Witton Kenworthy DALTON

Eyes blue, Hair brown, Complexion sallow

Witton Kenworthy (Ken) Dalton — A Solicitor’s Clerk, a Station Hand, a Soldier Lost

Can you help find Ken?

Witton Kenworthy (Ken) Dalton’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

Ken may be among these remaining 70 unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in Sheffield or Lincolnshire, England.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for Walter, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Early Life

Wilton Kenworthy Dalton, known to family and friends as Ken, was born in 1885 in Sheffield, Yorkshire, England. He was the youngest son of Witton Dalton and Edna Taylor. His older brother was Basil Imlay Dalton (1882–1940). Ken’s father served as the long-standing manager of the Gainsborough branch of the Sheffield Bank.

Unfortunately, Ken’s mother died in 1899 when Ken was 14. His father did remarry five years later. Ken attended St. Edward’s Grammar School in Sheffield and later Gainsborough Queen Elizabeth Grammar School. When he was 15, he was listed among the successful candidates in the Incorporated Law Society’s Preliminary Examination, published in The Solicitors’ Journal. In the 1901 Census, 16-year-old Ken was living with his widowed father at 12 Silver Street, Gainsborough, and was working as a solicitor’s articled clerk.

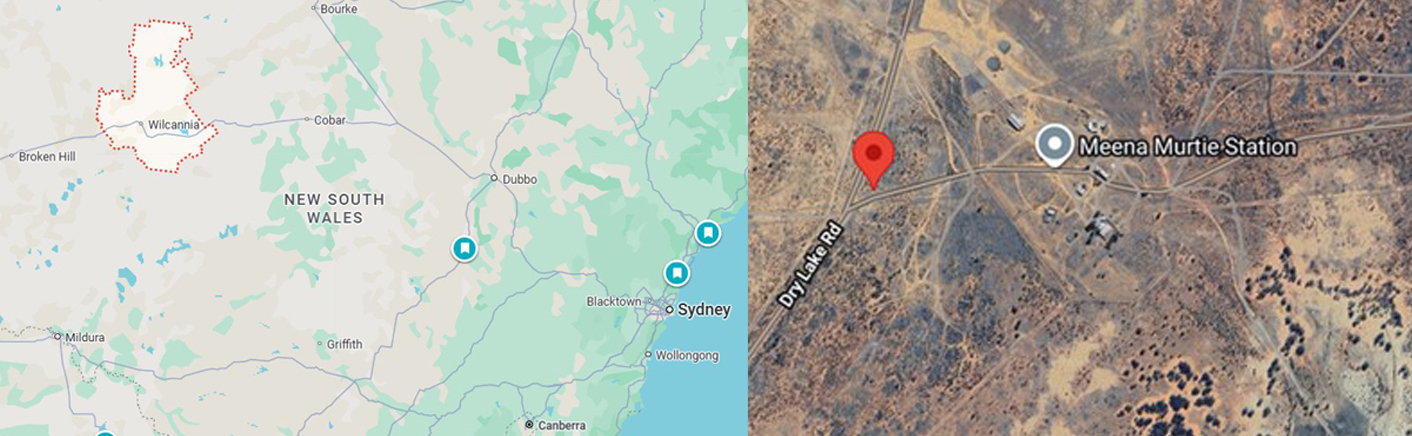

The 1911 Census shows Ken living with his aunt, Ellen Taylor, in Ecclesall, Yorkshire, and working as a solicitor. At some point after this, Ken chose to emigrate to Australia. By 1913, the New South Wales electoral roll listed him working as a station hand at Mena Murtee near Wilcannia, NSW, a thousand kilometres from Sydney, a marked change from his legal career in England! This move is reflective of a number of educated young Britons seeking opportunity in Australia’s pastoral and agricultural industries before the outbreak of the First World War.

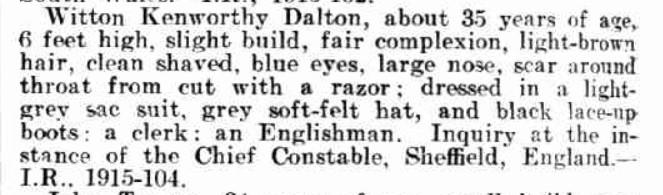

His records do contain an intriguing 1915 “Missing Friends” note from the New South Wales Police Gazette of March 1915 , which lists a “Witton Kenworthy Dalton” (matching his description) as the subject of an inquiry by the Chief Constable of Sheffield, but nothing further is known about this. (note- no scar noted on his enlistment records)

Off to War

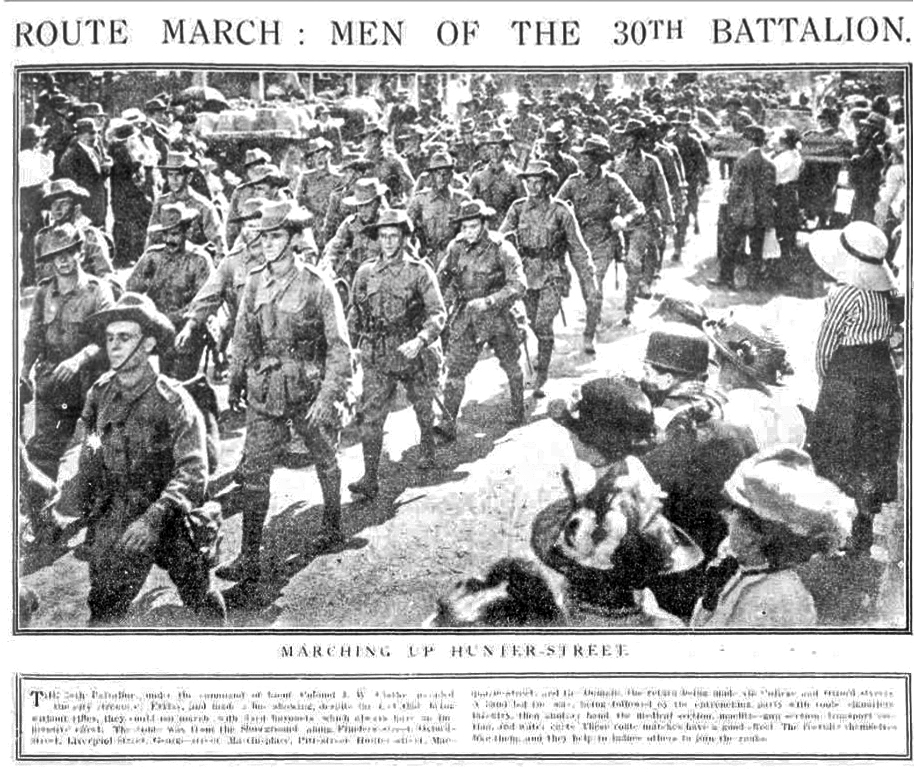

Ken travelled all the way to Liverpool, New South Wales to enlist in the Australian Imperial Force on 21 July 1915. He was assigned to D Company of the newly raised 30th Battalion. His military training commenced in the Liverpool camp, but in September they moved to the Royal Agricultural Show Grounds in Moore Park, Sydney. There were numerous reports of their activities in the papers.

The battalion left Sydney for Egypt aboard HMAT A72 Beltana at 3.30 PM on 9 November 1915. Their trip was uneventful and they disembarked in Egypt on 11 December, joining the AIF forces consolidating there after the Gallipoli evacuation. Their first seven weeks were spent at Ferry Post continuing their training and guarding the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army.

February and March were spent at the 40,000 man camp at Tel-el-Kebir, 110 km northeast of Cairo. While there, they were inspected by H.R.H. Prince of Wales.

For much of April and May were back in Ferry Post, including some time in the front-line trenches there. There were the usual complaints of the heat, water supplies and flies. The battalion left Egypt for the Western Front on 16 June 1916 on HMAT Hororata and arrived in Marseilles on 23 June. After landing, they were immediately entrained for a 60+ hour train ride to Hazebrouck, 30 km from Fleurbaix. They arrived on 29 June and then encamped in Morbecque.

Private F.R. Sharp (2134) wrote home:

“From the time we left Marseilles until we reached our destination was nothing but one long stretch of farms and the scenery was magnificent.” “France is a country worth fighting for.”

The area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. Training now included the use of gas masks and they also would have heard the heavy artillery from the front lines.

On 8 July they were headed to the front lines, first to Estaires, 20 km and the next day 11 km to Erquinghem, where they were billeted at Jesus Farm. They got their first ‘taste’ of being in the front lines at 9.00 PM on 10 July. A week later, they got orders for an attack, but it was postponed due to the weather.

In his final letter home Charles Albert Woods (2194, 30th Bn) summed up the situation he found himself in:

“Since writing last we have shifted from ‘somewhere in France’ to ‘somewhere else in France,’ and are now in the trenches. Whilst writing this the shells are whistling over our heads a ‘treat.’ We are all provided with steel helmets to lessen the danger of being hit in the head with shrapnel, and also with gas helmets, to put on while a gas attack is being made on us.”

Then, on 19 July, the 29 officers and 927 other ranks of the 30th Battalion were into battle.

The Battle of Fromelles

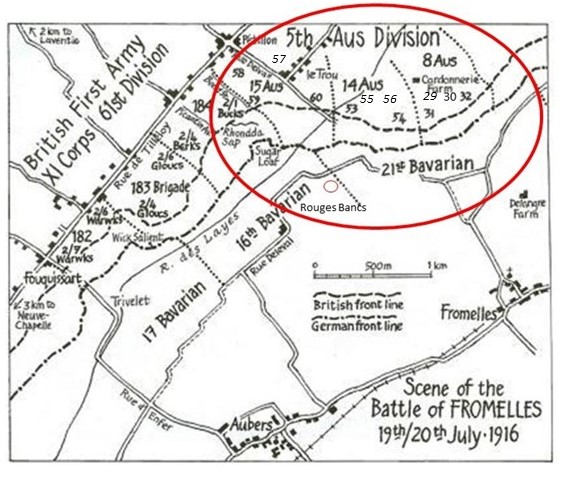

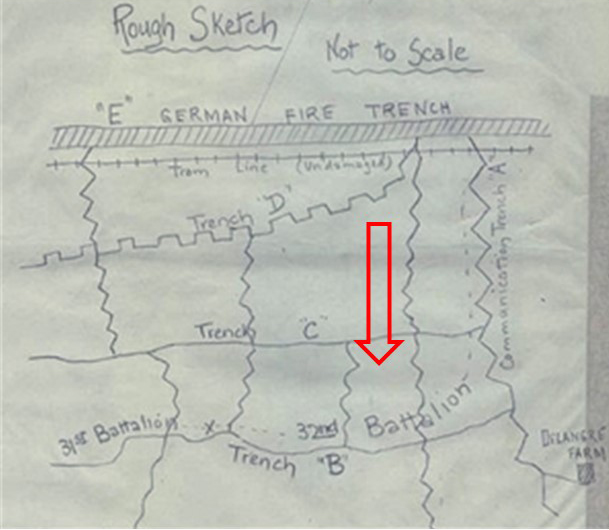

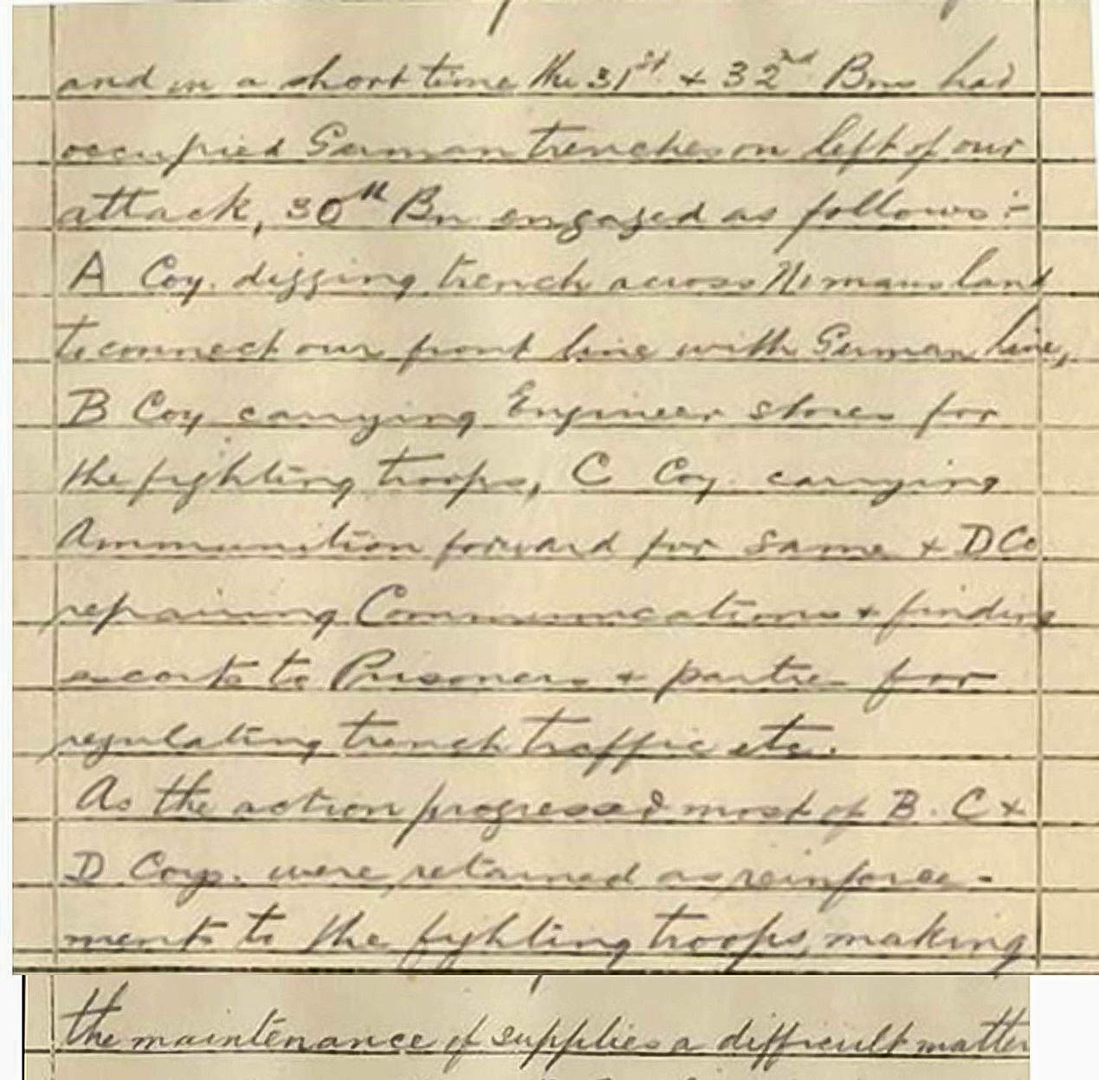

The overall plan was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The 30th Battalion’s role was to provide support for the attacking 31st and 32nd Battalions by digging trenches and providing carrying parties for supplies and ammunition. They would be called in as reserves if needed for the fighting. On 19 July, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared.

They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. The 32nd’s charge over the parapet began at 5.53 PM and the 31st’s at 5.58 PM. There were machine gun emplacements to their left and directly ahead at Delrangre Farm and there was heavy artillery fire in No-Man’s-Land. Ken and his mate Sergeant Gordon Begg (839) entered the fray bravely.

Gordon said:

“He was my mate from the day we enlisted. On the afternoon we were going to the attack we shook hands and wished each other luck, walked to the line and jumped over the parapet.”

The initial assaults were successful and by 6.30 PM the Aussies were in control of the German’s 1st line system (Trench B in the diagram below), which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

While Ken’s role was to be in support, commanders on scene made the decision to use some of the 30th as much-needed fighting reinforcements. A necessary act, but it had consequences as it interfered with the planned flow of supplies.

By 8.30 PM the Australians’ left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and they were told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page.

When the 30th was formally called to provide fighting support at 10.10 pm, Lieutenant-Colonel Clark of the 30th reported:

“All my men who have gone forward with ammunition have not returned. I have not even one section left.”

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine-gun fire from behind from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map).

Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, portions of the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers. At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance the 31st could offer was with rifles.

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

By 10.00 AM on the 20th, the Germans had repelled the Australian attack and the 30th Battalion were pulled out of the trenches. The nature of this battle was summed up by Private Jim Cleworth (784) from the 29th:

"The novelty of being a soldier wore off in about five seconds, it was like a bloody butcher's shop."

Initial figures of the impact of the battle on the 30th were 54 killed, 230 wounded and 68 missing. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The ultimate total was that 125 soldiers of the 30th Battalion were either killed or died from wounds and of this total 80 were missing/unidentified.

Ken’s Fate

Ken was very active in the 30th’s risky role of providing support:

“carrying under heavy fire ammunition across No Man’s Land up to midnight to a German trench our forces captured…”

But, given the chaos of the battle, there is little hard evidence of exactly what happened to Ken. Private Thomas J. Clancy’s (1331) witness statement said:

Dalton was wounded in the arm at Fleurbaix. Informant tied it up.

Lance Corporal Percy Wright's (1000) statement suggested he was wounded, but thought he had been taken prisoner:

“On 20th July 1916 at about 6 p.m. at Fromelles we retired. Dalton, who was in my section, was, according to information given to me by men in the company, last seen alive but wounded in the German trench. It was believed he was taken prisoner.”

There are no witness statements about him actually being killed. His mate Sergeant Gordon Begg concisely sums up the battle from a soldier’s point of view:

“The night of the attack was dreadful – such a mixed up affair I hardly like to recall it.”

Family and friends after the battle

Ken’s brother Basil was in regular contact with the authorities seeking information about what happened to his Brother.

He first wrote on 4 September :

“On the 15th August we received the official intimation from the A.I.F. Administrative Headquarters that my only brother, No. 867 Private W.K. Dalton, A Coy, 30th Batt., A.I.F., was reported as missing after being in action with the B.E.F. …”

“…After that, though every possible enquiry had been made before writing to us, no trace of him could be found.

The official dispatch from G.H.Q. on 2.50 p.m. July 20th makes it probable that the action in which he was present took place south of Armentières. Any information you may receive of him, I should – needless to say – be most grateful to hear.— Basil I. Dalton, 111 Union Road, Brincliffe, Sheffield, England

In October, the Red Cross gave Basil contact details for Ken’s mate Gordon Begg and several others. In January, Gordon provided the Red Cross more information and advice that he would be in England and would be happy to provide further details to the family:

“He was my mate from the day we enlisted.”

“Am over in London in on duty arrived here Christmas day and will be here for about six months so if I can give you any information of if Dalton's relatives would like to know anything, they can see me or write me at the address below.”

“The night of our attack was dreadful it was such a mixed up affair that I hardly like to recall it again, but their minds must be eased. I shall only be too pleased to do anything I possibly can for you.”

In February 1917, Ken’s Aunt Ellen sent the Red Cross a photo of Ken, Gordon and four mates taken at their departure from Sydney. Presumably this made it to Gordon. It is not known if the family ever did meet with Gordon, but Gordon’s commitment to do the right thing for Ken’s family is admirable - a true mate. Ken was formally declared as Killed in Action on 20 July 1916 in a Court of Enquiry held on 23 July 1917.

After the Battle

After his father passed away in 1924, Ken’s family in Lincolnshire ensured his name was added as a memorial to the family headstone in North Warren Cemetery, Morton.

Ken is commemorated at:

- V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles, France (Panel No. 2)

- North Warren Cemetery, Morton, Lincolnshire, England – family headstone inscription

- St. Andrew’s Church Roll of Honour, Sheffield, England

- Gainsborough Queen Elizabeth Grammar School Roll of Honour

- Scottish National War Memorial, Edinburgh Castle, Scotland

Finding Ken

Ken’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles and there are no records of his burial. A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing, including 26 of the 80 missing soldiers from the 30th Battalion. Ken may be among these remaining 70 unidentified men.

There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in Lincolnshire or Sheffield, England. See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family. We hope that one day Ken will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Ken’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Witton Kenworthy Dalton (1884–1916) |

| Parents | Witton Dalton (1851–1924) and Edna Taylor (1850–1899) |

| Siblings | Basil Imlay Dalton (1882–1940) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Witton Dalton (1815–1885) and Avice Imlay (1814–1874) | ||

| Maternal | William Taylor (1808–1861) and Edna Kenworthy (1813–1874) |

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).