Guy Somerville Dion GIBNEY

Eyes blue, Hair dark, Complexion medium

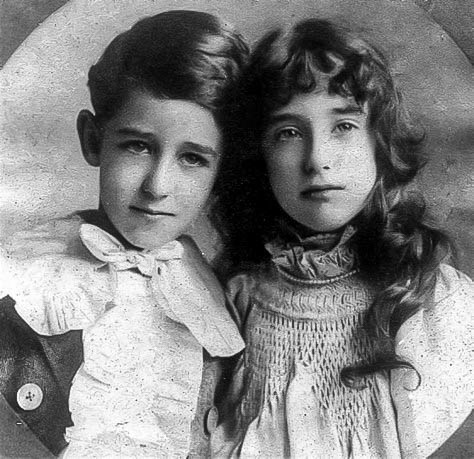

Guy and Iris Gibney – Resilient Twins

Can you help us identify Guy?

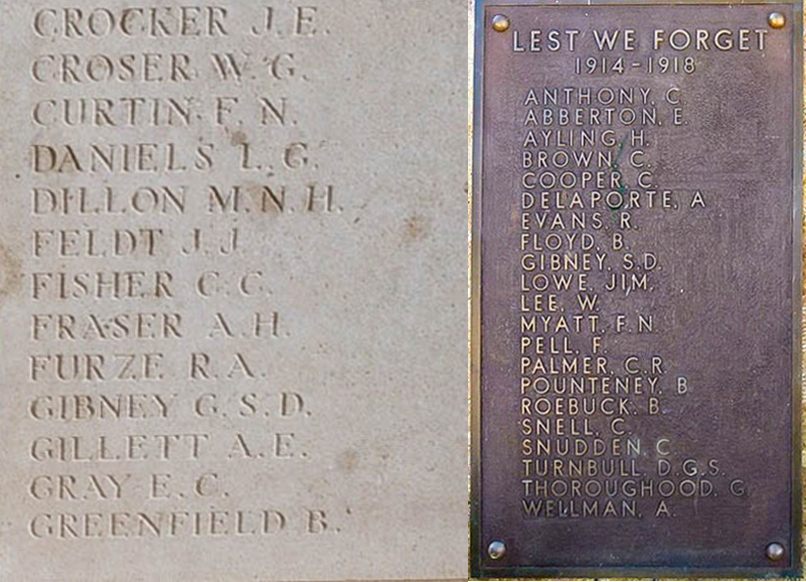

Guy was killed in Action at Fromelles. As part of the 32nd Battalion he was positioned near where the Germans collected soldiers who were later buried at Pheasant Wood. There is a chance he might be identified, but we need help. We are still searching for suitable family DNA donors.

In 2008 a mass grave was found at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 (Australian) bodies they recovered after the battle.

If you know anything of contacts here in Australia or his relatives from England and Ireland, please contact the Fromelles Association.

We would like to thank Mairéad Crinion for her exhaustive research and insights from her genealogical, family history/memoirs and battle details and text which are incorporated into this story. Her full documentation was published in 2017 in Navan Co. Meath, Ireland in the Navan & District Historical Society’s Journal - Navan - Its People and Its Past, Vol. 4, GUY – The Search for Guy Somerville Dion Gibney, pages 182-219. Excerpts are here, reproduced with their kind permission.

Also thanks to Wayne Garwood, Iris’s Grandson, for her memoirs, Guy Palmer, Guy’s Nephew, for the family photos and to Iris’s great granddaughter Tara for her contributions.

A Very Unsettled Life

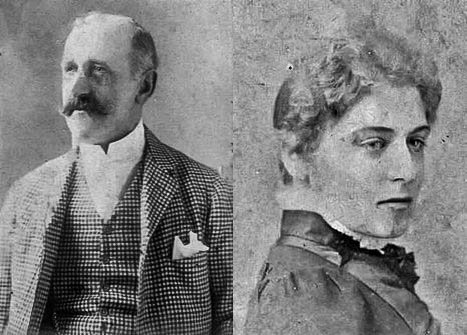

Twins Guy Somerville Dion Gibney and Iris Tara Gibney were born on 3 March, 1894. They were both baptised in St. Stephens’s Church Paddington, London, on 17 April 1894. Their parents were Edward Somerville Gibney and Fanny Elizabeth Maud Gibney (nee Bartlett).

Edward was a Journalist at this time. He made his living working as a proofreader for publishers and had articles published himself in such publications of the day as Punch. Their mother Fanny was an unusual woman to say the least. She was reputed to be quite a rare beauty and may at some time have worked as an actress. She seemingly put off her marriage to Edward as she didn’t wish to have any children. Nonetheless he persevered and they were married 12 July 1892.

Regardless of Fanny Bartlett’s wishes, two years later she had twins. She immediately abandoned them for reasons unknown, possibly it may have been a form of post-natal depression, but she had nothing more to do with them. The whole of their childhood was unsettled. Guy and Iris were sent away to live with and be reared by a ‘nurse’.

This ‘nurse’ was reported to the authorities for cruelty to them by her own neighbours and the twins were collected by their father. He then brought them to live with his mother and his first cousin ‘Aunt Lucy’ Green. Lucy was already a carer for her Aunt/Iris and the twins’ grandmother Mary. In 1901 they were living in a boarding house in Brighton, where Iris remembers they ‘lived in one room together’. Mary passed away in 1905.

Eventually their father decided that he could no longer afford to pay his cousin to mind the children, and they were sent to live in yet another home, in Dover, with a widow and her sister who was described as being ‘unbalanced’. The children had a dismal existence there and were very miserable and lonely for their Aunt, who had been so motherly to them. It would appear that their time there was indeed wretched as Iris was later to find a letter in her father’s papers saying “the doctor said [that] Iris’s ulcers on her hands [were] caused by semi-starvation.”

This information got back to their father and their lives finally took a positive turn. Edward and their mother’s married sister, Zem Parsons, arranged for Guy and Iris to live with an ex-governess of her own children. She was married to the Rev. Wadeson, living in Bramham Moor, Yorkshire.

The Wadesons had a daughter Inez and a son Edward and a governess, Miss Osborn, who became dearly loved. Iris states that it was the happiest time of their lives together, ‘a time full of love and care’. Eventually time came for Inez and Edward to go to boarding schools and change and uncertainty crept into their lives again. The twins’ father was unable to cover these costs and a message arrived to say he was sending them off, again, to a children’s home, run by a relative, in Canada.

The Wadeson family / guardians were very upset by this and wrote to complain to their father and the Aunts. Their mother’s sisters stepped in and took the twins and passed them between themselves at different times, so much so their parents had no idea where the children were - it seems they were trying to hide them from their parents.

‘While we were at Uncle Jack Bartlett’s, a letter came to me from my father asking for my address, and, always having to obey who we were staying with, I took it to my Uncle who said he would answer it. Eventually they came to an agreement that we should be handed over to my father on condition that we went to Mr. and Mrs. Collard at a place called Wigan.

I really think they were forced to, as I heard my father had a detective looking for us. Finally one day a cousin took us to London and we met our father at the railway station and Mrs. Green (or Aunt Lucy) was there. Poor dear wanted us to tell her where we were being sent, but we did not know.

We were put into a carriage and just before the train left my father told us we were going to be met by Mr Collard at a place called Wigan. Just as Aunt Lucy kissed us goodbye we were able to whisper it to her, poor dear. We were all crying, frightened, travelling alone to complete strangers.’

Not long afterwards, another letter arrived from their father asking Mr Collard to take them both to Dover and put them on a boat, as they were to go to school in Switzerland and stay with the Werner family. Mrs Werner was an English woman married to an Austrian banker. They attended a good secondary school there and Iris remembers very fondly walking in the area and in the wider Alps. They were well treated by the family. Eventually, the inevitable letter arrived from their father saying he had decided to send them to Australia to stay with Mrs Myatt, a cousin of their current guardian, Mrs Werner. Mrs Myatt would be paid £200 each to rear the children to the age of 21 years.

Iris did recall, just once ever, seeing and going to tea with her mother. There were biscuits, and Iris asked for one. Her mother replied, ‘those who ask for things, get nothing.’ She was not allowed one and never saw her mother again. Their father sometimes visited ‘on the quiet’ not telling his wife he was doing so. So, before either of their parents had died, Guy and Iris Tara Gibney were sent to Australia at the ages of just 15 years in 1909. They were put on the night train for Marseilles and their father met them at the boat.

He gave them a supply of clothes and made them promise faithfully not to write to anyone they had known saying ‘no Englishman or woman ever broke a promise’. Obeying their father, they were effectively cut off from all family and friends. On his return from saying goodbye to his children Edward Gibney, their father, had his first heart attack. This was the first of several heart attacks which ended his life in 1911. His wife Fanny lived until 1946.

Life Turns Around in Australia

Guy and Iris arrived in Fremantle, Western Australia on 7 July 1909, aged 15 years and 4 months old. They settled in with the Myatt family in Harvey, Wellington, Western Australia. Mr and Mrs Myatt had a son Frank, to whom Iris would later become engaged, a daughter Madeline and two younger sons, Tom and Martin. Their new Australian family had a typical Australian wooden farmhouse with a lovely wide veranda and the Myatts had used some of the monies sent to look after them to build on a bedroom each for them. Life was fun with the Myatts. Iris recalls going to dances and playing tennis. She went out to work at this stage of her life, working in domestic service duties in a couple of local houses.

Guy began working as an orchardist (oranges). Iris and Guy enjoyed themselves in their new life. They had good friends and enjoyed a normal teenage existence there. Iris became engaged to Frank Myatt when she was 17 years old, but they didn’t have the money to get married. Not long after Iris become engaged, a policeman turned up at the Myatts with the news of their father’s death. After all they had been put through by their parents, it must have been ‘liberating’.

Iris wrote in her memoirs:

“It transpired that one day Mrs. Green (Aunt Lucy), who had looked after us, was in the room by herself when my father was dying and she saw a new address book open by his bed and it had an Australian address in.

Something struck her to copy it and she gave it to her good friend Mrs Valance. Mrs Valance owned half of Hove (Brighton), and Mrs Green had been her bridesmaid. They both had the idea that the address was where we might be, although they had thought we might have been ‘done away with’.”

This was investigated by the police. Iris would later be told that just before he died, “my father said ‘God Bless the children’ in the hearing of Aunt Lucy, but my mother said he was speaking of the kiddies next door.” She went on to say – “After my father’s death I felt my promise (to not contact anyone) was not binding, so I wrote to everyone, but sad to say most of them died not so long after. It hurt the Aunts Fletcher and Parsons. Mrs Wadeson died of cancer, but I kept in touch with Inez by then living in New Zealand.” Iris and Guy had a small party for their 21st birthday in March 1915.

Off to War

Not too long after their party, Guy signed up to join the Army (he had to try to enlist four times as he was too narrow in the chest). He enlisted along with his Iris’s fiancé Frank and lots of other friends. As noted in Iris’ memoirs, “It was a sad day for us all in November, but one could not grudge the boys, and Guy was so thrilled as all his friends had joined up too.” Guy was assigned to the 32nd Battalion C Company and Frank to the 11th Battalion. The 32nd Battalion was formed at Mitcham, South Australia on 9 August 1915. A and B Companies were to be from South Australia while C and D from Western Australia.

The men from WA arrived in Adelaide at the end of August and training for all continued there until they departed for Egypt on 18 November 1915 on the troop ship HMAT A2 Geelong.

As reported in The Adelaide Register:

“The 32nd Battalion went away with the determination to uphold the newborn prestige of Australian troops, and they were accorded a farewell which reflected the assurance of South Australians that that resolve would be realized.”

Egypt

Guy arrived in Suez on 14 December 1915 and was moved to El Ferdan just before Christmas. A month later they marched to Ismailia, then to Tel el Kebir for February and most of March. The next stops were at Duntroon Plateau and Ferry Post until the end of May, training and guarding the Suez Canal. Their last posting in Egypt was a few weeks at Moascar. One soldier’s diary complained of being “sick up to the neck of heat and flies”, of the scarcity of water during their long marches through the sand and he described some of the food as “dog biscuits and bully beef”.

He did go on to mention good times as well with swims, mail from home, visiting the local sights and the like. Source AWM C2081789 Diary of Theodor Milton PFLAUM 1915-16, page 29, page 12]] You can read Theodor’s Soldier Story here

During their time in Egypt the 32nd had the honour of being inspected by H.R.H. Prince of Wales.

To the Western Front

After spending six months in Egypt, the call to support the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front came in mid-June. They left from Alexandria on the ship Transylvania on 17 June 1916 and arrived at Marseilles, France on 23 June 1916. They then had a two-day train trip to Steenbecque. Their route took them to a station just out of Paris, within sight of the Eiffel Tower, through Bologne and Calais, with a view of the Channel, before they disembarked and marched to their camp at Morbecque, about 30 kilometres from Fleurbaix.

Theodor Pflaum (No. 327) wrote about the trip in his diary:

“The people flocked out all along the line and cheered us as though we had the Kaiser as prisoner on board!!”

Training continued with a focus on bayonets and the use of gas masks, assuredly with a greater emphasis given their position near the front.

Fromelles

The 32nd moved to the front on 14 July and Guy was into the trenches for the first time on 16 July, only three weeks after arriving in France.

On the 17th they were reconnoitering the trenches and cutting passages through the wires, preparing for an attack, but it was delayed due to the weather. D Company’s Lieutenant Sam Mills’ letters home were optimistic for the coming battle:

“We are not doing much work now, just enough to keep us fit—mostly route marching and helmet drill. We have our gas helmets and steel helmets, so we are prepared for anything. They are both very good, so a man is pretty safe.”

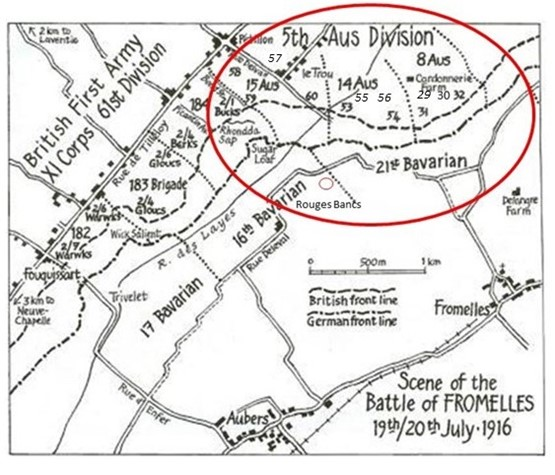

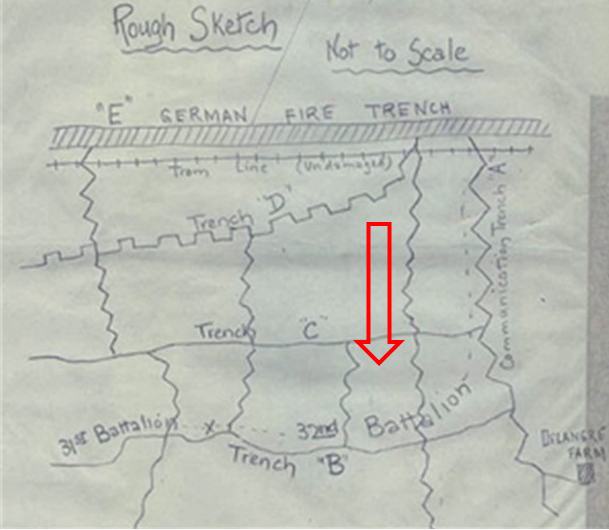

The overall plan was to use Brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault of the German trenches at Fromelles. The 32nd Battalion’s position was on the left flank, with only 100 metres of no man’s land to get the German trenches. As they advanced they were to link up with the 31st Battalion on their right. However, their position on the extreme left flank made their job more difficult, as not only did they have to protect themselves while advancing, but they also had to block off the Germans on their left, to stop them from coming around behind them.

On the morning of the 18th, A Company and Guy’s C Company went back into the trenches to relieve B and D Companies. B and D rejoined on the 19th. All were in position by 5.45 PM and the charge over the parapet began at 5.53 PM. Guy’s C Company and A Company were the first and second waves to go, B & D the third and fourth. They were successful in the initial assaults and by 6.30 PM were in control of the German’s 1st line system (map Trench B), which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

Source AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

Unfortunately, with the success of their attack, ‘friendly’ artillery fire caused a large number of casualties. They were able to take out a German machine gun in their early advances, but were being “seriously enfiladed” from their left flank.

By 8.30 PM their left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and the 32nd was told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

Fighting continued through the night. Up ahead, the Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine gun fire from behind and from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map). Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers of the 32nd.

At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance they could offer was with rifles - “The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

Source AWM4 23/48/12, 31st Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 29

Guy was killed during the 32nd’s retreat. His mate, Les Western (334), gave detailed description in January 1917 of what happened to Guy:

“On retiring from the German trenches in the Fromelles region on the morning of July 20 1916 Pte. Gibney and myself passed over the German front line together and we just exchanged the usual greetings ‘Good-day’, although it was a rotten day, by the way.

When about in the middle of ‘no man’s land’ I got a bullet, so dropped into a shell hole and went to sleep for about five hours. When I woke at what I judged to be about 9 AM I heard someone calling in agonised tones ‘For God’s sake give me some water!’ On looking along the water gutter leading to the shell hole I saw my friend Guy Gibney and another fellow (Pte. C. J. Judge (971)), so having about a half dozen mouthfuls of water in my bottle, I crawled to them and gave them a sip each, at least shared it between them.

Gibney was badly wounded in the upper part of the legs and chest by shrapnel… After I gave them the water, barely more than two mouthfuls each they became quiet and to a casual onlooker apparently asleep, but I regret to say they succumbed to their wounds.”

A number of other witnesses gave similar reports. The wounded Les Western did manage to somehow finally crawl back to the Australian lines the night of the 21st, 18 hours after he had been shot. He survived the rest of the War and returned to Australia in 1919. The initial roll call count for the 32nd was devastating – 71 killed, 375 wounded and 219 missing. The final impact was that 225 soldiers of the 32nd Battalion were killed or died from wounds sustained at the battle and, of this, 166 were unidentified. Lieutenant Sam Mills survived the battle. In his letters home, he recalls the bravery of the men:

“They came over the parapet like racehorses……… However, a man could ask nothing better, if he had to go, than to go in a charge like that, and they certainly did their job like heroes."

Iris – her personal trials continued

News of the battle was broadcast back home and Iris not only had to worry about her brother, she also had to worry about her fiancé, Frank, who was fighting at Pozieres at the same time. He was with the 3rd Infantry Brigade Machine Gun Company.

“We waited for news and one day the Clergyman came with a wire, saying Frank had been buried by a shell. An hour after, Win Gibbs came out with a letter from Les Weston, telling her about the attack, and saying that Guy also must have staggered out into No Mans Land in desperation, as that night Les had heard someone calling for water from a shell-hole. He crawled down and found Guy and gave him a drink of water, which is no good for a stomach wound. Guy asked him to write to Win and said that if he did not rcover that his last thoughts were of her, and he never spoke again. Les was picked up, but Guy was never found.

It could hardly get any worse. Frank was formally declared as killed in action on 27 August 1916, but the declaration for Guy did not occur until 20 April 1917. Iris was now left alone, without her twin brother and constant companion and with her hopes and dreams of her marriage lost too. Having been through such a difficult life with Guy, this proved too much for Iris. It took her a number of years to recover from the shock. Later, she went to work for a very nice couple, the Palmers.

As they lived by the sea, Mrs Myatt thought the change of air and scenery would be of help to Iris. Iris and another girl were housekeepers and carers and looked after the Palmer’s two small children. Sadly, however, Mrs Palmer was dying of cancer and even more so, Iris went home for a while to nurse an ill Mrs Myatt who died from heart trouble in Iris’s arms. Mrs Palmer also did pass on. While it was a tragic sequence of events, over a year later Geoffrey Palmer proposed to Iris, in line with his wife’s wishes.

Once his children had given their consent, which was a condition of Iris’s, they married on 28 April 1923.

Iris went on to have four children of her own - June Tara, Guy, Edward and David. After a long illness with breast cancer, Iris Tara Gibney Palmer died in January 1966 aged 72 years. Her husband Geoffrey survived her by only 6 months. He was 92. Iris was a brave, courageous and resilient person, surviving numerous personal trials that continued throughout her and Guy’s lives. Someone to be admired.

Gone, but not forgotten

Guy’s great Great Niece Tara, named after her great grandmother, is well aware of Guy’s sacrifice. She and her husband Tim visited Fromelles on 9 July 2011 and were very moved by the experience.

Tara wrote:

“The dreadful night of Fromelles saw Iris Tara lose her twin brother and her fiancé. Both never came home, were never properly buried and Iris never got to say a true goodbye to the two people that meant the most to her.”

“When you hear a story like that, it becomes a personal tragedy. But just think of the other 5531 Australians killed that night; they all had stories like this, and that is a national tragedy. This is why we felt compelled to visit the memorial cemetery erected at Fromelles.

As I walked the graveyard, I thought of my great uncle and then of my great grandmother Iris. How she lost her twin brother and fiancé all in that one dreadful night. The saddest thought struck me, that in another time or place that could have been me, I could have lost my Husband Tim and my brother Simon that night, my two best friends…gone…never to come back.

What did make me smile however, was that the memorial is so nicely surrounded by lush green paddocks filled with trees and loads of dairy cows. It was just like the dairy farm that my past generation of family came from, lived and worked on. It was the same type of land that my family home still stands on. As Guy and Frank lay to rest nearby, I know that they rest in peace with reminders of home and cared ones, when they are actually thousands of miles away.”

Her husband Tim said:

“…what these people died for was important - defending their way of life. Because of them I have the freedom to go down the beach on a sunny day and enjoy a surf, or freedom to play a game of footy, or own a dog, the freedom to vote or the freedom not to.”

Lest we forget. As of 2024, 41 of the 166 originally unidentified soldiers from the 32nd have been confirmed to be in the German mass grave at Pheasant Wood that was found in 2008. These soldiers have now been given a proper burial and recognition. There are a further 70 soldiers from 250 who were in the grave that are not yet identified. One of them could be Guy. With Les Weston’s witness statement, Guy may have been too close to the Australian lines to have been recovered by the Germans and they did not report as having found his ID tag, but without DNA samples, we will never know.

Mairéad Crinion writes of her genealogical research:

“At very long last, the only people who carry the name and the Y-DNA of the Gibney’s of Navan Co. Meath and of Guy Somerville Dion Gibney who died at the Battle of Fromelles have been found. Ironically, the story has come full circle with Guy’s only living male relatives being found.”

“I hope one day to go along and pay my respects to him (Guy) in France and thank him

for the satisfaction of ‘doing’ his family tree and taking a trip across time and place

with him and his extended family from Navan Co. Meath to so many parts of the world.”

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).