George WESTLAKE

Eyes blue, Hair brown, Complexion fresh

George Westlake

Can you help us identify George?

George was killed in Action at Fromelles. As part of the 32nd Battalion he was positioned near where the Germans collected soldiers who were later buried at Pheasant Wood. There is a chance he might be identified, but we need help. We are still searching for suitable family DNA donors.

A mass grave was found at Fromelles in 2008, a grave that the Germans dug for 250 (Australian) bodies they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, DNA matching from relatives has enabled the identification of 180 of these soldiers.

If you know anything of contacts for George here in Australia or his relatives in England and the US, please contact the Fromelles Association.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

Early Life

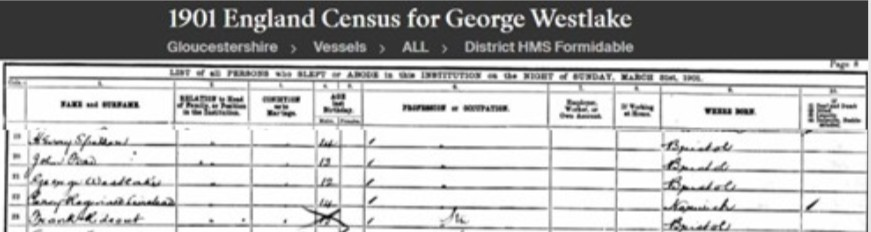

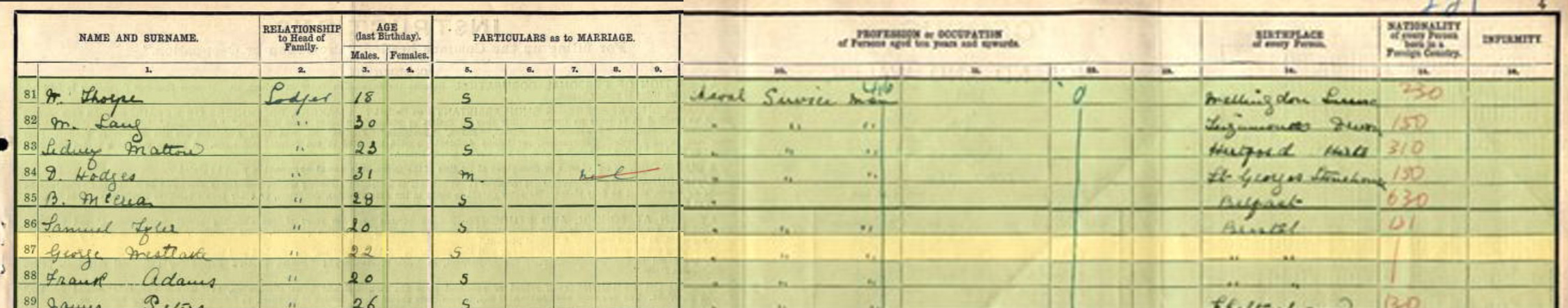

George was born in February 1889 in Bristol, England, but very little is known about his early life. He did have an older brother, Thomas, who was born in June 1883. George’s early life was likely difficult. He was sent to spend time on the HMS Formidable, a ‘training ship’ program that had been set up by several Bristol businessmen who were “concerned about the large number of urchins wandering the city streets.”

He may have spent several periods here, as there are records of him being discharged from the ship in July 1900, but, as above, he was back on board during 1901. His naval training did pay off, however, and in 1911 he was working as a Naval Serviceman in Devon.

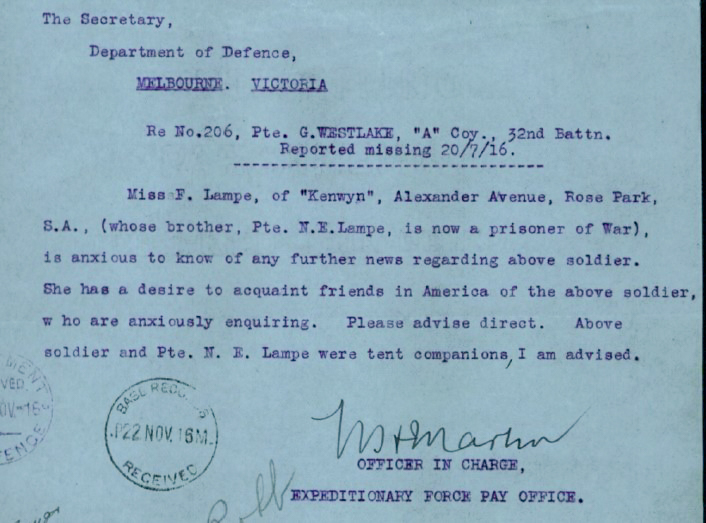

Later, George migrated to Australia, settling in Port Pirie, South Australia. He was working as a Labourer when he enlisted in 1915. One of George’s friends and tent mates in the war was Norman E. Lampe (123). Norman’s sister Frances was the ‘go-between’ the Army and George’s brother who tried to find out about what happened to George during the war.

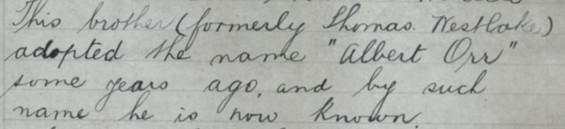

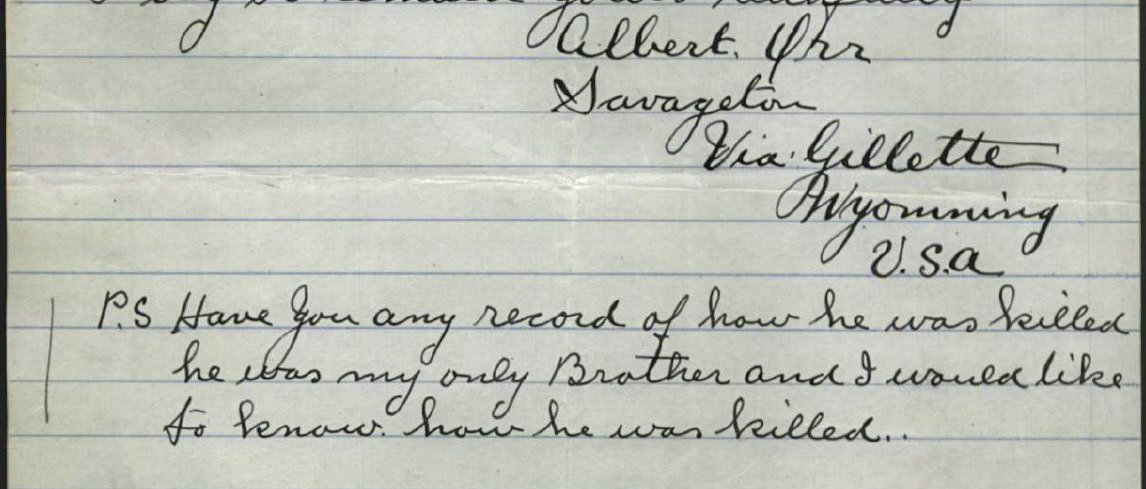

The likely lack of family support for George is also reflected in his brother Thomas’ life. One can conclude his ties to his parents were limited as he later took on an entirely new name, Albert Orr, the name of a friend’s son. Thomas/Albert had become a sailor too, serving in the Navy, but he left the Service in 1905 and emigrated to the US in 1911.

Albert served in WW1 for 19 months with the US Army and at 57 he even filed for enlistment in WW2. He had married Estella Lauderback and they lived outside of Gillette, Wyoming. He passed away in 1959. It is not known if they had any children.

Off to War

George enlisted on 22 July at Keswick, South Australia. He was assigned to ‘Base Infantry’, but then to the newly formed 32nd Battalion, A Company. A and B Companies were made up of recruits from South Australia and C and D Companies came from Western Australia. There was much fanfare about this new battalion in South Australia, with gatherings, community support, such as the Cheer-up Society and reviews of the troops by the Premier.

The men from WA who had been at the Blackboy Hill Camp near Perth arrived in Adelaide at the end of September and the whole battalion was assembled at the Cheltenham Racecourse Camp. Training continued until the battalion departed for Egypt on 18 November 1915, with the unit being split between two troop ships HMAT A2 Geelong and HMAT A13 Katuna. George was aboard the Geelong.

“The 32nd Battalion went away with the determination to uphold the newborn prestige of Australian troops, and they were accorded a farewell which reflected the assurance of South Australians that that resolve would be realized.”

Egypt

The 32nd arrived in Suez on 14 December 1915 and moved to El Ferdan just before Christmas. A month later they marched to Ismailia and then to the major camp at Tel el Kebir where they stayed for February and most of March. Tel-el-Kebir was about 110 km northeast of Cairo and the 40,000 men in the camp were comprised of Gallipoli veterans and the thousands of reinforcements arriving regularly from Australia.

Their next stop was at Duntroon Plateau and then at Ferry Post until the end of May where they trained and guarded the Suez Canal. Their last posting in Egypt was a few weeks at Moascar.

One soldier’s diary complained of being “sick up to the neck of heat and flies”, of the scarcity of water during their long marches through the sand and he described some of the food as “dog biscuits and bully beef”. He did go on to mention good times as well with swims, mail from home, visiting the local sights and the like.

Source AWM C2081789 Diary of Theodor Milton PFLAUM 1915-16, page 29, page 12

You can read Theodor’s Soldier Story here

During their time in Egypt the 32nd had the honour of being inspected by H.R.H. Prince of Wales.

Fromelles

After spending six months in Egypt, the call to support the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front came in mid-June. The 32nd left from Alexandria on the ship Transylvania on 17 June 1916, arriving at Marseilles, France on 23 June 1916 and then immediately entrained for a three-day train trip to Steenbecque. Their route took them to a station just out of Paris, within sight of the Eiffel Tower, through Boulogne and Calais, with a view of the English Channel, before disembarking and marching to their camp at Morbecque, about 30 kilometres from Fleurbaix.

Theodor Pflaum (No. 327) wrote about the trip in his diary:

“The people flocked out all along the line and cheered us as though we had the Kaiser as prisoner on board!!”

Wesley Choat (No. 68), for one, was glad to be out of Egypt, but he was well aware of what laid ahead:

“The change of scenery in La Belle France was like healing ointment to our sunbaked faces and dust filled eyes. It seemed a veritable paradise, and it was hard to realise that in this land of seeming peace and picturesque beauty, one of the most fearful wars of all time was raging in the ruthless and devastating manner of "Hun" frightfulness”.

They were headed to the area of Fleurbaix which was known as the ‘Nursery Sector’ – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times did not last long. Training continued with a focus on bayonets and the use of gas masks, assuredly with a greater emphasis, given their position near the front.

The 32nd moved to the Front on 14 July and George was into the trenches for the first time on 16 July, only three weeks after arriving in France.

On the 17th they were reconnoitering the trenches and cutting passages through the barbed wire, preparing for an attack, but it was delayed due to the weather. D Company’s Lieutenant Sam Mills’ letters home were optimistic for the coming battle:

“We are not doing much work now, just enough to keep us fit—mostly route marching and helmet drill. We have our gas helmets and steel helmets, so we are prepared for anything. They are both very good, so a man is pretty safe.”

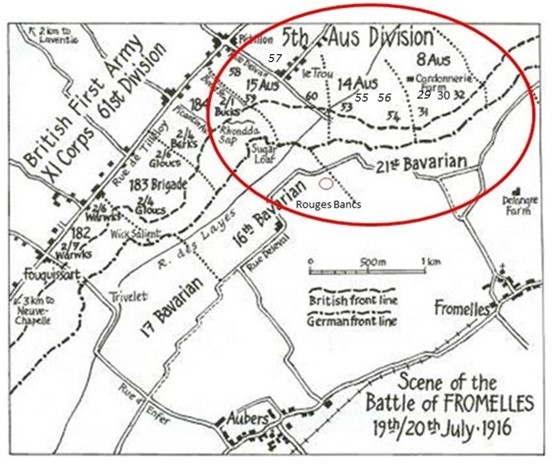

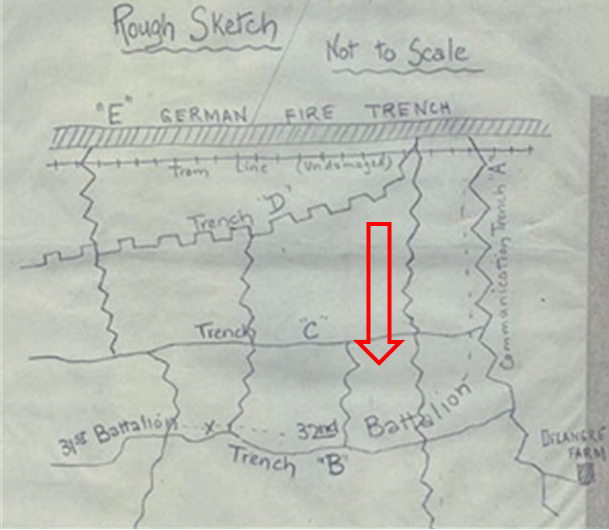

The overall plan was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The 32nd Battalion’s position was on the extreme left flank, with only 100 metres of No Man’s Land to get the German trenches. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 31st Battalion on their right. However, their position made the job more difficult, as not only did they have to protect themselves while advancing, but they also had to block off the Germans on their left, to stop them from coming around behind them.

On the morning of the 18th, George’s A Company and C Company went into the trenches to relieve B and D Companies, who rejoined the next day. The Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties.

The charge over the parapet began at 5.53 PM. George’s A Company were in the first and second waves to go, B & D were in the third and fourth. They were successful in the initial assaults and by 6.30 PM were in control of the German’s 1st line system (map Trench B), which was described as:

“practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

Unfortunately, with the success of their attack, ‘friendly’ artillery fire caused a large number of casualties because the artillery observers were unable to confirm the position of the Australian gains. They were able to take out a German machine gun in their early advances, but were being “seriously enfiladed” from their left flank.

By 8.30 PM their left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and the 32nd were told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine gun fire from behind them from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. In the early morning of the 20th, the Germans began a counterattack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map).

Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to regain that trench and envelop the men of the 32nd. At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance they could offer was with rifles:

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

What was left of the 32nd had finally withdrawn by 7.30 AM on the 20th. The initial roll call count was devastating – 71 killed, 375 wounded and 219 missing, including George. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large amount of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield.

The final impact was that 228 soldiers of the 32nd Battalion were killed or died from wounds sustained at the battle and, of this, 166 were unidentified. Lieutenant Sam Mills survived the battle. In his letters home, he recalls the bravery of the men:

“They came over the parapet like racehorses……… However, a man could ask nothing better, if he had to go, than to go in a charge like that, and they certainly did their job like heroes."

George

George was reported as being Missing in Action in the Adelaide papers by early September. His mate Norman Lampe had been wounded and taken as a Prisoner of War. Norman was not released until January 1919. He returned to Australia. George’s brother in the US was aware of what had happened to him, presumably from information provided by Frances Lampe, and Albert was keen to find out more.

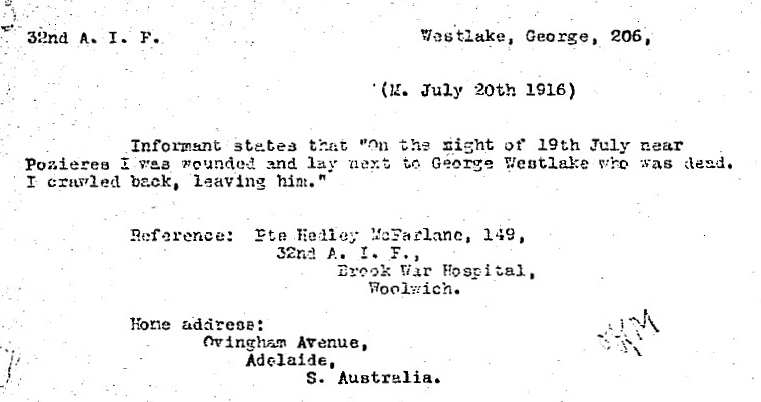

Fellow A Company Private Hedley McFarlane (149) reported that he had been wounded and George had died, but there was little other detail. Hedley survived and returned to Australia after the War. (Note: many soldiers referred to Fromelles as Armentieres.)

Official confirmation that George was Killed in Action did not come until a Board of Enquiry was held in the field on 12 August 1917, as the Army undertook extensive hospital, German POW camp, etc. searches for information before issuing a final determination as to a soldiers’ fate. We do not know how far George had advanced before he was killed.

The declaration of him being Killed in Action cites his death as 20 June, suggesting he could have been in the advanced areas, but we will never know. George was awarded the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal, Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll, which were sent to his brother in the US. Albert also continued to seek additional information about how his brother died.

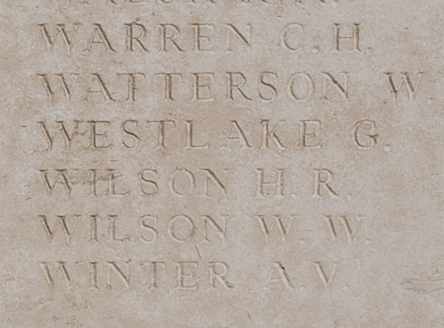

George is commemorated at V.C. Corner (Panel No 6), Australian Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles, France and the Adelaide National War Memorial.

V.C. Corner (Panel No 6), Australian Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles

Will We Ever Know What Happened to George?

A mass grave dug by the Germans that contained 250 bodies from the battle was discovered in 2008. As of 2024, DNA matching from family members has enabled 180 of these soldiers to be identified, including 41 of the 166 unidentified soldiers from the 32nd. George could be one of these soldiers.

If you know anything of contacts for George’s family in Bristol, England or Albert Orr’s family in the United States, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Family connections are sought for the following soldier

| Soldier | George Westlake (1889, 1916) |

| Parents | Unknown – Bristol, England |

| Siblings | Thomas, who took on the name Albert Orr, b Bristol, England, d Gillette Wyoming, USA, m Estella Lauderback, b 11 Nov 1884 d 10 Dec 1942, Gillette Wyoming USA | ||

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Unknown | ||

| Maternal | Unknown |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).