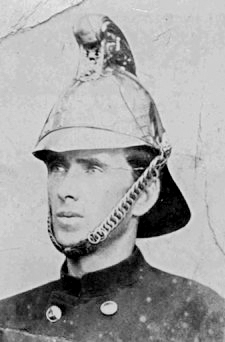

Milton James Leslie MORRISON

Eyes dark blue, Hair dark brown, Complexion medium

Milton Morrison – From Kangaroo Creek NSW to the Fields of Fromelles

Can you help find Milton?

Milton James Leslie Morrison’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial. A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing. Milton James Leslie may be among these remaining unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in Narrabri, NSW. See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family. If you know anything of contacts for Milton James Leslie, please contact the Fromelles Association. Please contact the Fromelles Association of Australia to find out more.

With thanks to Milton’s nephew Colin Morrison for all of his input for this story.

Early Life

Milton was born on 27 April 1894 at Deep Creek, Narrabri, New South Wales, the second child of James Addison Morrison (1867–1949) and Vida Blanche Marian Brown (1864–1900). His birth was recorded at 2:20 am on the family’s small farm.

The family :

- Harold 1891-1953 (half sibling)

- Milton 1894-1916 - KIA Fromelles

- Cleveland 1896-1971

- Coralie (Coral) 1897-1976

- Wilfred K 1900-1904 - died Moree

Tragedy struck when Milton’s mother died in March 1900, leaving behind four children under ten years old — Harold, Milton, Cleveland, and Coralie — and a newborn, Wilfred, who died age 4. Their father, James, was unable to provide for them and soon returned to Newcastle. On 4 June 1900, the children aged 11, 7, 6, 3, were committed as wards of the state, including baby Wilfred. James continued to support himself. He remarried in 1908. The ward registers show that the Morrison children were kept together as much as possible, moving between foster homes and government depots.

Their earliest placement was with A. Cochrane at Castle Farm, Castle Doyle near Armidale, before short periods at the Maitland and Parkesbourne depots. By 1902, they were placed in Goulburn, where they spent several years, boarding with families such as the Warnes and the McCallums. Young Wilfred died in Moree in 1904. Over time, the children were shifted again — to Middle Arm, Glenreagh, Coffs Harbour, Albion Park, and Taree.

These constant relocations marked their childhood, but the records make clear that the siblings stayed together throughout, a rare circumstance for wards of the state at the time. Among the families they encountered, the Snodgrass family of Rocky Creek became especially important. Leicester Curzon Snodgrass, a local schoolteacher, later acted as executor of Milton’s will, while Edith McLachlan, connected to the Snodgrass circle, was named as one of his beneficiaries. These choices underline the strength of the bonds formed in childhood, at a time when the Morrison siblings had little else to rely on.

In 1908, James married Mary Kate Murphy (1883–1975) at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, Merewether. Three more children were born into family — Winifred Jean (1908–1940), Patrick Charles (1911–2001), and Francis Addison (1914–1972), but it is unlikely they knew of their older siblings. While James established a stable home in Merewether, Milton and his older siblings were already making their own way. By his late teens, Milton was working as a farm labourer at Kangaroo Creek, near South Grafton.

This rural setting placed him in the heart of the Clarence River farming district, a community that would later inscribe his name on the South Grafton Cenotaph. Coralie married George McCarthy in 1916.

Off to War

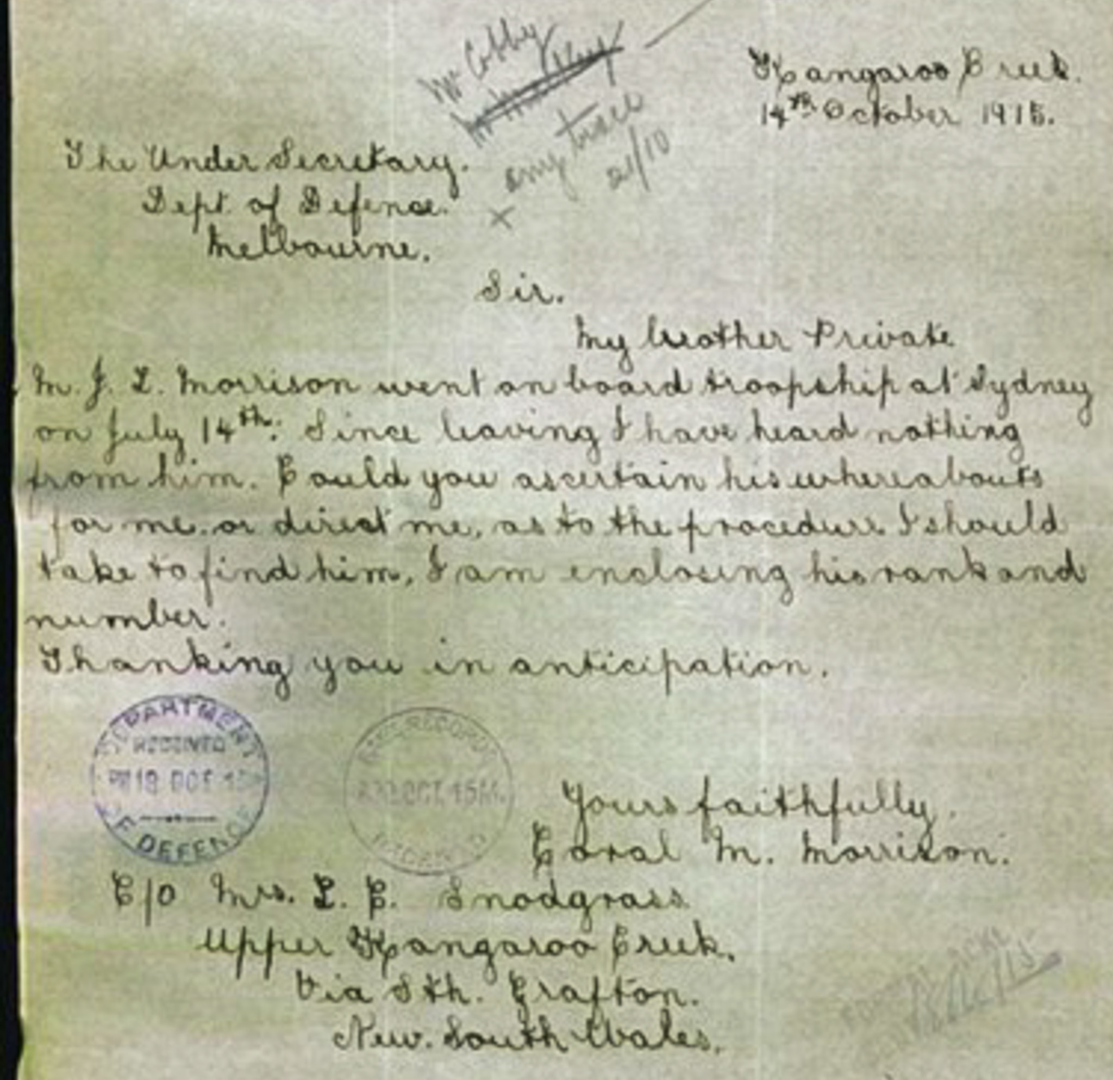

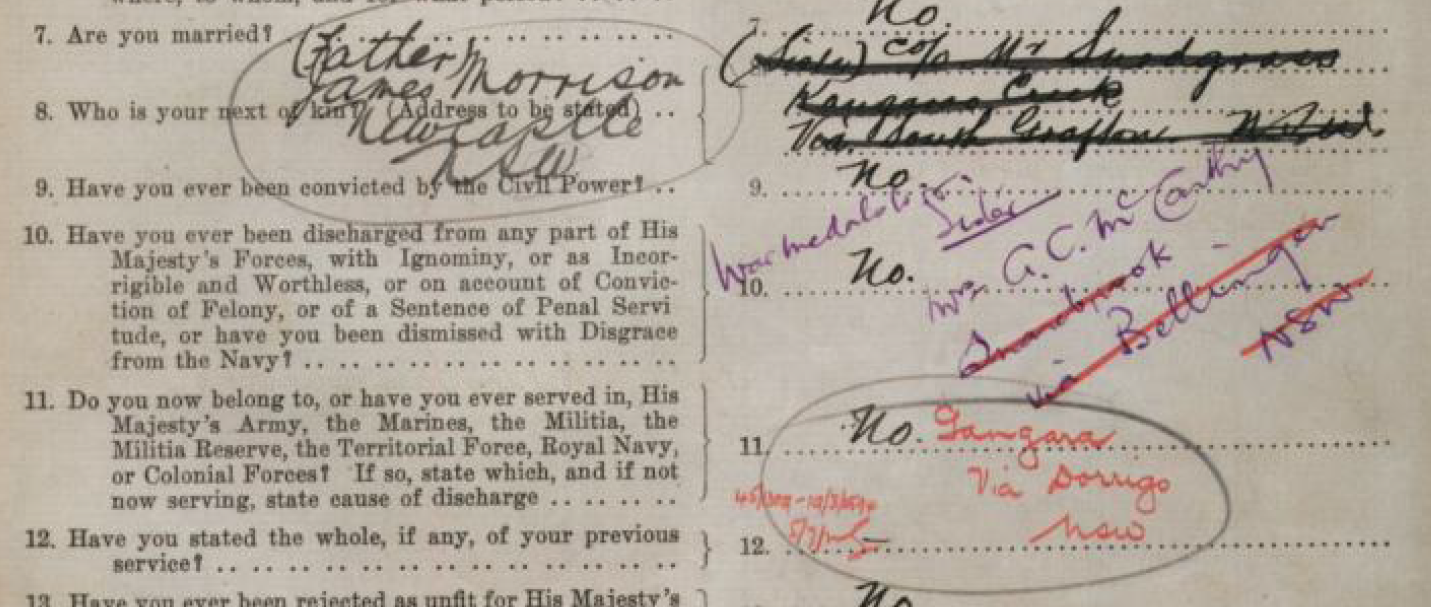

Milton enlisted at Liverpool, New South Wales, on 28 May 1915, just weeks after his 21st birthday. He was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 7th Reinforcement and was described as a small, but wiry man. Milton embarked from Sydney aboard HMAT A67 Orsova on 14 July 1915, headed for Egypt. His sister Coralie, still a teenager but yet his next of kin as Milton’s father’s whereabouts were unknown, was already checking on him in October 1915.

She was taking her responsiblity very seriously - as she may have done through the State Ward years, perhaps still under their jurisdiction, but supported by the teacher, Mr Snodgrass. In 1915, it is likely that the Morrison children were still closely in touch with Leicester Snodgrass, his wife and family.

Four days after she wrote the letter, Milton was boarding a ship in Alexandria headed for Gallipoli. He joined his unit on 4 November 1915. While snipers and shelling were ongoing, there were no major incidents. Milton returned to Alexandria on 28 December 1915 and presumably to the major camp at Tel-el-Kebir. With the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five, major reorganisations were underway.

The 53rd Battalion was formed on 16 February 1916 and was made up of Gallipoli veterans from the 1st Battalion and the new recruits from Australia. The Gallipoli soldiers in the 53rd were not slow in pointing out to whoever would listen that they were the “Dinkums” and the new recruits were the “War Babies”. Source:: AWM4 23/70/1, 53rd Battalion War Diaries, Feb-July 1916, page 3

Training in Egypt was arduous. In March, the men endured a three-day route march to Ferry Post, each carrying a pack, rifle, and 120 rounds of ammunition across soft desert sand in searing 38°C heat. “It was a significant challenge,” the brigade history recorded, though the march ended with a welcome swim in the Suez Canal.

In May, the battalion moved to Katoomba Heights Camp near Tel-el-Kebir, where they undertook intensive musketry and bayonet training. The men also drilled in replica trench systems built to resemble the German defences they would soon face on the Western Front. On 16 June when they began the move to the Western Front. 3 2 officers and 958 soldiers of the 53rd left Alexandria on 19 June on the troopship HMT Royal George, bound for Marseilles, France to become part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front.

They arrived in Marseilles on 28 June and immediately entrained for a 62-hour journey north to Hazebrouck before finally marching into the camp at nearby Thiennes in northern France. During their trip it was noted that their ‘reputation had evidently preceded them’, as they were well received by the French at the towns all along the route.

Source: AWM4 23/70/2 53rd Battalion War Diaries February - June 1916, p. 4

This area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. On 10 July, the 53rd entered trenches for the first time. The front near Fleurbaix was anything but calm. Rain flooded the communication trenches, artillery fire harassed supply lines and the soldiers dug in amid the mud and barbed wire of No-Man’s-Land.

The Battle of Fromelles

The men knew something was coming. They rehearsed attacks in replica trench systems, inspected bayonets, and watched as huge guns rolled into place behind the lines. Then on 16 July, they moved up for an attack—only to have it postponed due to weather. The delay proved torturous. Private Jim Granger (4784), a young Dorrigo soldier, described the tension in his dugout:

“We were held in suspense for three days… like a criminal waiting to hear the verdict. We had no dugouts where we were in the supports and shrapnel was bursting all round.”

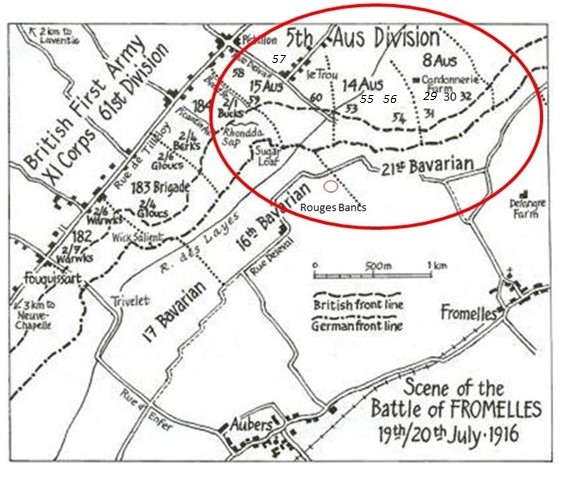

On the 19th, heavy bombardment was underway from both armies by 11.00 AM. At 4.00 PM the 54th Battalion rejoined on their left. All were now in position for battle. Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. The main objective for the 53rd was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines.

If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the 53rd and the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfiladed fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 60th and 54th Battalions on their flanks. The Australians went on the offensive at 5.43 PM. They moved forward in four waves – half of A & B Companies in each of the first two waves and half of C & D in the third and fourth.

They did not immediately charge the German lines, they went out into No-Man’s-Land and lay down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift. Private Arthur Crewes (4755) wrote of the time:

“At 5.43 pm the signal for the charge sounded, and over the top we went into the face of death, shells bursting, machine guns rattling and rifles crackling.”

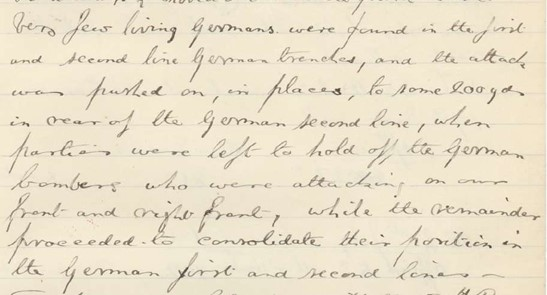

At 6.00 PM the German lines were rushed. The 53rd were under heavy artillery, machine gun and rifle fire, but were able to advance rapidly.

Corporal J.T. James of C Company (3550) reported:

“At Fleurbaix on the 19th July we were attacking at 6 p.m. We took three lines of German trenches”

The 14th Brigade War Diary notes that the artillery had been successful and “very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches”, but within the first 20 minutes the 53rd lost ALL the company commanders, ALL their seconds in command and six junior officers.

Source: AWM C E W Bean, The AIF in France, Vol 3, Chapter XII, pg 369

Some of the advanced trenches were just water filled ditches, which needed to be fortified by the 53rd to be able to hold their advanced position against future attacks.

They were able to link up with the 54th on their left and, with the 31st and 32nd, occupy a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm, but the 60th on their right had been unable to advance due to the devastation from the machine gun emplacement at the Sugar Loaf. They held their lines through the night against “violent” attacks from the Germans from the front, but their exposed right flank had allowed the Germans access to the first line trench BEHIND the 53rd, requiring the Australians to later have to fight their way back to their own lines.

By 9.00 AM on the 20th, the 53rd received orders to retreat from positions won and by 9.30 AM they had “retired with very heavy loss”.

Source: AWM4 23/70/2 53rd Battalion War Diaries July 1916 page 7

Of the 990 men who had left Alexandria just weeks before, the initial count at roll call was 36 killed, 353 wounded and 236 missing.

“Many heroic actions were performed.”

Source: AWM4 23/70/2 53rd Battalion War Diaries July 1916 page 8

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The final impact of the battle on the 53rd was 245 soldiers were killed or died from their wounds and, of this, 190 were not able to be identified.

After the Battle

When the guns fell silent at Fromelles, Milton was one of hundreds of men from the 53rd Battalion listed as missing. His name appeared in the casualty rolls, but his fate remained unclear to the authorities and his family. There are no mates who saw him wounded or dead and no Red Cross reports about his death.

In the weeks that followed the battle, the military authorities struggled to trace his next-of-kin, whom he had listed as his father, not his sister.

On 2 September 1916, Sydney newspapers carried public notices:

“The military authorities state that the following soldiers have been reported as casualties, but they have been unable to trace their next-of-kin: No. 2451, Private M. J. L. Morrison…”

The same day, The Daily Telegraph also published his name among those whose next-of-kin could not be found. The need for the public appeal reflected a deeper truth — the Morrison childrens’ fractured family circumstances. While Milton’s father was not responding, both his sister Coralie and friend Leicester Snodgrass were in regular contact with Base Records about Milton, which continued over the years:

- October 1916: Snodgrass enquired if any belongings had been received.

- July 1917: Snodgrass wrote, “As I hold a will of his appointing me his executor would you be good enough to inform me if anything has been officially heard of him …”

- July 1917: Coralie herself wrote from Hernani, near Armidale - “On the 19th July 1916, No. 2451 Pte. M. J. L. Morrison … was reported missing. Since then I have heard nothing … hoping you can tell me something.”

Milton was officially recorded as having been Killed in Action on 19 July 1916, from an Enquiry in the Field that was held on 2 September 1917. As a soldier who served overseas and was killed in action, Milton was entitled to the standard First World War campaign medals:

- 1914–15 Star – awarded to men who enlisted and served in a theatre of war prior to the end of 1915. Milton embarked on 14 July 1915 with the 1st Battalion, so he qualified.

- British War Medal 1914–20 – awarded to all members of the AIF who served overseas.

- Victory Medal 1914–19 – awarded to all members of the AIF who entered a theatre of war.

Together, these are often called “Pip, Squeak, and Wilfred” by collectors. Family records confirm the medals stayed with the Morrison family, however only one original medal is now know to the family.

Next of Kin?

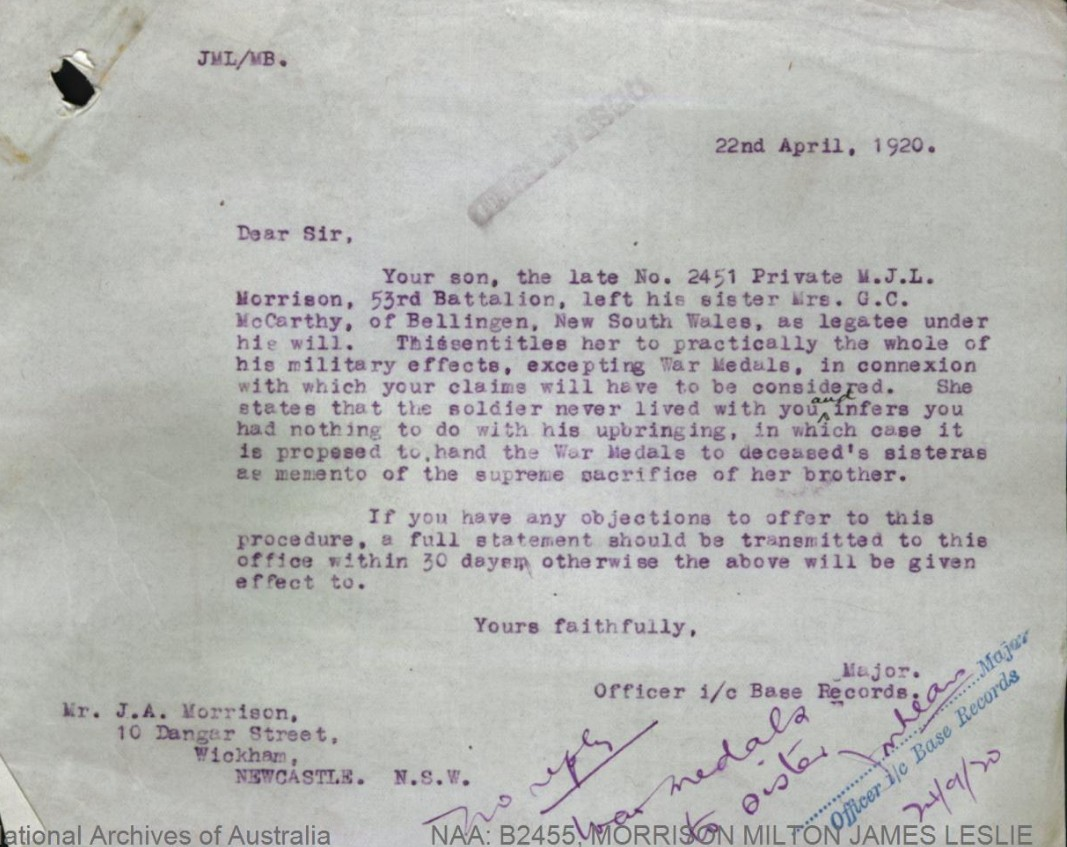

While there were enquiries about finding Milton’s father / next of kin in the 1916 newspapers based on what Milton had used in his enlistment papers, there are numerous communications from Coralie and Leicester Snodgrass with the Army to establish Coralie as next of kin.

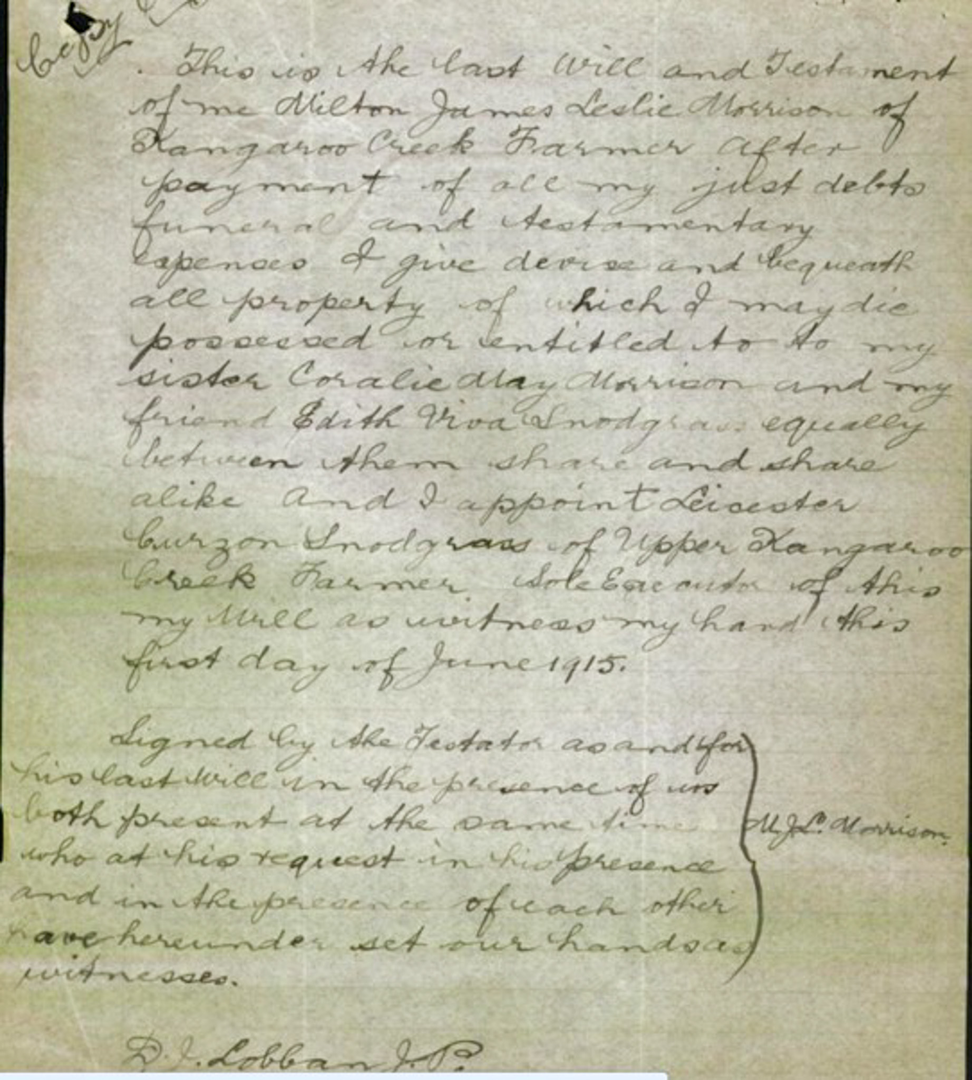

While Milton had stated his father as next of kin, it appears that he may have anticipated issues and on 1 June 1915, just before embarking, he had drawn up a will at Kangaroo Creek leaving his estate equally to his sister Coralie May Morrison and his friend Edith McLachlan, appointing local schoolteacher Leicester Curzon Snodgrass as executor.

Probate was published in the Daily Examiner in December 1917, confirming Snodgrass as executor of Milton’s will. In April 1920, Coralie wrote again, asserting her rightful claim as Milton’s nominated next-of-kin

“I am his only sister and was left next-of-kin, also his will. Pte. Morrison has never lived with his father since a small child, and his father knows nothing at all concerning him.”

Source - NAA. B2455, MORRISON, Milton James Leslie. First AIF Personnel Dossier p. 61

The Army then made a final attempt at contacting James to respond to the changing next of kin to Coralie.

As reflected in Milton’s files, the authorities finally accepted her claim as next of kin.

Although Milton and his siblings were not raised by their father, the ties were not completely severed.

A 1917 newspaper notice reported that:

“ Mr. J. Morrison, of Grey-street, Wickham, has received word that his eldest son, Private Milton James Leslie Morrison, who was reported as missing, was killed in action on July 19, 1916. Private Morrison, who left with the First Battalion, was employed near Grafton prior to enlisting.”

When Milton’s father James died in 1949, his funeral notices listed his surviving children — Clive, Coralie, and Frank — among the mourners, evidence that some measure of reconnection had taken place in later life. The Morrison family’s sacrifice did not also end with Milton. His paternal uncle, Charles Alexander Morrison, serving with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, was killed in France in October 1918. Two men of the same family, serving in different armies on opposite sides of the world, both lost in the battlefields of France. Private Milton James Leslie Morrison has no known grave.

His name is commemorated at:

- VC Corner Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles (No. MR 8)

- Australian War Memorial, Canberra (Panel 157)

- South Grafton Cenotaph, close to where he lived and worked before enlisting.

Family Reflections

Today, Milton’s story remains central to the work of remembering those who fell at Fromelles. His name stands among the “missing” — one of the young Australians whose bodies were never recovered — but his life is woven into the story of family, friends, mates, and community. Not much of Milton’s story was passed down in the family — for decades, it was shrouded in silence. His brothers rarely, if ever, spoke of their wartime losses or their difficult childhood as wards of the state.

Milton’s older brother Harold Raymond Brown went on to serve in the New South Wales Fire Brigade, eventually becoming an Inspector and representing volunteer firemen on the Board of Fire Commissioners. He died in 1953, aged 61, leaving behind his wife and daughter. Harold never spoke about his early life or about Milton.

His great-grandson Jeff Murphy recalled his mother saying:

“He never talked about his upbringing and never wanted to reveal it.”

Milton’s younger brother Cleveland Addison Morrison also remained silent. His son Colin, born when Cleveland was in his sixties, grew up never being told about his Uncle Milton, just small bits and pieces passed on from his older siblings.

Milton’s war medals remain in the Morrison family. Colin has proudly worn them on Anzac Day in Queensland, ensuring that his uncle’s sacrifice, once hidden, is now openly honoured.

Finding Milton

Milton’s remains were not recovered, he has no known grave. After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including 15 of the 190 unidentified soldiers from the 53rd Battalion. We welcome all branches of Milton’s family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification.

If you know anything of family contacts, especially those with roots in Narrabri, NSW and from the Morrison and Brown lines, please contact the Fromelles Association. We hope that one day Milton will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Milton’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Milton James Leslie Morrison (1894–1916) |

| Parents | James Addison Morrison (1867–1949, born Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, died Newcastle, NSW) and Vida Blanche Marian Brown (1864–1900, born West Maitland, NSW, died Narrabri, NSW) |

| Siblings | Harold Raymond Brown (1891–1953) | ||

| Cleveland Addison Morrison (1896–1971) | |||

| Coralie May Morrison (1898–1976), m. (1) George Charles McCarthy (1900–1964), m. (2) Leslie Robert Kent (1907–1981) | |||

| Wilfred Keith Morrison (1900–1904) |

| Half Siblings | Winifred Jean Morrison (1908–1940) | ||

| Patrick Charles Morrison (1911–2001) | |||

| Francis Addison Morrison (1914–1972) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | James Morrison (1832–1884) and Ann Addison (1845–1879) | ||

| Maternal | David Brown (1828–1886) and Elizabeth McGlynn (1837–1885) |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).