Lieutenant Colonel Ignatius Bertram Norris

“Here, I’m done, will someone take my papers?”

With the sound of unsuppressed machine gun fire whizzing through the air, cutting down more and more of his men that he had led into this nightmare…these are the last words spoken by Bertie Norris at around 6.30 pm on 19 July 1916, before he lay dead in No Man’s Land on the battle ground that was Fromelles.

Background

Ignatius Bertram (Bertie / Bert) Norris was the youngest son and one of eight children of well-known Sydney banker and honorary treasurer of St Mary’s Cathedral, Mr. Richard Augustine Norris (1843-1914) and Marianne (née Fennessy) Norris (1844-1915). Richard had been born in County Cork, Ireland in 1843 and immigrated with his parents to Australia. Richard had risen to be the manager of the south Sydney branch of the A.J. Stock Bank, which later became known as the Australian Bank of Commerce.

Bertie was born on 31 July 1880 into a devout Roman Catholic family. He was named for the Catholic Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order and, coincidentally, a patron saint of soldiers.

He was educated at St Ignatius College Riverview, Sydney. Bertie almost drowned during Riverview’s first ever swimming carnival, held in 1890, when he foolishly jumped into the pool, despite the fact he had never learned to swim! As he sank below the water, fellow student Charley Lennon jumped in and dragged him out, where he was then revived by Father Pigot, a Jesuit priest who had fortuitously been a medical doctor before joining the priesthood.

In 1896 Bertie passed his law matriculation and began his articles of clerkship at the offices of Messrs Brown and Beeby of Sydney, whilst at the same time reading for the bar. When he joined the NSW bar in 1908, he became the only person to be qualified as a solicitor and a barrister at the same time in NSW.

While he was just a slight man, only 168 cm and 63.5 kg, he was a keen sportsman and represented NSW in hockey. He was also decent tennis player, cricketer and golfer.

He was a member of the NSW militia. This organisation was founded in 1896 with the assistance of John Lane Mullins, a wealthy and well-connected man in Sydney, who turned out to be Bertie’s future father-in-law.

Bertie quickly rose through the ranks of the NSW Irish Rifles Regiment and was promoted to Captain in 1906. By the time the War broke out, Bertie was 34 years old and a Major in the 34th Regiment of the militia. He was also a prominent barrister with a thriving practice which included service as the Secretary to the Vice President of the NSW Legislative Council.

When the call to arms was sounded by the government of Australia looking for volunteers to join the AIF, Bertie responded, putting his duty above his personal life. He enlisted on 1 March 1915. Nine days later, he proposed to Elizabeth “Bessie” Mullins and they wed on 25 March 1915 in a military wedding at St Canice’s Church at Elizabeth Bay. The arrangements must have been made at a frantic pace!

All too soon, Bertie left for Egypt on 25 June 1915, with the rank of Major in the 1st Battalion, 5th Reinforcements. He boarded HMAT A40 Ceramic in Sydney and set sail.

Egypt

After arriving in Egypt, Bertie served with the 6th Infantry Training Division in Cairo. At that time there was no Army legal division, so officers were selected for court martial duty. With his legal background, Bertie soon found himself acting as the judge-advocate in courts martial.

Bertie’s personal life in Egypt would have been much brighter than your typical soldier, as newlywed, and pregnant, Bessie had left for Egypt shortly after Bertie arrived. While in Cairo, Bessie gave birth to their son, John Richard Bertram Norris on 18 February 1916.

Bertie could have stayed in the relative safety of Egypt, taking the safe option to serve out the War. However, he wanted to see some action. He had established a good reputation for himself as a leader and planner in Egypt and he managed to persuade his superiors to give him command of a battalion.

He was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel on 1 February 1916 and was appointed as the Commanding Officer of the 22nd Battalion. With the large influx of recruits from Australia to Egypt, there were numerous reorganizations underway and on 28 February 1916, he was reassigned to command the 53rd Battalion. With his reassignment, he left Cairo and his family for the camp at Tel el Kebir. The camp was a tent city which appeared out of the desert, some 9.5 kilometres in length and at its peak housing around 40,000 Australians.

Before the 53rd were to head to France, they still had work to do for the defence of the Suez Canal against Turkish attacks. In March, they were sent to Ferry Post on foot, a three-day trip of 57 kilometres over the soft sand of the desert in 38°C heat. Many of the men suffered heat stroke.

Orders to head to the Western Front were received in mid-June and they moved to the Moascar Isolation Camp to receive reinforcements. They transferred via train to Alexandria for embarkation onto the troop carriers that would take them to Europe. The 32 officers and 952 soldiers of the 53rd left Alexandria on 19 June 1916 on the Royal George and arrived in Marseille in late June 1916, the last of the four Australian divisions from Egypt.

After Bertie left for the battlefields of France, Bessie and baby John also left Egypt. They travelled to London to be closer to where Bertie was posted, in the hopes they would see him during his first leave.

The Western Front – Fromelles

After arriving in Marseille on June 28, they had a 62-hour train ride to Thiennes. The Battalion war diaries (AWM) noted that their ‘reputation had evidently preceded them’, as they were well received by the French at the towns all along the route. After several days marching the remaining 35 kilometres to Fleurbaix, they were settled into billets on 16 July by 0300.

They were moved straight into the front lines on the 17th, preparing for an attack, but it was cancelled by bad weather. They remained in the trenches on the 18th in relief of the 54th.

Bertie remained active in engaging with the soldiers. As documented in ANZAC Biographies, ANZAC stories from the Maryborough Military & Colonial Museum, Queensland, Fr Kennedy’s book The Whale Oil Guards (1919, page 50) gives details of Lt Col. Bert Norris’ service in France:

“Bert was liked by his men. Several times a day he would visit them, always with a smile on his face. His men were his chief care.”

“On the night before the battle, exhausted, Bert called for Father Kennedy and after discussing a number of issues and concerns, he told Father Kennedy, ‘I feel almost convinced that tomorrow will witness my first and last fight. Strange to say, the thought does not worry me, until I think of Bessie and my child. My God, if ever a man was blessed with a perfect wife, I am. Perhaps we are too happy. Should anything happen me! I mean should the worst befall, will you write to her?’“

“Father Kennedy replied, ‘Nonsense, Colonel. Put the silly thought out of your head. The battalion is bound to do great things tomorrow.’”

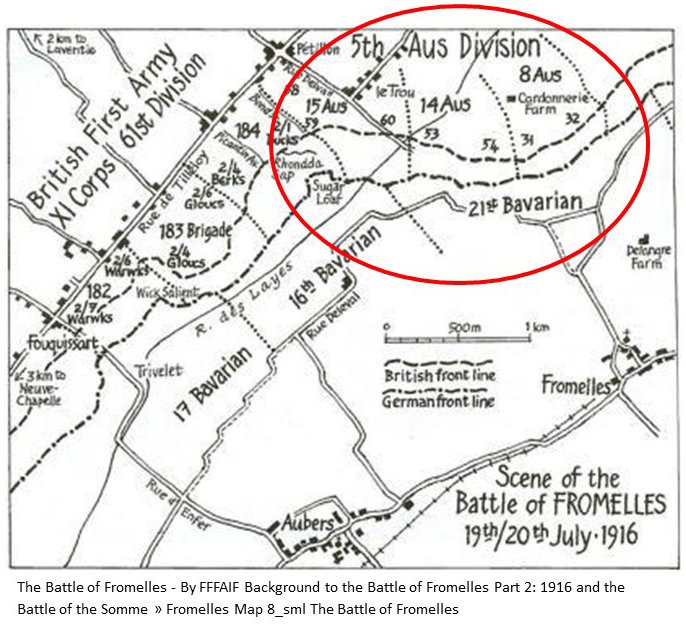

On 19 July, Bertie received his orders from Captain Geoffrey Street, who he probably knew from Sydney, as Geoffrey was the nephew of Justice Street, a judge in the Supreme Court of New South Wales. Bertie and the 53rd would be attacking in the centre of the Australian forces, with the British troops on their right.

Bertie was to lead his men into their first major battle and HIS own first battle, an impossible 400 metre dash across open fields guarded by the “Sugar Loaf” – an elevated concrete bastion protected by a myriad of machine guns trained on the open ground.

By 11.00am on the 19th, heavy bombardment was underway from both armies.

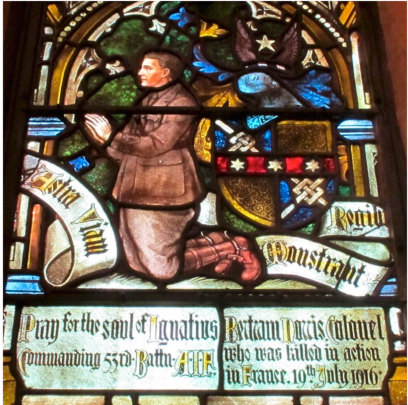

No doubt the men were nervous, but excited and probably scared. Before the battle Bertie knelt before the Battalion padre, Father John Kennedy, and received Holy Communion, his faith never wavering.

At 4.00pm the 54th Battalion rejoined the 53rd on their left and all were now in position and prepared for an attack.

The Australians went on the offensive at 5.43pm. There were four waves from the 53rd, half of A and D Companies in each of the first two waves and half of C and D in the third and fourth. Bertie went over with the fourth wave.

The first waves did not immediately charge from the Australian line, but went out into No Man’s Land and laid down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift.

At 6.00pm, the Germans were rushed, their front line captured and the Australians headed for the second line.

Bertie kept to the lead calling out in encouragement to his men, “Come on lads! Only another trench to take!” However, a few short steps later he was hit several times with the unrelenting machine-gun fire from the enemy lines. As he sunk to the ground he called out “Here, I’m done, will someone take my papers” , and then he was gone - within the initial 20 minutes of the battle.

As his spoke his final words, his Adjutant, Lieutenant Harry Moffitt, turned and ran back to him, joining Private Frank Leslie Croft in attempting to bring Bertie back to their own lines. Sadly, Lieutenant Moffit was killed by machine-gun fire moments after reaching Bertie. It is reported that Harry fell dead across his commanding officer’s body.

The 53rd succeeded in taking the German first and second line trenches, linking up with the 54th on their left, but no support came from the right, which was directly across from the heavily defended machine-gun emplacement at the Sugar Loaf salient.

By 9.00am on the 20th, the 53rd received orders to retreat from positions won and by 9.30am they had ‘retired with very heavy loss’. Of the 984 men who had left Alexandria just weeks ago, 372 were killed or missing and 335 were wounded. By 4.30pm the remains of the Brigade assembled at HQ.

While the initial reports from the battlefield indicated that Bertie’s body was being carried out of No Man’s Land, this was incorrect. His body and ID tag were later recovered by the Germans.

Lieutenant Colonel Ignatius Bertram Norris was the highest ranking officer to be killed in the Battle of Fromelles.

Captain Geoffrey Street later reported that he and Bertie’s own men could testify to Lt. Col. Norris’ personal courage and leadership, both of which were gallant, in the extreme. Bertie’s men respected him, calling him a “man in a million” , commenting that he spoke to them almost as an equal, and he was so “nice and friendly”.

The Aftermath for Bessie

Bessie, waiting in London, heard of Bertie’s death about a week later, from both formal channels and from letters from Bertie’s comrades which included the Battalion padre, Father John Kennedy, perhaps receiving some comfort from his devotion to his faith and by the high regard in which his men held him.

By early October 1916, Bessie had been forwarded Bertie’s brown army kitbag containing his copy of the New Testament, a set of dominoes, a dictionary, his rosary beads, a spirit flask, and his wallet containing photos of Bessie and baby John.

Despite her loss and grief Bessie did not return to Australia immediately. What was the point? Her Bertie lay in a field in France. She would be closer to him in London. So, she and little John stayed.

Bessie and John eventually returned home to Sydney, returning to her childhood home of Killountain. For the rest of her long life, Bessie (1888-1975) considered herself a widow of Bertie Norris – never remarrying.

Bertie’s son, John Richard Bertram Norris followed in his father’s footsteps, attending Riverview College and establishing a career in law. John also served his country in World War 2, enlisting in the 2/17 Battalion (2nd AIF) and saw active service in Tobruk and Alamein. He died in 1994, aged 78 years.

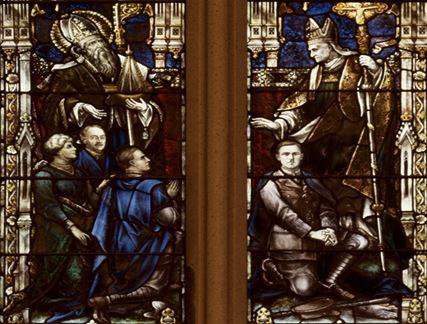

The family has commemorated Bertie and Bessie’s brother, 2nd Lieutenant Brendan Lane Mullins, in three stained glass windows: the Norris Memorial Window at the base of the south-west tower in St Mary’s Cathedral, in Saint Canice Church and in the St Ignatius College Chapel, Riverview. Bertie’s name was also used for many decades for the senior debating prize – the Bert Norris Gold Medal - awarded each year by Riverview College.

Bertie is also remembered on Panel 157 of the Australian War Memorial; Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery; Saint Ignatius’ College Riverview on the Honour Roll and in the Dalton Memorial Chapel; and on the New South Wales Solicitors’ Honour Roll.

Final Closure, 94 Years in Coming

Despite the efforts of his men, Bertie’s body was not recovered by the Australians. His body and ID tag had been recovered by the Germans, but no further information was available.

However, in 2008 a mass grave that had been dug by the Germans outside Fromelles was discovered. It contained the remains of some 250 soldiers. An Australian Defence Force project worked to match up DNA of the soldiers in the grave with living relatives in order to identify and honour the soldiers properly.

On Wednesday 7 July 2010, Bertie’s remains were among those positively identified.

Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery

He has now been given a proper burial and is interred at the Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery, Plot III, Row A, Grave No 3. Unfortunately, neither his loving wife Bessie nor his son John lived to see this.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Foremost, thanks go to Mr. Bayne “Gus” Kelly, great nephew of Bertie and Bessie who kindly spoke with me several times, filling in some gaps and providing new directions.

Thanks must also go to Mr. John Meyers and the Maryborough Military & Colonial Museum for being the custodian of Bertie’s medals, and always available to try and answer my questions.

Finally, I am indebted to two works on the battle of Fromelles. Both Patrick Lindsay’s work Our Darkest Day (EISBN 9 781 742 736 648) and Peter Barton’s book The Lost Legions of Fromelles (ISBN 978-1-47211-712-0) are invaluable sources to anyone interested in this moment in time and I highly recommend them.

And to Bertie and Bessie Norris – thank you for allowing me into your past. I hope you have found each other again.

Natasha Heap

Links to other sources