George Harold HALL

Eyes brown, Hair brown, Complexion fair

James and George Hall - Raised as Brothers, Lost to War

With thanks to David Wright for his contribution towards this story

Can you help find James?

James was killed in Action at Fromelles. As part of the 32nd Battalion he was positioned near where the Germans collected soldiers who were later buried at Pheasant Wood. There is a chance he might be identified, but we need help.

In 2008 a mass grave was found at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with identification.

We are still searching for suitable family DNA donors for James.

If you know anything of contacts for James in Australia or England, please contact the Fromelles Association.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

Early Life

James Jones Hall was born in Sydney in 1898, the eldest child of Fanny Hall. Fanny was unmarried and living with her parents, Thomas William Hall and Harriett Hall (née Smith), at 14 Brodie Street, Camperdown NSW. Thomas and Harriet still had young children of their own in their household – George 5, Alfred 7, Frederick 12, Stephen 14 and David 16. Their other son, Thomas was 22. The Hall family had emigrated to Australia from Derbyshire in 1881 aboard the Earl Dalhousie.

James’ grandparents, Harriett and Thomas, had initially settled in Sydney, then in Brisbane, where several of their children were born, before finally returning to Sydney in the early 1890s.

James was likely considered a son of the family rather than a grandson — a not uncommon arrangement when unmarried daughters had children in working-class communities of the time. However, just months after James was born, his grandmother Harriett passed away. Harriett was buried in Waverley Cemetery, alongside her mother Ann Smith, who had been a central matriarchal figure.

With Harriet gone, Fanny’s role helping with raising the children would have increased. Given their ages, George and James grew up more like brothers than uncle and nephew, sharing a close bond. In 1903, Fanny married Thomas McCann, a labourer, and together they raised a large family, with James gaining four half-siblings:

- Winifred Sara McCann (1903–1989)

- Thomas Frederick McCann (1910–1953), who later served in WWII

- Norman “Norrie” Joseph McCann (1914–1984), who also served in WWII

- Harold J. McCann (1921–1921), who died in infancy

With Fanny having raised George from a young age, he may have continued to live with the McCann family - when he enlisted he listed their address and Fanny as his next of kin.. James kept the Hall surname. After his death, Fanny did try to have his records changed to McCann. After his education, James worked as a Barrister’s clerk.

James was especially close to his uncle, George Harold Hall — just five years his senior. George was the youngest of Harriett nine children, born in Sydney. In 1898, George's mother Harriet passed away. From that point, George was raised by his older sister Fanny — who by then was already raising her own infant son, James. The two boys grew up more like brothers than uncle and nephew, sharing a close bond.

George had several older siblings, including:

- Lydia Hall (b. 1873), married Frederick Crouch and settled in Brisbane

- Thomas Hall (b. 1876), married Ellen Evans and had four children

- Fanny Hall (b. 1880), married Thomas McCann and raised a large family, including her son James Hall of the 53rd Battalion

- David Hall (b. 1882), later took the surname Hall-Lemmon and had five children

- Stephen Hall (b. 1884), moved to New Zealand

- Frederick Hall (b. 1886), had a large family and maintained family ties

- Frank Hall (b. 1888), served in WWI and later settled in England

- Alfred Hall (b. 1891), lived in Queensland and died in 1943

Off to War

George was the first to enlist, 14 January 1915, and he was assigned to the 1st Battalion. He left Australia on 8 April 1915 aboard the HMAT A15 Star of England and then took part in the Gallipoli campaign. He was wounded on 24 July 1915 with a gun shot wound to the eye (likely shrapnel), but returned to his unit after treatment. George left Gallipoli for Egypt in December 1915 at the end of the campaign. James enlisted on 6 July 1915 at Liverpool, New South Wales, aged 18, and was assigned to the 11th Reinforcements, 2nd Battalion.

At the time, he was living with his mother and younger siblings at 6 Broughton Street, Woolloomooloo. His records note that he had previoiusly participated in the 25th Avenue Compulsory Training Scheme, a local district of Australia's peacetime military training program.

After a short period of military training, James embarked from Sydney aboard HMAT A14 Euripides on 3 November 1915, headed for Egypt. After his arrival he went the training camp at Tel-el-Kebir, which was about 110 km northeast of Cairo. The 40,000 men in the camp were comprised of Gallipoli veterans and the thousands of reinforcements arriving regularly from Australia. With the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five, major reorganisations were underway.

The 53rd Battalion was formed on 16 February 1916 and was made up of Gallipoli veterans from the 1st Battalion and the new recruits from Australia. The Gallipoli soldiers in the 53rd were not slow in pointing out to whoever would listen that they were the “Dinkums” and the new recruits were the “War Babies”. Source: - AWM4 23/70/1, 53rd Battalion War Diaries, Feb-July 1916, page 3

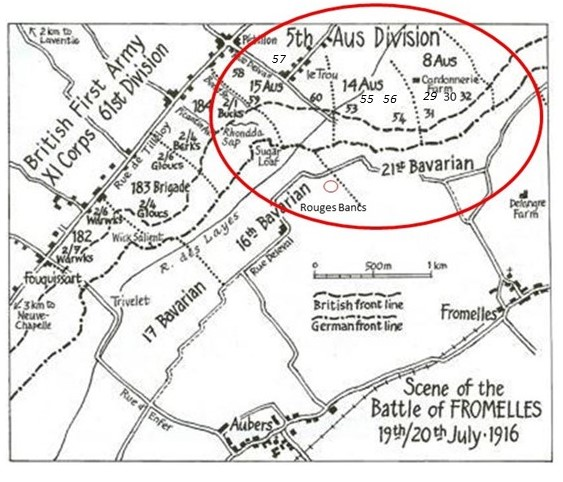

“Dinkum” George and “War Baby” James were reunited, but for a short time only as George was then transferred to the 14th Machine Gun Company (MGC) in early March 1916. The 14th MGC was attached to the 14th Brigade of the 5th Australian Division and tasked with supporting the 53rd and 54th Battalions during the planned assault at Fromelles. The brothers would be fighting side by side, but in different roles.

George was promoted to Lance Corporal just 8 days before the battle. James’ training with the 53rd continued. In March they were sent to Ferry Post, on foot, a trip of about 60 km that took three days. It was a significant challenge, walking over the soft sand in the 38°C heat with each man carrying their own possessions and 120 rounds of ammunition. Many of the men suffered heat stroke.

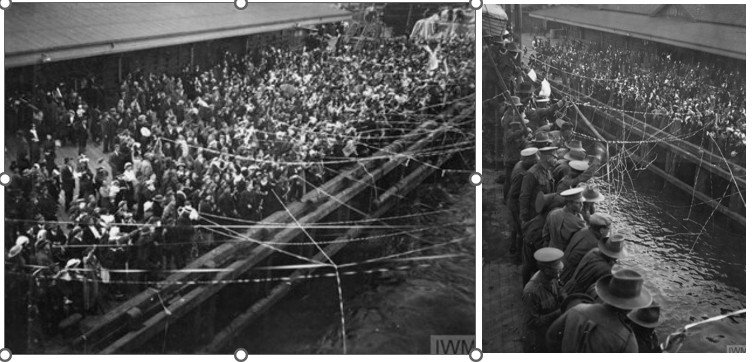

Once there, James remained at Ferry Post guarding the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army until 16 June when the 53rd began the move to the Western Front. 32 officers and 958 soldiers of the 53rd left Alexandria on 19 June on the troopship HMT Royal George, bound for Marseilles, France to become part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front.

They arrived in Marseilles on 28 June and immediately entrained for a 62-hour journey north to Hazebrouck before finally marching into the camp at nearby Thiennes in northern France. During their trip it was noted that their ‘reputation had evidently preceded them’, as they were well received by the French at the towns all along the route.

Source - AWM4 23/70/2 53rd Battalion War Diaries February - June 1916, p. 4

This area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long.

The Battle of Fromelles

On 8 July, the 53rd began a 30 km march to Fleurbaix and were settled into billets there on 16 July. Early the next morning, the 53rd were moved straight into the front lines for the main attack, but it was cancelled due to bad weather.

The delay proved agonising. Private Jim Granger (4784), a young Dorrigo soldier, described the tension:

“We were held in suspense for three days… like a criminal waiting to hear the verdict. We had no dugouts where we were in the supports and shrapnel was bursting all round.”— Private. Jim Granger, 53rd Battalion

On the 19th, heavy bombardment was underway from both armies by 11 AM. At 4 PM the 54th rejoined on their left. All were now in position for battle. George’s 14th MGC was positioned near “Pinney’s Avenue”, the sap between the 53rd and 60th Battalions. Ten machine-gun teams from the company were to move forward to provide covering fire for the advancing infantry. Zero Hour for the 53rd to advance from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties.

The main objective for the 53rd was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the 53rd and the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfiladed fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 60th and 54th Battalions on their flanks.

The Australians went on the offensive at 5.43 PM. They moved forward in four waves – half of A & B Companies in each of the first two waves and half of C & D in the third and fourth. They did not immediately charge the German lines, they went out into No-Man’s-Land and lay down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift. At 6.00 PM the German lines were rushed. The 53rd were under heavy artillery, machine gun and rifle fire, but were able to advance rapidly.

Corporal J.T. James of C Company (3550) reported:

“At Fleurbaix on the 19th July we were attacking at 6 p.m. We took three lines of German trenches”

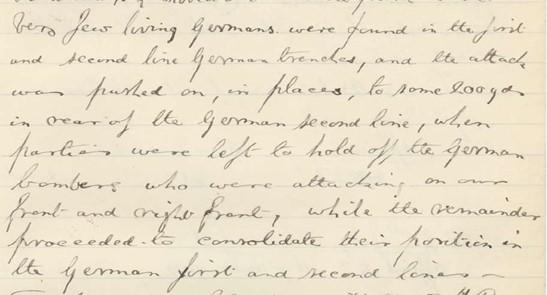

As below, the 14th Brigade War Diary notes that the artillery had been successful and “very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches”, but within the first 20 minutes the 53rd lost ALL the company commanders, ALL their seconds in command and six junior officers.

Source - AWM C E W Bean, The AIF in France, Vol 3, Chapter XII, pg 369

Some of the advanced trenches were just water filled ditches, which needed to be fortified by the 53rd to be able to hold their advanced position against future attacks.

For George, the forward machine-gun positions quickly became untenable as German counter-fire intensified. Conditions faced by George and his fellow machine-gunners are vividly described in Bean’s history, through an eyewitness account from an unnamed NCO:

`“The ditch was full of wounded and dying men—like a butcher’s shop—men groaning and crying and shrieking … So many men were falling that things were clearly wrong; but, when the word about retiring came along, the men received it with: ‘What—retreating? Not on your life!’”

Source: Bean, C.E.W. (1929). Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Vol. III, Chapter XII

They were able to link up with the 54th on their left and, with the 31st and 32nd, occupy a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm, but the 60th on their right had been unable to advance due to the devastation from the machine gun emplacement at the Sugar Loaf.

They held their lines through the night against “violent” attacks from the Germans from the front, but their exposed right flank had allowed the Germans access to the first line trench BEHIND the 53rd, requiring the Australians to later have to fight their way back to their own lines.

Of the 990 men who had left Alexandria just weeks before, the initial count at roll call was 36 killed, 353 wounded and 236 missing. `

“Many heroic actions were performed.”

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The final impact of the battle on the 53rd was that 245 soldiers were killed or died from their wounds and, of this, 190 were not able to be identified.

George’s 14th MGC also suffered heavily. Official records list the company's losses at Fromelles as 11 killed, 28 wounded, and 14 missing—among the highest machine-gun unit casualties in the battle. George was lucky to have survived the battle, but James was last seen during the evening of 19 July. He was “missing in action”.

After the Battle

Fanny was advised on 28 August that James was wounded. However, no further information was forthcoming from the Army. In the months that followed, his mother, Fanny McCann, began a determined and heartbreaking search for answers. She wrote frequently to Base Records, the Red Cross, and the Department of Defence.

On 4 October 1916, from her home at Violet Cottage, East Sydney, she wrote:

“As I have had no letters from him since early in July last I am very anxious about him... This boy was always a good correspondent. I am very anxious not getting news for such a considerable time.”

Fanny continued to get information on her own. In a 20 March 1917 letter to the Army she worte that James “was seen wounded in leg by 3329 Private S F Jobbins, D Company”.

Source - NAA: B2455, Hall, James John – First AIF Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920, page 23

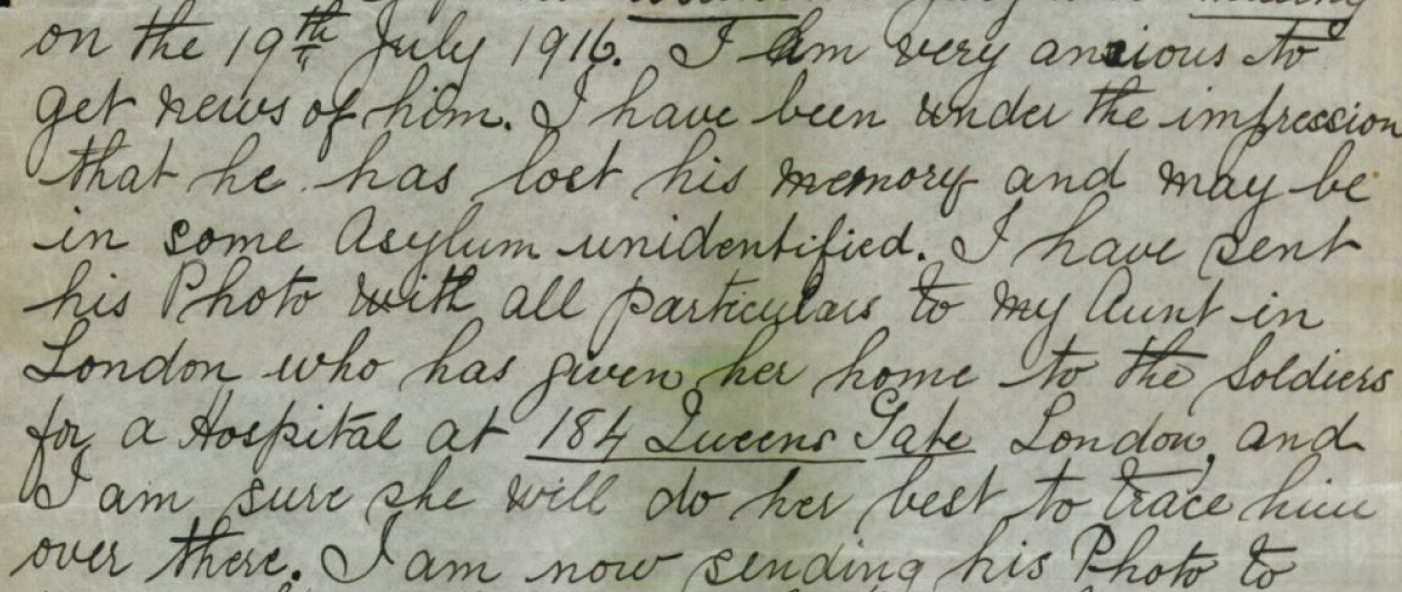

She also wrote that she “…has been under the impression that he has lost his memory and may be in some Asylum unidentified.” (This was not an uncommon hope among many mothers back in Australia.)

Even five years later, in August 1921, she continued to seek what happened to James, noting what she had heard from James’ friend in D Company:

“The closest information I received was from Pte J Coleman D Company 53rd Btn who says my son was among the wounded at Fleurbaix on 19/7/16 and thinks he must have drowned by the water the enemy let go on the boys at that time.

Pvt. Coleman was a mate of my son’s since childhood and was also in the same Company…

Another voice searching for James was his friend Private Henry Richard Benson (2538), who wrote to the Red Cross from England:

“Just a line to ask you would you try and find my cobber. His name is Pte. James Hall, 3318, D. Company, 53rd Batt., 14th Inf. Brigade, A.I.F. He was reported missing on the 19th of July. I have had his photo in the Daily Sketch and the Mirror, but no luck. I had a letter returned today from the Post Office. I was trying to find out whether he is a prisoner in Fritz land.”

James was officially declared killed in action on 19 July 1916 in a 2 September 1917 Court of Enquiry in the Field. In her 1921 letter, the reality still challenged her:

”I myself cannot believe my boy is dead…”

James was awarded the 1914-15 Star Medal, the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll.

He is commemorated on Panel 8 of the VC Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial.

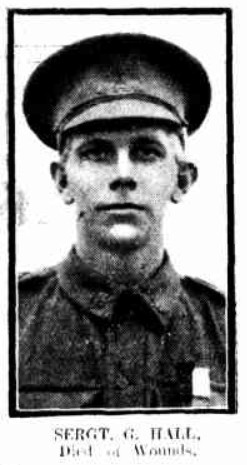

George – Killed at Bullecourt

After surviving Fromelles, George was promoted to Sergeant in August 1916 and he remained on the Western Front. In May 1917, George’s unit was drawn into the Second Battle of Bullecourt — part of a renewed British and Australian effort to breach the Hindenburg Line, east of Arras. The 14th Machine Gun Company supported the 4th and 2nd Australian Divisions, who were tasked with capturing strongly fortified German positions around the shattered village of Bullecourt.

On 3 May 1917, the Australians attacked in the early morning under cover of darkness and a creeping barrage. Over the following week, close-range fighting unfolded among shell holes, broken trenches, and collapsed dugouts and George was mortally wounded. His record states it was a penetrating femur wound. He died on 10 May 1917 at a casualty clearing station - 23 years old.

His death came just two days before Lieutenant Simon Fraser, a fellow Fromelles survivor, was killed in the same battle. Fraser would later be remembered for his famous words, “Don’t forget me, cobber,” spoken while rescuing wounded men under fire at Fromelles — a haunting echo of the cost paid by survivors of that first terrible day.

For Fanny McCann, it was a second devastating loss. Within ten months, she had lost both her only son and the youngest brother she had raised as her own. George was buried in Vraucourt Copse Cemetery, France — Plot III, Row A, Grave 14.

Fanny’s brother Frank also served, but he survived the War. James’s younger half-brothers Thomas and Norman served in the Second World War.

Finding James

David Wright, a Hall family historian recalls:

"Although I knew James’s mother and his half-brother Norrie as a child, I never knew about either James or George. I don’t think my father did either. We were never allowed to talk about the First World War — I guess that’s how the family handled the loss.”

After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including 15 of the 190 unidentified soldiers from the 53rd Battalion.

We welcome all branches of James’ family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification. If you know anything of family contacts, please contact the Fromelles Association. We hope that one day James will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and William’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | James Hall (1898–1916) |

| Parents | Fanny Hall (1880–1965), Sydney, NSW; father unknown |

| Siblings | Winifred Sara McCann (1903–1989) | ||

| Thomas Frederick McCann (1910–1953), WWII veteran | |||

| Norman Joseph McCann (1914–1984), WWII veteran | |||

| Harold J. McCann (1921–1921) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Unknown | ||

| Maternal | Thomas William Hall (1845–1918), Derbyshire/Sydney; Harriett Hall née Smith (1851–1898), Derbyshire/Sydney |

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).