Chester Cecil CHURCH

Eyes grey, Hair light, Complexion fair

Chester Church - From a Jersey Seaman to the Australian Infantry

The Church Family - England, Jersey and Australia

Unlike many of the young Australians who enlisted in WW1, the Church brothers, Chester and Theo, were very well travelled. Their parents Mark and Susannah Louisa Church (nee Flowers) came from the south of England. They had married in 1882 at St. Mary Lambeth, London, but migrated to Australia, settling in Brisbane. Mark had been a draper’s assistant and later became a hairdresser. Susannah’s eldest sister, Rosina Wilkinson, and her family were also in Brisbane, having arrived in 1885.

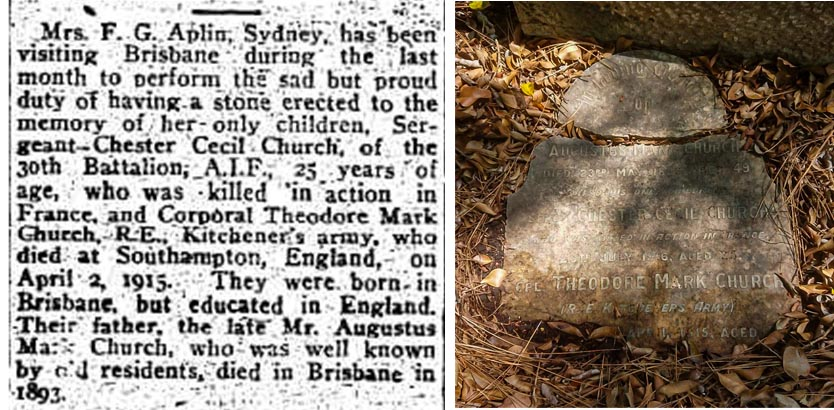

Theodore (Theo) Mark was born in in Brisbane in 1886 and Chester Cecil in 1891. When Chester was born they were living in Chester St, Teneriffe, Brisbane. Unfortunately, their father Mark died when Chester was only two and Theo seven. Susannah remarried two years later in Sydney to Frederick George Aplin and the boys took the name Aplin. In 1897 Fred had become an alderman and auditor for the east ward of Five Dock.

Susannah’s sister Rosina and her family had also moved to Sydney. While seemingly well settled in Sydney, the Aplins returned to England. Per the 1901 census, they were living at 23 Disraeli St, Putney and Fred was working as an agent for precious stones.

Chester attended Victoria College in Jersey in the early 1900’s for 3-4 years. His mother said on his Roll of Honour form that he had been awarded a Life Saving medal while there.

As with many public and independent schools, Victoria College had a flourishing Officer Training Corps. With that influence and his brother already serving in the British Army, when Chester was in his late teens he served in the Royal Militia Isle of Jersey. The RMIJ is one of the oldest sub-units of the British Army.

By 1910, 19-year-old Chester had become a seaman, travelling from London to Sydney, on the Norseman. He worked for the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand and within his first two years he had progressed to being a first-grade steward. His enlistment form and input from his mother lists his occupation as a hairdresser, like his birth father, which may have been one of his duties. He was also a member of the YMCA in Sydney.

In 1911, Fred and Susannah had been living in Portswood, Hampshire, but in 1912, at 56 years old, Susannah returned to Australia, alone. Chester was her sole source of support. Chester’s brother Theo began his service in the British Army in 1904 and became a “Wireless Instructor in Kitchener's Army” in the Royal Engineers Signals unit.

He was in Chaubattia, India when the War broke out and his unit was returned to England in December 1914. However, in April 1915 he died of heart disease.

Source: https://wartimememoriesproject.com/greatwar/allied/battalion.php?pid=6127

Off to War

Chester’s last trip as a seaman ended in January 1915, when he returned to Sydney from Vancouver … very well-travelled. With Australia rallying in support of England, War ‘fever’ was on and Chester enlisted on 2 July 1915 at Liverpool, New South Wales. He was assigned to the newly formed 30th Battalion, C Company.

While initially taken on as a Private, given his Royal Militia experience and being 25 years old and 6 foot tall in his boots, he would have attracted attention as a military leader. By 1 October he had been promoted from Private to Corporal to Lance Sergeant. Training for the 30th had commenced in the Liverpool camp, but in September they moved to the Royal Agricultural Show Grounds in Moore Park, Sydney.

There were numerous reports of their activities in the papers:

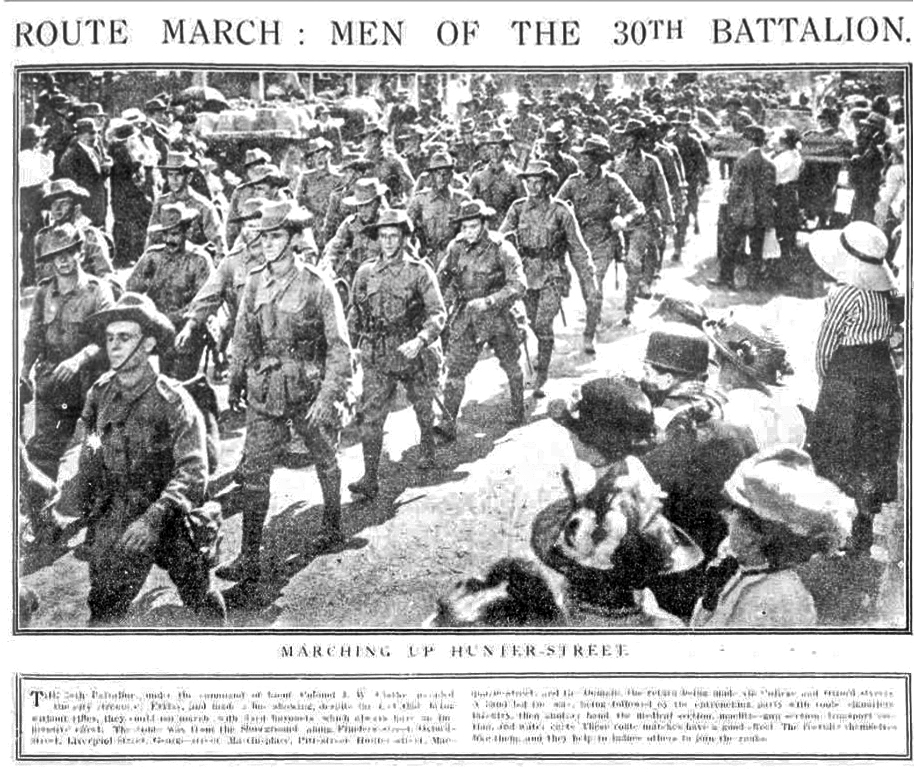

“The 30th Battalion marching up Hunter Street, Sydney on 22 October 1915 “made a fine showing, despite the fact that, being without rifles, they could not march with fixed bayonets, which always has an impressive effect……..A band led the way, being followed by the entrenching party with tools, signalers, infantry, then another band, the medical section, machine-gun section, transport section and water carts. These route marches have a good effect. The recruits themselves like them, and they help to induce others to join the ranks.”

The Battalion left Sydney for Egypt aboard HMAT A72 Beltana at 3.30 PM on 9 November 1915. Their trip was uneventful and they disembarked in Egypt on 11 December. Their first seven weeks were spent at Ferry Post guarding the Suez Canal and continuing their training. February and March were at the camp at Tel el Kebir, where they were inspected by H.R.H. Prince of Wales.

Chester must have continued to show leadership skills and he was promoted to a full Sergeant on 1 April 1916. For much of April and May were back in Ferry Post, including some time in the front-line trenches there. There were the usual complaints of the heat, water supplies and flies.

To the Western Front and Fromelles

The Battalion left Egypt for the Western Front on 16 June 1916 on HMAT Hororata and arrived in Marseilles on 23 June. After landing, there was a 60+ hour train ride to Hazebrouck, 30 km from Fleurbaix. They arrived on 29 June and were then encamped in Morbecque. Private F.R. Sharp (2134) wrote home:

“From the time we left Marseilles until we reached our destination was nothing but one long stretch of farms and the scenery was magnificent.” “France is a country worth fighting for.”

Training now included the use of gas masks and they also would have heard the heavy artillery from the front lines. On 8 July, they were headed to the front lines, first to Estaires, a trip of 20 km, and the next day 11 km to Erquinghem, where they were billeted at Jesus Farm. They got their first ‘taste’ of being in the trenches at 9.00 PM on 10 July.

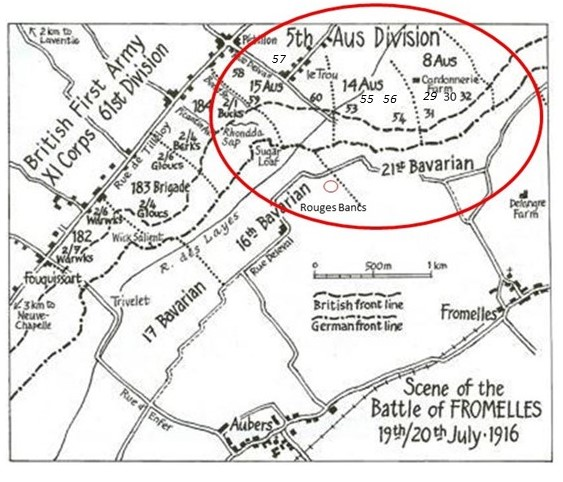

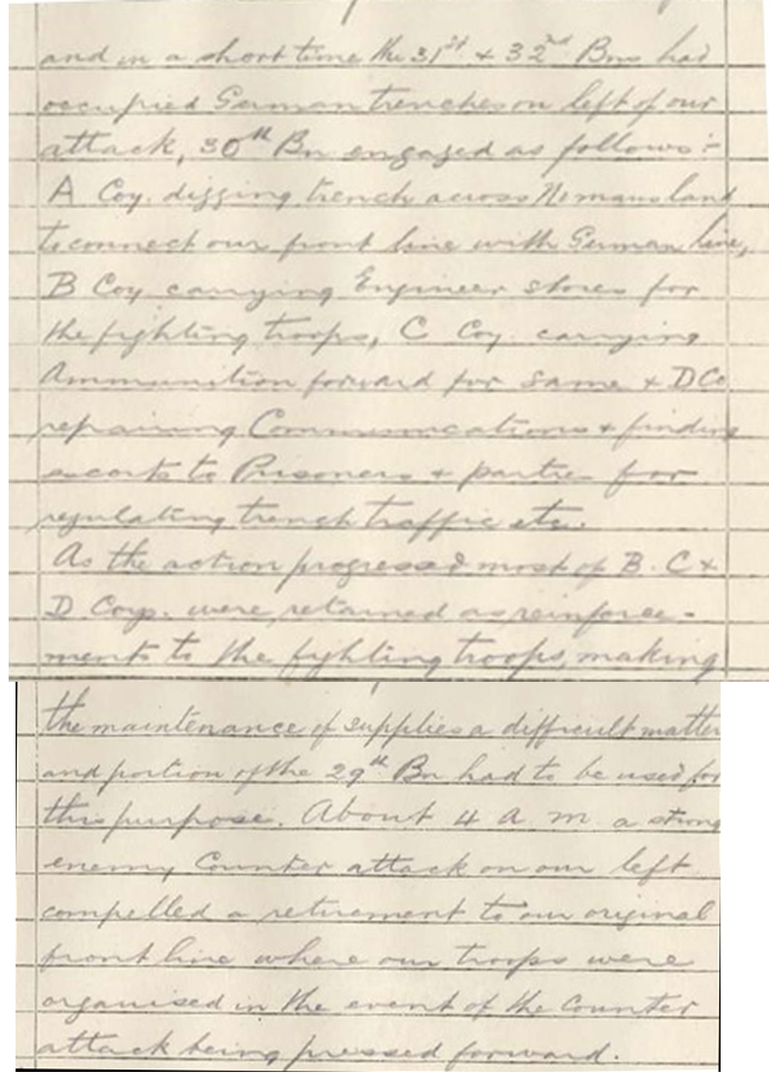

A week later, they got orders for an attack, but it was postponed due to the weather. Then, on 19 July, the 29 officers and 927 other ranks of the 30th Battalion were into battle. The 30th Battalion’s role in the battle was to provide support for the attacking 31st and 32nd Battalions by digging trenches and providing carrying parties for supplies and ammunition. They would be called in as reserves if needed for the fighting.

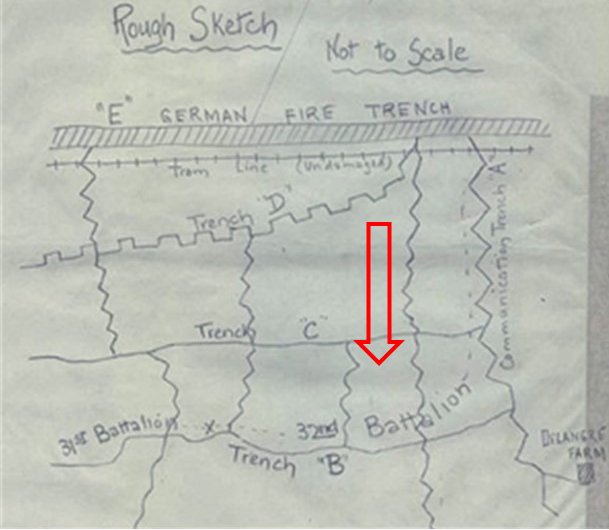

The 32nd’s charge over the parapet began at 5.53 PM and the 31st’s at 5.58 PM. There were machine guns emplacements to their left and directly ahead at Delrangre Farm and there was heavy artillery fire in No-Man’s-Land. The initial assaults were successful and by 6.30 PM the Aussies were in control of the German’s 1st line system (Trench B in the diagram below), which was described as:

“practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

While their role was to be in support, commanders on scene made the decision to use the 30th as much-needed fighting reinforcements. A necessary act, but it had consequences as it interfered with the planned flow of supplies. Chester’s C Company was now fully engaged in the battle.

By 8.30 PM the Australians’ left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and the 32nd Battalion was told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

When the 30th was formally called to provide fighting support at 10.10 pm, Lieutenant-Colonel Clark of the 30th reported:

“All my men who have gone forward with ammunition have not returned. I have not even one section left.”

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine gun fire from behind from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides.

At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map). Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, portions of the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers.

At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance the 31st could offer was with rifles:

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

By 10.00 AM on the 20th, the Germans had repelled the Australian attack and the 30th Battalion were pulled out of the trenches. The nature of this battle was summed up by Private Jim Cleworth (784) from the 29th:

"The novelty of being a soldier wore off in about five seconds, it was like a bloody butcher's shop".

Initial figures of the impact of the battle on the 30th, who were supposed to be in a support role, were 54 killed, 230 wounded and 68 missing. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large amount of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield.

The ultimate total was that 125 soldiers of the 30th Battalion were either killed or died from wounds and of this total 80 were missing/unidentified.

Chester’s Fate

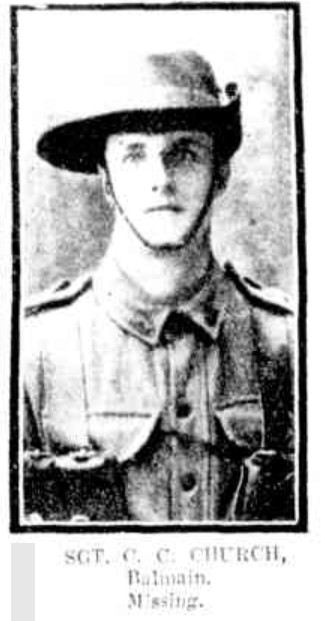

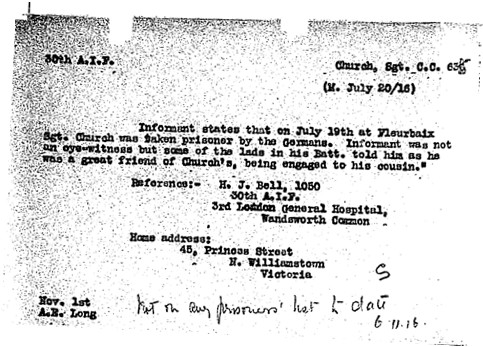

The many witness reports on Chester’s fate vary significantly – taken prisoner or killed.

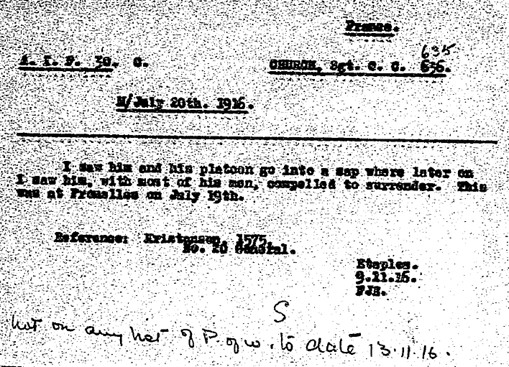

Peter J Krestensen (1575) reported:

'I saw him and his platoon go into a sap where later on I saw him, with most of his men, compelled to surrender. This was at Fromelles on July 19th.'

The handwritten note says he was not on a POW list, however.

While another report was second-hand (below), it came from H. J. Bell (1050) “a great friend of Church’s, being engaged to his cousin”.

Other statements seemed clear that he had been killed.

Sydney W. Strike (289):

'I saw him killed by shell fire just outside his trench at Fleurbaix Fromelles.'

Cyril G. Lavender (1305):

'Sergeant W. Fox, C. Co, 30th Battalion, saw him dead at Fromelles on the 20th July 1916.'

Alfred Walker (8):

‘Church was killed by shell, but could not be brought in’

The truth emerged later with confirmation from the Red Cross that Chester appeared in a German Death List dated 4 November. He was not on any Prisoner of War lists, so the Germans had recovered his body and returned his ID tag:

“no particulars were afforded except that Soldier was deceased”.

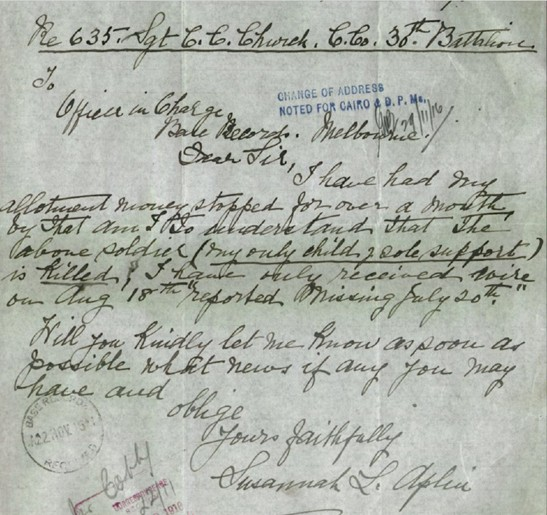

Susannah

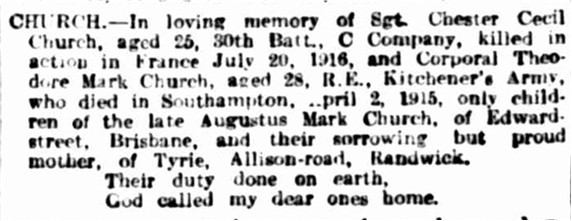

Like many mothers, losing both of her sons (her only children) in 1915 and 1916 would have been extreme and it affected Susanna’s health. Luckily, she seems to have remained close to her sister Rosina and family. Her sons were clearly missed.

A memorial to both of her sons was erected in Brisbane in 1918, but unfortunately it has become derelict.

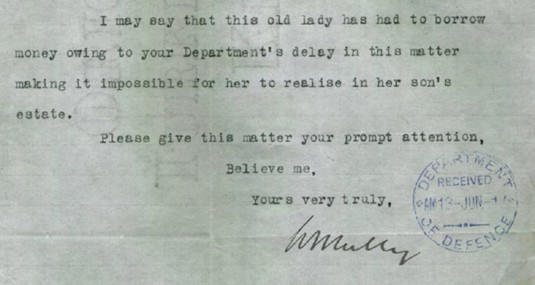

With Susannah having left her husband Frank in the UK in 1912, Chester had been her only source of financial support. When the Army put his pay on ‘hold’ before a death certificate could be issued for the settlement of his estate (as was normal practice), it forced her to go into debt. While there was an ongoing dialogue to settle this as quickly as possible, ‘encouragement’ to speed the process was CLEARLY communicated to the Army.

This was finally settled, but it took a year after Chester’s death. Susanna passed away in 1926, 70 years old. Fred had never moved back to Australia. Chester was awarded the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Scroll and a Memorial Plaque.

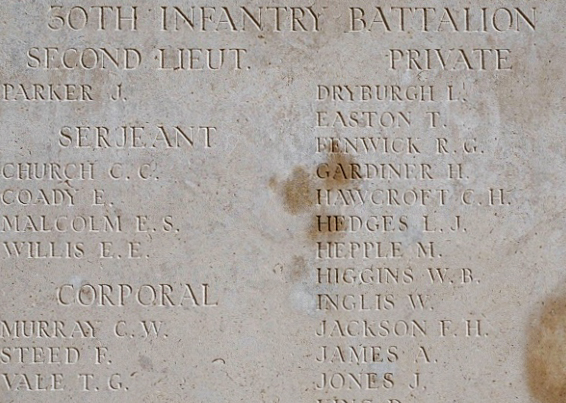

He is commemorated at VC Corner Cemetery and Memorial, Fromelles, France, Panel 2, and the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, Panel 116.

Can Chester be found?

As above, Chester’s body was recovered by the Germans, but there are no details about his burial. They did dig a mass grave at Pheasant Wood that contained the bodies of 250 soldiers. This was discovered in 2008. DNA testing from family members to identify the bodies in the grave has been ongoing and 173 of these soldiers have been able to be identified. DNA donors for Chester have been found, but there was no match for Chester as being in the grave.

Known only to God.

Finding Chester

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Chester Cecil Church (1891–1916) |

| Parents | Augustus Mark Church (1844–1893, Compton Martin, Somerset, England – Brisbane, QLD) and Susannah Louisa Flowers (1855–1926, Portsea Island, Hampshire, England – Drummoyne, NSW) |

| Siblings | Theodore Mark Church (1886–1915, Brisbane, QLD – England) |

| Grandparents | ||||

| Paternal | John Church (1794–1860, Chewton Mendip, Somerset – East Harptree, Somerset) & Hester Currell (1802–1868, West Harptree, Somerset – Clutton, Somerset) | |||

| Maternal | Edward Flowers (1824–1873, Sussex – Hampshire) & Elizabeth Hughes (1819–1899, Portsea, Hampshire – Portsmouth, Hampshire) |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).