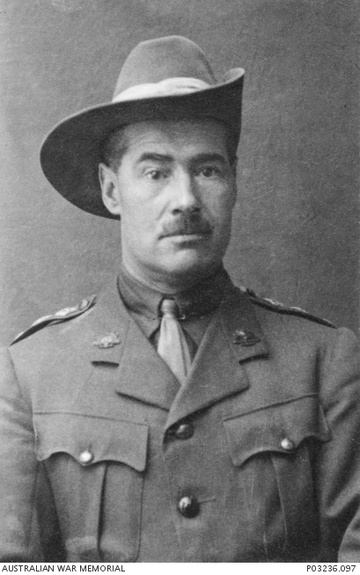

Charles MILLS

Eyes hazel, Hair brown, Complexion dark

Fromelles and the Later Humanitarian works of Capt Mills

When researching a soldier’s records for the Soldier Stories of Fromelles, there is one item that comes up (all too) often – a note from a Capt Mills. This is his story.

Charles Mills – His early life

Charles Mills was born in Cheltenham Victoria on 17 July 1876 to Mary Ann (nee Carter) and John Mills, the seventh of their nine sons. John and Mary Ann were farmers in Heatherton, near Cheltenham, Victoria.

Charles unfortunately lost his mother when he was 6 years old and his youngest brother was only 2. His father, John, remarried a year later – to Eliza Noy, and they had another two sons. A family of eleven boys!

While Charles went on to have a very notable military career, his older brother Roderick 1869-1940 became more widely known at the time.

Charles’ brother: “Saltbush Bill” Roderick Hill 1869-1940

At 14 years old, Charles’ brother, Roderick, moved to Queensland. He was an excellent horseman spending many hours out in the saltbush on his horse. The station owner he worked for dubbed him ‘Saltbush Bill’, and he is said to have provided inspiration for Banjo Paterson’s Saltbush character.

Roderick also developed a reputation as a champion whip-cracker, touring the country in roughriding shows and doing vaudeville. He even attracted the attention of King George V during a tour of Australia and the King invited “Saltbush Bill” to perform at Buckingham Palace. After a full routine of his tricks, the finale was cracking out several bars of “God Save the King” on his 65-foot whip.

Roderick married and lived in Heatherton where he and his wife, Hannah, had a family of eleven children.

Source: Peninsula Essence 16 January 2019, ‘Saltbush Bill’ – the Balnarring connection

In 1899, Charles married Jessie Cameron 1876-1929 and had four children – Alex 1900-27, Florence 1904-36, Glennie Millicent 1905-76, and Ronald 1910-10.

Early Military Career

In his teens, Charles served for four years in the senior cadets and he had “in every way, proved himself a thorough soldier”. He also won first prize in the Senior Cadet Rifle matches three years running and was described by his commanding officer as “the best shot in the senior cadets”.

Source: NAA: B2455, MILLS, Charles – First AIF Personnel Dossiers 1914-1920, page 45.

After he finished school, in which he earned a 1st Class Certificate of Education, he worked for a while as an electrical fitter, but then chose to pursue a military career. Charles enlisted in the Royal Australian Artillery in early 1896 with his first five years as a gunner and a bomber. His first promotion to Corporal was in mid-1901. In 1906, he became a Sergeant Electrician. In 1909, he moved to the Royal Australian Engineers and by early 1915 had become a Warrant Officer.

Off to War

The Australian Imperial Force was formed in late 1914 for support of the War in Europe and experienced military men were in demand. In August 1915 Charles was transferred to the AIF and assigned to the 31st Infantry Battalion, initially as a Lieutenant, but was promoted to Captain in October. They departed for Egypt on 9 November and arrived in Suez on 7 December. Their time in Egypt was spent training and guarding the Suez Canal.

On 15 June 1916, the 31st began to make their way to the Western Front, first by train from Moascar to Alexandria and then aboard the troopship Hororata, sailing to Marseilles. After disembarking on 22 June, they took trains to Steenbeque, 35 kilometres from Fleurbaix, arriving on 26 June.

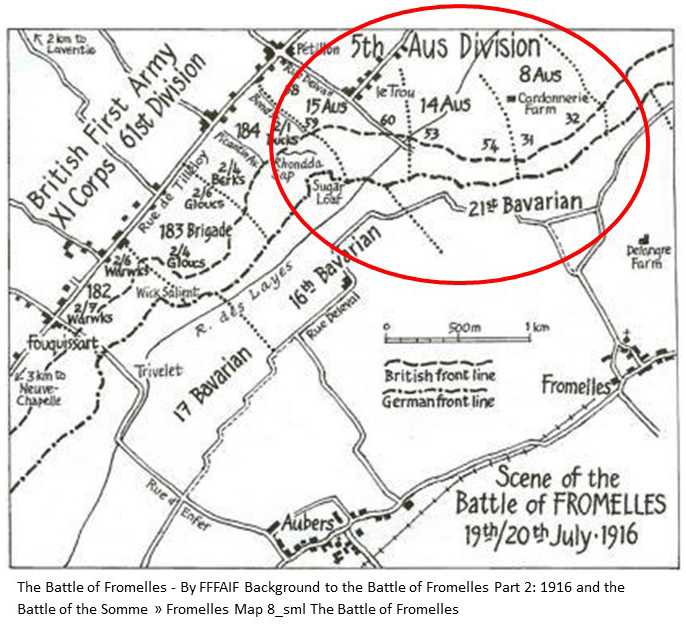

After settling in and continuing their training and planning for an upcoming attack, they were into the trenches for the first time on 11 July. The battalion strength was 979 soldiers.

The original plan for an attack was on July 17th, but bad weather caused it to be postponed.

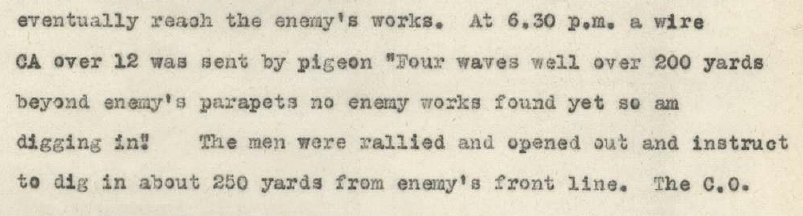

Charles was in the front line on the 19th and at 4.00pm the 31st were in position for their attack. Their assault began at 5.58pm, with four waves of men going over the parapet. According to the battalion’s war diaries (AWM):

“Just prior to launching the attack, the enemy bombardment was hellish, and it seemed as if they knew accurately the time set.”

The pre-battle bombardment had a significant impact on German first line trenches and the 31st quickly advanced to the second line, which was mostly ditches filled with water. Even with the initial support, they remained under heavy artillery from both sides.

Unfortunately, with the speed of their advances, ‘friendly’ artillery fire caused a large number of Australian casualties. They were able to take out a German machine gun, but they were being seriously enfiladed from their left flank. Fighting continued throughout the night, with heavy firing from concealed machine guns from Delangre Farm and houses.

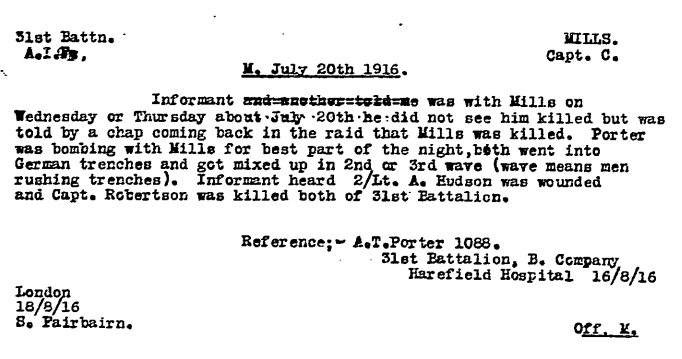

Private Albert Porter (1088) said he was bombing with Mills for the best part of the night and he confirmed that they had advanced into the German trenches.

At first light on the morning of 20 July 1916, German soldiers had showered Charles’ position with grenades before rushing in from the flanks, firing their rifles from the hip and overwhelming the soldiers. Charles’ right hand had been lacerated during the attack.

A German NCO stopped his men on the parapet, jumped into the waterlogged ditch and seized Mills by his wounded hand. ‘Why did you not put up your hands, officer?’ he asked.

The rest of the 31st were out of the trenches by the end of the day on the 20th. The headcount was just 512 soldiers of the 979 who began the battle.

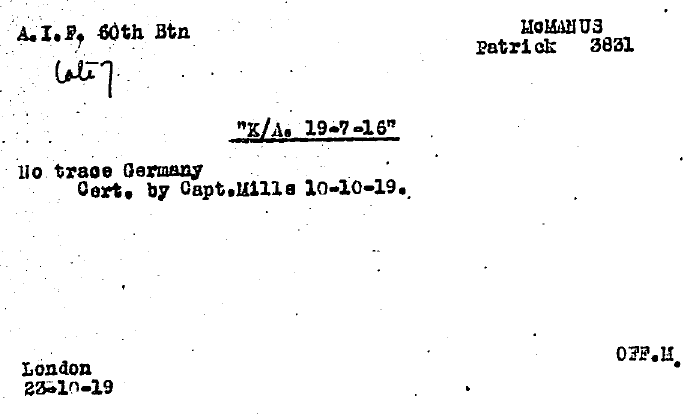

After the battle, Charles was pronounced “missing”, as many had reported him as wounded and/or dead. As Private Patrick Cloutt (1998) and Private John Bradford (3762) had stated:

“No bodies were brought in; he was never seen again.”

Capture

As the fighting came to an end, Mills and other prisoners were escorted along a communication trench to a farmhouse that was a collecting station for prisoners of war. A German medical officer took care of the walking wounded and Charles had his hand cleaned and bandaged.

As part of his interrogation by a German intelligence officer, Mills had to turn out the contents of his pockets, a photograph and a diary. The diary was of particular interest because it gave an account of the 31st Battalion’s activities since it arrived in France from Egypt just a few weeks earlier. The diary also contained a copy of the orders issued by British XI Corps headquarters that revealed to the Germans that the Fromelles attack was nothing more than a feint.

Despite knowing the British intent behind the attach, German commanders decided to keep its troops in the Lille area.

While the discovery of the orders had no bearing on German activities in the area, it shows that divulging operational information to the enemy, either willingly or unintentionally, was a reality of captivity in the First World War. Charles later confessed that it was ‘a serious error of judgement’ to allow such an important document to fall into their hands.

The material above was largely sourced from Aaron Pegram’s extensive research for his ANU thesis, “Surviving the War - Australian Prisoners on the Western Front 1916-18.

A Prisoner, but Already Supporting Finding the Missing

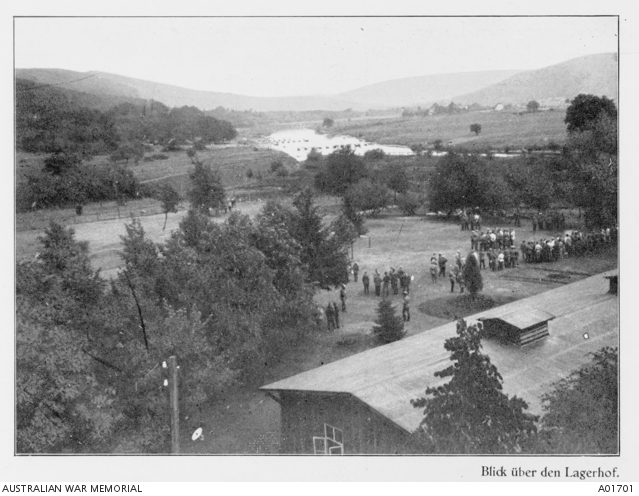

Six months after his capture, Charles was at a camp for Allied officers at Hannoversch Münden in Lower Saxony.

While here, he wrote to his commanding officer describing life as a prisoner of war:

‘Our daily life is much as we make it. Daily routine is in our own hands, and except for a roll call at 9.30 morning and night, we are left alone, which suits us very well’.

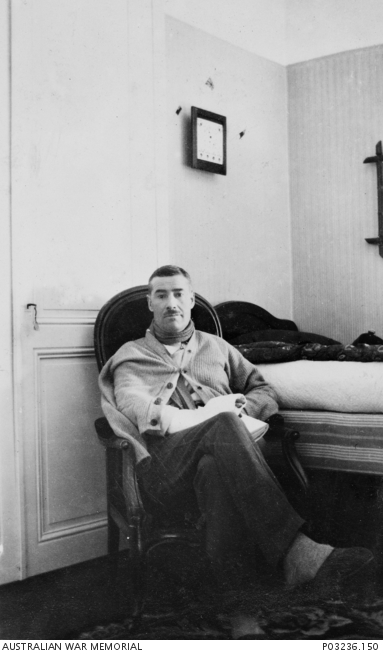

He spent his days in captivity reading, exercising, learning French and German, and enjoying walks beyond the prison walls. His captors were ‘uniformly courteous’ and the food was decent and better than expected. His greatest concern was the uncertainty of the war’s duration. ‘Time hangs! Day after day with absolutely nothing to do! I have led a busy and active life and find this enforced lack of occupation very trying’.

As result of his wounds, Charles was among the first Australians exchanged for internment, in Germany and Switzerland. To be transferred, the wounded had to have a disability that would negate their further military service or interned over 18 months.

He was able to have surgery on his hand and he wrote on 8 February 1918:

"I am writing with left hand. Right hand operated on last Thursday. All O.K. Stones and Wells getting on alright too."

Charles spent the remaining twelve months of the War in internment camps as the senior representative of approximately 100 interned Australians. During this time, he was dedicated to finding missing members of the AIF whose names appeared on prisoner of war lists from Berlin and relaying their whereabouts to London via the International Red Cross Office in Berne. This was the beginning of his Red Cross Wounded and Missing information exchanges.

After Armistice, he arrived in England on 11 January, 1919.

Charles’ Quest for the Missing Prisoners of War

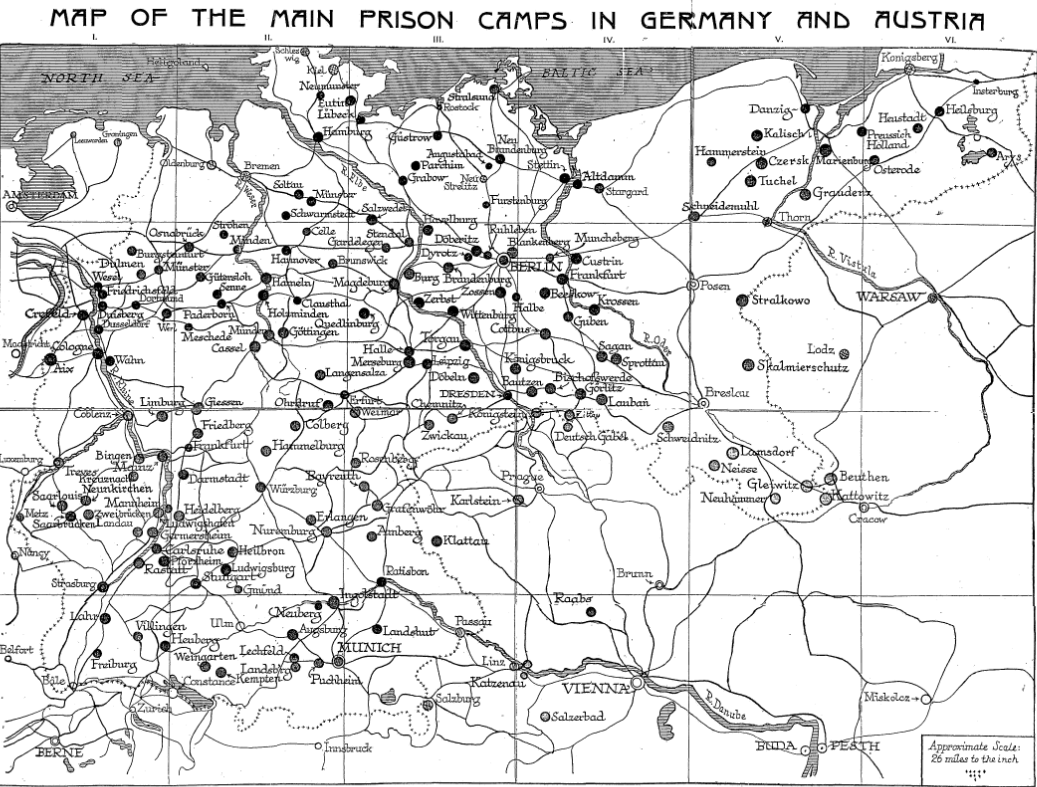

There were huge post-war efforts to locate the graves of missing Australian soldiers and prisoners. All told, there were 3,848 members of the AIF who surrendered to German forces in the fighting on the Western Front and all but 327 survived.

Source Aaron Pegram “Surviving the War - Australian Prisoners on the Western Front 1916-18”

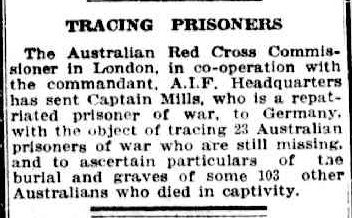

Instead of returning home, Charles stayed in Europe and was seconded to work with the Australian and International Red Cross to locate the missing Australian prisoners of war.

The Germans often had given a ‘soldier’s grave’ to Australian soldiers who had died in their custody. The graves were as well tended as those of the German soldiers:

‘engraved with the names and regiments of those who lay there, exactly in the same manner as the graves of each German soldier.’

However, the prison camps were spread all over Germany making Captain Mills’ task a daunting one.

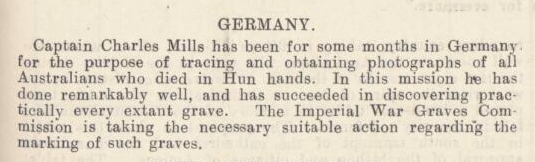

Accordingly, Charles then went back to Germany and spent months travelling across the country locating and photographing graves of Australians who had died as prisoners or were missing. His progress was often reported in the newspapers back home.

Incredibly, amidst all the turmoil caused by the war he found all but two of the Australian soldiers.

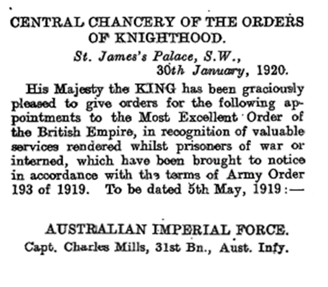

His quest complete, Charles finally came home to Australia in December 1919. His efforts were well recognized and, just after he returned to Australia, he was appointed to the Order of the British Empire.

Post War

Charles’ appointment with the AIF ended on 15 March 1920, but he rejoined the Royal Australian Engineers at Army Headquarters as the Area Officer of Tasman Area and Quartermaster of Citizen Force Units, Quartermaster/Hon Captain.

Charles also became a well-known lecturer on his experiences in Germany, once noting that:

“he believed their hopes of world dominion were far from shattered by their defeat.”

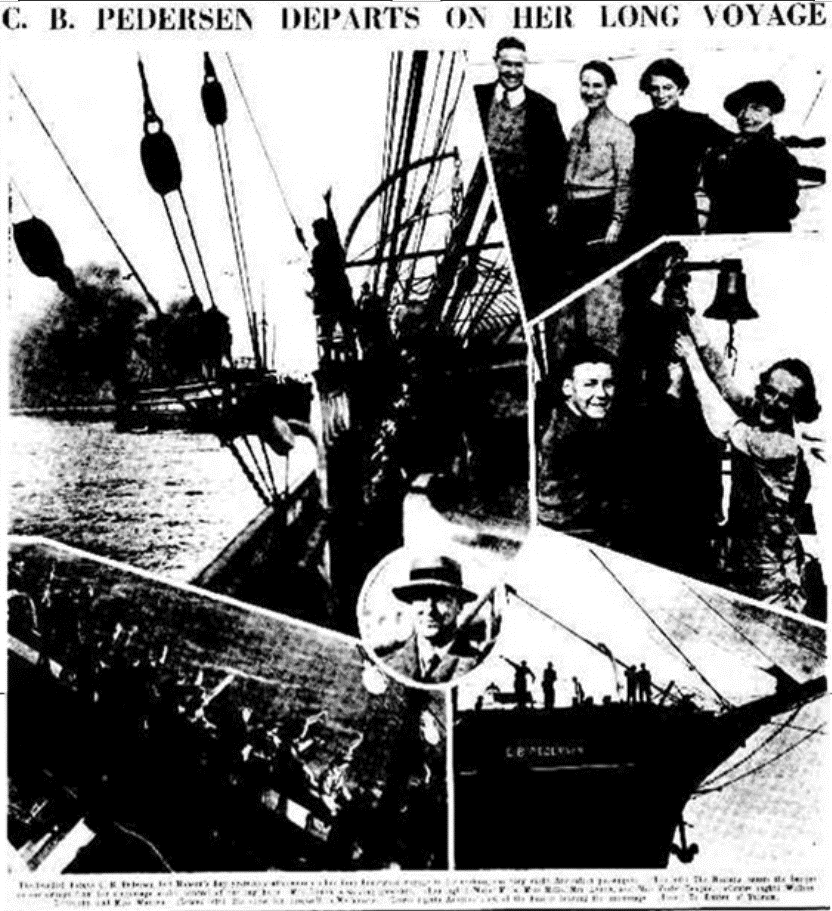

In his personal life, Charles suffered numerous tragedies. He lost his oldest son Alex in 1927, his wife Jessie in 1929 and his oldest daughter Florence in 1936, but he still had his youngest daughter, Glennie. Charles and Glennie shared a “dramatic voyage” between Australia and England in 1935 as two of the eight passengers on the barque C B Pedersen, one of the last few windjammers sailing that route. The C B Pedersen had held the record sailing speed from Australia to Britain for ten years.

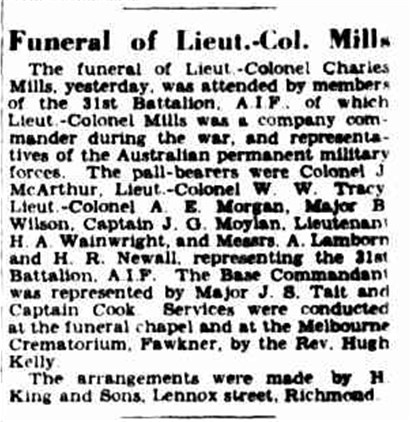

Charles passed away suddenly at the Epworth Hospital, Richmond VIC on 21 April 1937. He was 60 years old. His remains were cremated at the Fawkner Crematorium.

The 31st Battalion was out in force to honour him at his burial.

Captain Charles Mills – a career soldier truly dedicated to his mates.

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).