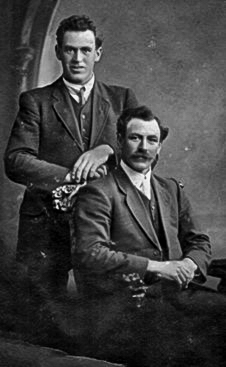

Cecil George HARLAND

Eyes brown, Hair dark brown, Complexion medium

Finding Cecil George Harland

Can you help us identify Cecil?

Cecil was killed in Action at Fromelles. As part of the 32nd Battalion he was positioned near where the Germans collected soldiers who were later buried at Pheasant Wood. There is a chance he might be identified, but we need help. We are still searching for suitable family DNA donors.

In 2008 a mass grave was found at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 (Australian) bodies they recovered after the battle.

If you know anything of contacts for Cecil here in Australia or his relatives Durham, England, please contact the Fromelles Association.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

We would like to thank Cecil’s great nephew John Przyibilla for his contributions to this story and Fromelles Association researcher Carol Worthington for her extensive family research.

Cecil’s Early Life – a Mother’s Challenge

Cecil was born on 3 October 1890 in Adelaide, South Australia, the third child of Mary Ann (nee Clark) and John George Harland. Cecil’s siblings were Sidney and Edith. Cecil’s father had been born in Wolviston, Durham, England and his mother in South Australia. The family’s early life was challenging. Just six months before Cecil was born, his two-and-a-half years old sister died, most likely from a common childhood illness. Then when Cecil was 13 months old, his father was killed in a horse-and-trap accident at Pine Grove, leaving Mary Ann as a 26 year-old widow after just six years of marriage.

Cecil attended State School and then became a plumber’s fitter. His brother Sidney became a carpenter and builder in the Flinders Ranges area. Before he enlisted, Cecil was working as a quality controller on the pipework for the Umberumberka Waterworks, near Broken Hill NSW. The project was an important part of the growth of Broken Hill and is now one of the most complete steam-driven water supply systems left today. He must have done his job well, even in recent years the project received an award from Engineers Australia for the quality of the Pumping Station.

Quality obviously ran in the family. John Pryzibilla, Sidney’s grandson, says that “Sidney’s metal-hinged wooden tool box is still sturdy, and resides in my garage. It's of a size to put on a horse-drawn cart!”

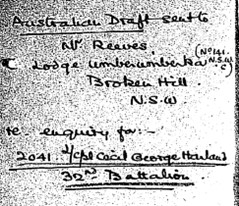

Cecil was a member of the local Masonic Lodge at Umberumberka. He must have been well respected, as the members of the Lodge took it upon themselves to contact the Army seeking details when they learned of Cecil’s death.

Off to War

Just days after his 25th birthday, Cecil signed up to go to war - 8 October 1915 at Adelaide, South Australia. He did his initial military training at the Morphetville camp in Adelaide. Having worked in a responsible position prior to signing up, he was promoted to Corporal on 1 December. Cecil’s reinforcements left on 7 February 1916 from Adelaide, South Australia on board HMAT A28 Miltiades, arriving in Suez on 11 March. They were finally joined with the full Battalion on 1 April. He was returned to being a Private but was re-promoted to Lance Corporal on 26 May. Training and guarding the Suez Canal were at Duntroon Plateau and Ferry Post until the end of May.

Their last posting in Egypt was a few weeks at Moascar. One soldier’s diary complained of being “sick up to the neck of heat and flies”, of the scarcity of water during their long marches through the sand and he described some of the food as “dog biscuits and bully beef”. He did go on to mention good times as well with swims, mail from home, visiting the local sights and the like. Source AWM C2081789 Diary of Theodor Milton PFLAUM 1915-16, page 29, page 12 You can read Theodor’s Soldier Story here.

The call to support the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front came in mid-June. Cecil left from Alexandria on the ship Transylvania on 17 June 1916 and arrived at Marseilles, France on 23 June 1916. He then had a two-day train trip to Steenbecque. The route took them to a station just out of Paris, within sight of the Eiffel Tower, through Bologne and Calais, with a view of the Channel, before disembarking and marching to the camp at Morbecque, about 30 kilometres from Fleurbaix.

Theodor Pflaum (No. 327) wrote about the trip in his diary:

“The people flocked out all along the line and cheered us as though we had the Kaiser as prisoner on board!!”

Training continued with a focus on bayonets and the use of gas masks, assuredly with a greater emphasis given their position near the front.

Fromelles

The 32nd moved to the front on 14 July and Cecil was into the trenches for the first time on 16 July, only three weeks after arriving in France.

On the 17th they were reconnoitering the trenches and cutting passages through the wires, preparing for an attack, but it was delayed due to the weather. D Company’s Lieutenant Sam Mills’ letters home were optimistic for the coming battle:

“We are not doing much work now, just enough to keep us fit—mostly route marching and helmet drill. We have our gas helmets and steel helmets, so we are prepared for anything. They are both very good, so a man is pretty safe.”

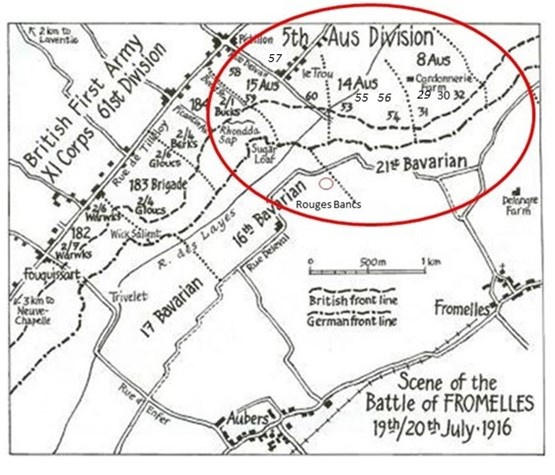

The overall plan was to use Brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault of the German trenches at Fromelles. The 32nd Battalion’s position was on the left flank, with only 100 metres of no man’s land to get the German trenches. As they advanced they were to link up with the 31st Battalion on their right.

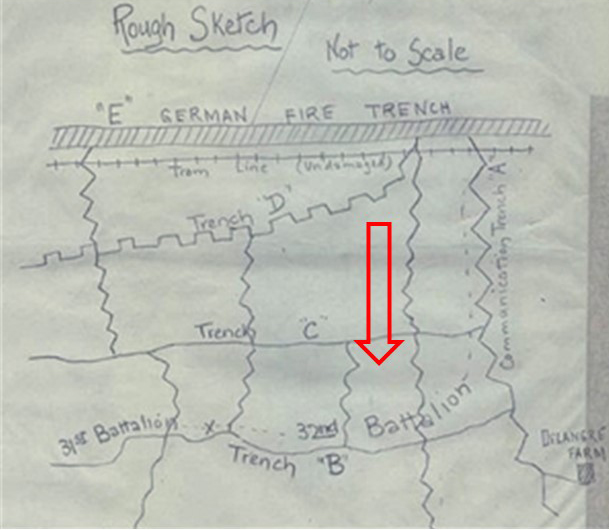

However, their position on the extreme left flank made their job more difficult, as not only did they have to protect themselves while advancing, but they also had to block off the Germans on their left, to stop them from coming around behind them. On the 19th, all were in position by 5.45 PM and the charge over the parapet began at 5.53 PM. A & C Companies were the first and second waves to go, and Cecil’s B Company & D Company in the third and fourth. They were successful in the initial assaults and by 6.30 PM were in control of the German’s 1st line system (map Trench B), which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

Source AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

Unfortunately, with the success of their attack, ‘friendly’ artillery fire caused a large number of casualties. They were able to take out a German machine gun in their early advances but were being “seriously enfiladed” from their left flank.

By 8.30 PM their left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and the 32nd was told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

Fighting continued through the night. Up ahead, the Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine gun fire from behind and from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map). Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers of the 32nd.

At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance they could offer was with rifles:

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

What was left of the 32nd had finally withdrawn by 7.30 AM on the 20th. The initial roll call count was devastating – 71 killed, 375 wounded and 219 missing. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large amount of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The final impact was that 225 soldiers of the 32nd Battalion were killed or died from wounds sustained at the battle and, of this, 166 were unidentified.

Lieutenant Sam Mills survived the battle. In his letters home, he recalls the bravery of the men:

“They came over the parapet like racehorses……… However, a man could ask nothing better, if he had to go, than to go in a charge like that, and they certainly did their job like heroes."

After the Battle

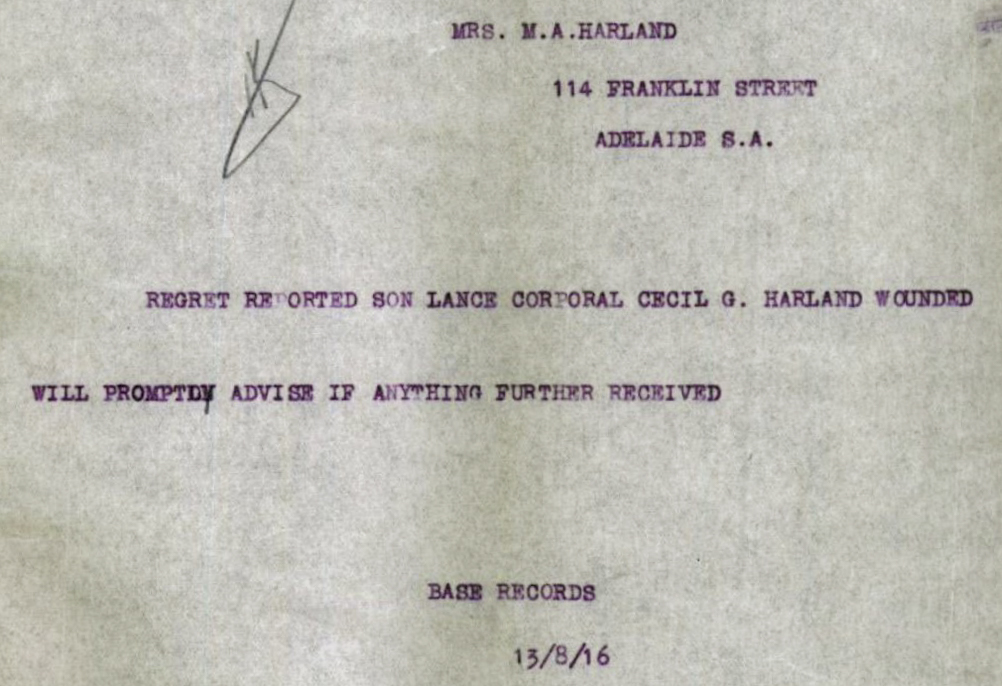

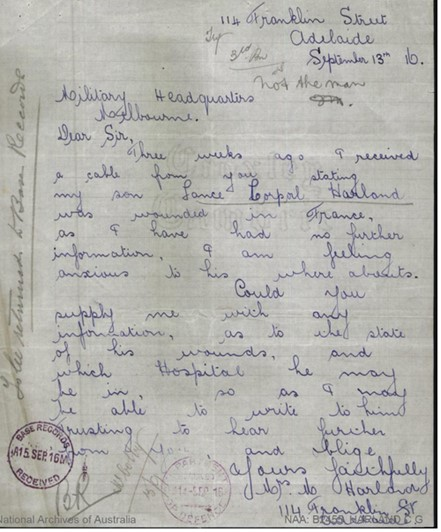

Cecil and his mates had been in the advance area of the Australians’ charges and Cecil was among the many who were missing at roll call after the battle. The heavy toll from the battle was reported back home, but hard news was scarce. While the source of the info is unknown, on 18 August, the Army advised Cecil’s mother that he had been wounded.

Given the battle, wounded was a ‘good’ outcome, but no further information was able to be provided and Mary Ann was understandably anxious to hear more.

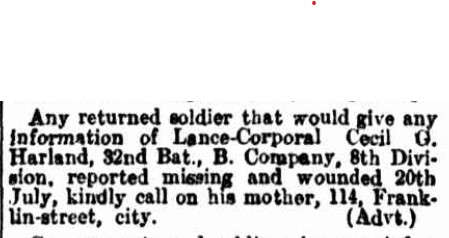

Extensive efforts were underway to document all of the casualties from the battle, but by mid-October Cecil had not been located and was now officially ‘missing’. Thousands of families suffered greatly with the grief of their unconfirmed loss, not knowing where their loved one lay , but sustaining hope that they may still be alive. Mary Ann made further enquiries through the Ministry of Defence in November, but there was no further information to be had. There was also an advertisement seeking news that was in the newspapers in April 1917.

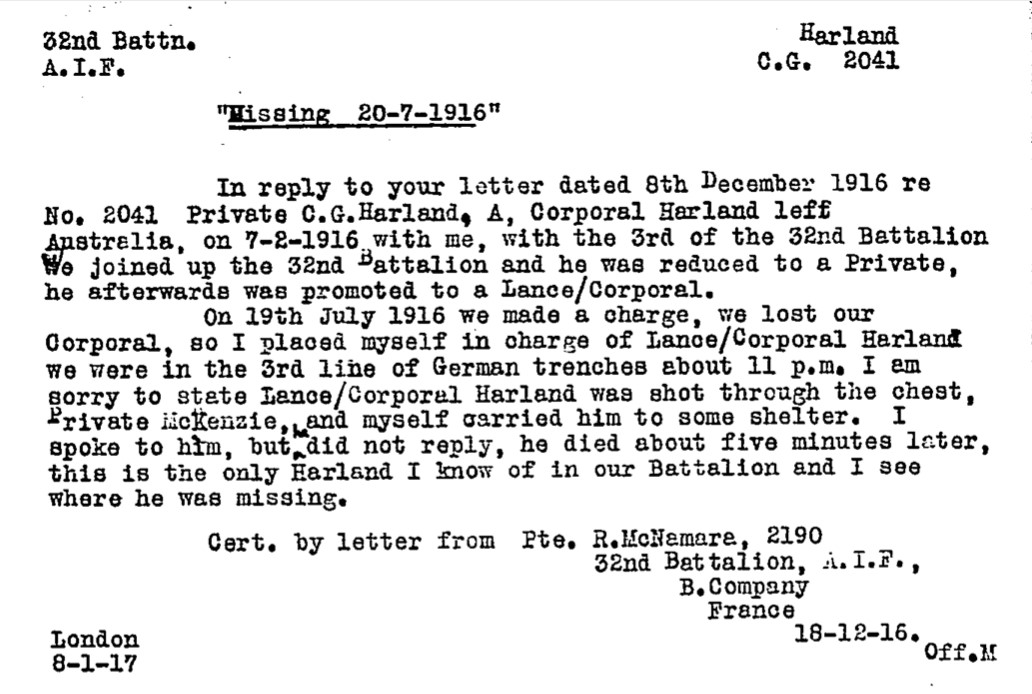

Hard news about Cecil’s fate did come from a Red Cross witness statement, taken on 18 December. Cecil’s mate Robert McNamara (2190) described that at about 11.00 PM on the 19th that they were in the third German trench when Cecil was shot through the chest. Robert and Private McKenzie carried him to some shelter but he died shortly afterwards. With the chaos of the battle and the 32nd soldiers being well advanced, they were unable to carry him back to the Australian lines.

While this and other Red Cross reports were available by early 1917, the Army was also searching POW camps, etc. for the missing before reaching conclusions for the large number of casualties. However, the family letters reflect a sorrowful insight into the grieving families as they sought a description of the events that took place to achieve closure. It was not until a formal “enquiry in the field” was held on 12 August 1917 that Cecil was formally declared as having been killed in action, more than a year after the battle. No closure for the Harland family.

Cecil was clearly missed:

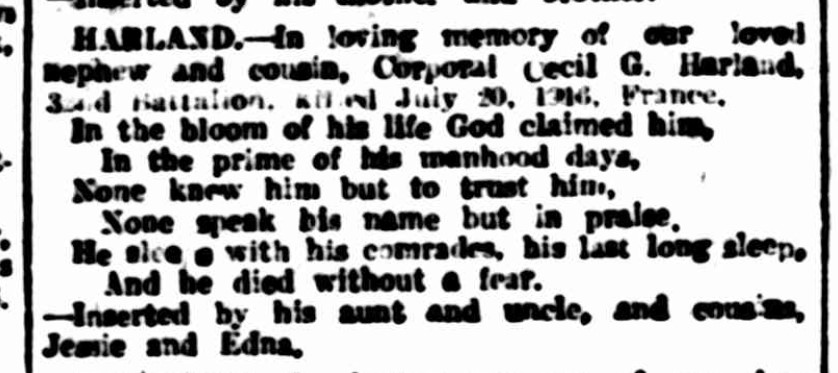

HARLAND. – In loving memory of our dear son and brother, SOM, Corporal Cecil George Harland, killed in action, July 19th, 1916.

Died, that is all they could tell us.

Of the noble boy we loved so well.

Cecil was awarded the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll. He is commemorated at :

- V.C. Corner (Panel No 4), Australian Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles, France,

- the Adelaide National War Memorial,

- the Australian War Memorial,

- the Baulkham Hills William Thompson Masonic School War Memorial

- and the Sydney United Grand Lodge Honour Roll.

Having lost two of her three children and her husband, Mary Ann’s heartbreaks were still not over; Sidney passed away in 1919 from the Spanish Flu. Sidney, Cecil and their grandfather James share a memorial.

Can Cecil Still be Found?

A mass German grave was discovered at Fromelles 92 years after the battle. It contained the remains of 250 Australian soldiers. Since the discovery, much effort has been undertaken by the Army and the Fromelles Association of Australia to identify these soldiers by finding family members and using DNA matching techniques. As of 2024, 180 of the 250 soldiers have been identified. This includes 41 of the 166 missing soldiers from the 32nd Battalion.

Cecil was killed near the area of this mass grave, so he could well be one of the yet unidentified soldiers. We just need to find relatives to donate DNA. John Pryzibilla and FAA researchers have been actively seeking the ‘correct’ donors.

A descendant carrying mt DNA has donated a sample, but we also require another mt sample.

Also needed are two Y samples, from a male relative to confirm if Cecil's remains lie at Pheasant Wood Cemetery. Unfortunately, the Harland male DNA line goes back to an illegitimate birth in the UK, effectively complicating matters for finding living relatives who probably do not know anything about Cecil Harland. Until donors can be found, we will never truly know where Cecil George Harland lies. If you know anything of contacts for Cecil here in Australia or his relatives Durham, England, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Family connections are sought for the following soldier

| Soldier | Cecil George Harland (1890 - 1916) |

| Parents | John George Harland (1852-1891), b Wolviston, Durham, England, d Eurilpa South Australia and Mary Ann Clarke ( 1865 – 1931) b Gilles Creek, Kapunda South Australia, d Glenelg South Australia |

| Siblings | Sidney James (1885 – 1919) b Eurilpa, South Australia, d Knightsbridge, South Australia, married Jesse May McArthur | ||

| Edith (1887 – 1890) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | John Harland (1824 - 1851) b Wolviston England, d Wolviston England and Mary Brown (1828-1901) b Easton, Northumberland, England, d Shadforth, Durham, England | ||

| Maternal | James Clarke (1837 – 1912), b Aberdeenshire, Scotland, d Glenelg, South Australia and Bridget Doherty (1832 – 1888), b Kerry, Ireland, d Adelaide, South Australia |

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).