Extract from Paul Humphris Front Lines and Trenches 2019

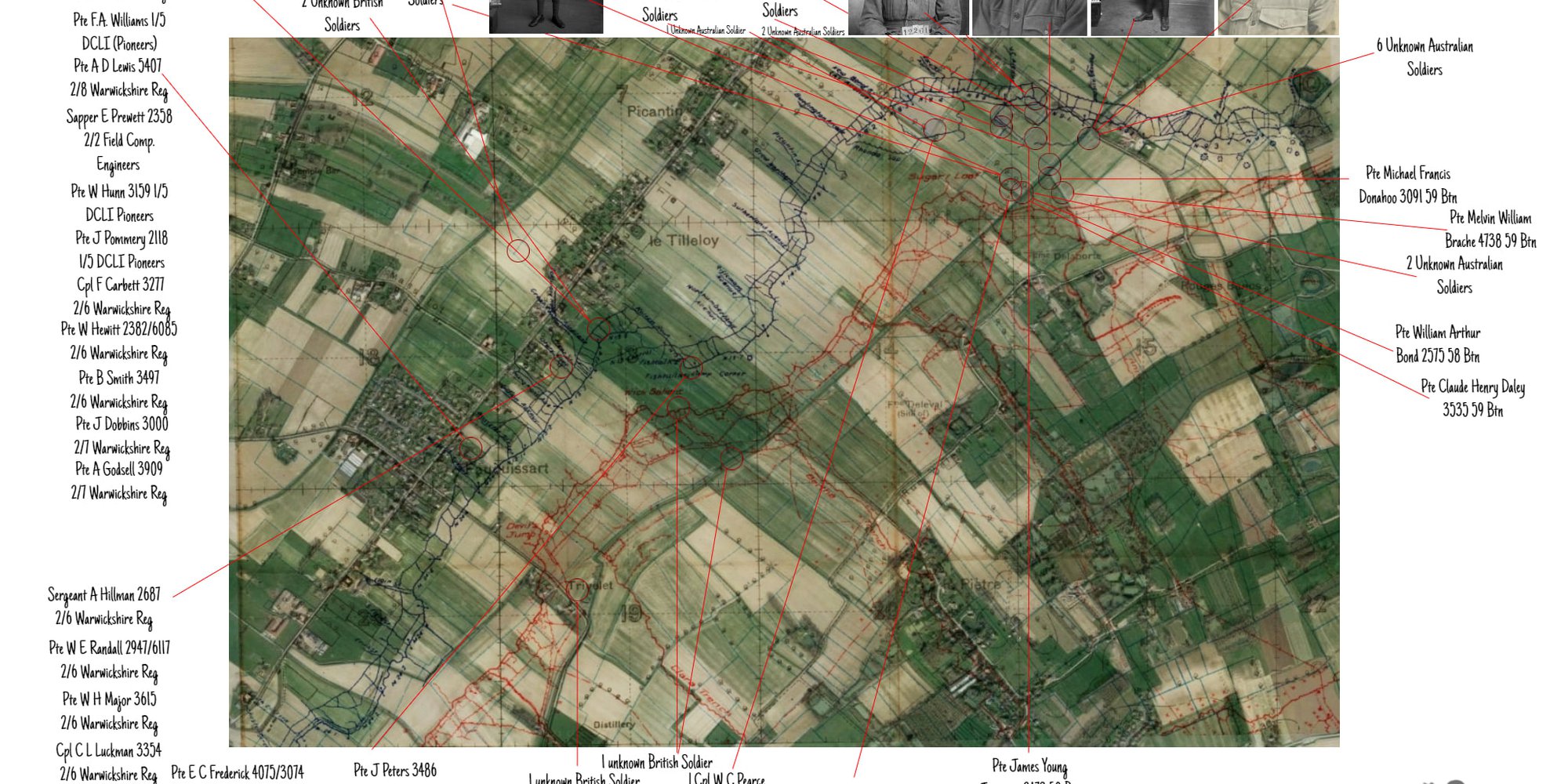

An overlay here showing the area of Pheasant Wood before and after the Fromelles battle of 19th/20th July 1916, together with related pictures and photos…

Some soldiers made it through into German lines, but were forced to withdraw back across No Man’s Land when support did not arrive. Those who had fallen close to, or in the German front-line were gathered up by the enemy, most probably transported by Light Rail and buried behind German lines in unmarked mass graves, including graves to the south of Pheasant Wood on the edge of Fromelles village. The graves went unrecognised for more than half a century until researchers, most notably retired Australian schoolteacher Lambis Englezos, identified them through historical research. When non-invasive survey and an evaluation confirmed their presence, the Australian and British governments announced a jointly funded programme of excavation and recovery so that the soldiers could be reburied in individual graves. With an international team of forensic and investigative professionals, Oxford Archaeology began excavating and recovering the soldiers in May 2009.

Unlike traditional archaeology, where the goal is largely scientific, this was a humanitarian project in which the sole focus was on the recovery and identification of individuals with living families using DNA. With just six months to complete the work, and under intense media scrutiny, innovative techniques were devised to meet the project’s unique requirements. A special site compound was designed to integrate the different elements – excavation, recovery, and analysis. The graves, eight of them in total, were excavated over a period of four months. Two were empty. Soil was meticulously removed, first by a small mechanical digger, and then using specialist hand-tools, to expose individuals (all practically skeletonised) and artefacts. Teeth and bones were sampled for DNA, and all evidence was comprehensively recorded before being lifted and transported to the temporary mortuary. The distribution of ages, artefacts, and types of peri-mortem trauma suggest that the soldiers had been buried alongside those with whom they had fought and had not been sorted by rank prior to burial. Groundsheets and cable were used to assist with moving and interring the bodies. It was suggested that the bodies had been buried, or the graves had been backfilled, between five and ten days after the battle had taken place. Each individual was examined one at a time.

Despite the wealth of documents, including letters, diaries, and photographs, that relate to the Battle of Fromelles, the artefacts and skeletons tell perhaps the most personal stories about what happened on the 19/20 July 1916. Many soldiers were in their teens, including at least two who were less than 18 years old – and therefore below the legal age of enlistment/conscription. The youngest was about 14 years old. There were also older individuals, aged up to at least 50 years, including at least two who were over the maximum age for enlistment/conscription. When the soldiers were buried, identity discs and personal effects were collected and sent back to the Red Cross and military intelligence, so it was expected that a limited range of artefacts would be found. However, about 5,900 artefacts were recovered and analysed for identification information with the assistance of radiography. Most of these items, both military and personal effects, were simply what the soldiers happened to be carrying with them when they were killed.

The majority were the remains of uniforms, such as badges, leather patches from mounted-style breeches, insignia, and buttons and equipment, such as webbing, gas masks, field dressing kits, and bayonet scabbards. Some boots were recovered but most were taken by the burial party: leather was in short supply and good boots would have been highly prized items. No steel helmets were found, probably because they were also salvaged or lost in the battle, but also, significantly, because they had not been issued to many of the Australian soldiers. Also, regulations stipulated that all soldiers were to be issued with two tags: one to stay with the body, the other to go to the Red Cross in the event of death in battle. However, most of the soldiers at Pheasant Wood seem to have been issued with just one dog-tag, which were diligently removed by the Germans when they buried them. (See note about identification discs below.)

All the recovered evidence was collated into confidential case-reports, one for each soldier, beginning in 2010, a data-analysis team collated this information with historical records, family trees, and DNA results from the deceased and their descendants. In July 2010, Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery was completed with the 250 Soldiers recovered from the Pheasant Wood pits reinterred. It was the first new war cemetery to be built by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in fifty years. To date 166 Australians have been identified.

(Taken from an article by Louise Loe)

Paul Humphriss, Fronts Lines & Trenches.