Henry Victor WILLIS

Eyes blue, Hair brown, Complexion sallow

Harry Willis, a farm boy gone to war

Settle in for a good read as Harry’s story is a complex and multi-faceted one. It involves brothers who were also fighting on the Western Front, multiple generations of his family impacted by his loss, family involvement in Lambis Englezos’ research team and a lucky charm that helped build evidence across the decades of the link between Fromelles and Australia. The first part focuses quite rightly on Harry, his life and his family while the second part concentrates on the broader Fromelles research story and family member Tim Whitford’s close involvement.

Our thanks go to Tim for much of the content of this story. It includes a blending of material written by Tim firstly for author, Patrick Lindsay, who included Tim’s work as an epilogue in his book ‘Our Darkest Day’ (2011, Hardie Grant, pp 201-211) and secondly, for an FFFAIF newsletter article Uncle Harry's Charm posted 8 July 2008.

Henry Victor 'Harry' Willis was born in 1895 in the South Gippsland town of Alberton in Victoria. Photos of him are cherished by his family as they show him with the faint glimmer of a smile. Harry was a 20-year-old soldier in the 31st Battalion, Australian Imperial Force (AIF), which was allotted the task of being the right-forward assault battalion of the 8th Brigade in the Battle of Fromelles.

Harry enlisted on 14 July 1915 in Yarram Yarram just north of his family home in Alberton, Victoria. He was allocated service number 983 and embarked from Melbourne, Victoria, on board HMAT A62 Wandilla on 9 November 1915.

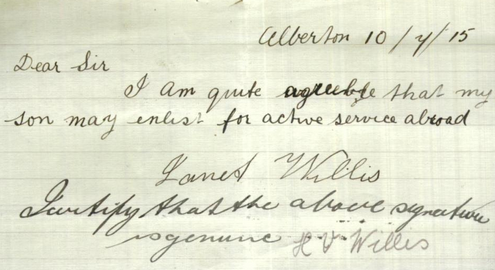

Harry was a good-looking boy and always had a smile on his face. He was extremely youthful in his looks and was a hard worker. He worked as a general labourer on the family farmlet and helped on other farms around the district. Harry’s brothers Bert, George, David and Syd all joined the AIF when war came and after receiving a white feather in the post, Harry soon forged his mum’s signature (he was 19 years old – under aged at the time) and joined up as well.

Janet mustn’t have minded too much as she never sought to have Harry discharged in the months that he was at Broadmeadows camp. I guess money was tight, so the extra really helped.

Harry became an original member of D Company (OC Captain Mills) of the 31st Battalion (Lt Col Toll), 8th Brigade (General Tivey), and was eventually trained as part of a Lewis Gun team. We think Harry was proud of being a soldier. Although he never wrote much, he sent many portraits home to the family.

Harry, with the rest of the 8th Brigade, missed out on the Gallipoli campaign and spent an extended period of time training in Egypt before sailing for the Western Front.

The 31st Battalion was allotted to the attack on Fromelles shortly after its arrival in France, and it was while marching up to the Fleurbaix sector that Harry and his older brother Syd had a chance, final meeting. Syd had been in a neighbouring sector with the 21st Battalion and was on a carrying fatigue when the two met. Both brothers knew that Harry’s chances weren’t good and one can only imagine what it feels like, in a few snatched moments, to shake hands and say goodbye to a little brother for what they knew might be the last time.

Harry at War - The Attack at Fromelles

The designated time for the attack to commence, zero hour, was set for dusk, which General Haking had decided was at 6 pm. However, in France in July the sun sets hours later - anywhere between 9.30 pm and 10 pm - so when the battalion filed through the sally ports into no-man's land at 5.58 pm, the boys of the 31st Battalion had to endure three hours of daylight under the eyes of the German machine gunners and artillery forward observers.

Being in the battalion's second wave, Harry didn't leave with them. As the two assault companies hopped the bags, Harry and the second wave moved up from the 300-yard line to the now vacant front line to endure another quarter of an hour of nerve-shattering waiting under artillery fire, not only from German guns but also short-firing Australian guns which - despite urgent pleas to lift their fire - continued to fire on the Australian parapet. The nervous tension among the waiting troops of the second wave would have been exacerbated by the cries of the wounded and the constant crackling of small-arms fire and the dull crumps of the merciless grenade duels as the first wave tried to clear the enemy troops from the stronghold.

At 6.14 pm the order for the second wave to attack came. Harry was a member of a Lewis gun team and his gun-crew mate was 20-year-old Private Henry Rogers, a former draper's assistant from Taree. They went through the sally port together heading toward the muzzle flashes and gunfire just under 120 yards to their front. The need for hand-grenades and machine-guns had become desperate. The Battalion was holding on by its fingernails and was slowly being bombed and sniped out of existence.

Lieutenant Colonel Toll realised that his position was almost untenable as the fierce fight to keep a toehold in the enemy line in front of a strongly fortified farm ruin known as the Grashof, reached critical point. It was possibly fire from this position by German machine gunners that killed Harry. Harry’s mate, Private Henry Rogers, was certain that he had seen Harry shot. We know from eyewitness accounts that Harry received a jaw wound. It was this wound or shock that probably killed him.

Harry Missing - later Killed in Action

Whatever the exact sequence of events, Harry was killed and his body went missing in battle in mid-July 1916. As Tim says, “Harry is no different to thousands of others, but Harry is a relative, my great-great-uncle and, he's special, very special to me.”

At the time of the Battle of Fromelles, his brothers Syd and Bert were both stationed in the Fleurbaix area. When young Harry was reported missing, they must have been frantic trying to discover what had happened to him.

Eventually, authorities were notified that Harry’s name appeared on a German Death List and he was found to have been killed in action. The German authorities returned his identity disc and it was sent back to Australia in late 1917 – and presumably forwarded to his mother as next of kin.

Tim Whitford’s personal Fromelles Journey

Background: Tim was a Sergeant in the Royal Australian Armoured Corps, and in particular the First Armoured Regiment. During his career he served overseas including an attachment to the British Army in the Queen’s Dragoon Guards in Westphalia, Germany and in the Republic of Cyprus. After his military career, Tim was Operations Manager, Security Manager, Education Outreach Officer in the Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne. Now Tim is Veterans’ Advocate / Pensions Officer for the Returned and Services League (Victoria).

Tim, Nan and Uncle Harry

I grew up in the South Gippsland town of Yarram, just three kilometres from the old Willis house in Alberton. Mum and Dad were wonderful parents and hard workers, they had to be; they were battlers always with an eye on the bottom line. Dad was a rural merchandise man and Mum a nurse. Both worked full-time and it was my grandparents who became a constant in my early life.

My Nan and Pa would mind me during the day and I'd sometimes eat tea at their house. Nan would dote on me and Pa was always deconstructing some object or machine just to find out how it worked. His shed was an Aladdin's cave of paint cans, strange machines, typewriters and jam jars full of old nails and screws. One night we were sitting at the kitchen table when Nan asked me what I wanted to do with my life. I was eight years old and immediately replied 'I want to be an army man, Nan'. She immediately shot back with 'Don't you dare be a soldier! You'll be killed like my uncle Harry. He got shot up and we don't know where he is.' This reaction from a loving and gentle woman cut to my core and has stayed with me ever since.

My Nan was born the year Harry died. Growing up in the postwar environment, Nan could not possibly avoid being imprinted with Harry and his legacy. 'Harry' was passed directly to me by her. It's something that only she and I share. There was no formal handover, or even many words spoken, but as I grew up and my interest in Harry grew deeper and stronger, I know Nan was quietly and deeply pleased.

Like Harry, I enthusiastically volunteered to serve Australia, and despite the worldly-wise warnings of my own grandmother, I served as an Australian soldier for over 14 years. Like Harry, I've felt the pride of wearing the slouch hat and the rising-sun badge of my country.

1996 First visit to Fromelles

I first visited Fromelles in 1996. We drove down to VC Corner Cemetery in the centre of the old Australian battlefield. The burials at VC Corner are unidentified except for their nationality. All 410 burials in the cemetery are Australian, buried in two large grave plots overplanted with 410 roses. This makes it the only all-Australian cemetery in France and the only Commonwealth Cemetery in France without headstones.

Along the back of the cemetery is a memorial wall made from black flint and white Portland stone. This wall commemorates the men killed at the Battle of Fromelles who have no known grave. Reaching the wall I quickly sought out the panel commemorating the Diggers from the 31st Battalion. There were many names up there on the panel that had become familiar to me from my years of research but as my eyes moved down the list I despaired of [not] finding my relative's name. The disgrace and bungling of the Battle of Fromelles was affecting me personally, decades after the event itself. Walking out onto the battlefield, I couldn't stop asking myself: “Where are you, mate? I know you are here, but where?”

I was the first family member to have gone to Fromelles to pay tribute to a missing soldier. For that reason alone, the pilgrimage was entirely worthwhile. However, there were far too many unanswered questions. Why did Harry and the names of a couple of dozen other men of 31st Battalion end up on the Australian National Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux, hundreds of kilometres from Fromelles, out of context and separate from their mates, when the rest were commemorated at VC Corner in the centre of the battlefield?

1997 Fromelles

In March 1997, I returned to Fromelles with a mate and fellow Great War history buff, and also my Troop Sergeant, Graeme Walker. We spent eight or 10 days following in the footsteps of the Diggers in what was probably my most enjoyable trip to the battlefields.

A week later, and after laying a poppy on the VC Corner Cross of Sacrifice in Harry's memory and walking the battlefield, we went to the Gallodrome Café in the centre of Fromelles. We were having a good time and we decided that, having eaten and conversed with the Fromellois in our limited French, we'd say our farewells and be on our way. But Madame behind the counter had decided that we weren't to leave and wildly gestured that we sit down again. We had no idea why Madame didn't want us to leave; but we weren't in France to be rude so we just accepted that we had to wait. Soon after, we were introduced to Henri Dellepierre, who had parked his equally elderly bike against the wall of the café.

We were taken on a most wonderful tour of the Fromelles battlefield. Henri was at pains to ensure that we walked in fields where tourists would normally not dare to go and he insisted that we collect souvenir buttons, bullets and shrapnel balls.

After being taken on a zigzag course through a series of secondary roads, we were told to park and we all alighted and were led a short distance to what looked like a pile of old rubbish at the edge of a paddock. It was a concrete staircase and we were led down a few metres until we reached a large room. It had a funnel-shaped half-circular aperture in the thick reinforced concrete ceiling. The aperture was where the heavy mortar bombs would fly out from beneath the surface to rain death on anyone attacking the German front. Henri explained that L'Association pour le Souvenir de la Battaille de Fromelles or ASBF had only recently discovered this position and that when they'd pumped out the water, they'd found it literally full of intact war items. The haul included many unexploded heavy mortar bombs including 20 live poison gas bombs.

I didn't know it at the time but the little secondary road we had driven to the mortar position was the left-hand boundary of Harry's 31st Battalion during the attack all those years ago. The place where we'd parked our car to walk to the mortar position was where the Germans had stopped the Australians that night. In 1916 our car would have been parked adjacent to piles of dead Diggers and the site of a grenade fight.

After that, there'd be other visits to Harry’s battlefield. Many more.

2006 Lambis Englezos’ – his theories and his passion

At home in Tallarook, on 18 July 2006, I heard Lambis Englezos’ theory that a large number of Diggers who had fought their way into the German positions and were killed during the Battle of Fromelles had been later gathered up and buried in mass burial pits behind the lines by the Bavarians. Lambis believed he had found them and had aerial photos of the pits to prove it.

Lambis and I spoke many times in the weeks that followed. One day he invited me to meet his co-researcher, Ward Selby. They were planning their pitch to the panel of experts assembled by the Army History Unit.

I had been studying military uniforms, equipment, weapons, and tactics for many years and it was quickly realised by Lambis and Ward that this knowledge was of value. Additionally, my 14 years as a combat-arms soldier meant that I viewed maps, military documents and photographs with a completely different eye than conventional historians. Lambis and Ward were looking at the pits on one of the aerial photos which were crucial to the argument that the pits were mass burial sites. Lambis and Ward were bogged down. The Army History Unit had said that the pits in the photos might just as likely be mortar pits or defensive works. I chuckled audibly and they did a double take. I said:

“Those pits are symmetrically dug; they're in the open even though there's a perfectly good forest not five metres from them. There's been no attempt to hide them at all and they are oriented in the wrong direction to be mortar pits. Aerial reconnaissance was a reality in 1916 and yet there is not a single sign that the Germans cared who saw them ... they're graves.”

Another similar bit of photo interpretation happened when Lambis showed me a photograph of a trench full of dead soldiers. He had a theory that this was a photo of dead Australians in a pit at Pheasant Wood. I quickly said, 'No, mate, they are British soldiers. See the brass buttons and the fitted tunics.' From that time on I was in with both feet.

2007 The GUARD team preliminary research

On 16 May 2007 the archaeological team started work at the Pheasant Wood site. It had been a long haul to get them there. Tony Pollard was the head of the Glasgow University Archaeological Research Division (GUARD) team. They had a great reputation and were commissioned by the Australian Army to determine whether Pheasant Wood had been a burial site, its extent, and most importantly whether it remained a burial site. The team conducted an array of tests but they had to be non-invasive - that is they must not dig for remains. The only digging allowed would be in the top few inches of the field.

The metal detector sweeps proved to be the most enlightening of the many tests conducted. There was a wide scatter of metallic wartime artefacts detected across the site, unmoved since the end of the Great War, proving that - beyond reasonable doubt - the site remained undisturbed and that in all probability the burial pits remained intact.

And as noted in Harry’s story, one of the many artefacts found was the tiny, enamelled Alberton Shire good-luck medallion identical to the one presented to Harry and other recruits from the Alberton Shire. This little lucky charm was to prove key evidence in linking Australian soldiers (and Harry) to the Fromelles site.

Alongside Lambis, I advocated through the media to accelerate the investigation process. Initially, I was unsure of myself when speaking to journalists but I became more confident and constantly evoked the name of Harry Willis. I figured that the best way to get the job done was to give the public a name to hang onto -to make it about real people, not just about history. It was working. The media grabbed two things from then on: lone crusader Lambis winning in spite of Big Brother; and Harry Willis and his miracle medallion, is he there? His relative is certain he is.

2008 The Dig

The site at Pheasant Wood had been a burial site. Australian soldiers had been buried there. Were they still there? Probably, but only the shovel could really give the answer. So, it was to be. The Australian Army would return to Fromelles in the European summer of 2008 and this time they were going to dig.

The site was about 200 metres long and about 40 metres wide and was surrounded by recently erected temporary fencing with a little portacabin brew-room-cum-office at the nearest end to the access path. About a third of the site was roped-off. The small mechanical excavator was fired up and Garry Andrews, the operator, with incredible skill began to peel layer after layer of inch-deep butter curls of earth from the first trench.

It had taken 92 years but finally they were here, and they were digging!

The outlines of the pits were showing strong and straight against the ploughed soil as Gary Andrews' excavator continued peeling back the layers of soil. As the layers were removed, the tension grew. It was tangible. What if they weren't there? This was the single biggest project that Tony Pollard had ever undertaken, and it carried the greatest personal risk for him too if the pits were empty.

Then, on the second night of the dig, on 27 May 2008, there was a distinct change in mood on site. We sensed that they had found them but weren't announcing it yet. The next day confirmation came for me in the form of a text message from my mate Col Strawbridge in Australia: 'Congratulations mate. You've done it. We are so proud of you.'

I immediately rang him and he confirmed that human remains had been found. My wife Liz, daughter Alexandra and I immediately drove to the site. We arrived just in time for Tony and General Mike O'Brien, the army's project leader, to announce to the gathering press that at around 5 pm the previous evening the first human remains had been uncovered. General O'Brien announced that the site had progressed from a place of historical interest into a place of much deeper significance to the nations of Great Britain and Australia.

2010 Claiming our Diggers

Since the 2008 dig we had agitated hard to ensure that the Diggers, including Harry, weren't left in those pits and were afforded a proper attempt at identification and a military funeral. Thankfully that occurred.

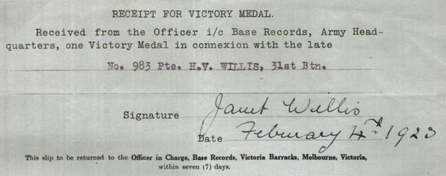

In July 2010, I returned to Fromelles. It was the culmination of a long journey and many questions had been answered. The army had been splendid. A new cemetery had been built; families had come forward from Australia and the world, offering their family trees and DNA to give the Diggers a chance of regaining their identity. The soldiers had been reburied the previous winter. On 17 March 2010 the first of the names of those identified, Harry's among them, were announced. Nan's DNA had helped identify him. There was just one unknown soldier left to be reburied with full military honours and fanfare on the anniversary of the battle.

Harry and his mates had been given their final resting place, just as we had wished.

Links to Official Records

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).