Clark Maxwell GRAY

Eyes dark grey, Hair dark brown, Complexion dark

Clark Maxwell Gray – Dunedin’s finest

With appreciation to Malcolm Mathias for his persistent search efforts into Max’s background and his contributions to this story. Malcolm has been the newsletter Editor for the Friends of the 15th Brigade and is the custodian of the 58th Battalion Banner which he has carried during the annual ANZAC Day marches. Thanks also to Scotch College Melbourne and the East Melbourne Historical Society for information relating to Clark Maxwell Gray.

Early Life

Clark Maxwell Gray, ‘Max’, was born on 6 December 1896 in Dunedin, New Zealand to William and Mary (nee Cameron) Gray. Max was the eldest of their three sons. His brothers were Alastair Cameron, born in 1896, and Hugh Stewart in 1902.

Max attended the Terrace Primary School in Thornton, Wellington and then Wellington College from 1909-1911. He was in the Cadets and was Sergeant in charge of the platoon that won a public-school competition for Senior Cadets. Max was also a King’s Scout.

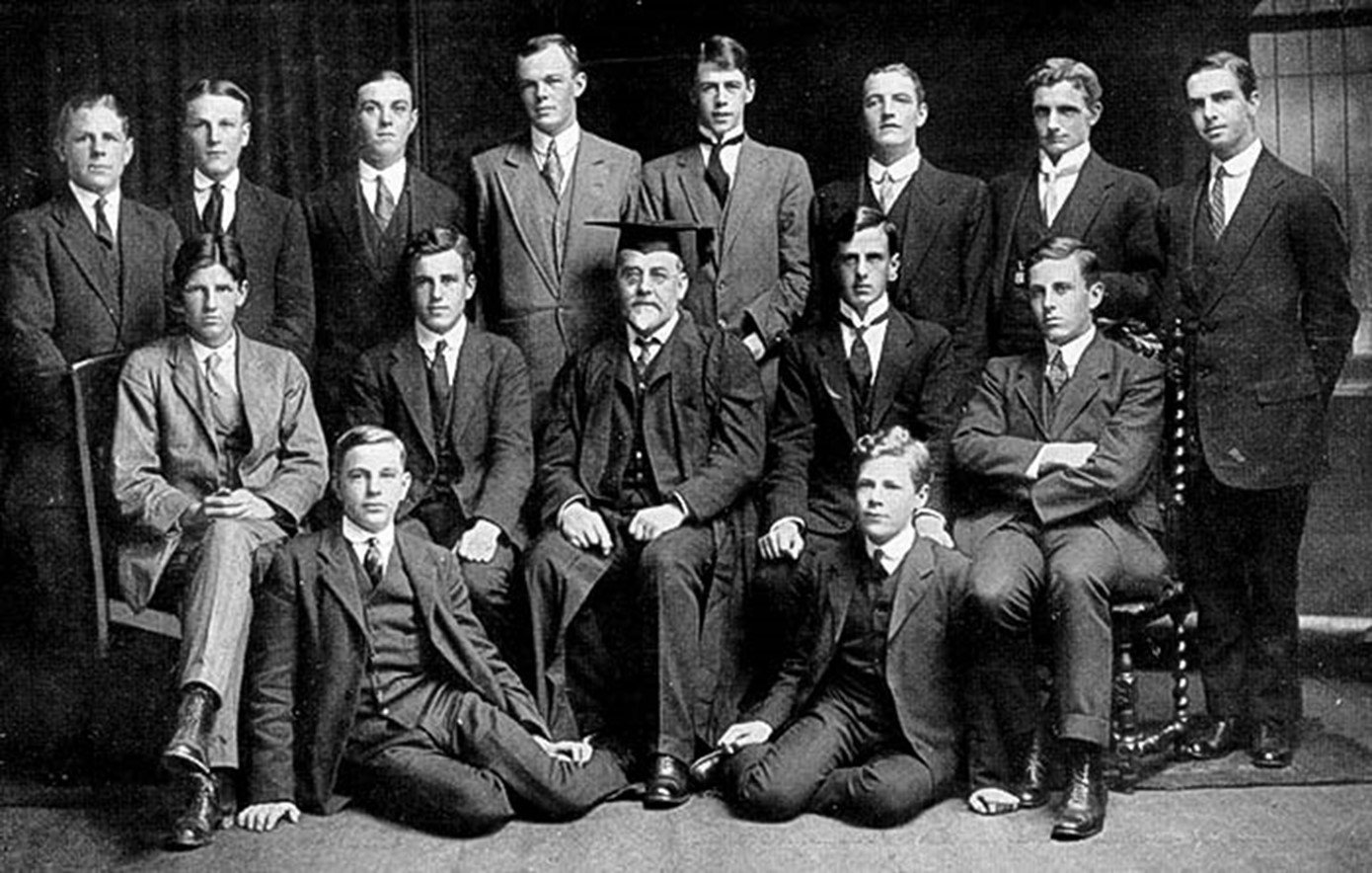

In 1911, when Max was 15, the family moved to Melbourne, Australia, because his father took the position as Principal, Presbyterian Ladies College.Max attended Scotch College from 1912 to 1915. His leadership skills were demonstrated at this early age, becoming a Prefect in 1914 and 1915.

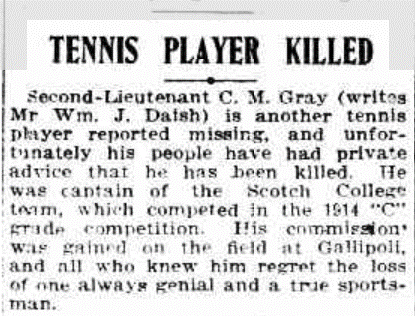

He won several academic prizes, including an Ormond residential scholarship, and was an avid tennis player, playing for the Scotch College seconds. Also, as he had done in New Zealand, he served for two years in the Senior Cadets.After graduation, he briefly attended the University of Melbourne and was planning to study medicine. However, after only for a short time he answered the ‘Call to War’.

Max’s brother Alastair also enlisted (No. 37596), in November 1917. He served in Europe and returned to Australia in March 1919.Back home, Alastair trained as an Architect and was a teacher and an artist as well. His paintings were exhibited around the world and are held in numerous national galleries. His wife was a well-known female Australian tennis champion. They had one son, Ian, who became a Supreme Court Justice. Hugh studied as a Dentist and eventually moved to England. He signed up for the RAF in 1939 and served in the Dental division. He died in 1972 in Wycombe, England.

Off to war - Gallipoli

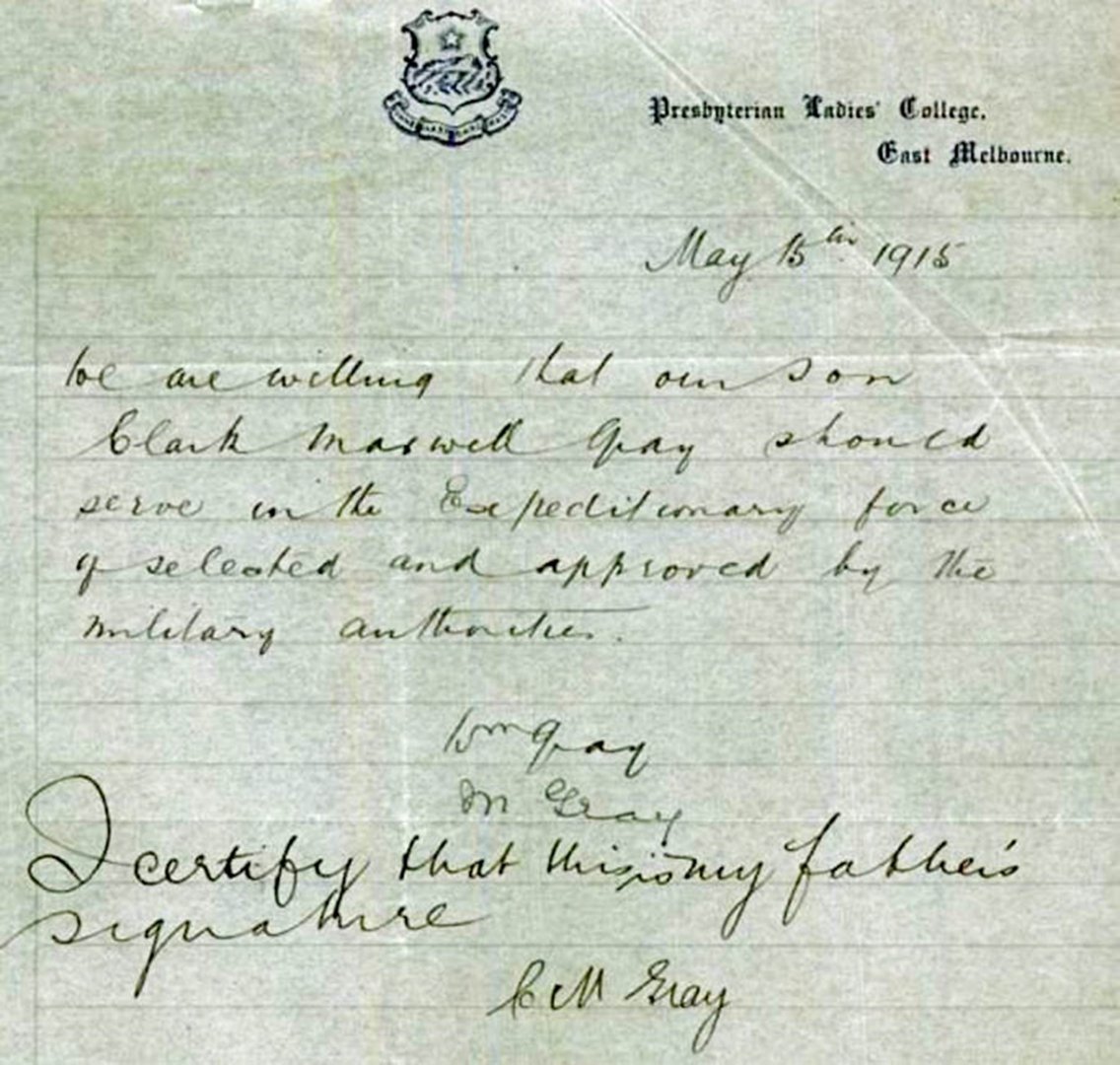

Max enlisted on 31 May 1915 and was assigned to the 6th Battalion, 7th Reinforcements.As he was underage, his parents had to give him written permission to enlist.

After a very short period of military training at the Seymour Camp, Max embarked from Melbourne aboard HMAT A64 Demosthenes on 16 July 1915, headed for Egypt, a journey of about a month.Soon after arriving, he was sent to Gallipoli and joined with 6th Battalion on 5 September 1915.

While the major battles were over by this time, there was still plenty of ‘action’ going on.He wrote a vivid letter about his experiences. His arrival at night, swimming amidst enemy shellfire (and enjoying it), how the miles of Anzac defences were ‘like ground bored by rabbits’, the ominous onset of winter rain, and matter-of-factly explained how a bullet had struck his temple but, as it was spent, inflicted only a bruise.

He obviously demonstrated his leadership skills, being promoted to Temporary Sergeant on 1 October 1915. While he was later reverted to Private, he was then formally promoted twice within a short time, to Corporal in November and to Lance Sergeant in December.The 6th left Gallipoli in mid-December as part of the general evacuation, arriving in Alexandria from Lemnos on 7 January 1916.

Egypt

After the major losses at Gallipoli and the influx of recruits from Australia, major reorganizations were underway. Max was transferred to the newly formed 58th Battalion in February. Roughly half of its recruits were Gallipoli veterans from the 6th Battalion and the other half were fresh reinforcements from Australia.

Max’s promotions continued – to Sergeant on 15 January 1916 and to Second Lieutenant on 16 March. An impressive rise for a 20-year-old.After a month of training at the large camp at Tel el Kebir, they had a two+ day, 50 km march in thermometer-bursting heat across the Egyptian sands from Tel el Kebir to Ferry Post, near the Suez Canal. Prior to marching, only ½ pint of water per bottle was available.

Source: AWM4 23/15/1 15th Brigade War Diaries Feb-Mar 1916 p 6

By early June the Battalion was at a total strength of over 1000 men and in mid-June orders came to head for the Western Front. On 17 June they went to Alexandria to board the H7 Transylvania.

To the Western Front and Fromelles

The 58th disembarked in Marseilles 23 June 1916. From there they had a three-day train ride to Steenbecque, 35 km from Fleurbaix.After marching to Fleurbaix and undergoing further training, including the use of gas masks, they were into the trenches for the first time on 11th July.

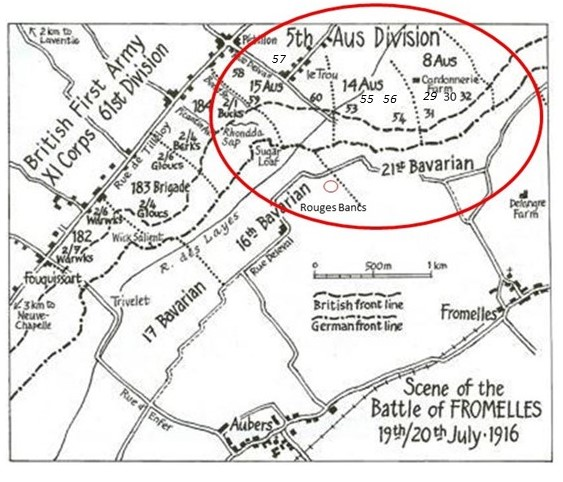

The battle plan had the 15th Brigade located just to the left of the British Army. The 59th and 60th Battalions were to be the leads for this area of the attack, with the 58th and 57th as the ‘third and fourth’ battalions, in reserve.The ‘Sugar Loaf’ salient, a heavily manned position with many machine guns, was directly across from them. Fire from here could enfilade any troops advancing towards the front lines, giving the Germans a significant advantage. In his memoirs, a fellow soldier of the 58th, Bill Boyce (3022) summed the situation up well for what many of the soldiers must have been thinking, ‘What have I let myself in for?’

Source: Australian War Memorial Collection C386815

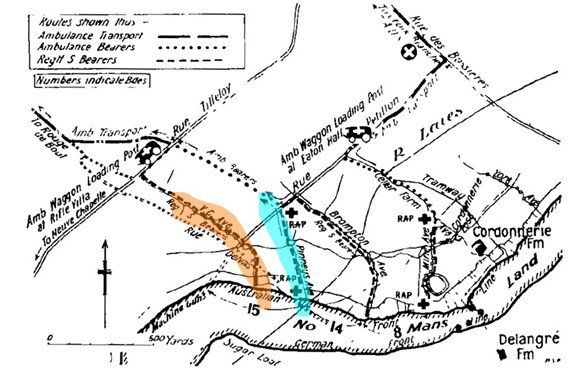

The 58th Battalion’s role was to be carrying ammunition, digging the communication trenches for area gained in No Man’s land and to be into battle for fighting, as needed. Max was in charge of the ammunition supplies for his unit.The Australians’ attack was planned for the 17th, but it was delayed due to bad weather.

They were back in position for the attack on 19 July and the 59th and 60th went over the parapet at 5.45 PM, with immediate and intense fire from rifles and the Sugar Loaf machine guns, just a short distance away. As documented in the messages sent back to HQ just after the attacks began:

“cannot get on the trenches as they are full of the enemy”

“every man who rises is shot down”

“they were enfiladed by machine guns in the Sugar Loaf and melted away.”

Source: AWM4 23/15/5 15th Brigade War Diaries July 1916 p 78, p56

While the 58th were not directly in the initial attack, it was still a dire situation. Bill Boyce said –

‘…although it was dark, they had lights going up, and coming down. They turned machine guns on and artillery fire as well and the only thing you could do was just lay yourself flat on the ground until the worst of it was over…’

Source: Conversations between Bill Boyce and Lambis Englezos September the 5th 1992

Max’s A Company were called in for fighting support at 9.30 PM, but the conditions had not improved from the initial charge by the 59th and 60th:

“move across open ground and fire trenches & charge at 10 PM.

”“Heavy losses”

“Unable to evacuate dead or wounded."

Source: AWM4 23/75/6 58th Battalion War Diaries July 1916 page 10

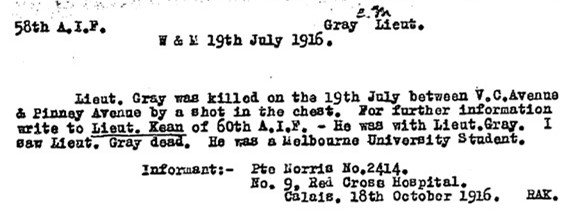

Witnesses after the battle said Max was between VC Avenue and Pinney Avenue, directly across from the ‘Sugar Loaf’ guns.

By 6.00 AM the next morning, the 58th were out of the trenches and were relieved by the 57th. Max was not at roll call.Of the 1002 men of the 58th that left Egypt, the initial roll call reflected 27 killed, 167 wounded and 53 missing. Ultimately the impact was that 154 soldiers were killed or died from wounds. Of this total, 64 remain missing/unidentified. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large amount of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield.

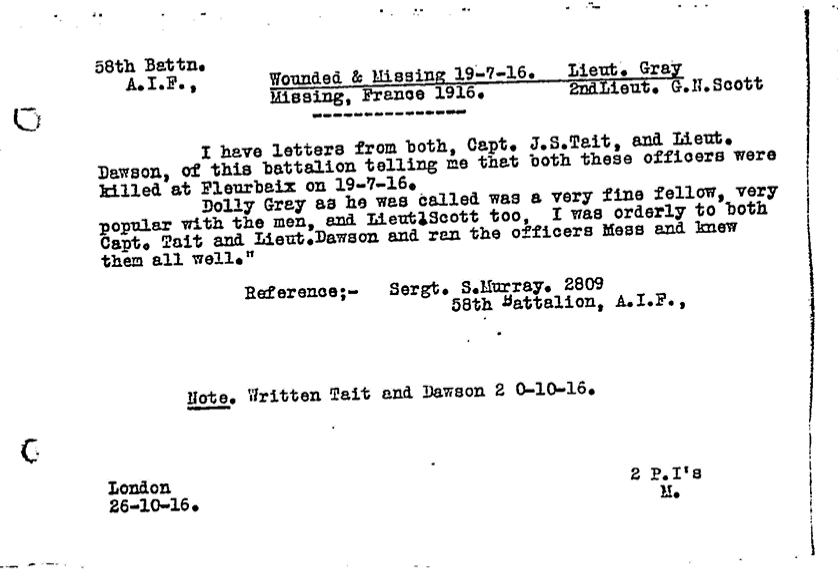

Max’s Red Cross Wounded and Missing file contains numerous statements about his fate. Given the battlefield confusion, some are contradictory.Max was most likely killed by machine gun fire in No Man's Land. Other accounts say that he was shot in the chest, hit in the thigh and stomach and taken prisoner.

Captain J.S. Tait said Max was ‘among those who gave up their lives on that day’.

Source: Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Files – Clark Maxwell Gray p 12

A statement from Sergeant S. Murray (2809) said that Max was commonly called ‘Dolly Gray’ (from a popular song) and that he was ‘a very fine fellow’ and ‘popular with the men’.

Statement, Red Cross File No 1201004, 4535 Pte O.C. LAIDLER, C Company, 58th Bn (patient, Faucett Road Hospital, Portsmouth, England), 4 December 1916:

'Informant states that in July 1916 at Fromelles during a raid on the German trenches Lt. Gray was taken prisoner. Informant had been told this by Private Gordon, A. Coy., 58th Battn., A.I.F. who was with Lt. Gray during the raid, but Informant could not say for certain that Pte. Gordon had seen [underlined] Lt. Gray taken prisoner though he understood that he had done so.'

2414 Pte J.R. NORRIS, 58th Bn (patient, No 9 Red Cross Hospital, Calais), 18 October 1916:

'Lieut. Gray was killed on the 19th July between V.C. Avenue & Pinney Avenue by a shot in the chest... I saw Lieut Gray dead. He was a Melbourne University Student.'

1774 Pte G. JAMES, C Company, 58th Bn (patient, No 2 General Hospital (Palais), France), 5 December 1916:

'At Fromelles on 19th July about 6 p.m. we had attached the German first line and been driven back. I was with Lieut. Gray: on our way back to our trenches I saw him hit in the right thigh and stomach. I had to carry on. Next day I saw Lt. Keyes 57th Battn. Trench Mortars and he told me he had been out with a search party early next morning and found Lt. Gray's body and he brought in all his belongings.'

Statement, Red Cross File No 1201004, 2603, Pte Cameron wrote:

“Informant says Lieut. Gray was in charge of Grenadiers in July 19th in attack. Only one of them came back and he stated Lieut. Gray had been killed. Informant does not know the survivors name that brought the news. The position attacked by Lieut. Gray remains in German hands.”

No truce was declared after the battle, so soldiers’ bodies were unable to be recovered.Max was formally declared as ‘Killed in Action’ on 6 August 1916.

Red Cross reports did note that his personal effects were recovered from his body by a search party on the next morning. Two discs (presumably his ID tags), a star, his wallet and photos were returned to the family in November 1916, so there was some closure for the family.

After the Battle

About a month after his death a fellow officer of the 58th, Lieutenant William Scurry wrote a letter that was reproduced in Gray’s The Scotch Collegian obituary:

’You will know by now that Max has paid a soldier’s big price, and that you are left with all the pride that he was an officer and a gentleman…. Think of all I know of him. We lived together out there on the scorching sand; we swam, rode and talked together, and always I was the gainer by our friendship. When last I saw him as I stood among my guns on that evening, he gave us another lesson which I and a lot of my comrades will gain by.

There was not one of his men in front of him. Then later on in the night, as we still stood among those guns, we heard that somewhere in the front he had dropped, and still there were none of his men in front of him. He died, as, if it is so decreed, we would all choose to die, in front of his men and facing East.’`

Lieutenant George Wood, former Scotch teacher who also served in the 58th Battalion, wrote to the school in 1917 that among the many Scotchies and other servicemen he was meeting on the Western Front, ‘C.M. Gray, of the P.L.C., was very highly spoken of, both as a good fellow and as a good officer’.

Lieutenant George Wood, former Scotch teacher and a 58th Battalion officer, wrote to the school in 1917 that among the many Scotchies and other servicemen he was meeting on the Western Front, ‘C.M. Gray, of the P.L.C., was very highly spoken of, both as a good fellow and as a good officer’.

Source: https://www.scotch.vic.edu.au/greatscot/2016aprGS/16.htm

A short life, gallantly lived.

Max was awarded the Star, British War and Victory medals, a Memorial Scroll and Memorial Plaque. He is commemorated at V.C. Corner (Panel No 13), Australian Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles and on panel 165 in the Commemorative Area at the Australia War Memorial, Canberra.

Brother - Alastair Gray

On 9 November, 1917, Alastair, a Gunner, embarked from Melbourne on th HMAT Port Sydney A15 , disembarking at Suez on 12 December the same year. By 22 December he was admitted to the 19th AGH in Taranto, then moved the UK for hospitalisation where he remained until 13 March 1918. On 13 April 1918 he sailed from Southampton to France where he joined the 12th Army based near Roulles. By 21 June he was hospitalised again for a week then sent to the 2nd Army Rest Camp in France for 2 months.

He rejoined the 47th Battalion mid-August, disembarking from France to Folkestone on 10 November, 1918, where again he was admitted to hospital for a week before sailing back to Australia mid-March 1919 on the' Port Denison'.

On return to Melbourne, Alastair trained as an Architect. He was a teacher and artist as well. His wife was a well known female Australian tennis champion. They had one son, Ian who became a Supreme Court Justice. Alastair was primarily a watercolor artist who also painted in oils. He was secretary of the Victorian Artists’ Society in 1958. Alastair’s paintings were exhibited around the world and are held in numerous national galleries. Alastair later remarried and died in 1972.

Brother - Hugh Gray

Hugh studied as a Dentist, eventually moving to England. He signed up for The RAF in 1939 and served in the Dental division. He died in 1972 in Wycombe, England.

A Quest to Know Your Ancestors Who Fought

On Sept 5, 1985 Malcolm Mathias enjoyed a very reflective family history conversation with his mother Grace. Malcolm asked Grace about her childhood with her grandparents and if Grace knew anything about her father. Grace said that she had asked her grandmother about her father when Grace was quite young, about 6 or 7 years old (Circa 1920/21). Her grandmother said, “I don’t know and your mother said it doesn’t matter anyway, he was killed in the war.”Malcolm has said, “It still matters to me.”Malcolm‘s curiosity was piqued by this and he engaged a military historian to look at the Victorian Army records and Malcolm dug into what records he could find. Some possible links to Max were noted, but nothing conclusive was uncovered.In any case, Max is truly honoured by Malcolm’s interest and persistence.

Can Max still be found?

On 19 July, 1916, the AIF was engaged in the Battle of Fromelles, its first on the Western Front. Max was likely killed instantly in No Man's Land sustaining machine gunshots to his arm and stomach whilst delivering ammunitions. Initially there was some thought he had been taken prisoner by the Germans, however several eye witness accounts confirmed he was killed in action. Gray’s Red Cross Wounded and Missing file contains the usual contradictory rumours about his fate.

The Germans dug a mass grave at Pheasant Wood, near Fromelles, which contained 250 Australian soldiers’ bodies. This was discovered in 2008 and as of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been successfully identified by DNA testing. Genealogical research has been ongoing to find living relatives of the remaining 70 unidentified soldiers.There was a total of 937 soldiers from the 15th Brigade who were killed, of which 623 were missing. Only three of the missing soldiers have been found to be in the Pheasant Wood grave.It is only a slim hope that Max could still be found, but one worth pursuing.

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).