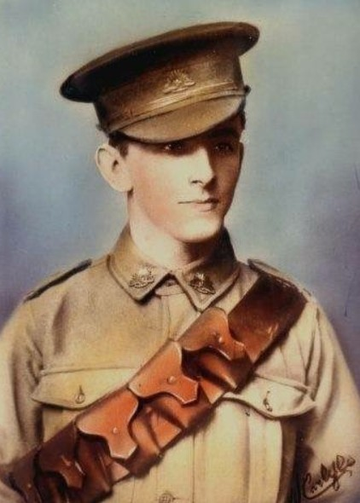

William Henry BAKER

Eyes brown, Hair brown, Complexion sallow

William Henry BAKER – A Painter, Husband and Father

Can you help find William?

William Henry Baker’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

William may be among these remaining unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in North Melbourne, VIC

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for William , please contact the Fromelles Association.

Please contact the Fromelles Association of Australia to find out more.

Early Life

William Henry Baker was born on 29 January 1890 in Williamstown, Victoria, the youngest child of George Valentine Baker (1853-1902) and Harriet Viner Newnham (1852-1928).

William’s siblings were:

- Alice (1876–1958),

- George (1878–1950),

- Albert (1881–1912),

- Augusta (1884–1955)

- and Florence (1886–1962).

His parents had married in Portsea, Hampshire, England, in 1875 before emigrating to Australia and settling in Williamstown. George joined the Royal Victorian Navy and worked as a skilled ship painter. William’s maternal aunts and uncles, also settled in Victoria, establishing strong family ties between Melbourne and Portsmouth, England.

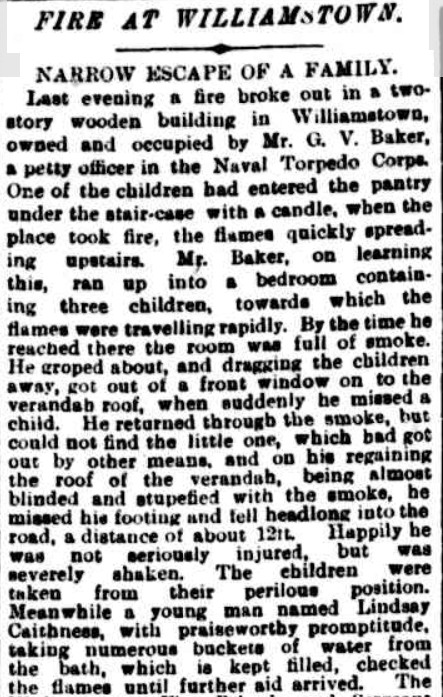

In October 1890, when William was just eight months old, a serious fire broke out in the family home at Williamstown. The blaze began when one of the older children accidentally set alight the pantry with a candle. George rushed upstairs through the smoke to rescue three of the children trapped in a bedroom, carrying them out through a window and onto the verandah roof. Thinking one child was still inside, he re-entered the smoke-filled room, but the missing child had already found her way to safety. Almost blinded by smoke, George lost his footing and fell from the verandah roof into the street below, a distance of some twelve feet. Fortunately, he survived with only bruising and all the children were saved.

Unfortunately, George died in February 1902. By the time of William’s enlistment, his mother Harriet was living in North Fitzroy. William married Violet Irene Westacott at the Presbyterian Manse in West Melbourne on 3 December 1910. She was the daughter of William Westacott and Matilda Duncan. Violet’s father, a bootmaker, had also died young. William and Violet set up home at 70 Curzon Street, North Melbourne. William, like his father, had become a painter to support his young family.

The couple had three children — Henry Binney, Daisy and Harriet Thelma May – so life for Violet would have been difficult when William went off to war. Worse yet, in November 1916, while William was still listed as missing in action, their youngest daughter died at the Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, aged just three.

Off to War

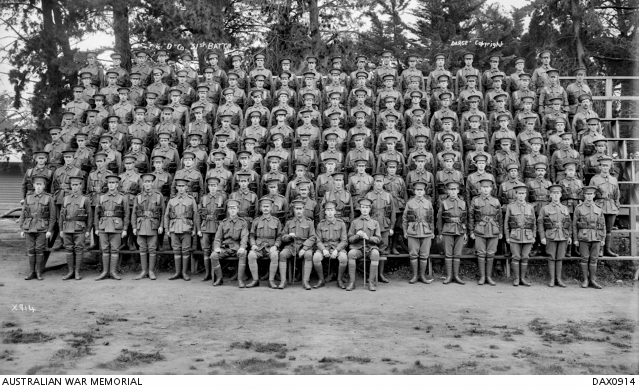

William felt the call to war and enlisted in Melbourne on 6 July 1915, leaving behind his wife Violet and three young children. He was assigned to the newly formed 31st Battalion, D Company. The 31st was made up of two companies from Victoria and two from Queensland. The Victorian enlistees first trained at the camp at Flemington Depot and then at Broadmeadows. The Queenslanders joined the Victorians in early October to complete the battalion. Before sailing from Melbourne on 9 November aboard the troopship Wandilla, the 991 soldiers of the 31st had been on parade in Melbourne in front of a good crowd. The Minister for Defence, H.F. Pearce said:

“I do not think I have ever seen a finer body of men.”

On 9 November 1915, William embarked on the HMAT Wandilla, sailing from Melbourne for Egypt, disembarking at Suez on 7 December. They were first sent to Serapeum to continue their training and to guard the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army. Near the end of February, they moved to the large camp at Tel-el-Kebir , which was about 110 km northeast of Cairo. The 40,000 men in the camp were comprised of Gallipoli veterans and the thousands of reinforcements arriving regularly from Australia. The 60 km trip must have been unpleasant, as it was reported that they were moved in “dirty horse trucks.”

Source: AWM4 23/48/7, 31st Battalion War Diaries, Feb 1916, page 5

The next move was at the end of March, back to the Suez Canal at the Ferry Post and Duntroon Camps, then at the end of May they moved to Moascar. William was promoted to Lance Corporal on 3 April 1916. Life in camp was strict and discipline was enforced, so when William was charged with neglect of duty on 5 June, he lost his lance stripe. The 31st Battalion began to make their way to the Western Front on 15 June, first by train from Moascar to Alexandria and then sailing to Marseilles. A, B and D companies were aboard the troopship Hororata and C company aboard the Manitou.

After disembarking on 23 June, they were immediately boarded onto trains to Steenbeque and then marched to their camp at Morbecque, 35 km from Fleurbaix in northern France, arriving on 26 June. The battalion strength was 1019 soldiers. The area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. Training continued, now with how to handle poisonous gas included in their regimen.

They began their move towards Fromelles on 8 July and by 11 July they were into the trenches for the first time, in relief of the 15th Battalion.

The Battle of Fromelles

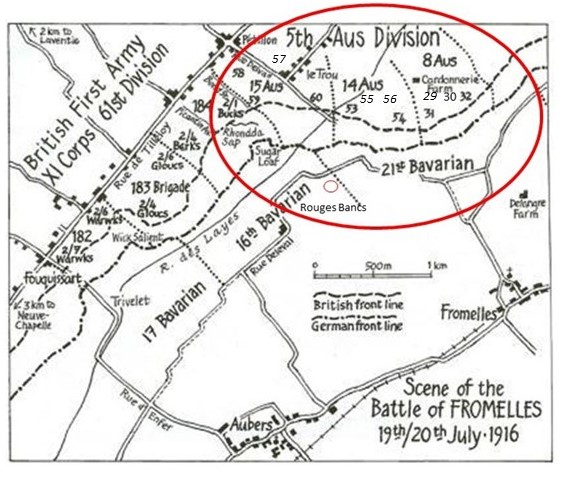

The overall plan was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The main attack was planned for the 17th, but bad weather caused it to be postponed. On the 19th they were back into the trenches and in position at 4.00 PM. The Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared:

“Just prior to launching the attack, the enemy bombardment was hellish, and it seemed as if they knew accurately the time set.”

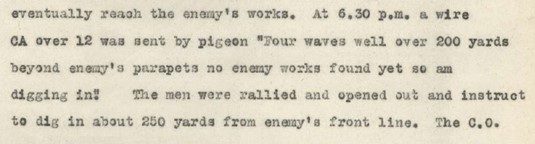

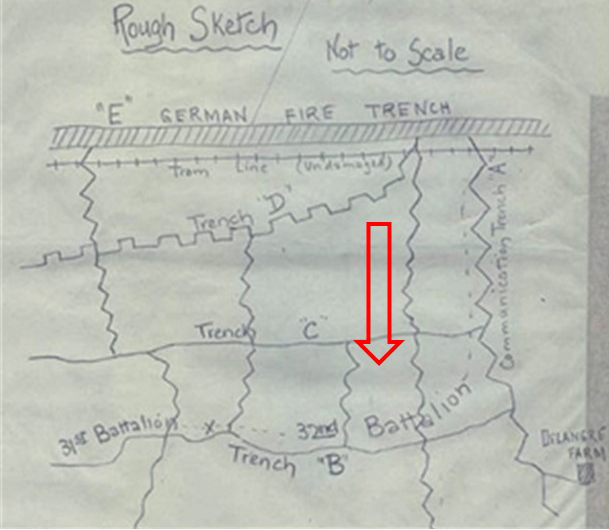

The assault began at 5.58 PM and they went forward in four waves, A and C Company in the first two waves and B and William’s D Company in the 3rd and 4th waves. There were machine gun emplacements to their left and directly ahead at Delrangre Farm and there was heavy artillery fire in No-Man’s-Land. The pre battle bombardment did have a big impact and by 6.30 PM the Aussies were in control of the German’s 1st line system (Trench B in the diagram below), which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom.”

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

Unfortunately, with the success of their attack, ‘friendly’ artillery fire caused a large number of casualties. By 8.30 PM the Australians’ left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and the 32nd, who also had the job of holding the flank to the left of the 31st, were told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine-gun fire from behind from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map).

Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, portions of the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers. At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left themselves, the only resistance the 31st could offer was with rifles:

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled a shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

The 31st were out of the trenches by the end of the day on the 20th. From the 1019 soldiers who left Egypt, the initial impact was assessed as 77 soldiers were killed or died from wounds, 414 were wounded and 85 were missing. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield.

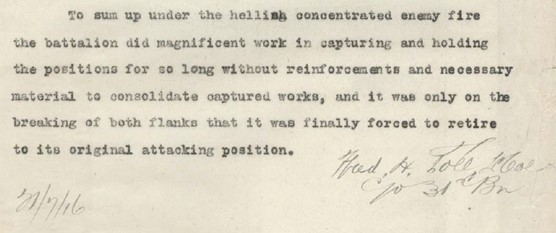

The ultimate total was that 162 soldiers were either killed or died from wounds and of this total 82 were missing. The bravery of the soldiers of the 31st was well recognised by their own Battalion commanders.

William’s Fate

Amidst this chaos, William Henry Baker was killed, but accounts differ as to his final moments. 903 Pte Reginald.W. Kitchen, D Company (15 December 1916) stated:

“I saw the soldier lying dead in their own trenches.”

1030 Pte John Southam, D Company (27 June 1917) stated:

“I was told by Pte McBain (D. Co. XIV. 31. A.I.F.) that W.H. Baker was killed (I believe shot through the head), during the attack at Fleurbaix on July 19/16. We did not take the ground and he was left in the German lines. He was a short nuggetty man about 26, medium colouring, nickname Charlie Chaplin.”

Another informant, 984 Pte John J. Williams, stated he saw Baker destroyed by an enemy shell in the trenches before the battalion even left the parapet. Finally, 797 Lt Stanley Towns, C Company (2 May 1917) said he saw William being buried:

“He was killed at Fromelles on July 19–20th. I did not see this happen but I saw him buried some 2 days later at Sailley in a portion set apart for a military cemetery.”

William’s body was never recovered. He was first reported missing, and it took until August 1917 that a Court of Enquiry in confirmed his fate - “Killed in Action, 20 July 1916.”

After the Battle

Back in Melbourne, the wait for news was long and agonising. Initially William was listed as wounded, then reported missing:

“Mrs H. BAKER, of Holden St., North Fitzroy, late of North Melbourne, has been officially notified that her son, Private W. H. Baker, who left with the 31st Battalion of Colonel Tivey’s Brigade (previously reported wounded in France), has been missing since July 20.”

For his wife Violet, the news was shattering. Left with three small children, she now faced the grief of uncertainty and the hardship of raising her family alone. That grief deepened in November 1916, when little Harriet Thelma May died at the Children’s Hospital, aged only three:

Sweet little flower, too lovely to stay, In the world’s chilling blast, so she hastened away.”

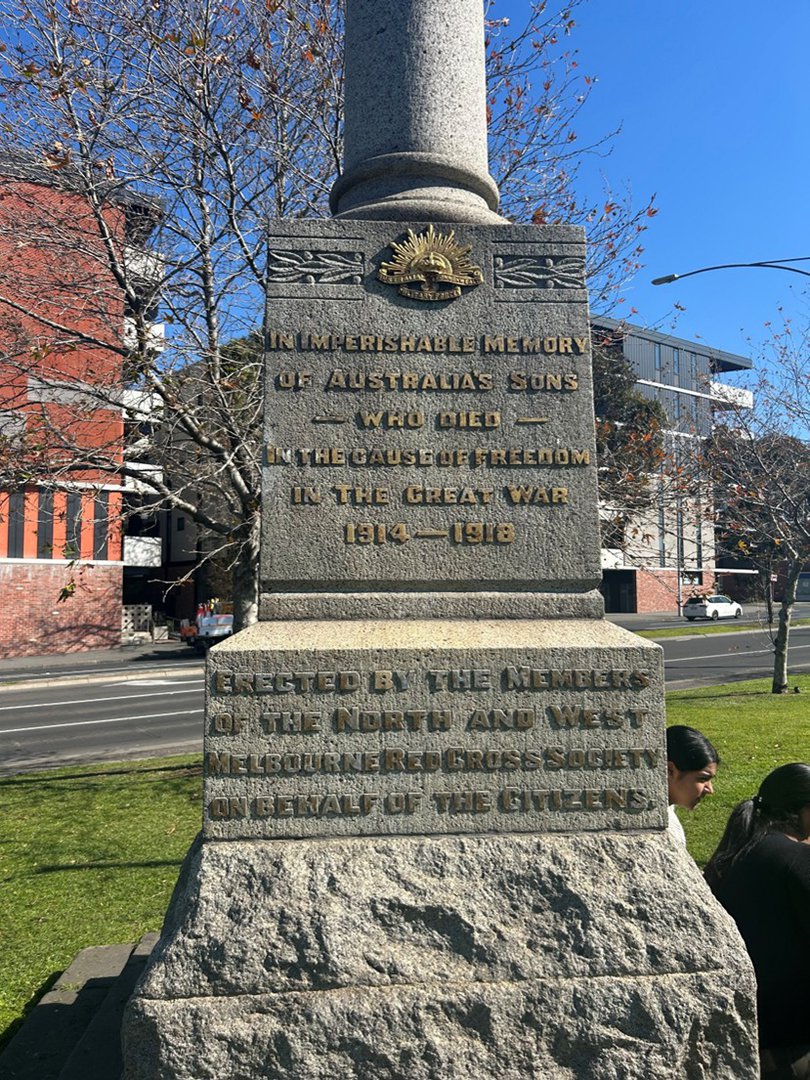

Violet received his service medals — the 1914–15 Star, British War Medal, and Victory Medal. William Henry Baker is commemorated at:

- VC Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial, Fromelles, France –Panel 3

- Australian War Memorial, Canberra – His name is recorded on the Roll of Honour, Panel 118

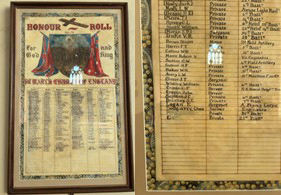

- St Mary’s Church of England Honour Roll (North Melbourne), Victoria

- North Melbourne Memorial

Finding William

William's remains have not been recovered and he has no known grave. After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including 23 of the 82 unidentified soldiers from the 31st Battalion.

We welcome all branches of William’s family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification. If you know anything of family contacts, particularly those with roots in VIC please contact the Fromelles Association. We hope that one day William will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and William’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | William Henry Baker (1890–1916) |

| Parents | George Valentine Baker (1853–1902), Harriet Viner Newnham (1850–1936) |

| Siblings | Alice Baker (1876–1958), m. George Harris | |||

| George Baker (1878–1950) | ||||

| Albert Baker (1881–1912) | ||||

| Augusta Baker (1884–1955), m. Thomas Johnston | ||||

| Florence Baker (1886–1962), m. Charles Smith |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | George Henry Baker (1829–1886), Mary Ann Drew (1832–1867), Chatham Kent | ||

| Maternal | Obediah Newnham (1819–1892), Augusta Priscilla Garrett Viner (1826–1886), Hampshire |

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).