Walter Arthur POTTER

Eyes blue, Hair dark brown, Complexion fresh

“Mates, Brothers, Prisoners - The Story of Walter Potter and George Lukeen”

Early Life

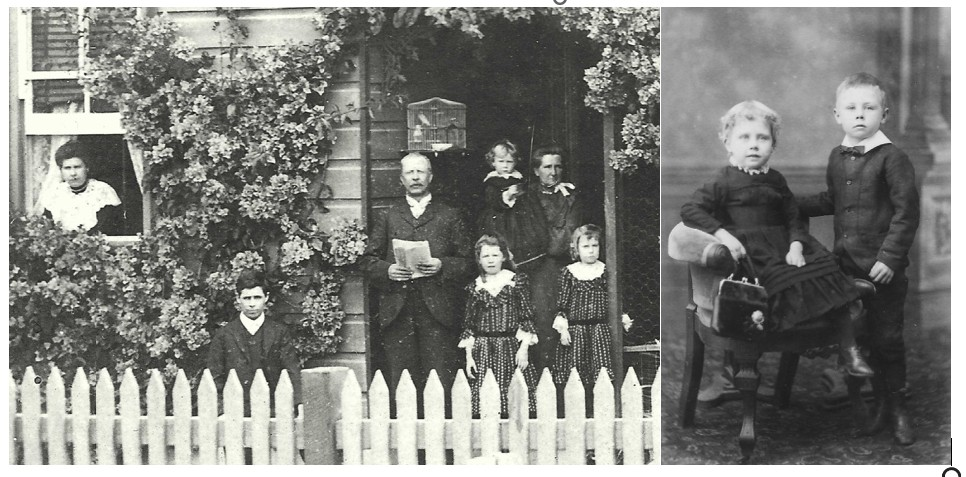

Walter Arthur Potter was born on 10 November 1884 in Bathurst, New South Wales, the eldest son of Benjamin George Potter and Rachel Cheney. His father was a long-serving NSW railways stationmaster, posted around the state before the family eventually settled at “Benray,” Good Street, Granville. Walter grew up in a large and busy household, surrounded by several siblings:

- Charles William (1881–1903),

- Mabel Letitia (1883–1919),

- Samuel George (1886–1928),

- Alfred Henry ‘Alf’ (1888–1966),

- Anne Mary Prudence (1890–1893),

- Dora Grace ‘Gracie’ (1897–1957),

- Vera Joy (1901–1981)

- and Dorothy Isabel (1904–1975).

Walter was descibed by his acquaintances as having been a most up-right man, a very straight goer, and a genial and popular companion. Early in life he had fractured his arm that never set correctly.

George Mathew Lukeen had a very different childhood, but he later became one more of the Potter ‘clan’. He was born on 15 May 1884 in Teralba, New South Wales, the son of Simon Lukeen and Mary M. Lukeen (née unknown). They also had two other children, Mathiea and Rock, but Rock died young.

His father was an Austrian born seaman-turned-labourer. Unfortunately, he drowned in a boating accident in 1895 when George was just eleven. His mother had serious health issues and was in the Gladesville Asylum. She eventually died of natural causes on 18 February 1909, reportedly leaving an estate of £700.

Following the death of his father and with his mother being in Gladesville Asylum and no other family, George and his sister were in need of protection. He was admitted to the Vernon and the Sobraon Training Ship for boys on 10 March 1896, a state-run reformatory and nautical school moored in Sydney Harbour, and Mathiea was placed in the Shaftsbury Reformatory. George was recorded as being very intelligent and sharp.

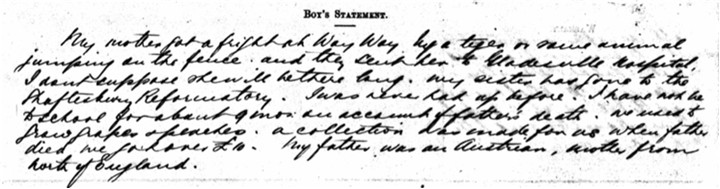

The twelve year old George made the following statement about his family when he was admitted to protection:

My mother got a fright at Woy Woy by a tiger or new animal jumping on the fence; and they committed her to Gladesville Hospital.I don’t suppose she will return any.My sister has gone to the Shaftesbury Reformatory.I was never bad up before. I have not been to school for about 9 months on account of father’s death. We used to grow grapes and peaches… – a collection was made for us when father died we gathered 10 pounds.My father was an Austrian, mother from north of England..

Records subsequently show that his sister Mathiea died in Parramatta in 1896.

At some point after his mother’s death in 1909, George was taken in by the Potter family, a connection that would shape the rest of his life. Newspaper reports from the time confirm that he was effectively adopted into the household:

“When in his early youth Private Lukeen’s mother died and left him an orphan at Woy Woy, Mr. and Mrs. Potter took him into their home, as he and their son, Private Potter had throughout their boyhood been great chums.”

This informal adoption turned childhood friendship into brotherhood. George’s enlistment papers later listed Mabel Letitia Potter — Walter’s sister — as his next of kin, underscoring just how deeply integrated he was into the Potter family. He was working as a carpenter and fisherman before the war and was well known around the Hawkesbury district.

Off to War

On 16 August 1915, Walter and George enlisted side by side at Holsworthy, joining the 14th Reinforcements of the 13th Battalion.

The Cumberland Argus noted the depth of their bond, reporting that when George heard Walter was going to the war, he:

“at once came to Sydney and enlisted with him, and they left together, attached to the same regiment, as brothers-in-arms.”

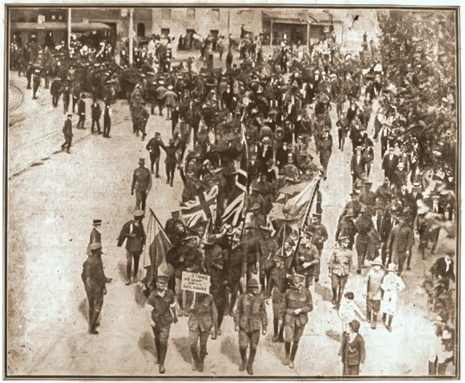

In October 1915, the Granville community honoured the two men who were about to depart in a civic presentation, presenting them with watches and fountain pens. While they were still in camp, the Liverpool Camp riot erupted on 14 February 1916, but the Cumberland Argus reported how both men refused to join in:

“(Walter) was in camp with his adopted brother, Private George Lukeen (who also sailed with him) when the big riot broke out at Liverpool Camp, and because they would not join in with the rioters they were both threatened that they would be ‘done for.’ They were to have sailed that day, but it was not till two days afterwards that the contingent was taken quietly to the transport and sent silently and quietly away to do their bit to uphold the flag…”

On 16 February 1916, just two days after the riot, Walter and George embarked from Sydney aboard HMAT Ballarat A70 for a five week trip to Egypt. They disembarked on 22 March. Their arrival was during a period of the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five, and, with the influx of new recruits, major reorganisations were underway. The 54th Battalion had been formed in mid-February 1916 at the Tel-el-Kebir camp, about 110 km northeast of Cairo. The camp contained about 40,000 men - Gallipoli veterans and the thousands of reinforcements arriving regularly from Australia.

The 54th was to be made up of Gallipoli veterans from the 2nd Battalion, most of whom were from New South Wales, and new arrivals from New South Wales, now to include mates Walter and George, who were assigned here on 1 April. The 54th was at Ferry Post at that time, guarding the Suez Canal and continuing their military training. The following weeks were spent near the Suez at Katoomba Heights, about eight miles from the Canal, where the 54th took turns occupying front-line trenches, wiring defences, and carrying out patrols. The men became accustomed to trench life and continued their training in preparation for movement to the Western Front. The call to the Western Front to join with the British Expeditionary Force came on 20 June and the 982 soldiers of the 54th Battalion left Egypt.

They sailed on the Caledonian for the 10 day trip to Marseilles via Malta. After disembarking in France they immediately entrained for a three-day train trip to Hazebrouck, 30 km west of Fleurbaix in northern France. The long train journey north took them through the lush countryside of France — a stark contrast to the sands of Egypt. By 2 July the Battalion was billeted in barns, stables and private houses in nearby Thiennes for a week. Training now included the use of gas masks and exposure to the effects of the artillery shelling. It was hoped that these tests would “inspire the men with great confidence”

Source: AWM4 23/71/6 54th Bn War Diaries July 1916 page 2

On 10 July they moved to Sailly sur la Lys and on 11 July they were into the trenches in Fleurbaix. The health and spirit of the troops was reported as good. After a few days getting exposed to the to the routines of life in the trenches, they moved back to billets in Bac-St-Maur. This area near Fleurbaix which was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long.

Major Roy Harrison wrote home on 15 July. With his Gallipoli experience, the tone in this letter was certainly circumspect for the upcoming battle:

`“The men don’t know yet what is before them, but some suspect that there is something in the wind. It is a most pitiful thing to see them all, going about, happy and ignorant of the fact, that a matter of hours will see many of them dead; but as the French say ‘C’est la guerre’.”`

The Battle of Fromelles

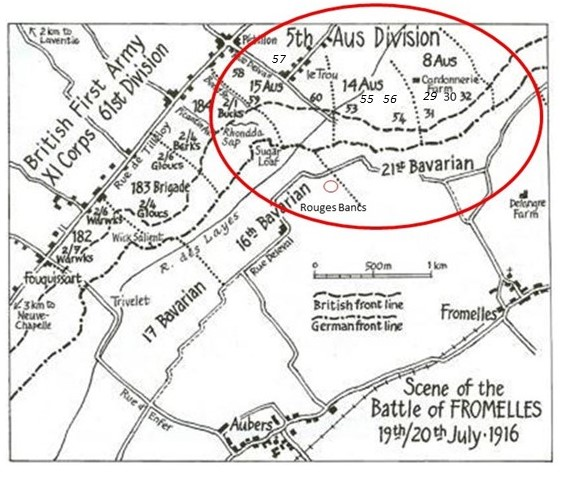

The overall plan was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The main objective for the 54th was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the “Sugar Loaf”’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the 54th and the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfilade fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction.

As they advanced, they were to link up with the 31st and 53rd Battalions. The main attack was planned for 17 July, but heavy rain delayed the operation. The weather soon improved and by 2.00 PM on 19 July they were in back in the trenches, ready for their first major action on the Western Front. On 19 July, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties.

At 5.50 PM they began to leave their trenches. They moved forward in four waves– half of A & B Companies in each of the first two waves and half of C & D in the third and fourth.

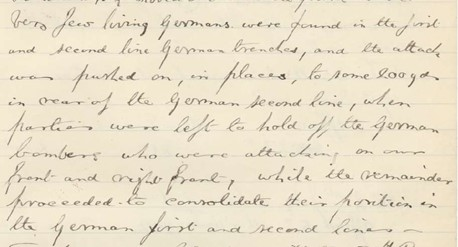

The first waves did not immediately charge the German lines, they went out into No-Man’s-Land and lay down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift. At 6.00 PM, the German lines were rushed. The 54th were under heavy artillery, machine-gun and rifle fire, but were able to advance rapidly. The 14th Brigade War Diary notes that the artillery had been successful and “very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches”.

Some of the advanced trenches were just water filled ditches which needed to be fortified to be able to hold their advanced position against future attacks. They pressed forward nearly 600 yards, linking with the 53rd Battalion on the right and 31st and 32nd on the left, holding a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm. But on the right flank, the situation had collapsed. The 60th Battalion had been unable to advance due to devastating machine-gun fire from the Sugar Loaf, leaving the 54th’s flank exposed. Lt-Col Cass, commanding the 54th, reported that by 2.20 a.m., the enemy was attacking along the road past Rouge Bancs.

Lt-Col Cass reported that after a counter attack the 53rd were not aware that their flank was no longer protected, allowing the Germans to get behind them and that Australians were being captured. Lt-Col Cass sent a party of 54th men forward to support the line:

“They ran forward with the bayonet and drove the enemy back about 50 yards.”

Despite repeated appeals for artillery support, the position became untenable. At 6.30 a.m. on 20 July, the 54th received orders to withdraw. The retreat was chaotic and exposed to fire; many wounded men were left behind. He later wrote:

I saw scores of men badly wounded and no help at hand to bind them up.

With the heavy losses and the German counterattacks, the Australians were eventually forced to retreat, but now having to get through the Germans who were also BEHIND them as a result of the exposed right flank. By 7.30 AM on the 20th, the survivors had fallen back to Bac-St-Maur, nearly 5 km from the front. In this very short period of time, of the 982 men who had sailed from Egypt just a month before, the first casualty returns reported 73 killed, 288 wounded and 173 missing.

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. Ultimately, 172 men of the 54th Battalion were killed, and 102 of those remain missing to this day.

After the Battle

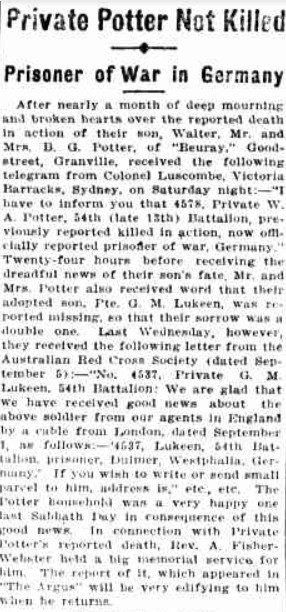

According to initial reports, Walter was missing, killed in action, and George, the adopted son of the Potter family, was missing. For weeks the family back in Australia were left in limbo — with no further confirmations of both of their ‘sons’’ fates. With the news that Walter had been killed, an “impressive” memorial service was held at the Granville Congregational Church on 20 August, 1916:

“the building was not large enough to accommodate all who wished to take part in the servive .”

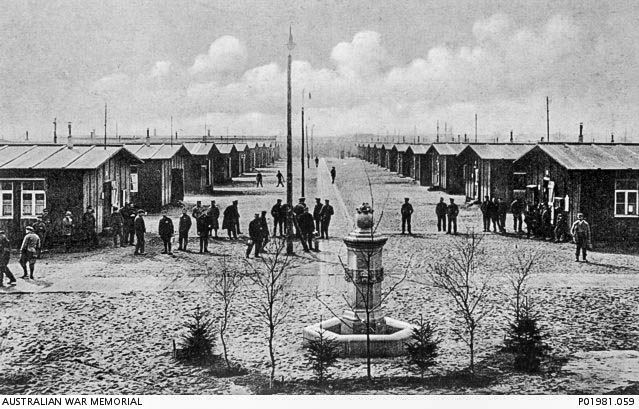

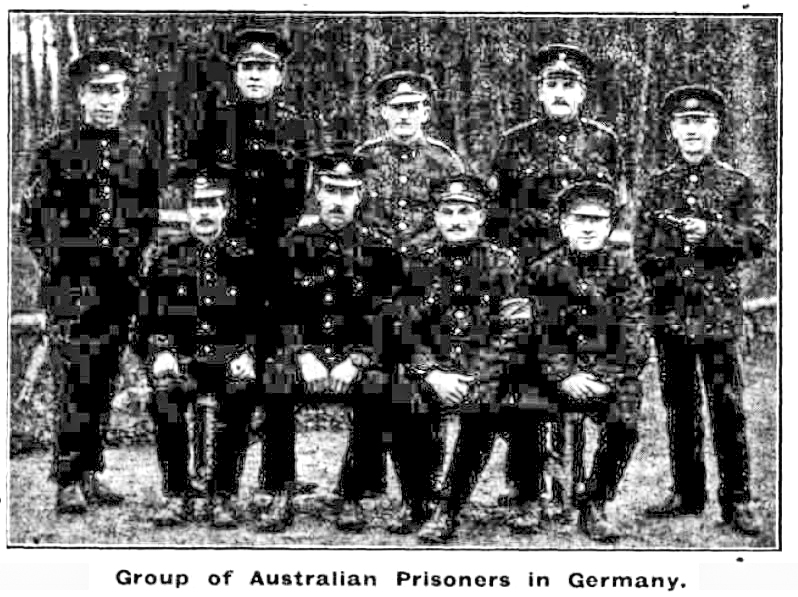

More news on George arrived on 5 September, this time good news (considering) - George was a prisoner of war at Dülmen, Westphalia:

”The Potter household was a very happy one last Sabbath Day in consequence of this good news.”

Then, another telegram arrived on 6 September - Walter was not dead after all! He too was a prisoner in Germany, captured during the same action:

“After nearly a month of deep mourning and broken hearts... Mr. and Mrs. B. G. Potter, of ‘Benray,’ Good-street, Granville, received the following telegram... ‘I have to inform you that 4578, Private W. A. Potter... previously reported killed in action, now officially reported prisoner of war, Germany.”

While many families were often never given such ‘good’ news, the Potters’ grief turned — cautiously — into hope. In Granville, the memorial service that had already been held for Walter now took on an unexpected poignancy. And for George, more news continued, with the Red Cross confirming his whereabouts and a letter from George from Germany eventually reached home.

Prisoner of War - Walter

After their capture, Walter, George and the other prisoners were marched to Lille, where they spent the night in a fortress. They were then moved to Douai and held for ten days in a storehouse “alive with vermin.” From there they were transferred to Dülmen in Westphalia.

Although George had initially been captured alongside Walter, the two were later separated, but exactly when is unknown. After returning to Australia, Walter described his experiences in a newspaper interview:

‘It was at Fleurbaix that I fell into the hands of the enemy. I and ten others were taken. We occupied a trench in the first line, and the Germans made a raid on us. There was a bit of a fight, in which I was severely wounded in the arm. The reason for capitulating was that our bombs would not explode and the ammunition was bad. There was no other course open to them but to throw up our hands. We were completely surrounded. I was captured shortly before 9 a.m.’

After surrendering, Walter said

‘The men were searched for papers so as to discover their rank. After surrendering we were ordered to take off and hand over the whole of our equipment. I had a pocket diary in which I had made entries since the time of leaving home. I was afraid they would get hold of it, so when I had an opportunity I sat on it and did my best with my uninjured hand to tear the leaves into little pieces and stamp them with my foot into the mud. For my pains I received a bang on the back with the butt end of a rifle and then a ‘tickler’ in the ribs from a bayonet.’

Then, Walter was interrogated by a German officer -

‘Which battalion did you belong to?— The 45th. What was your captain's name?— Captain Brown. Who was your lieutenant?— Lieut. Smith. Which company were you in?— E company. What was the number of your platoon?— No 7.The officer then said: ‘Private Potter, you are a d— liar.’I looked him up and down as if surprised at such a remark.He then said: ‘You belonged to the 54th Battalion, your lieutenant is named Saddler, you have only three companies, A, B and C, and your platoon was No. 2.’I asked him why he questioned me if he already knew.He said: ‘Will you tell me where the 3rd Division is?’I replied: ‘You will know d—— soon when he hits you. I’ll tell you nothing.’The officer then said, ‘You may go.’

In late 1916, Walter was transferred to Russian Poland where conditions were even worse. He described working in the fields:

‘We went out at five in the morning and got back about midnight. The pay was 3d a day. We were camped in a pig-sty, which was thick with vermin, and the food was so bad that we played up. The result was that we were locked up for three days.’

The winter of 1916 was brutal -

‘It was a cruel winter in Poland in 1916. Many of the Russians collapsed through the extreme cold. We were not allowed to take our overcoats with us when we went out to work. We were all frost-bitten; we all turned blue in the face, and we used to laugh at each other.’

Eventually, he was returned to Dülmen, then transferred between camps doing farm labour. He even planned and attempted an escape -

‘One day I told Matilda (the German woman I was working with) that I wanted to go away for a while. I sneaked away and travelled three days and nights. I had no food with me, and I subsisted on whatever I could get out of the ground — raw potatoes, beet, turnips and the like. I got to within four kilometres of the Holland border. I was eventually espied by children in one of the villages, who cried out in German, ‘A prisoner of war.’ I knew then the game was up.’

He was captured again and punished -

‘I was told that I had rendered myself liable to be shot. The sentence was 21 days in solitary confinement on bread and water. I did five days of the sentence and then went ‘crankum’ — that was, feigned sickness. I always did that when the treatment was pretty bad.’

He later explained the grim rations he endured -

‘Had it not been for the Red Cross parcels we must have starved. If we could have got rats to eat they would have been very welcome. Rats were good, jolly good.’

The guards forced the prisoners to work long hours, especially in summer -

‘The prisoners in the summer worked 18 or 19 hours a day. My cunning always pulled me through. I always went ‘crankum’ when I was overworked.’

His final words about his time as a POW? Simple and poignant.

“I was full of joy when at last he turned his back on Germany and breathed once more in an atmosphere of liberty and freedom.”

Eventually, due to ongoing health issues including damage to his lungs, Walter was assessed by multiple German and Dutch doctors and approved for prisoner exchange. He returned to England in April 1918 and later made it home to Granville:

“My first thoughts were to thank the Almighty for His great love and protection to me. I was twice recommended for exchange to Switzerland and twice for England by different doctors and put down each time by the head doctor of the different camps... Out of the eleven men from my camp ten passed either for one place or the other. I felt very sorry for the poor chaps who had to go back into captivity...

Oh, how happy and excited were the poor chaps to be free once more! And what a splendid reception and welcome we received from the Dutch people. They were in crowds at Venlo, the first station over the border, to meet us. They gave us fine ham sandwich rolls, cups of milk, cigars, cigarettes, chocolates, newspapers and magazines... It was grand to have such a hearty welcome...

We arrived at Rotterdam at 9.30 p.m., where we had another splendid reception... We put up in the Y.M.C.A. building on the wharf and had to stay there five days until the Red Cross convoy ships came in... Just before leaving we were presented with a pale blue envelope containing a packet of cigars, cigarettes and two packets of chocolate with these words printed on the outside: ‘God bless you all. Neutral Holland’s thoughts and heartiest wishes for a safe return to your Mother Country.’

We had a splendid trip across and landed safely at Boston in dear old England... As we stepped on to the wharf the Mayor of the town, in his robes of office, met us and shook us by the hand... Each man was presented with a card bearing a message from the King and Queen of England -

‘The Queen and I send our heartfelt greetings to the prisoners of war of my army on your arrival in England. We have felt keenly for you during your long sufferings, and rejoice that these are ended and that this year brings to you brighter and happier days. — George R.H.’

...Motor cars were waiting to whirl us through the streets of London to King George’s Hospital... Miss Chomley, of our Red Cross, came to see all the Australian boys... Miss Pennyfather, of the Australian Anzac Society... the Duchess of Bedford... I am in fairly good health. I got over on the exchange with my ‘crook’ arm, but it is tip-top.”

— Private Walter A. Potter, letter to his mother, 15 April 1918

Prisoner of War – George

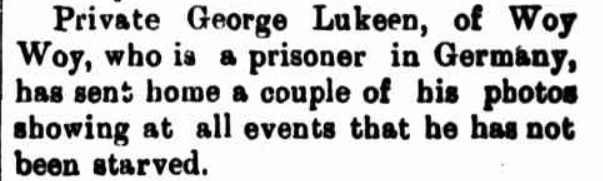

George was reported missing after the Battle of Fromelles and later confirmed to be a prisoner of war in Germany. He was eventually interned at Friedrichsfeld camp, near Wesel. Despite the harsh conditions, George did his best to stay in touch with those at home and reassure them of his wellbeing.

One article in The Gosford Times noted that he had not been starved, prisoners often wrote home saying conditions were good so that it would pass German censors.

In a letter dated 2 March 1917, George wrote from Friedrichsfeld to a family friend, Mr J.W. Browne of Patonga:

“Walter Potter was made prisoner with me, but I have not seen him for some time. I wrote to his people at Granville… I have received one parcel from [the Red Cross], in addition to the usual weekly parcels, but they do not say who they are from, so I suppose it was on your account. The winter has been very bad in Germany, and the cold intense.”

Back Home

After enduring long months of captivity in Germany, Walter was finally repatriated to England in April 1918, and made his way back to Australia that July. His welcome home at Granville was a joyous one, with the family overjoyed to see him safe after the earlier reports had falsely listed him as killed in action. George followed soon after. He had been released from Friedrichsfeld POW camp and arrived home in 1919, returning to Woy Woy and reconnecting with those who had waited anxiously for news. George did have a nasty surprise when he returned.

He owned a small two-roomed cottage situated in what is known here as Horsfield or Andrew's Bay and during his absence some "skunk Huns" smashed open the walls, stole most of the contents, and practically wrecked the place.

That this could be done to someone on service incensed resident H J. Piper and he wrote to the editor of the local paper calling for help :

“My object in writing to you, Sir, is to bring thecase under the notice of the public, with the object of collecting sufficient money to repair the unfortunate soldier's home, and to secure some responsible person who will act as caretaker. This done, I will pay the insurance premium to cover the property against fire risk and keep it paid up till Private Lukeen returns from the war. In conclusion, let me express the hope that the "skunk Huns" above referred to will be speedily brought to justice. — Yours, H J Piper” .

It is not known if the appeal was successful, but it does reflect the degree of support for the soldiers far from home. While relieved to have the War behind them, home was not untouched by tragedy. Just months after their return, the Spanish influenza pandemic swept through the Potter household:

“The pandemic has caused sad trouble in the Potter family, who reside in Good Street, Granville. The son, George, was the first attacked, and other members of the family became infected in quick succession... Mrs. Potter, her son George, and daughter, Mabel Letitia, were removed to the Rookwood State Hospital, and three other daughters and a daughter-in-law were nursed at home. The last-named is wife of Mr. Walter Potter, a returned soldier, who was a prisoner of war in Germany.”

Walter’s sister Mabel Letitia Potter succumbed to the illness while in hospital and was buried at Rookwood. The rest of the family eventually recovered, but the loss left a lasting mark. Walter was officially discharged from the AIF in March 1919. Shortly afterwards, 17 May, he married Dora Evelyn Wilcox and the couple later settled in the Sutherland area of Sydney. Together they had six children:

- Arthur Cheney (1919–1953),

- Mabel Mary (1921–1962),

- Thelma (1922–1924),

- Dora Rae (1925–1987),

- Allan George (1928–1986),

- and Charles Ronald (1929–1998).

Walter worked as a carpenter and remained close to his extended family in Granville. Walter passed away in Sutherland on 22 June 1945, aged 60, and is buried locally in the Sutherland Shire.

George was also repatriated to Australia and formally discharged from the AIF in April 1919. He returned to the Potter household in Granville and continued to be regarded as a beloved adopted son. In 1920, he married Doris Lillian Barnett, and the couple lived locally for several years. George died on 2 October 1929, aged 45, at Prince of Wales Hospital, Randwick. He was buried at Rookwood Church of England Cemetery.

Mates, Brothers, Prisoners

Walter and George were more than just mates in war — they were family in every sense. Raised under the same roof, they trained together, fought together at Fromelles, were captured together, and endured the hardship of German prison camps. Though their paths diverged during captivity, both eventually returned home to Granville and resumed life in the shadow of the war they had survived.

Links to Official Records

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).