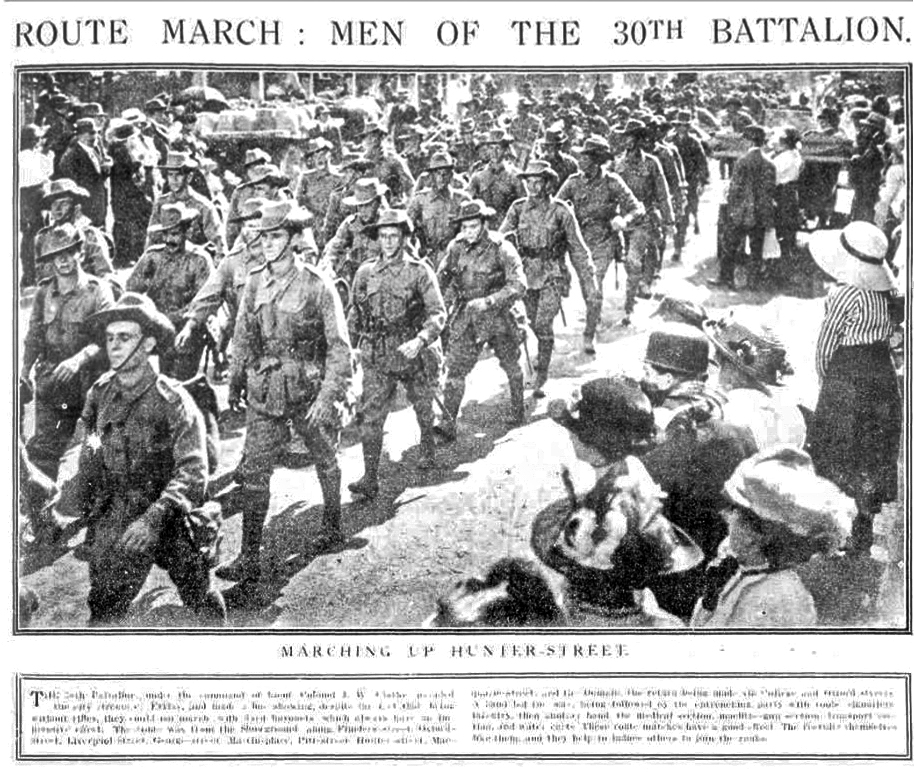

Fred enlisted on 27 July 1915 in Newcastle — just one day after friend Peter Aitchison. His brother Sydney also enlisted, in 1917, and returned home safely in 1919 after service as a sapper with the Engineers and 5th Battalion. Fred was assigned to the newly formed 30th Battalion, B Company. Peter was orignally assigned to A Company, but was transferred to B Company shortly after they sailed from Australia – together again. Training commenced in the Liverpool camp, but in September they moved to the Royal Agricultural Show Grounds in Moore Park, Sydney. There were numerous reports of their activities in the papers.

Before departing, the pair were honoured at a farewell gathering at Peter’s home in Young Street, Broadmeadow, attended by a large number of friends and relatives:

“Private P.K. Aitchison, who was on final leave, was given a send-off at his residence, Young-Street, Broadmeadow, by a large number of relatives and friends. Private Fred Jackson was a guest...Mr. Gilmore… said he felt confident that they would both do their duty, and wished them both a safe return.”

The boys left Sydney for Egypt aboard HMAT A72 Beltana at 3.30 PM on 9 November 1915. Their trip was uneventful and they disembarked in Egypt on 11 December. Their first seven weeks were spent at Ferry Post guarding the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army and continuing their training. February and March were spent at the 40,000 man camp at Tel-el-Kebir, 110 km northeast of Cairo. However, they were separated on 15 March as Peter was moved to the 15th Field Artillery Brigade and then just a week before the battle, to the 5th Divisions’ Howitzer Brigade.

This move reflected the AIF’s ongoing restructuring and preparation for warfare on the Western Front. Artillery was becoming the defining weapon of trench warfare, and Peter, now a gunner, would be responsible for manning the heavy field guns used to bombard enemy positions and support infantry assaults. For much of April and May Fred was back at Ferry Post, including some time in the front-line trenches there. There were the usual complaints of the heat, water supplies and flies.

The 30th Battalion left Egypt for the Western Front on 16 June 1916 on HMAT Hororata and arrived in Marseilles on 23 June. After landing, they were immediately entrained for a 60+ hour train ride to Hazebrouck, 30 km from Fleurbaix. They arrived on 29 June and then encamped in Morbecque.

Private F.R. Sharp (2134) wrote home:

“From the time we left Marseilles until we reached our destination was nothing but one long stretch of farms and the scenery was magnificent.” “France is a country worth fighting for.”

The area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. Training now included the use of gas masks and they also would have heard the heavy artillery from the front lines. On 8 July they were headed to the front lines, first to Estaires, 20 km and the next day 11 km to Erquinghem, where they were billeted at Jesus Farm.

They got their first ‘taste’ of being in the front lines at 9.00 PM on 10 July. Peter’s new role placed him in direct support of Fred’s 5th Division’s operations — including the artillery barrage that would precede the infantry assault on 19 July.

The Battle of Fromelles

On 8 July they were headed to the front lines, first to Estaires, 20 km and the next day 11 km to Erquinghem, where they were billeted at Jesus Farm. They got their first ‘taste’ of being in the front lines at 9.00 PM on 10 July. A week later, they got orders for an attack, but it was postponed due to the weather. In his final letter home Charles Albert Woods (2194 30th Bn) summed up the situation he found himself in:

“Since writing last we have shifted from ‘somewhere in France’ to ‘somewhere else in France,’ and are now in the trenches. Whilst writing this the shells are whistling over our heads a ‘treat.’ We are all provided with steel helmets to lessen the danger of being hit in the head with shrapnel, and also with gas helmets, to put on while a gas attack is being made on us.”

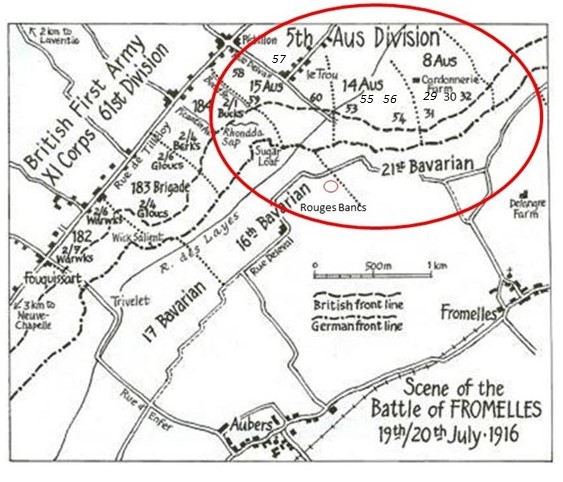

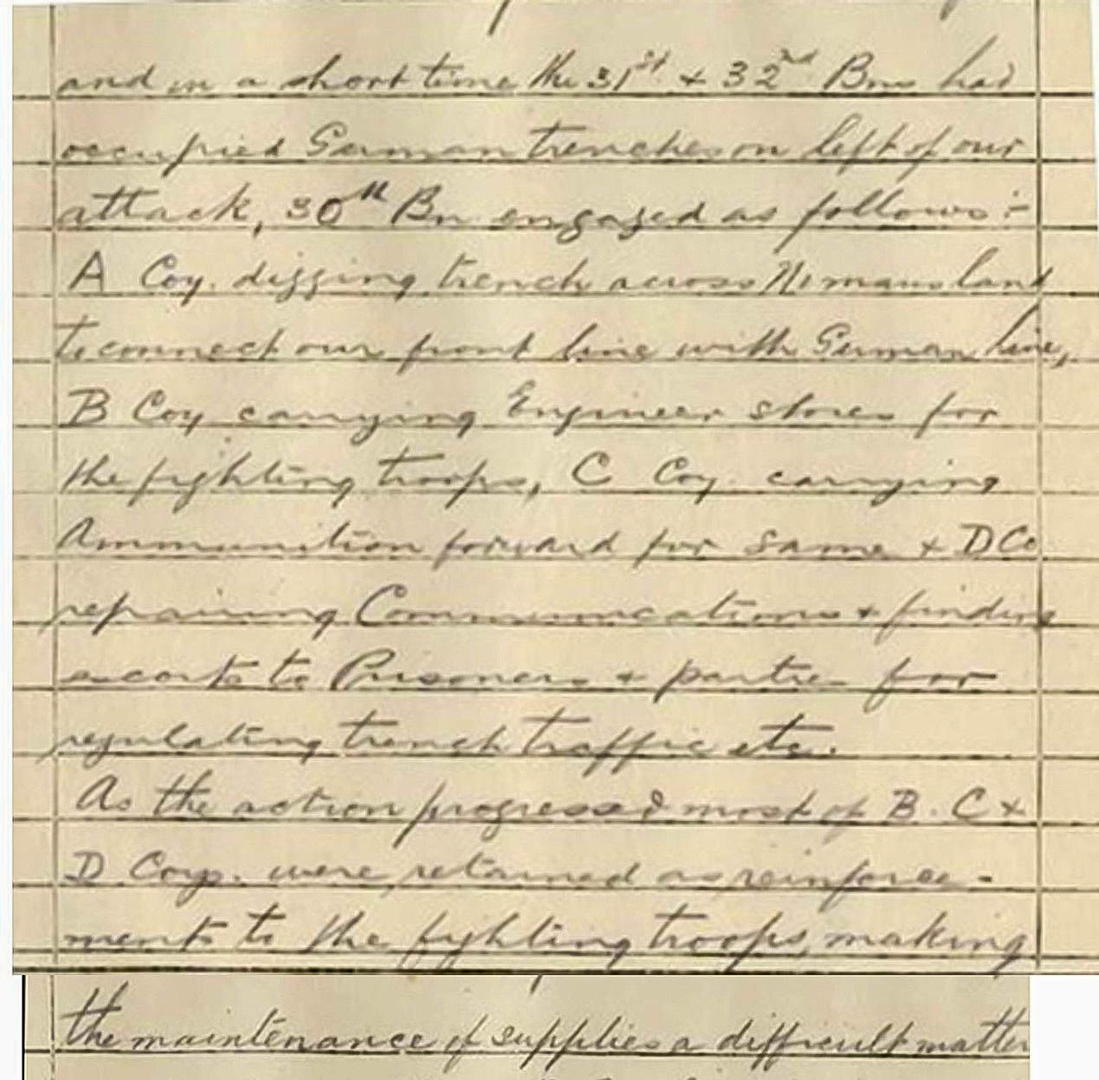

Then, on 19 July, the 29 officers and 927 other ranks of the 30th Battalion were into battle. The overall plan was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The 30th Battalion’s role was to provide support for the attacking 31st and 32nd Battalions by digging trenches and providing carrying parties for supplies and ammunition. They would be called in as reserves if needed for the fighting.

On 19 July, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. The 32nd’s charge over the parapet began at 5.53 PM and the 31st’s at 5.58 PM.

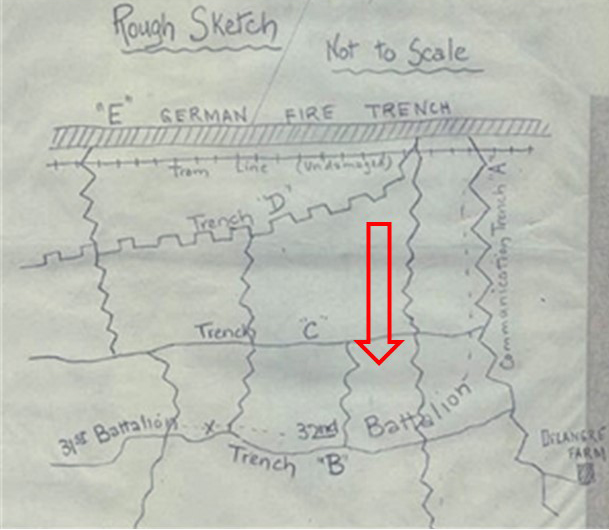

There were machine gun emplacements to their left and directly ahead at Delrangre Farm and there was heavy artillery fire in No-Man’s-Land. The initial assaults were successful and by 6.30 PM the Aussies were in control of the German’s 1st line system (Trench B in the diagram below), which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

Source - AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

While their role was to be in support, commanders on scene made the decision to use the 30th as much-needed fighting reinforcements. A necessary act, but it had consequences as it interfered with the planned flow of supplies.

By 8.30 PM the Australians’ left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and they were told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source - AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

When the 30th was formally called to provide fighting support at 10.10 pm, Lieutenant-Colonel Clark of the 30th reported:

“All my men who have gone forward with ammunition have not returned. I have not even one section left.”

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine-gun fire from behind from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map).

Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, portions of the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers. At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties.

Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance the 31st could offer was with rifles:

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

By 10.00 AM on the 20th, the Germans had repelled the Australian attack and the 30th Battalion were pulled out of the trenches. The nature of this battle was summed up by Private Jim Cleworth (784) from the 29th:

"The novelty of being a soldier wore off in about five seconds, it was like a bloody butcher's shop."

Initial figures of the impact of the battle on the 30th were 54 killed, 230 wounded and 68 missing.

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield.

The ultimate total was that 125 soldiers of the 30th Battalion were either killed or died from wounds and of this total 80 were missing/unidentified.

After the Battle

Multiple witnessess stated that Fred Jackson was killed and last seen in No Man’s Land. Captain John A. Chapman, 30th Battalion:

“He was seen in No Man’s Land killed and his identification disc was taken off and handed to his O.C. Coy. (Major Frederick Street).”

Private H.W.L (William) Climo (1173) stated:

“His disc was brought in from No Man’s Land by an A. Coy party. I saw it. He was a friend of mine.”

Not only was his ID tag recovered, but other witnesses also said his body had been recoverd and even that his grave had been seen behind the lines. Private Ernest Heeger (443) wrote:

“Corporal Wilson, B Company, wrote me that they got Jackson’s body out in No Man’s Land two days after, and brought it in.”

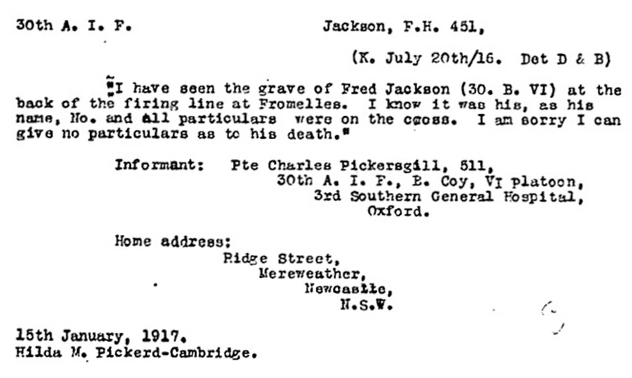

And one witness, Private Charles Pickersgill (511), claimed he had seen a marked grave bearing Fred’s name and details behind the firing line:

“I have seen the grave of Fred Jackson (30. B. VI) at the back of the firing line at Fromelles. I know it was his, as his name, No. and all particulars were on the cross.”

However, Private Percy Milgate (495) added an alternate insight into what may have happened with Fred’s burial:

“A volunteer party from another Coy. went out next night collecting discs and pay books from the bodies and Jackson’s disc and pay book were brought in. Some bodies were brought in some time after the discs and pay books had been taken from them and therefore were buried without being identified. Jackson’s body may have been among them.”

Despite these accounts, Fred’s remains were never formally recovered or identified. He has no known grave.

Family, Friends and Community Mourn Fred’s Death

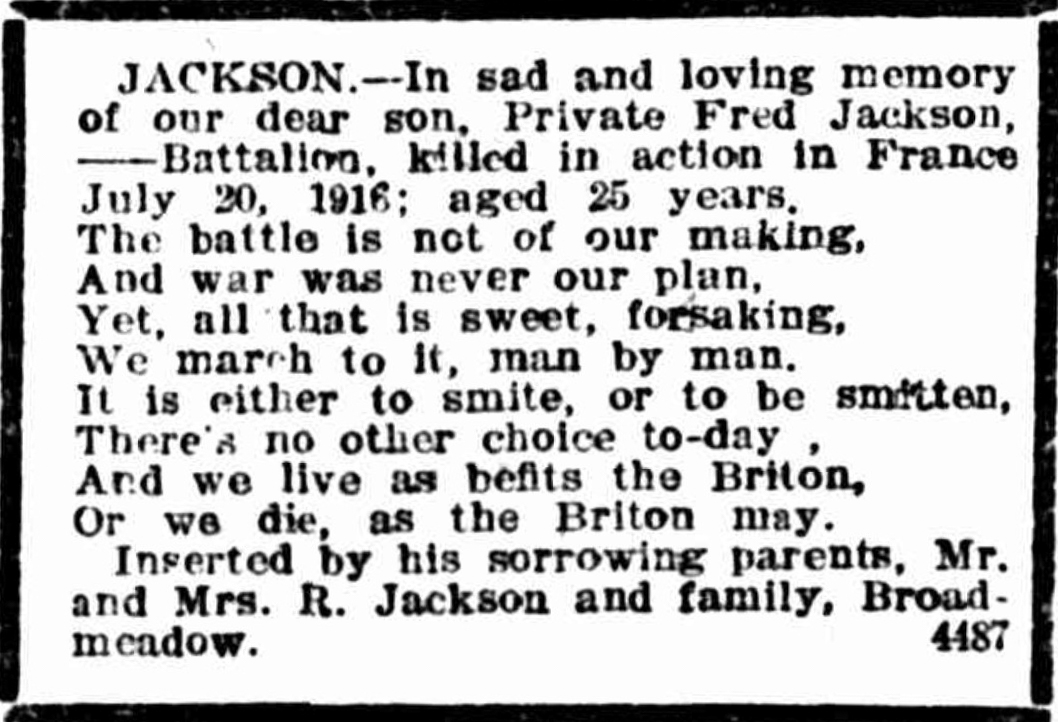

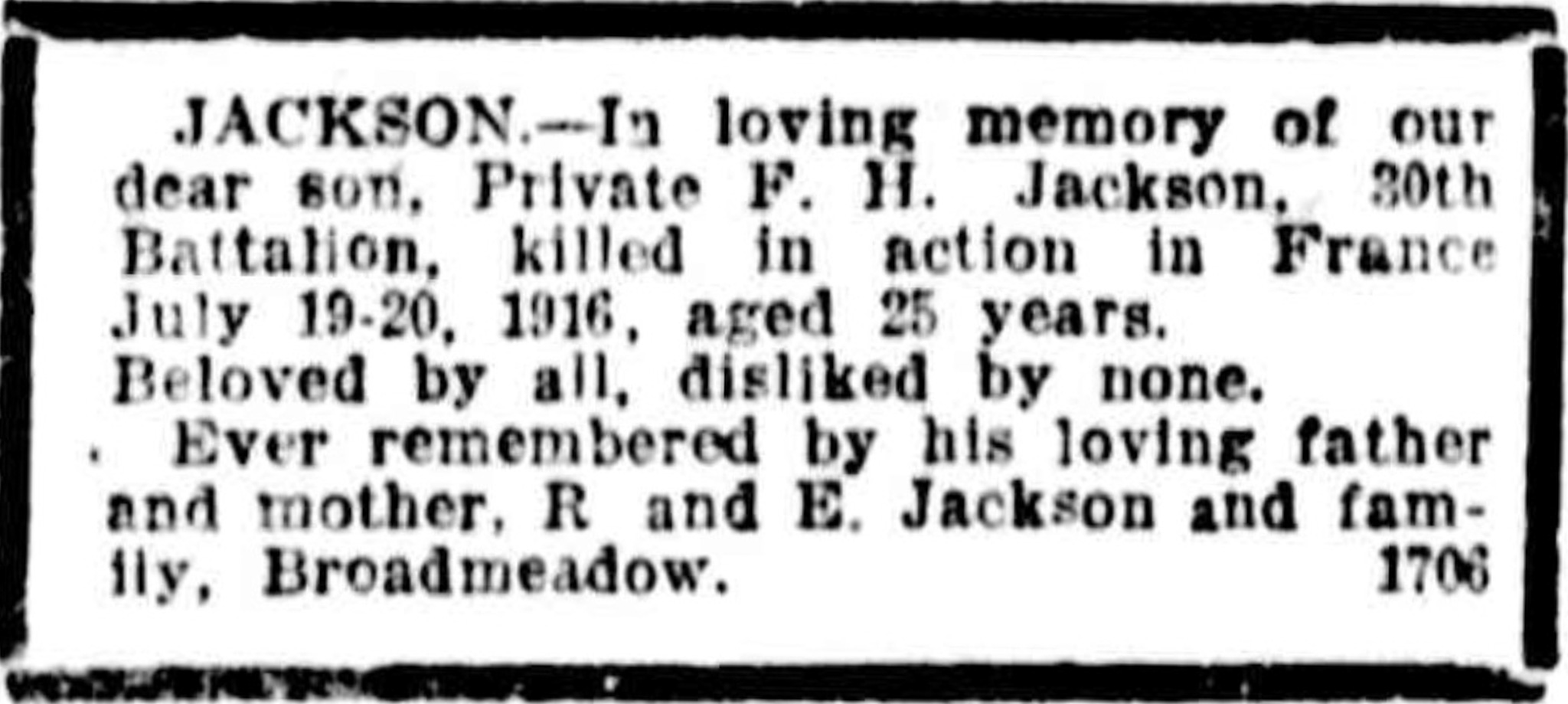

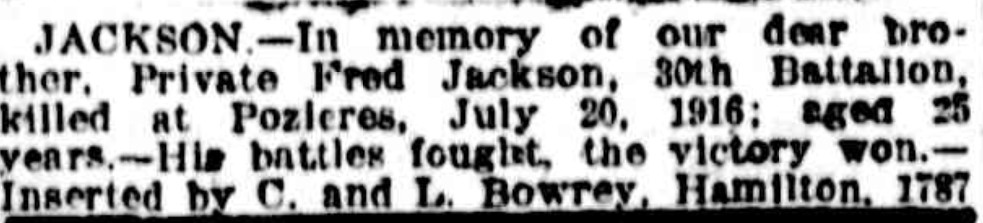

Fred was remembered with immense affection and sorrow by his extended family, friends, and mates from the Hunter region. On the first anniversary of his death, there were ten memoriam notices in the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, showing just how deeply his loss was felt across communities.

A selection of the other tributes:

“A young life nobly ended.”

“Life’s highest mission he fulfilled, All he had to give he gave.”

“In the dawn of a splendid manhood, When the tide of his youth ran high, with courage and hope in his bearing, He waved us a last good-bye.”

“He marched away so bravely, His young head proudly, held, His footsteps never faltered, His courage never failed, He died that we may live.”

“Somewhere in France he is lying, Somewhere in France he fell, Far away from the shores of Australia And the ones that loved him well.”

“One whom in life we admired, In death we sadly miss. He died as he lived – nobly.”

Over the years, Fred’s family continued to honour his name through published notices. In 1919, three years after his death, his parents and siblings remembered him with quiet sorrow and verse

Also, in 1921, five years after his best mate was killed, there was a further tribute from Peter.

In January 1917, a Roll of Honour was unveiled at the Presbyterian Hall in Hamilton by the Rose of Hamilton Lodge of the Grand United Order of Oddfellows, listing 50 members who had enlisted for service in the Great War. Among them were Private Frederick Hillgrove Jackson, noted as killed in action, and his friend Peter Kerr Aitchison, who had enlisted alongside him in 1915:

“We hereby place on record the names of members who, for love of country and a just cause, enlisted for active service during the Great War... and we hereby express, on behalf of our order, the high esteem in which we hold them for their gallantry and heroism.”

The roll was decorated with Allied flags and placed prominently near the lodge’s merit boards — a lasting tribute from the Hamilton community.

On 18 September 1917, Fred was honoured at a special presentation hosted by the Hamilton Soldiers’ Presentation Committee. Held at the Broadway Picture Palace in Broadmeadow, 39 medals were distributed to soldiers and their families. Fred and Peter were among the fallen remembered by name. Alderman Brien, the Mayor of Hamilton, said:

“Hamilton was justly proud of its soldiers. Unfortunately, no fewer than five had been killed. It gave him pleasure to be in the position of honouring the district's heroes by presenting medals to their relatives.”

Fred was awarded the 1914-15 Star Medal, the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll.

He is commemorated at:

- VC Corner Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles (panel 2)

- Hamilton Municipal District Roll of Honour

- Hamilton Superior Public School Roll of Honour

- Rose of Hamilton Lodge, G.U.O.O.F. Roll of Honour

Finding Fred

Fred’s remains were not recovered, he has no known grave. After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including 26 of the 80 unidentified soldiers from the 30th Battalion.

We welcome all branches of Fred’s family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification and some have come forward. However, if you know anything of family contacts, especially for female line contacts of mother Esther nee Donkin, ancestors from Northumberland England, please contact the Fromelles Association. We hope that one day Fred will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Fred’s story.

Family Tree, Broadmeadow, Newcastle area, NSW, and before that mother’s Donkin line from Northumberland England.

| Soldier | Frederick Hillgrove Jackson (1891–1916) France |

| Parents | Robert Jackson (1856–1928) and Esther Donkin (1860–1942) |

| Siblings | George Robert Jackson – married Ethel Moxey | ||

| William James Jackson – married Catherine Ethel Smith | |||

| Alice Maud Jackson – married Mr. White | |||

| Henry Jackson – married Mary Kirk Cooper | |||

| Elizabeth Reid Jackson – married Charles E. Bowrey | |||

| Bertie Reid Jackson – married Annie Standring | |||

| Elsie May Jackson – married Percival John Peterie; later married Charles Norman King | |||

| Sydney Harold Jackson – married three times | |||

| Florence Matilda Jackson – married Albert Samuel Newey |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Daniel Jackson (1814–1876) and Sarah Mather (1819–?) | ||

| Maternal | William Donkin (1827–1904) and Elizabeth Reed (1833–1898) |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).