William Christopher BRUMBY

Eyes blue, Hair brown, Complexion fresh

‘Lost Boys’ from Sorrento – Bill Brumby and Bert Hibbert

We are grateful to Peter Munro for his example of dedication, Clive Smith and the Nepean Historical Society and to the Mornington Peninsula News.

William is identified at Pheasant Wood.

After 108 years, Bill Brumby is no longer ‘lost’. DNA matching from family members has been successful in identifying him as having been originally buried in the Pheasant Wood grave dug that had been dug by the Germans. The 2024 identifications announced on 23 April 2024 bring the total identifications of the 250 soldiers in the burial site to 180.

Bert Hibbert remains unidentified.

Early Life

William (Bill) Christopher Brumby was born in April 1887 at Conisholme, Lincolnshire, England to William and Eliza (nee Marshall) Brumby. He had an older sister, Eliza, who was born in 1884. William and Eliza had married on 28th January 1884 at St Mary, Binbrook, Lincolnshire. William was a farm worker and worked as a farmer and an Agricultural Foreman. Young Bill attended the Church of England school in Kelstern, Linconshire and followed his father’s footsteps and became a farmer as well.

Bill’s father died in 1908, after which he went to work and live with his sister and her husband at ‘Hedge Ends Farm’ Grimoldby, Lincolnshire. It is also likely he began to support his mother at this time.

Bill’s mother did remarry, to Alfred Rowle in 1915. This relationship this may have relieved Bill from supporting his mother and given him the chance to travel. Bill left for opportunities in Australia on 8 May 1914 on the Orient Line’s Osterly. He settled in Sorrento, Victoria and, while having only been there a short while, was described in the ‘Peninsula Post’ as

“Of a quiet and retiring disposition, his genial manner made him a host of friends in Sorrento.”

Off to War

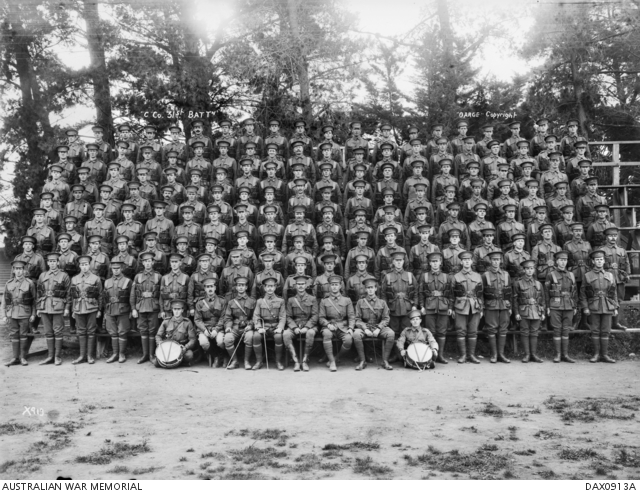

When recruiting for the War began in Australia in earnest, Bill enlisted with the Australian Imperial Force on 12 July 1915. He was assigned to the newly formed 31st Battalion, C Company along with his Sorrento friends Bert Hibbert (706) and Ernie White (753). The battalion was to have two companies from Queensland and two companies from Victoria. The Victorians trained at the Broadmeadows camp and the Queenslanders joined them in early October to complete the battalion.

Before sailing to Egypt from Melbourne on 9 November aboard the troopship Wandilla, the 991 soldiers of the 31st had been on parade in Melbourne in front of a good crowd. The Minister for Defence, H.F. Pearce, said, “I do not think I have ever seen a finer body of men.”

Source INFANTRY MARCH PAST (1915, November 6). Weekly Times (Melbourne, Vic. : 1869 - 1954), p. 32. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article132708935

The Wandilla docked at Port Suez exactly four weeks after leaving Melbourne. They were first sent to Serapeum to continue their training and to guard the Suez Canal. Near the end of February they moved to the large camp at Tel el Kebir. The 60 km trip must have been unpleasant, as it was reported that they were moved in ‘dirty horse trucks’.

Source AWM4 23/48/7, 31st Battalion War Diaries, Feb 1916, page 5

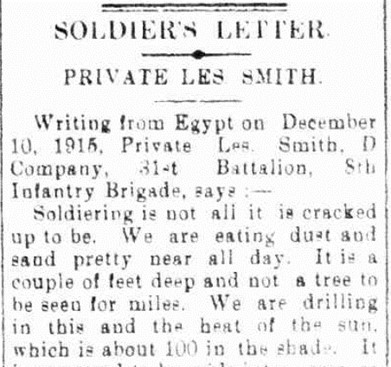

The next move was at the end of March, back to the Suez Canal at the Ferry Post and Duntroon Camps and then finally to Moascar at the end of May. The months passed in training and sightseeing, but by the time the 31st Battalion was transferred to France, the men were all heartily sick of Egypt. Private Les Smith’s (934) letter home pretty well sums it up.

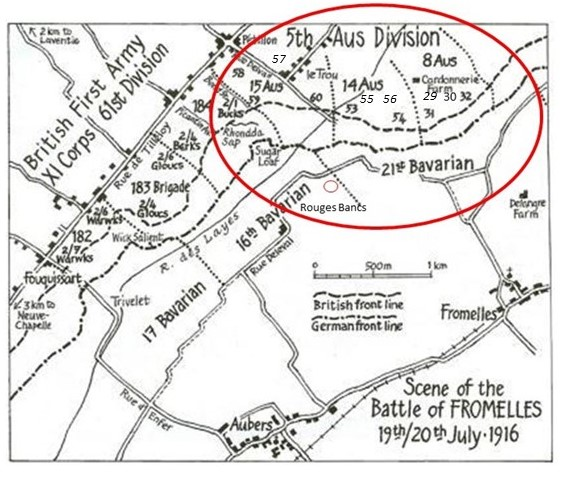

On 15 June, the 31st Battalion began to make their way to the Western Front, first by train from Moascar to Alexandria and then aboard the troopship Hororata, sailing to Marseilles. They disembarked on 23 June, boarded trains to Steenbeque, then marched to the camp at Morbecque, 35 km from Fleurbaix, arriving on 26 June. The battalion strength was 1019 soldiers. Training continued, now with how to handle poisonous gas included in their regiment.

They began their move towards Fleurbaix on 8 July and by 11 July they were into the trenches for the first time, in relief of the 15th Battalion.

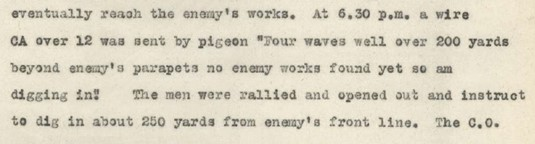

The original attack was planned for the 17th, but bad weather caused it to be postponed. On the 19th they were back into the trenches and in position at 4.00 PM. “Just prior to launching the attack, the enemy bombardment was hellish, and it seemed as if they knew accurately the time set.”

Source AWM4 23/48/12, 31st Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 23

The assault began at 5.58 PM and they went forward in four waves - Bill’s C Company and A Company were in the first two waves and B and D Companies in the 3rd and 4th waves. The pre battle bombardment did have a big impact and by 6.30 PM the Aussies were in control of the German’s 1st line system, which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

Source AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

Unfortunately, with the success of their attack, ‘friendly’ artillery fire caused a large number of casualties. By 8.30 PM the Australians’ left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return artillery support was provided and the 32nd, who also had the job of holding the flank to the left of the 31st, were told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line, but they were low on grenades, there was machine gun fire from behind from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides.

At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank. Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, portions of their rear trench had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers. At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left themselves, the only resistance the 31st could offer was with rifles.

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled a shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

Source AWM4 23/48/12, 31st Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 29

The 31st were out of the trenches by the end of the day on the 20th. From the 1019 soldiers who left Egypt, the initial impact was assessed as 77 soldiers were killed or died from wounds, 414 were wounded and 85 were missing. The bravery of the soldiers of the 31st was well recognised by their own Battalion commanders.

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large amount of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The ultimate total was that 161 soldiers were either killed or died from wounds and of this total 82 were missing/unidentified.

After the Battle

Bill and his friend from Sorrento Bert Hibbert were killed during the battle, but there are no records of what happened to them. They remain unidentified to this time.

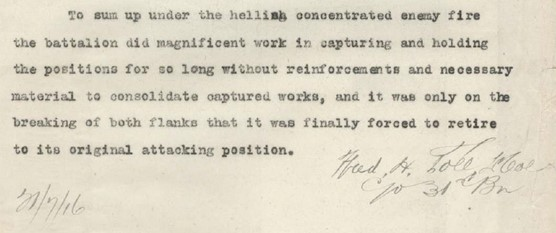

Their friend Ernie White did survive, but he received a gunshot wound to his face during the battle. He rejoined the unit a month later. He was discharged for family reasons in February 1917 and returned to Australia. Bill’s sister was not advised of what happened to him (there are no records of his mother being notified either), so she wrote seeking information about him in November 1916. Bill had been writing his sister regularly, but those letters had stopped. Eliza’s letter came to the Army via the Victorian YMCA.

(Note - the 29 Sept date cited in Eliza’s letter was likely when Bill’s last letter was posted – long after the battle).

The Army’s reply in January 1916 advised that they had no information on Bill and ‘it may be assumed he is with his unit.’ They also stated that any communications about his status would be via his mother, the designated next of kin. There are no further communications in Bill’s records.

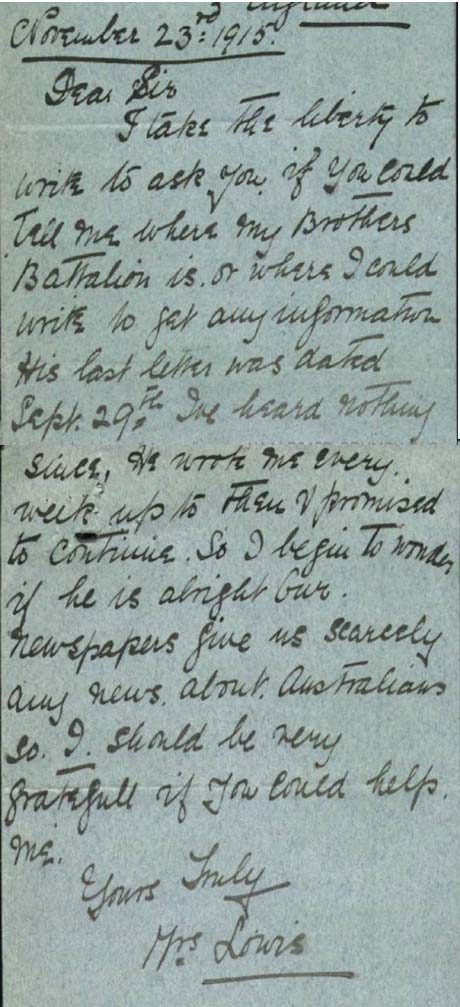

There are no records of Bill’s body being recovered by the Australians or by the Germans. The report on his death states he was Killed in Action, BUT it mistakenly states he died on 21 July 1916…after the battle. While Bill’s body was not recovered, he does have a note in his on AIF file.

There are similar notes in Bert Hibbert’s as well other missing soldiers’ from the 31st including 719 Reginald Alexander Bean, 589 Bertram Bloomfield, and 829 Leslie Charles Brown. Alongside William, all were commemorated at Villers-Bretonneux and had an original death date of 21st July 1916. All remain missing with no known grave.

‘Lost Boys’ from Sorrento

In June 2014, amateur historian Peter Munro visited the Western Front with details of burial and commemorative locations of the 13 Sorrento lads who had been killed in action.

However, he and his French battlefield guide could not find the names of Hibbert and Brumby on the commemorative wall at Villers-Bretonneux, as stated in documents from the Australian War Memorial, Canberra. Mr Munro and his guide initially thought the names must have been removed from the Villers-Bretonneux memorial wall and inscribed on the Australian Memorial wall at VC Corner, Fromelles, more than 100 kilometres away.

But, arriving there two hours later, they looked for the Brumby and Hibbert names in vain. So, not only were their bodies never recovered, their names are also not commemorated with their other unidentified mates from the battle at either site. It turns out that only those soldiers whose date of death was listed as 19 or 20 July were initially placed of the wall at VC Corner.

Brumby and Hibbert were mistakenly reported as “missing presumed dead” on 21 July and so were overlooked. The Australian War Memorial and Commonwealth War Graves Commission in the UK was notified and, after an email trail over four months – including letters to MPs and government ministers, the names of Hibbert and Brumby were belatedly included on the commemorative wall at Fromelles where both had died in battle. In mid-August 2014, Mr Munro received an email from the Office of Australian War Graves stating that the Commonwealth War Graves Commission would add the boys’ names, along with three others who perished at Fromelles, to an extra wall panel and that war records would be updated. In April 1915, Mr Munro was told work had begun on inscriptions.

In September he revisited the cemetery at VC Corner to place a wreath of red poppies and an Australian flag from the Sorrento and Portsea RSL near the names. The two Sorrento ‘Cobbers in Arms’ are now properly commemorated due to having been ‘found’ thanks to Peter Munro’s dedication.

Bill is also commemorated at a memorial in the grounds of St Edith's Church, Grimoldby, Linconshire and Sorrento Victoria.

'Aussie' Bill

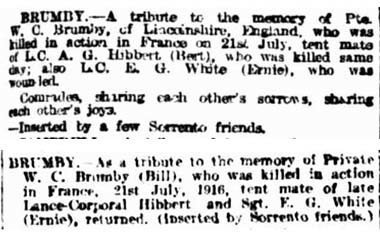

Bill had clearly settled into Australia in his short time here. Clive Smith, of the Nepean Historical Society, said ‘I had surmised that William may have lived with the Whites at Sorrento, but have no firm evidence of this.’ He was missed by his Australian friends, with memorial notices posted immediately after his death and a year later.

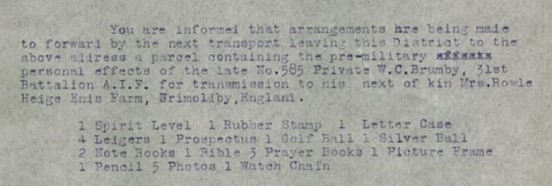

The support from his friends went further than just memorial notices. After Bill had been killed, Ernie White’s mother pursued the Army to see if Bill’s personal effects that she had been looking after could be arranged to be sent to his family in the UK. The Army agreed, so Bill’s family were at least able to get some closure.

Bill is found at last, identified in 2024.

After the battle, German soldiers removed 250 Australian casualties from the battlefield, burying them in a large pit near Pheasant Wood. This mass grave was not discovered until 2008.

Identification by DNA matching has been ongoing since that discovery as relatives have been able to found. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers in the grave have been identified, including 23 of the 82 originally unidentified soldiers from the 31st.

Bill’s family was traced to Linconshire and Yorkshire, England and they collaborated on his headstone inscription. These words very much reflect the sentiment of Bill’s time.

WHEN O’ER THE SEA

WENT HONOUR’S CRY

HE CAME TO HELP

TO FIGHT TO DIE

Lest we forget.

After the battle, German soldiers removed 250 Australian casualties from battlefield, burying them in large pits near Pheasant Wood. This mass grave was not discovered until 2008. As of 2024, 180 of the 250 soldiers in the grave have been able to be identified by DNA matching from family members.

Pheasant Wood Military Cemetery

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).