John Patrick CALLAGHAN

Eyes blue, Hair brown, Complexion sallow

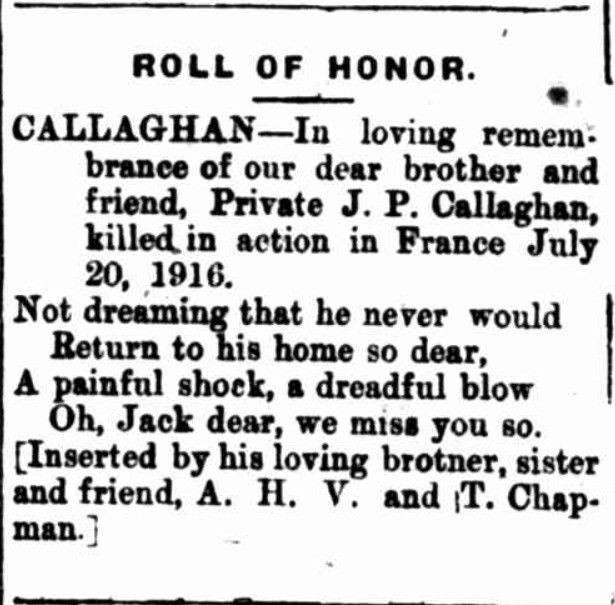

John Patrick Callaghan – “We miss you so”

Can you help us identify Jack?

John Patrick Callaghan, known as Jack, was killed in action at Fromelles on 19 July 1916 while serving with the 30th Battalion.

We are searching for living descendants of Jack’s extended family to help identify his remains through DNA testing.

To register as a potential DNA donor or to find out more, please see the DNA summary below.

Early Life

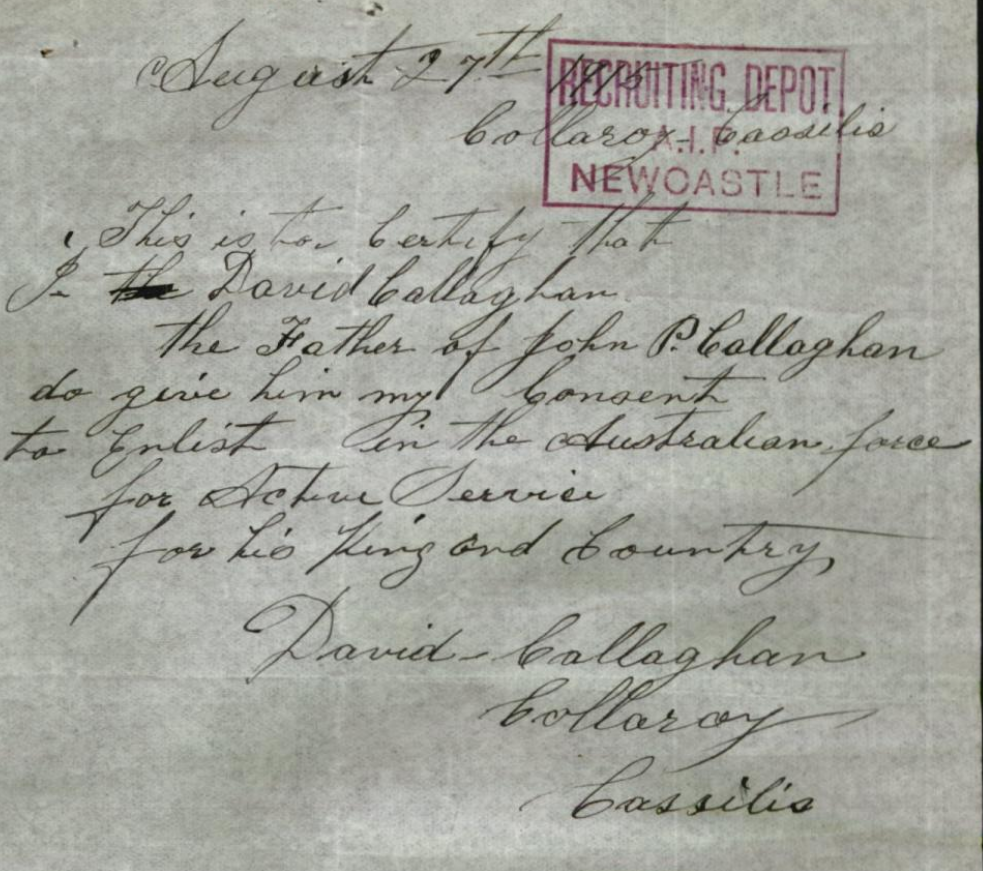

John Patrick Callaghan, known as Jack, was born in 1897 in the rural town of Cassilis, located in the Upper Hunter region of New South Wales. He was the second child and eldest son of David Joseph Callaghan, an immigrant from County Cork, Ireland, and Esther Caroline Callaghan (née Lee), a local woman from Merriwa. The couple had married in Merriwa on 26 February 1895 and settled at Collaroy Station, near Cassilis.

Jack grew up in a large Catholic family on the New South Wales frontier.

The eight children of David and Esther were:

- Mary Ann Callaghan (1895–1957), who married John Bailey

- John Patrick Callaghan (1897–1916), killed at Fromelles

- Cecilia Hannah Callaghan (1898–1959), who married Arthur Chapman

- Catherine Mary Callaghan (1900–1926)

- David Joseph Callaghan (1902–1946), who married Charlotte Hermitage

- Alfred James Callaghan (1906–1946)

- Timothy Arthur Callaghan (1908–1931)

- Margaret E. M. Callaghan (1910–1921)

In 1915, Jack’s younger sister married Arthur Chapman and Jack was the best man.

The family later resided at Coolie Cottage, Merriwa — a small township that maintained strong Irish and farming traditions. Jack's early years were shaped by rural labour and close community life. Like many boys of his generation, he left school young and took up work as a labourer to help support the family. He was just shy of his 19th birthday when he enlisted to serve in the First AIF, driven by a combination of loyalty, adventure, and a desire to stand alongside his mates.

Jack was also closely related to two other soldiers who served in the war:

- His first cousin James Joseph Lee (#4533) of Merriwa, who served with the 54th Battalion

- James Lee’s cousin William Henry Turner (#3606), also of the 54th Battalion

Off to War

With his father’s written permission, Jack enlisted at Newcastle on 31 August 1915, just weeks before his 19th birthday.

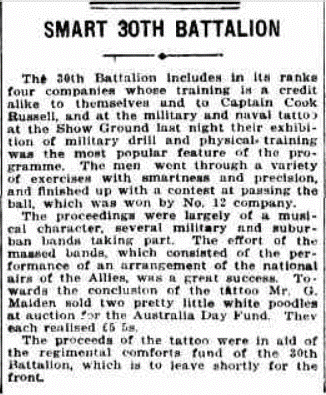

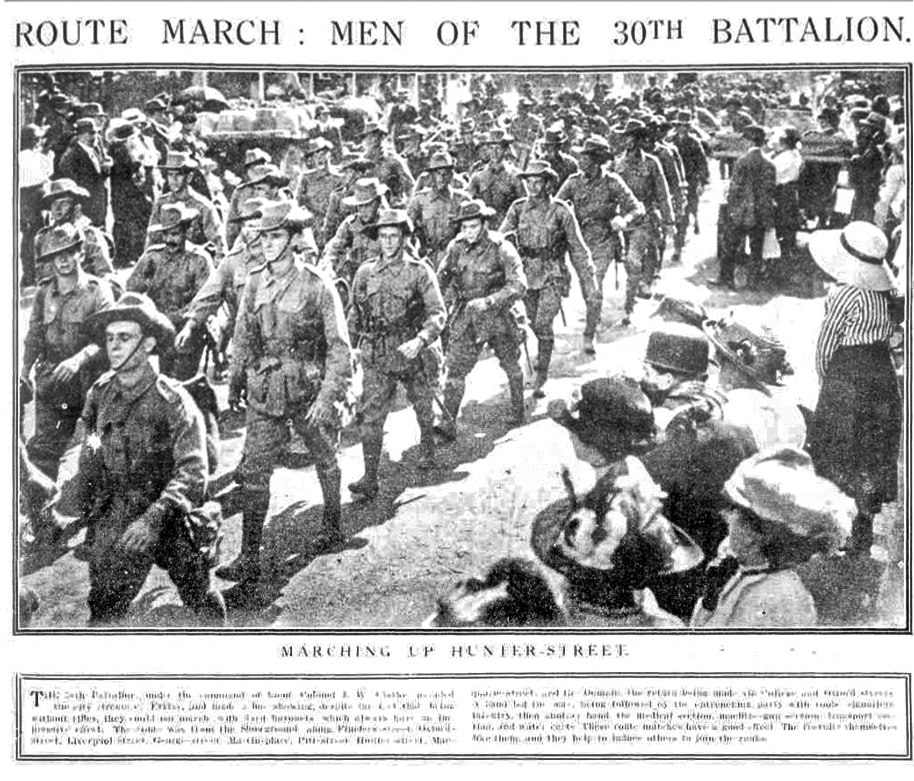

He was posted to the 3rd Reinforcements of the 30th Battalion, part of the 8th Brigade in the newly formed 5th Australian Division. Training began at Liverpool Camp before the battalion moved to the Royal Agricultural Showgrounds in Sydney for final preparations.

On 16 February 1916, Jack embarked from Sydney aboard HMAT A70 Ballarat, bound for Egypt. He disembarked at Suez on 23 March, nearly five weeks after leaving Australia. Like many young reinforcements, Jack spent his first weeks abroad adjusting to the heat, desert conditions, and intensive military drills. The men of the 30th Battalion were initially stationed at Ferry Post, tasked with defending the Suez Canal and undergoing further training.

By June 1916, the 5th Division was on the move. Jack and his battalion embarked for France from Alexandria on 16 June, arriving in Marseilles on 23 June. The contrast between the Egyptian desert and the fertile fields of France was striking, as noted by Private F.R. Sharp of the same unit:

“From the time we left Marseilles until we reached our destination was nothing but one long stretch of farms and the scenery was magnificent... France is a country worth fighting for.”

After a long 60-hour train journey, the battalion reached Hazebrouck and encamped at Morbecque on 29 June. Over the next few weeks, they underwent further training — including in the use of gas masks — and were gradually moved closer to the front. By 10 July, Jack and his comrades were in the front lines for the first time near Erquinghem. They endured German bombardment and began preparing for a major operation to take place later that month.

Battle of Fromelles

On 19 July 1916, Jack and the men of the 30th Battalion were ordered into their first major engagement on the Western Front. Just four weeks after arriving in France, they were thrust into a poorly planned and disastrously executed assault that would become Australia’s bloodiest 24 hours of the First World War.

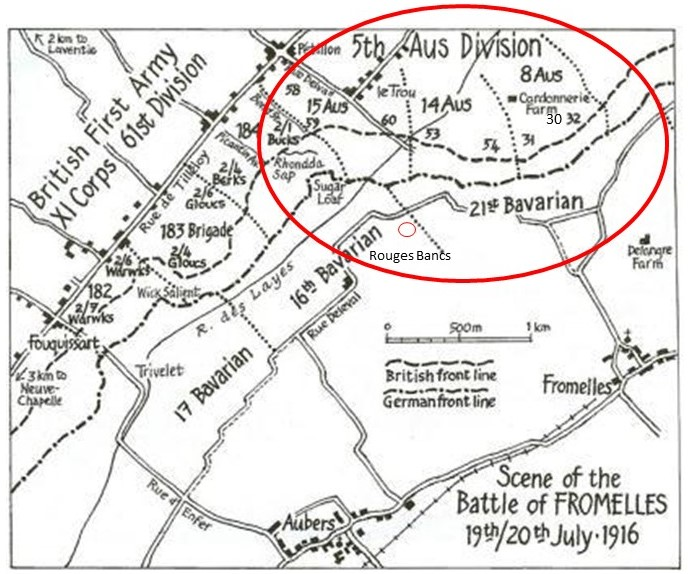

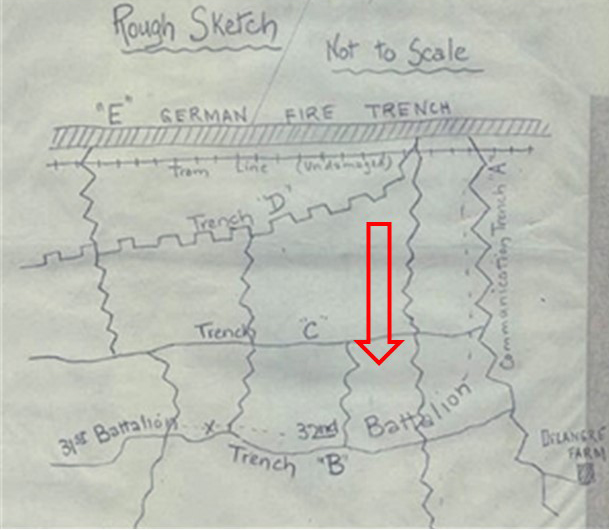

The 30th Battalion, part of the 8th Brigade of the 5th Australian Division, was tasked with a support role in the upcoming assault on the German lines near the village of Fromelles, close to Fleurbaix. The primary attack would be carried out by the 31st and 32nd Battalions, while the 30th was responsible for digging communication trenches, carrying ammunition and supplies, and acting as reserve forces if the situation demanded. At 5.53 PM, the men of the 32nd Battalion went over the top, followed five minutes later by the 31st.

They were immediately met with intense machine gun fire, particularly from a fortified German position at Delangre Farm, and sustained heavy casualties. Despite this, the Australians managed to reach and occupy the German front line trench — known as Trench B — by 6.30 PM. But it was a shallow, muddy ditch and offered little in the way of protection. “Practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom.”

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, p. 11

The worsening situation on the front line forced commanders to send in support from the 30th Battalion — including Jack — earlier than planned. This disrupted the flow of ammunition and left carrying parties vulnerable in the open, exposed to German fire. By 8.30 PM, the Australians’ left flank was under fierce bombardment. Orders came through that “the trenches were to be held at all costs.”

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, p. 12

At 10.10 PM, the 30th Battalion was formally committed to direct combat. But already, the situation was dire. Lieutenant-Colonel Clark reported:

All my men who have gone forward with ammunition have not returned. I have not even one section left.

Fighting continued throughout the night. Some Australians attempted to press further beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades and under fire from both German machine guns and misdirected Australian artillery. Isolated and surrounded, many were killed or captured.

At 4.00 AM, German forces counterattacked from the Australian left flank, infiltrating rear trenches that had been left lightly defended during the earlier push forward. By 5.30 AM, German troops were attacking from both flanks:

"The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans' Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

By 10.00 AM on 20 July, the Australian advance had completely failed, and the surviving troops were pulled from the line. No ground had been gained, and over 5,500 Australian casualties were sustained in a single night. The 30th Battalion alone recorded 54 killed, 230 wounded, and 68 missing.

Jack was reported missing in action and later declared killed in action. Like so many others, his body was never recovered, and no eyewitness accounts of his death survive.

As Private Jim Cleworth of the 29th Battalion later said of the battle:

The novelty of being a soldier wore off in about five seconds. It was like a bloody butcher’s shop.

After the Battle

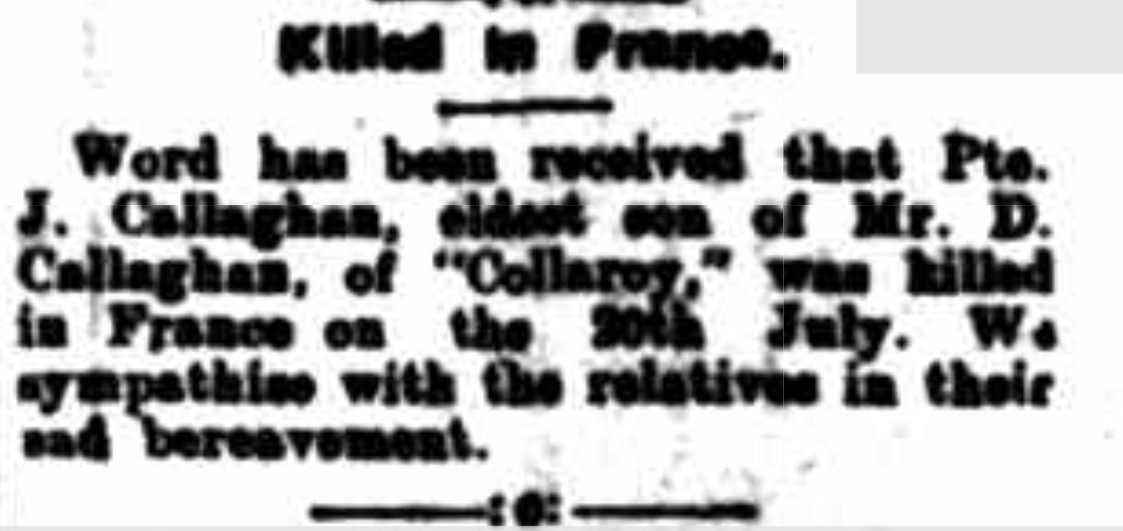

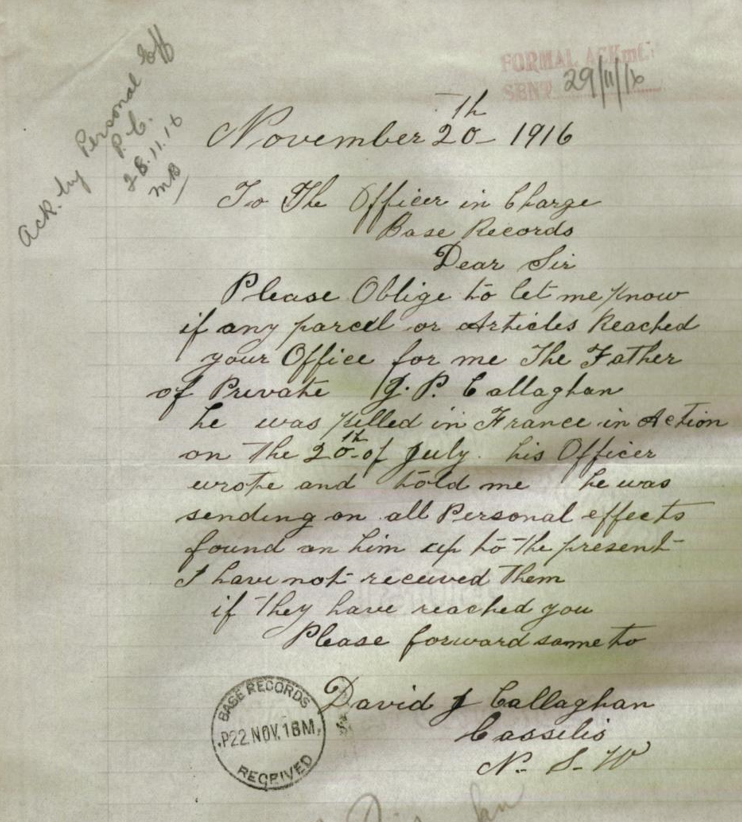

In the aftermath of the failed assault at Fromelles, the battlefield was strewn with the bodies of Australian soldiers. Many, including Jack, were reported missing. For months, families back home endured silence and uncertainty, hoping their sons might still be alive as prisoners of war.

But as weeks passed and no word came, Jack’s name was officially listed among the dead:

“News has been received of the death of Private J. Callaghan, eldest son of Mr. D. Callaghan, of Collaroy Station, Cassilis, who was killed in France on July 20th.”

No remains were ever recovered or identified for Jack. Like many grieving families, the Callaghans received only a brief notice of their son’s death, along with his British War Medal, Victory Medal, a Memorial Scroll, and a profound silence that lingered for generations. With no body to bury, the pain of loss remained unresolved.

Jack was one of the many young reinforcements of the 30th Battalion who vanished during the chaos of the Battle of Fromelles. His body was never recovered, and no burial site was identified.

He is formally commemorated at:

- V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial, Fromelles, France – Panel No. 2

- Australian War Memorial, Roll of Honour – Panel 116, Canberra, ACT

- Merriwa War Memorial

- Cassilis War Memorial Park and Memorial Gates

Can you help find Jack?

More than a century later, Jack remains among the unidentified dead of Fromelles. His name is included in efforts by the Fromelles Association of Australia to identify the missing and give names back to the unknown soldiers buried in mass graves at Pheasant Wood Cemetery.

His story is not forgotten.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | John Patrick Callaghan (1897–1916) |

| Parents | David Joseph Callaghan (born County Cork, Ireland, 1860s?) and Esther Caroline Lee (1874–1951), of Merriwa, NSW |

| Siblings | Mary Ann Callaghan (1895–1957) – m. John Bailey | ||

| Cecilia Hannah Callaghan (1898–1959) – m. Arthur Chapman | |||

| Catherine Mary Callaghan (1900–1926) | |||

| David Joseph Callaghan (1902–1946) – m. Charlotte Hermitage | |||

| Alfred James Callaghan (1906–1946) | |||

| Timothy Arthur Callaghan (1908–1931) | |||

| Margaret E.M. Callaghan (1910–1921) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Patrick Callaghan (1839–1900) and Hannah [surname unknown] | ||

| Maternal | Richard Patrick Lee (1840–1907) and Katherine Mary Burke (1841–1887) |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).