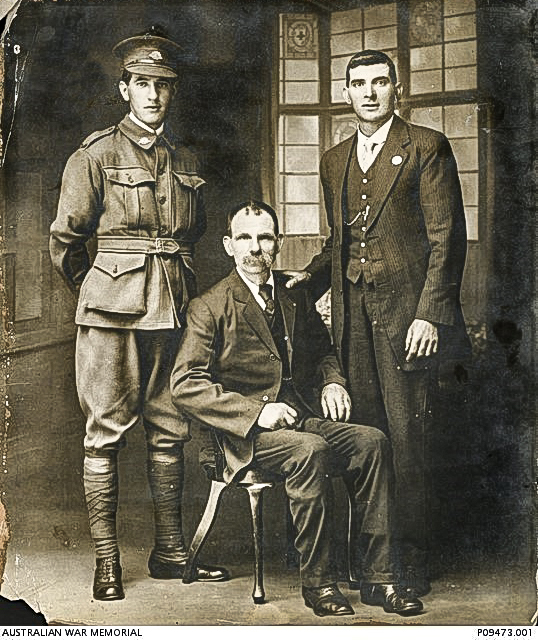

Edward George SMITH

Eyes brown, Hair brown, Complexion brown

Edward Smith – A Mother’s Anguish

Can you help us identify Edward?

Edward was killed in Action at Fromelles. As part of the 54th Battalion he was positioned near where the Germans collected soldiers who were later buried at Pheasant Wood. There is a chance he might be identified, but we need help. We are still searching for suitable family DNA donors.

In 2008 a mass grave was found at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 (Australian) bodies they recovered after the battle.

If you know anything of contacts for Edward here in Australia or his relatives from England and Scotland, please contact the Fromelles Association.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

Early Life

Edward George Smith was born on 1 July 1893 in Lithgow, New South Wales, the eighth of Elizabeth (nee Morgan) and William Smith’s nine children – 4 sons and 5 daughters. Elizabeth had been born in Newcastle NSW; William emigrated to Australia from London in 1871 when he was 16 years old. He and Elizabeth were married just a year after he arrived.

The family lived northwest of Sydney in Orange, Bathurst and Lithgow until at least 1896, after which they moved to the Wollongong coal mining area, living in Fern Hill / Corrimal. William became an official at the Mt Keira colliery, not far from Fern Hill. His 1933 obituary notes that he and his family were held in high regard and that he walked to work – ‘a fair hike for a man of his years’. Edward and his brother David were miners, presumably working at Mt. Kiara.

Off to War - Egypt

Edward and David signed up to go to war, David in March 1916 and Edward in August. Edward was assigned to the 2nd Battalion and began his military training. He had spent three years in St George's Rifles, Citizen Military Forces prior to enlisting, so he would have been used to the military. Compared to many of the recruits at this time, Edward had a long stretch of training in Australia, not leaving Australia until 8 March 1916 on board HMAT A15 Star of England for the month-long trip to Egypt.

With the soldiers returning from Gallipoli and the large number of recruits coming in from back home, major reorganizations of the troops had been underway since early 1916. Soon after Edward arrived he was reassigned to the newly formed 54th Battalion, B Company, who were at Ferry Post guarding the Suez Canal. The 54th then spent all of May at the front line trenches in Katoomba Heights, 8 miles from the Suez Canal.

Fromelles

The call to the Western Front to join with the British Expeditionary Force came on 20 June and the 982 soldiers of the 54th Battalion left Egypt. They sailed on the Caledonian for the 10-day trip to Marseilles via Malta. After disembarking in France there was a three-day train trip to Hazebrouck, 30 km west of Fleurbaix.

By 2 July, the Battalion went Thiennes where they were billeted in barns, stables and private houses for a week. Training now included the use of gas masks and exposure to the effects of artillery shelling. It was hoped that these tests would “inspire the men with great confidence”.

Source AWM4 23/71/6 54th Bn War Diaries July 1916 page 2

On 10 July they moved to Sailly sur la Lys and on the 11th they were into the trenches in Fleurbaix. The health and spirit of the troops was reported as good. After a few days getting exposed to the trenches, they moved back to billets in Bac-St-Maur. Major Roy Harrison wrote home on July 15th. With his Gallipoli experience, the tone in this letter was certainly circumspect for the upcoming battle.

“The men don’t know yet what is before them, but some suspect that there is something in the wind. It is a most pitiful thing to see them all, going about, happy and ignorant of the fact, that a matter of hours will see many of them dead; but as the French say ‘C’est la guerre’.”

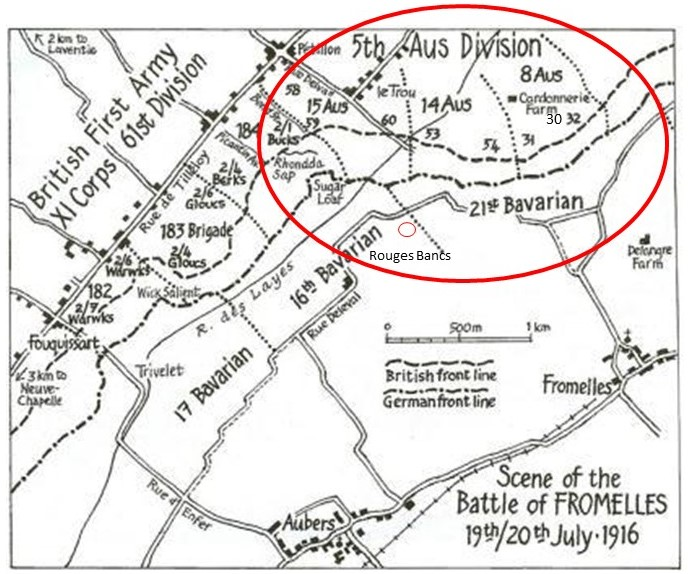

An attack was planned on the 17th, but it was delayed due to the weather. The weather soon improved and by 2.00 PM on 19 July the 54th were in back in the trenches, ready for the Germans. The main objective for the 54th was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the 54th and the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfiladed fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction.

As they advanced, they were to link up with the 31st and 53rd Battalions to protect their flanks. The attack began at 5.50 PM. They moved forward in four waves– A Company and Edward’s B Company were the first two waves and C and D Companies were the third and fourth. The first waves did not immediately charge the German lines, they went out into No-Man’s-Land and lay down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift.

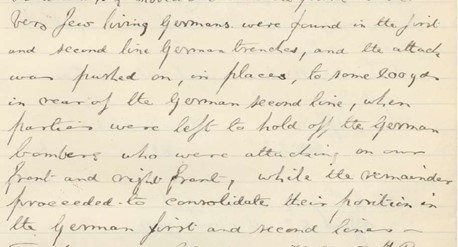

At 6.00 PM, the German lines were rushed. The 54th were under heavy artillery and machine gun and rifle fire, but were able to advance rapidly. The 14th Brigade War Diary notes that the artillery had been successful and “very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches”.

Some of the advanced trenches were just water filled ditches which needed to be fortified to be able to hold their advanced position against future attacks. The 54th were able to advance and link up with the 53rd and the 31st and 32nd, establishing a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm. However, the 60th on their far right had been unable to advance due to the devastation from the machine gun emplacement at the Sugar Loaf, leaving this flank exposed.

They held their lines through the night. However, with heavy losses and the German counterattacks, the Australians were eventually forced to retreat. This was complicated by the fact that the right flank had become exposed and which allowed the Germans access to the first line trench BEHIND the 54th/53rd and the German advances in the trench had to be repelled as the Australians retreated.

By 7.30 AM on the 20th the 54th were pulled all the way back to Bac-St-Maur, 5 km from the front. In this very short period of time, of the 982 soldiers of the 54th that left Egypt, initial roll call counts were - 73 killed, 288 wounded and 173 missing. Ultimately, 173 soldiers from the 54th were killed in action or died from their wounds. Of this, 102 were missing, including Edward.

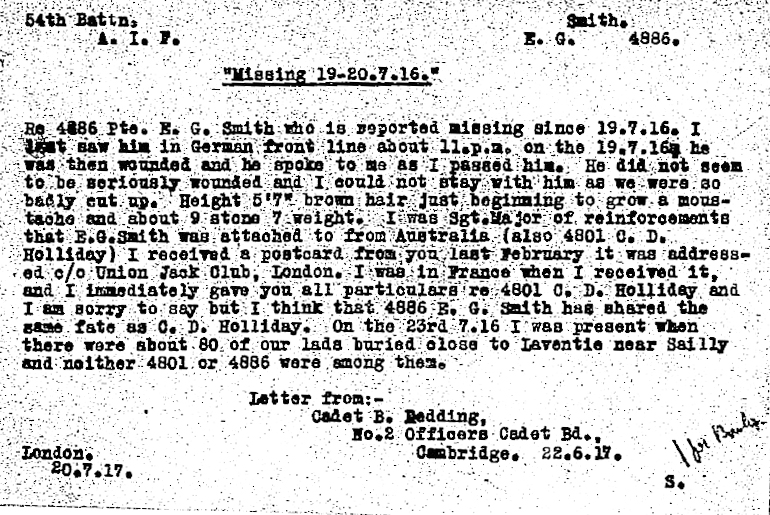

From a July 1917 Red Cross witness statement, Sergeant Major B. Redding reported that Edward was wounded at around 11 PM in the advanced area of the charge. He did speak with Edward and said that he did not seem to be seriously wounded, but Redding needed to move on. In his statement, Redding then went on to guess that Edward did not make it off of the battlefield. Private G.S. Hickey (4797), also of B Company, states Edward was killed, but then refers to contact B. Redding for details.

No other reports of what happened to Edward are available.

All we know for sure is that Edward was in the advanced area of the attack and was not at roll call – Missing in Action.

A Mother’s Multi-Year Quest for Closure

Confirming Edward’s fate would have been particularly hard on Elizabeth as all four of Elizabeth Smith’s sons would be gone by the end of 1916. Two had died at younger ages, David had died in November 1916 due to pneumonia/tuberculosis which was diagnosed shortly after he had enlisted and Edward was ‘missing’ since the July battle.

Certain anguish for a mother. Her personal search for closure went through three stages over three years:

- the period of post-battle uncertainty of being missing

- ‘news’ in 1917 that Edward had been wounded and was a POW (received after he had been formally declared as killed in action),

- the potential that his mates had buried him.

1. MISSING?

Following the battle, the Army undertook extensive efforts to track down individual soldier details but given the scale of the battle outcome it was not a fast process. After a month went by, Elizabeth contacted the Army for news but there was nothing yet they could offer.

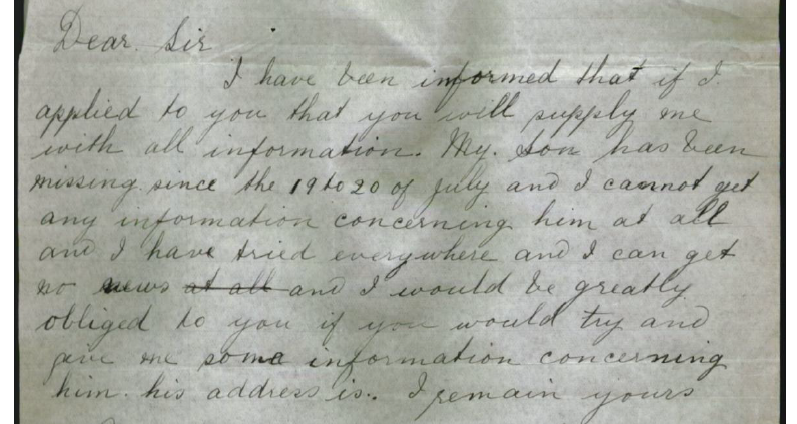

In early October 1916 , Jean Hunter, who was the same age as Edward and was from the neighbouring town of Woonoma, NSW, also wrote the Army seeking information about Edward, ‘a friend of mine whom I am very interested in’. Elizabeth next wrote to the Army in late October, but now in a much more pleading manner - ‘…I have tried everywhere and I can get no news…’.

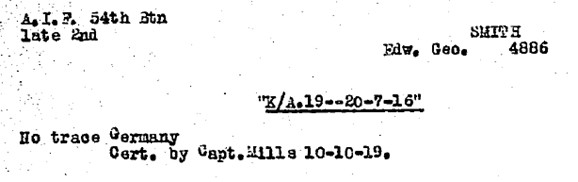

No further correspondence is documented until 4 August 1917 when Edward was formally declared as having been Killed in Action by an Inquiry in the Field.

After the Inquiry, Elizabeth wrote in frustration that:

“ if the Red Cross can give details to her, then why can’t the Army?”

2. A Prisoner of War?

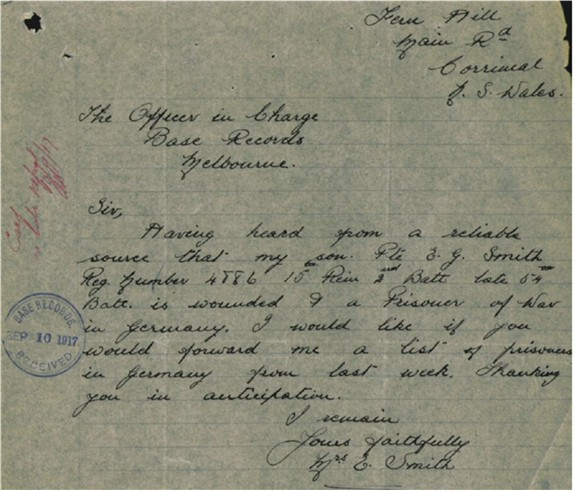

Shortly after the August 1917 Inquiry, Elizabeth’s received some information from a ‘reliable source’ that Edward had been wounded and was a POW.

No details about this are in his file. Edward was never recorded as a POW and was not found from later searches in Germany by the Army.

3. BURIED?

With Edward’s death seemingly confirmed, Elizabeth was still seeking closure by just having Edward’s belongings returned to her. During this time a new possibility of Edward’s fate emerged – had he been buried by his mates?

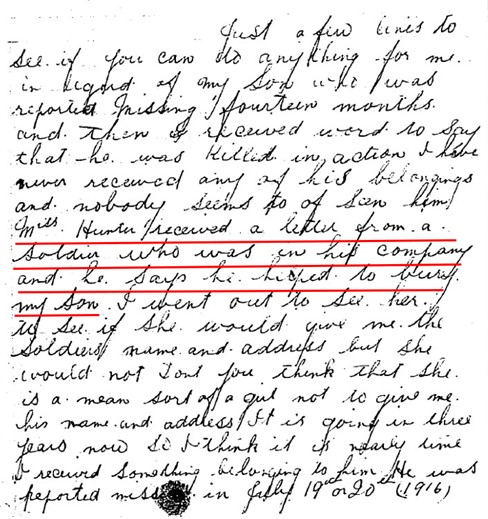

Somehow Elizabeth had heard that Edward’s friend Jean Hunter had received a letter from a soldier in Edward’s company that advised that he had helped to bury Edward.

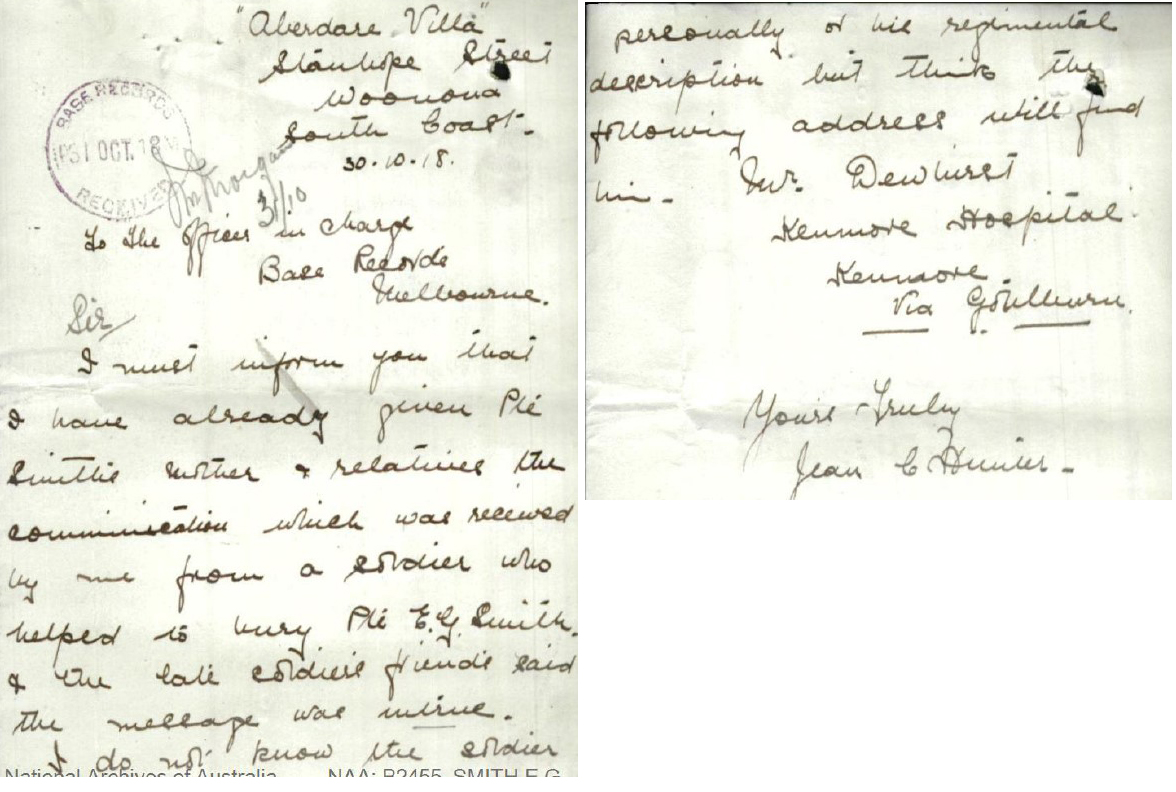

Elizabeth met with Jean around late-September 1918, but when Elizabeth wrote the Army she said that Jean would not pass on the soldier’s contact details. Contrary to this, Jean had also written to the Army in October and said that she HAD passed the information to Elizabeth. However, this letter also said that the advice about Edward being buried was untrue:

“I must inform you that I have already given Pte Smith’s mother & relatives the communication which was received by me from a soldier who helped to bury Pt E.G. Smith and the late soldier’s friends said the message was untrue.

I do not know the soldier personally (sic Dewhurst) or his regimental description, but think the following address will find him. Mr Dewhurst, Kenmore Hospital, Kenmore via Goulburn” (note - J.W. Dewhurst (4476) 54th Battalion, discharged due to disability, Nov 1917)

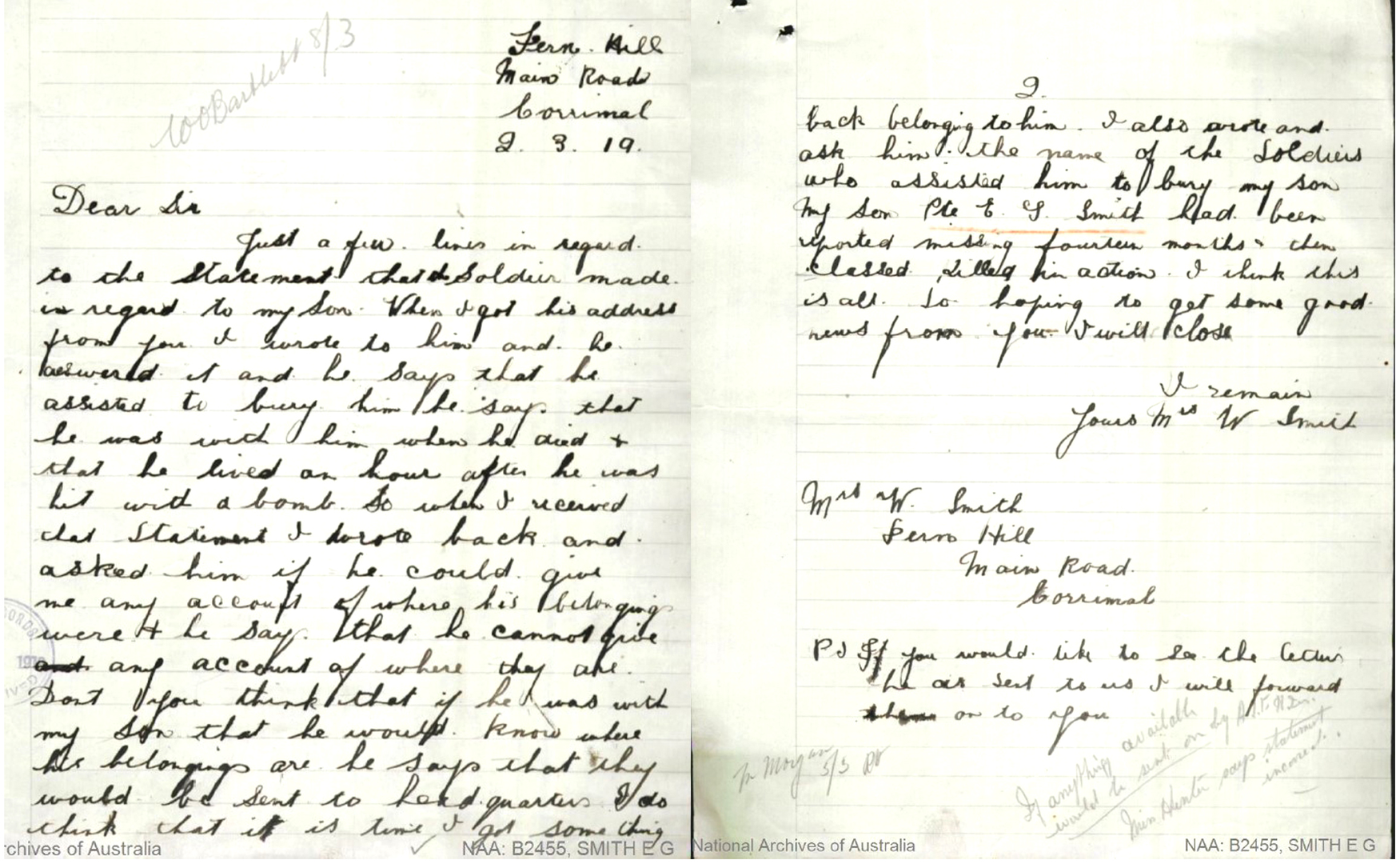

Elizabeth asked the Red Cross and the Army to investigate, which they did. By March 1919, it appears that Elizabeth had been able to contact a soldier (she did not state who it was). In her letter, she states the soldier said:

“…he says he assisted to bury him he say he was with him when he died and that he lived an hour after he was hit with a bomb.”

Regarding where Edward might have been buried, “…he cannot give any account of where they were.”

Elizabeth also asked what might have happened to his belongings and the soldier indicated they would have been sent to headquarters.

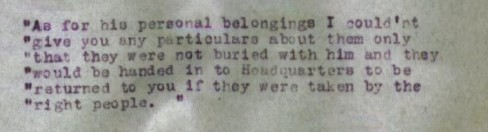

The only soldier’s name that is documented in this string of communications is from Jean Hunter’s letter - J.W. Dewhurst - and the Army did contact him. It is not known exactly what the Army asked in their letter to Dewhurst, but his reply was only that Edward’s belongings were not buried with him.

There was nothing in his reply about Edward actually having been buried by Dewhurst or who might have helped. This lack of clarity seems to be an odd omission if Dewhurst did bury Edward (possibly it was just a ‘battlefield burial’?)

The last of the documented communications is a 13 October 1919 letter from Elizabeth once again asking if they had forgotten about the letter she had written “some time ago” - no response is in the files. Neither Edward’s grave nor his belongings were found. The closure the Elizabeth was seeking was not possible.

Edward was awarded the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll. He is commemorated at the V.C. Corner (Panel No 11), Australian Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles, France and with his parents.

Still Potential for Closure?

In 2008 a mass grave was found at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 bodies they recovered after the battle. Through DNA matching from family donors, as of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified, including 28 of the 102 originally unidentified 54th soldiers.

The identified soldiers are now properly buried at the Pheasant Wood Cemetery. The grave was in the vicinity where Edward was fighting. However, Edward’s ID tags were not reported as having been recovered by the Germans nor was he on a German ‘Death List’. Edward still could be among the remaining unidentified soldiers, however.

We need to find family DNA donors to confirm this. Please contact the Fromelles Association if you know of any connections to Edward’s family here in Australia or in the UK.

Family connections are sought for the following soldier

| Soldier | Edward George Smith (1893-1916) |

| Parents | William Smith (1855 - 1933) b Einfield Middlesex England, d Fernhill NSW and Elizabeth Morgan (1857 – 1944) b Newcastle NSW, d Fernhill NSW) |

| Siblings | William John (1875 – 1878) b Orange NSW | ||

| William Edwin (1877 - 1905) b Orange NSW, d Bandon Grove NSW, m Ada Alize Getty Neilson | |||

| David Henry (1878 - 1916) b Orange NSW, d Wollongong NSW, m Jane Curran | |||

| Florence Emma (1880- 1951) b Bathurst NSW, d Paddington NSW, m Alfred Mahoney | |||

| Maud Alice (1882 – 1962) b Lithgow NSW, d South Hurstville NSW, m John William Stevens | |||

| Amy W (1884 - 1962) d NSW Hurstville, m Jack Geary | |||

| Mary Ann (1887 – aft 1905) b Lithgow NSW, d NSW | |||

| Leela Margaret Maria (1896 – 1952), b Lithgow NSW, d Corrimal NSW) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Charles Smith (1824 - ) b Little Chelsea Middlesex England and Sarah (1826 - ) b Stoke Buckinghamshire England) | ||

| Maternal | William Morgan (1831 - 1894) b Camarthen Glamorganshire Wales d Lithgow NSW and Catherine Cameron (1838 – 1866) b Keppock Isle of Skye Scotland d Nundle NSW |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).