In mid-August, Gordon’s family were notified of him being listed as ‘missing’ but no further details were available.

In October 1916, the family’s hopes were raised that he’d been taken prisoner when they received a cable to the effect ‘All well’ and signed ‘Starr’. They were at a loss to know which son had sent it. Also, Richard Starr, cousin of Gordon who was serving in Palestine, mentioned in a letter to his mother that his Aunt Harriett kept writing and asking him if he had seen Gordon. He added, ‘She can’t know he is missing’.

In July 1917, a court of enquiry was convened in France and after hearing witness statements now contained in the Red Cross files, it was determined that Private William Gordon Starr, 1291, died 20th July 1916.

Thirteen months after his death, the family were notified and again it was the local press that gave more details though it stated incorrectly that he was invalided in England when his record shows he convalesced in Montasah, Egypt after his bout of bronchitis.

Correspondence between the family and the military continued for another five years and it is evident that this was an emotional drain on Gordon’s mother. As nominated next of kin Hannah was granted a pension of £2 per fortnight dating from 15 October 1916.

Hannah requested a copy of her son’s death certificate. Base Records responded with a ‘certificate of report of death’ which confirmed the details of the court of enquiry but gave no particulars relating to his burial.

The next correspondence Hannah Starr received was July 1920. This was a generic Form A, requesting particulars for the inscriptions for War Graves, The Nation’s History and Roll of Honour. Hannah’s response on the bottom of the form was that of a heartbroken mother:

“Sir, I do not wish to have any thing to do with this form. My son was reported to me by the military as missing from 23 July 1916, then reported Killed in Action and I have heard nothing further from the military and so far as I know His (sic) body was not found. I received nothing belonging to him.”

NAA B2455, STARR, William Gordon, page 20

With the passing of time Gordon’s mother again wrote to Base Records in July 1922 that she had still not received the plaque. It was finally despatched and the plaque, known as the ‘dead man’s penny’, is held by family members along with the General Service Medal that was issued to his father.

The Gallipoli Campaign Medal which was awarded in 1967 and to which Gordon was entitled was not claimed until a family researcher made family members aware of it in 1992. This medal was sold on Ebay about 2015 and a chance discovery of it listed again for sale two years later brought it back into the Starr family.

In June 2008, Lorraine and John Hodgkins, toured the Western Front battlefields where Lorraine’s father, Walter Leonard Starr, cousin of William Gordon Starr, joined the 54th Battalion about three months after the battle of Fromelles. The Hodgkins visited Fromelles on 6th June and chanced to meet Australian Army personnel - historian Roger Lee and Major General Mike Woods - who were engaged in the Pheasant Wood excavations at Fromelles.

Roger Lee stood with the Hodgkins on the rise overlooking the site and pointed out the landmarks relating to the battle. He was adamant that there were no Australian Diggers buried at Pheasant Wood, only British. Two days later the Australian rising sun badge was unearthed by the archaeologists proving Australian men were buried there.

William Gordon Starr was one of seven grandsons of Mrs Betsy Starr of Molong who enlisted. He was the only one not to survive the war and his body was not found. Following the 2008 discovery and excavation of the German burial plots at Pheasant Wood, relatives whose DNA may prove that one of the Diggers buried there is William Gordon Starr are awaiting the results of the samples submitted in late 2019.

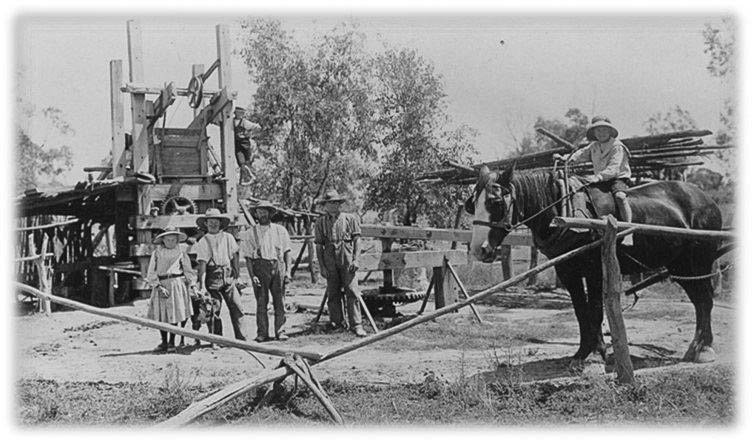

Gordon’s parents would have dearly loved to know where their son was buried but that was not to be. Hannah passed away suddenly in 1923 seven years to the day after her son’s death at Fromelles. Will disposed of the brickyard and lived on in the home in Thistle St until his death in 1935.