Edgar William PARHAM

Eyes grey, Hair brown, Complexion fair

“Here, Fritz, You’d Better Take This “ - The Story of Edgar William Parham and His Bible

In the chaos of the Battle of Fromelles on the night of 19–20 July 1916, Private Edgar “Ted” Parham lay gravely wounded in the captured German trenches. The fighting had raged for hours, his battalion, the 32nd, had been almost destroyed. As German soldiers moved among the fallen, collecting identity discs, one knelt beside Ted and realised he was still alive. With the last of his strength, Ted reached inside his tunic and drew out the small leather-bound Bible his mother had given him before he left Australia. Handing it to the puzzled soldier, he said quietly

“Here, Fritz, you had better take this.”

You can read his story below in more detail.

Early Life

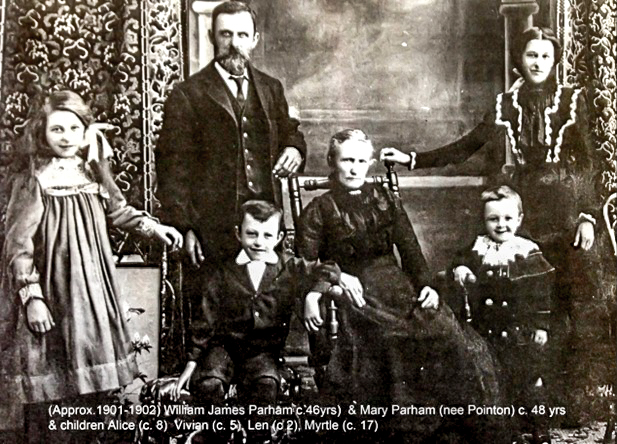

Ted Parham was born on 19 January 1878 at Ward’s Belt near Gawler, South Australia, to William James Parham and Mary Parham (née Pointon). He was part of a large South Australian family with deep roots in the district; his paternal grandparents were Silas Thomas Parham (1815–1878) and Mary White (1815–1896), while his maternal grandparents were Jeremiah L. Pointon (1824–1906) and Frances Brown.

The Parham family later moved to Wandearah, where Edgar attended Wandearah Public School. After leaving school, he became an apprentice baker and eventually worked at the Union Bakery in Port Pirie for many years. Ted grew up with eight brothers and sisters in a close-knit household. The family endured a heartbreaking series of tragedies in the early 1900s. In September 1901, Ted’s 17-year-old sister Ethel died suddenly of heart disease after a brief illness, her death causing shock in the Port Pirie community.

That same year, the Parhams also lost 19-year-old Hilda after the birth of her son Leonard, and only months later, in April 1902, their 12-year-old daughter Norah Ellen “Nellie” died of pneumonia. Newspapers noted the compounded grief, recording that three daughters had been lost within twelve months.

Ted grew up with his eight siblings in a close-knit household:

- Edgar (Ted) (1878-1916) KIA Fromelles

- Fannie (1880–1952) married Jonathan Charles Kurll

- Hilda (1882–1901) died aged 19

- Ethel (1884–1901) died of aged 17

- Myrtle (1886–1969) married Private Walter Edwards, 2104, 5th Pioneer Btn

- Norah Ellen (1889–1902) died of pneumonia aged 12

- Alice Mary (1893–1969) married William Edgelton Smart

- Norman Vivian (1896–1970) married Eileen Johanna Reynolds

- Leonard Cecil (1901–1963) (Hilda’s son who was raised by grandparents)

The family home at Rose Street, Prospect West, later became affectionately known as “Edgarville.”

In 1901, Ted married Ethel Mary Codd (1882–1956) at Port Pirie. Together they had three children

- Hilda May (1901–1973)

- Francis William (1903–1963)

- and Lilian Eunid (1905–1993)

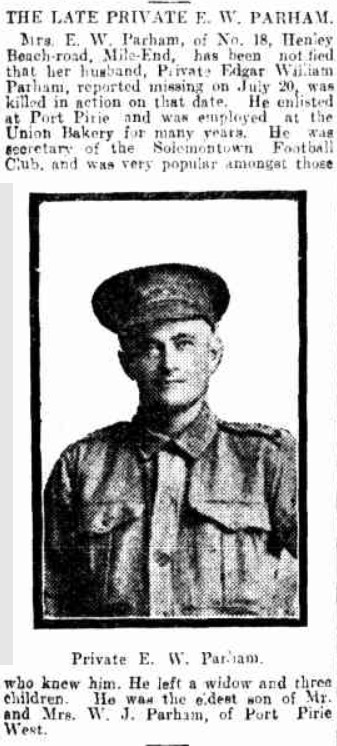

Ted was well known in Port Pirie for his involvement in the community. He served as secretary of the Solomontown Football Club and was described by friends as:

“very popular amongst his comrades here and esteemed by all who knew him”

Off to War

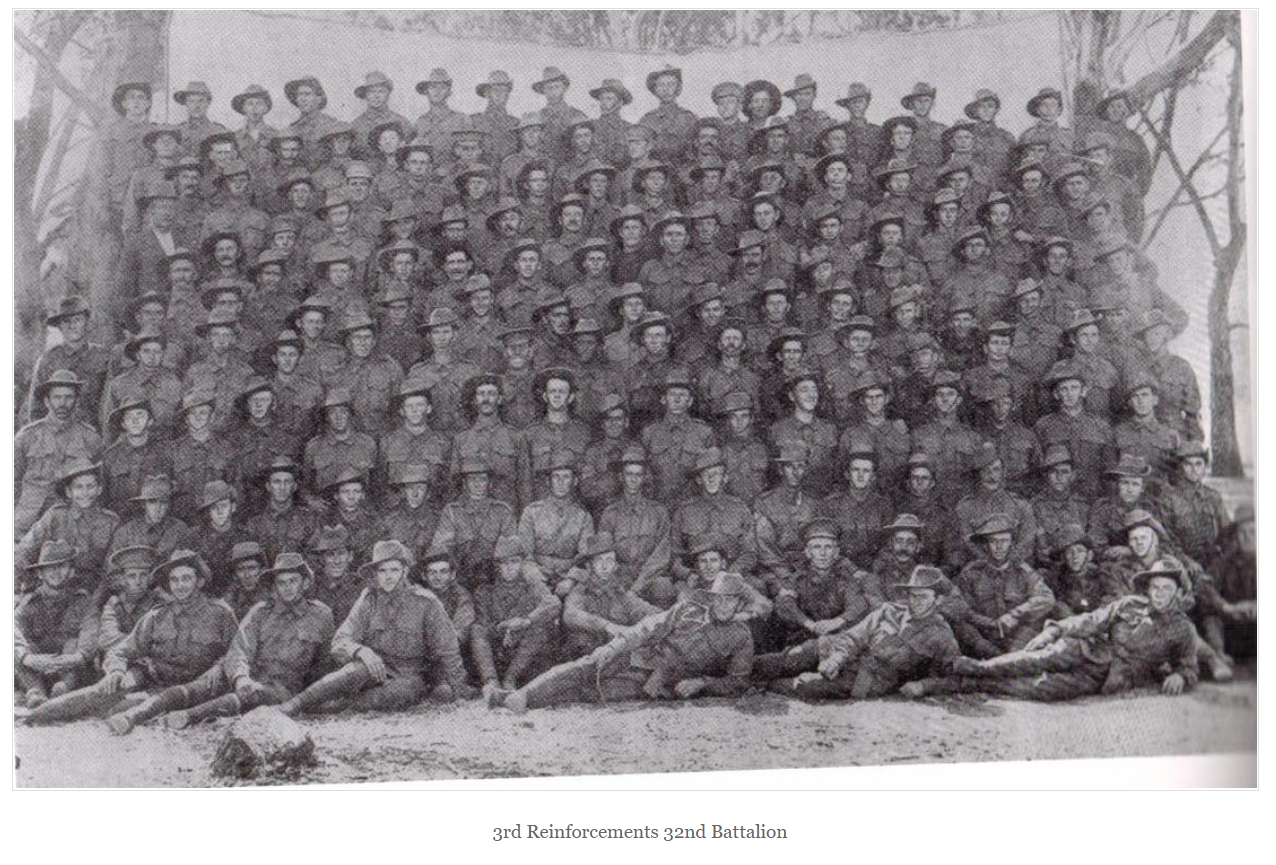

By the time Ted enlisted on 2 September 1915 at Adelaide, he was 37 years old, a married man with three young children and a well-known figure in Port Pirie. Motivated by the reports from Gallipoli and the national call to “help the boys,” Ted answered the call, joining the 32nd Battalion as part of the 3rd Reinforcements.

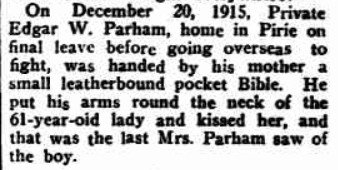

Before embarking, he visited his parents one last time at Port Pirie. His mother, Mary, gave him a small leather-bound Bible as a parting gift, inscribed:

““To E. W. Parham, No. 2092, from his mother. December 20, 1915"

In different handwriting, was written “Mother” and “Australia”

Ted embarked from Adelaide on 7 February 1916 aboard the HMAT A28 Miltiades. He trained in Egypt and was taken on strength at Duntroon Plateau on 1 April 1916, joining “B” Company of the 32nd Battalion.

The 32nd Battalion had been raised in South Australia and Western Australia in August 1915 as part of the 8th Brigade of the 5th Division. After training at Mitcham Camp in Adelaide, they embarked for Egypt. Through early 1916 the battalion moved between El Ferdan, Ismailia, and Tel El Kebir before marching to Duntroon Plateau and Ferry Post to guard the Suez Canal. Their final weeks in Egypt were spent at Moascar in May. One soldier’s diary captured life in the desert:

“sick up to the neck of heat and flies… dog biscuits and bully beef.”

In June the battalion left Alexandria aboard the Transylvania, arriving at Marseilles on 23 June 1916 before immediately entraining north to the Fleurbaix sector. Private Theodor Pflaum recorded the scenes as their train travelled through France:

“The people flocked out all along the line and cheered us as though we had the Kaiser as prisoner on board!!”

For many men, the change from the desert to the green fields of France was striking. Private Wesley Choat later wrote:

“The change of scenery in La Belle France was like healing ointment to our sunbaked faces and dust filled eyes. It seemed a veritable paradise, and it was hard to realise that in this land of seeming peace and picturesque beauty, one of the most fearful wars of all time was raging in the ruthless and devastating manner of 'Hun' frightfulness.”

The battalion moved into the front area on 14 July and occupied the trenches for the first time on 16 July, in preparation for an assault on the German lines opposite Fromelles. D Company’s Lieutenant Sam Mills wrote home with quiet optimism:

“We are not doing much work now, just enough to keep us fit — mostly route marching and helmet drill. We have our gas helmets and steel helmets, so we are prepared for anything. They are both very good, so a man is pretty safe.”

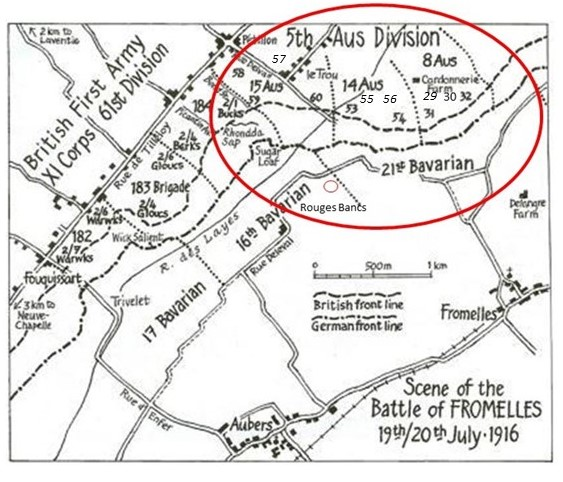

The Battle of Fromelles

Only weeks after arriving in France, the 32nd Battalion were rushed into battle at Fromelles on 19–20 July 1916 — their first action on the Western Front. The battalion moved to the front line on 14 July and entered the trenches for the first time on 16 July in preparation for the assault. D Company’s Lieutenant Sam Mills wrote home with optimism before the attack:

On 17 July, the men were out reconnoitering trenches and cutting passages through the wire, preparing for the attack, which was delayed due to bad weather. The 32nd Battalion, part of the Australian 8th Brigade, were tasked with crossing roughly 100 metres of No-Man’s-Land and attacking the German trenches on the extreme left flank of the Allied line. This position made their job even more dangerous, as they not only had to face the front defences but also protect their exposed left flank to prevent the Germans from working behind them. Private Frederick Stolz described the eerie calm before the battle began:

“The fellows were wonderfully cool and not during the whole time did I see anyone get excited or do anything silly, and such a lot were only young boys of between 18 to 20.”

By 5.45 PM on 19 July, all were in position. At 5.53 PM the first wave went over the parapet; A and C Companies led, with B and D — Edgar’s company — following in the third and fourth waves. The first lines moved into No-Man’s-Land and lay waiting for the British bombardment to lift. At 6.00 PM the order came and the German lines were rushed. The Australians faced devastating fire from German rifles, machine guns, and artillery.

Despite the losses, the 32nd succeeded in capturing the enemy’s first-line trenches by 6.30 PM. Fighting raged through the night as the men pushed toward the second line under relentless counter-attacks.

Private William Ludemann later remembered the conditions in the captured trenches:

“They flooded it and the chaps were up to their waists in water all night.”

At around 4.00 AM, German bombing parties attacked the 32nd from the left flank. With their rear trench under-manned and supplies running out, the Australians were quickly isolated. At 5.30 AM the Germans counter-attacked in force from both flanks, surrounding the 32nd and cutting off their retreat.

One private later told the Red Cross of the retreat across No-Man’s-Land:

“Men were coming back any way they could — crawling, carrying mates on their backs. There were dead and wounded all over the ground; I never want to see such a sight again.”

It was in this chaos that Ted was last seen. According to later reports, he was badly wounded and captured in the German trenches. As he lay dying, a German soldier knelt beside him, attempting to understand his final words. With the last of his strength, Edgar reached inside his tunic, pulled out the small Bible his mother had given him, and handed it to the soldier with the words:

“Here, Fritz, you had better take this.”

The 32nd Battalion suffered catastrophic losses: 718 casualties out of 800 men, including 90 percent of its front-line strength.

Ted was among those who never returned.

After the Battle

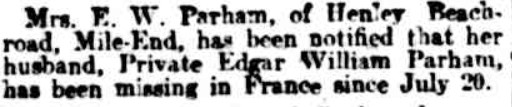

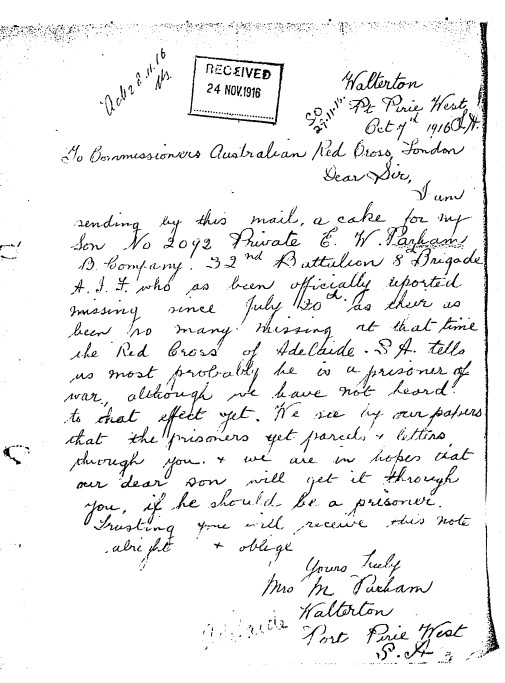

When roll call was taken after the attack at Fromelles, Ted was among the hundreds listed as missing. His wife Ethel, at Henley Beach Road in Mile End, received the first brief cable in late August 1916 advising that he was missing in France.

In October 1916, his mother Mary wrote to the Australian Red Cross in London in desperation:

“I am sending by this mail a cake for my son No. 2092 Private E.W. Parham, B Company, 32nd Battalion 8th Brigade A.I.F. who has been officially reported missing since July 20th. As there have been so many missing at that time the Red Cross of Adelaide tells us that most probably he is a prisoner of war… We see by our papers that the prisoners get parcels & letters through you, & we are in hopes that our dear son will get it through you, if he should be a prisoner.”

In February 1917, the South Australian Division of the Australian Red Cross Society wrote to his father, William James Parham, with the devastating news:

“We regret to state that this soldier’s name appears on the German death list of 4th November last. We understand that these death lists are made up from the discs gathered from the dead bodies of the soldiers… We sincerely regret that this is the only information we have been able to gather relative to your son, and take this opportunity of tendering our deepest sympathy.”

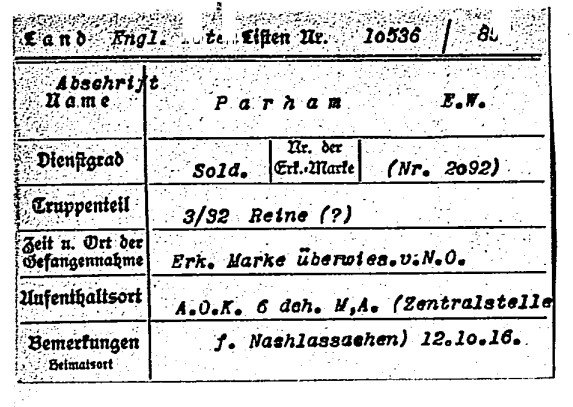

After the Battle, German authorities compiled lists of the Allied dead recovered from the battlefield. These were forwarded through the International Red Cross to London and became known as the “German Death List (GDL).” Ted’s name appeared on the list dated 4 November 1916, confirming he had died in the fighting near Fromelles. The GDL later became one of the key pieces of evidence in tracing the fate of the missing. The accompanying note confirmed his fate:

“austr. Sold. Parham, E.W. Nr. 2092. austr. Batt. 3/32 … gefallen in Gegen Fromelles, 19.7.16’.”

For his greiving wife and family, there would be clear outcome for many years. Ted’s body lay among the mass of the fallen left behind and buried by the Germans in pits behind the lines.

The Bible Returns Home

In the months and years after Fromelles, Mary and Ethel Parham could only hope that Ted might have been taken prisoner. What they did not know was that, in his final moments in the German trenches, Ted had given the small Bible his mother had inscribed to a German soldier.

The German soldier, later identified as Steinmetz, kept the Bible for twenty years, telling his family of the dying “English” soldier who had pressed it into his hands as he lay dying in the German trenches at Fromelles. Inside the cover, the flyleaf carried Ted’s service number and the words his mother had written before he left home:

“To E. W. Parham, No. 2092, from his mother. December 20, 1915.”

On the same page, Ted had added his own hand-written note with the words "Mother” and “Australia.

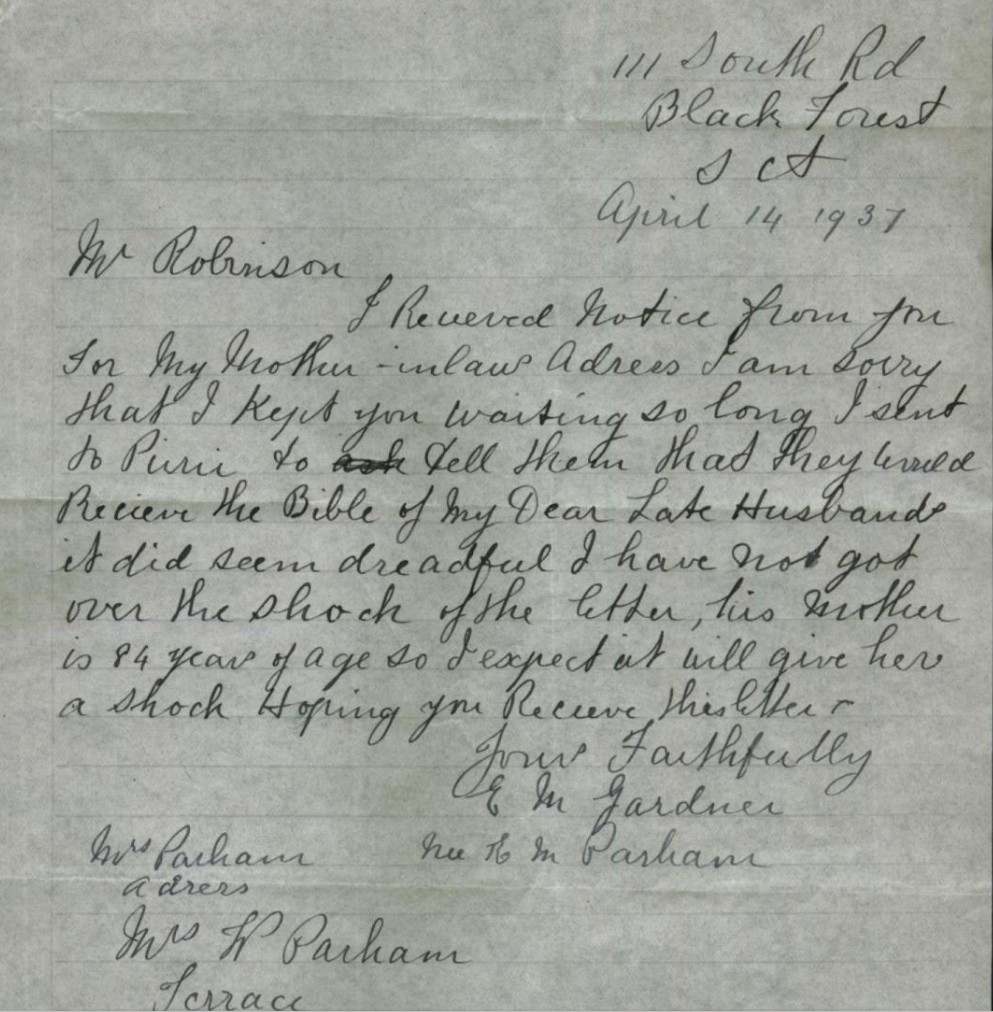

When Steinmetz himself lay dying in 1937, he asked his brother Karl to return the Bible to the soldier’s family. Karl passed it to the British authorities, who forwarded it via the Australian High Commissioner in London to Base Records in Melbourne. By this time, Ethel had remarried and moved, but when she received word of the discovery she wrote back in shock.

In April 1937, the Bible was finally returned to Port Pirie and placed into the hands of Ted’s 83yearold mother, Mary on her 83rd birthday— two decades after she had kissed her son goodbye and written her name in its flyleaf. When the Bible was finally returned in 1937, the Mary wrote to the Steinmetz family in Berlin, expressing her thanks for the compassion that had carried a dying soldier’s gift across two decades and two nations — a small act of humanity as the world edged toward another war.

Mary responded by inscribing another Bible and sending it to Karl Steinmetz with a message:

`“That young men would never again be sent out to kill and be killed.”

Ted’s granddaughter Barbara Henderson later described the returned Bible as :

“a family heirloom — it carries quite a story.”

Legacy

For more than ninety years, Ted lay among the missing of Fromelles. His name was carved on the VC Corner Memorial alongside hundreds of others whose bodies were never found. For his family, the small Bible returned in 1937 became both a relic and a reminder — a connection to their son, husband, and father who never came home. Ted’s wife Ethel raised their three children alone. She later remarried, but the memorial notices placed over the years show that she and the children never stopped remembering him:

“Time cannot fill the aching void,

nor from our memory tear

The face and form we loved so well,

and will dwell for ever there.

But God is good, and gives us strength to bear our heavy cross,

He is the only one who knows our loneliness and loss.”— Inserted by his loving wife and children, Rose Street, Prospect.

Ted’s loss reverberated through the Parham families for decades. The memorial notices they placed give a glimpse into their grief and love:

“In our hearts your memory lingers, Sweetly, tender, fond, and true; There is not a day, dear Eddie, That we do not think of you.”— Inserted by his loving father, mother, brothers and sisters.

PARHAM.—In loving memory of our dear father and grandfather, E. W. Parham, killed in action on 20th July, 1916. Loved by all.— Inserted by his loving daughter and son-in-law, grandchildren, Hilda, Joe, Dulice, Valma.

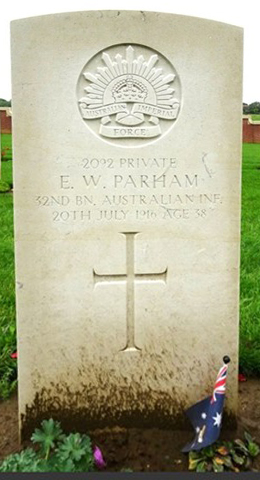

Ted is commemorated at:

- Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery – Plot I, Row D, Grave 11.

- Adelaide National War Memorial, South Australia.

- Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, Panel 121, Canberra.

- Port Pirie Fathers of Sailors and Soldiers Association District Roll of Honour WW1, Port Pirie, South Australia.

- Port Pirie Oval WW1 Memorial Gates, Port Pirie, South Australia.

- Prospect Roll of Honour A–G WWI Board, Prospect, South Australia.

- Mallala Reeves Plains State School Old Scholars Honour Roll, South Australia.

Finding Ted

Pheasant Wood Identification and Ceremony

For more than ninety years, the fate of the missing from the Battle of Fromelles remained unknown. Ted’s name was among the hundreds inscribed on the VC Corner Memorial, with no known grave. The breakthrough began with a single clue — a line in a Red Cross Wounded and Missing file noting a possible burial near Pheasant Wood. In the early 2000s, a dedicated team of researchers pieced together aerial photographs, German records and battlefield evidence, confirming the existence of mass burial pits behind the German lines at Fromelles.

In 2008, a limited excavation confirmed human remains. The following year, a full recovery uncovered the bodies of 250 Australian and British soldiers. In 2010, they were reburied with full military honours at the newly created Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery. At that time, the majority of the men were laid to rest under headstones marked “An Australian soldier of the Great War – Known unto God.”

It was not until 2014, after years of DNA matching and painstaking archival research, that Ted’s identity was confirmed. Nearly a century after his death, Ted finally had a named grave: Plot I, Row D, Grave 11. On 19 July 2014, a special dedication ceremony was held to unveil the newly named headstones at Pheasant Wood. Bruce Pointon, who researched the Parham family and wrote a dedicated book on Ted, attended the service:

“The story surrounding this Bible and the intriguing chain of events that saw it returned in 1937 to 83-year-old Mary Parham is unique and very moving. It is unbelievable to think it got through that very narrow channel. I was thrilled to be able to complete Ted Parham’s unfinished story. It is such a remarkable one.”

Today, his grave carries his name, age, battalion, and the words

“Known to his family as Ted — a loving husband and father.”

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).