George David CHALLIS

Eyes brown, Hair brown, Complexion fresh

Sergeant George David CHALLLIS

This is a story of a soldier, a Carlton AFL player, killed in France as his Battalion made preparations for an engagement that we now know as the Battle of Fromelles, 19th – 20th July 1916. His story has been well documented and we acknowledge with thanks the following authors and publications whose work we have relied upon and reproduced in part with permission/acknowledgement to tell George’s story within the Fromelles context.

Ross McMullin, who included a biography of George Challis in his book ‘Farewell, Dear People: Biographies of Australia’s Lost Generation’ (2012).

Tony De Bolfo - The Great Fallen: George Challis - Carlton Media, Apr 20, 2015, 5:00pm

Andrew Rule - Lost and Found in Fromelles- Sydney Morning Herald, July 20, 2010

Ross McMullin - Bluebloods through the ages – The Age, August 24, 2012 — 6.29pm

Born 9th February 1891 in Cleveland Tasmania to Michael Charles (Charlie) and Margaret Challis (nee McGregor), George was a clerk in the audit department of the Victorian Railways who embarked from Melbourne on 27th October 1915 on board HMAT Ulysses with the 23rd Infantry Battalion.

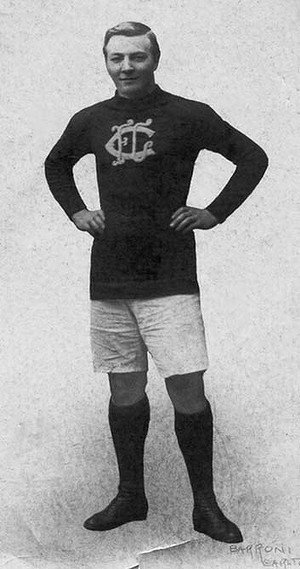

He was also an Australian Rules footballer who played for Carlton in the Victorian Football League. George was a well-known wingman who starred in Carlton’s 1915 premiership win wearing the number 12 jersey.

Ross McMullin, in his biography of George Challis (quoted in Tony De Bolfo’s article), describes George as follows:

“George was intelligent, widely admired and very popular. It wasn’t just that he was a brilliant player with dazzling skill and pace, and (unusual for the times) superb disposal — it was also the way he played the game. It was said that George always had a smile on his face. He was keen, he wanted to succeed and he wanted to win, but the crowd could tell George enjoyed what he was doing. He was known as ‘Cheerful Challis’ and ‘Genial George’.

Outside footy, George was very able scholastically. He won a scholarship that took him from the tiny Tasmanian hamlet of Cleveland, where he was born and raised, to Launceston where he went to secondary school. So impressed was the school’s headmaster with George’s academic prowess that he took George on as a teacher, and George was teaching at the time he made for the mainland across Bass Strait en route to Princes Park.

In Melbourne George took up work as an audit clerk with the Railways. As an example of the wide-ranging interests he developed, he also became an enthusiast of the Esperanto Society. This international language was probably not something your average VFL player was into, but it was reported in the papers of the day that he was an activist with the society in Melbourne.”

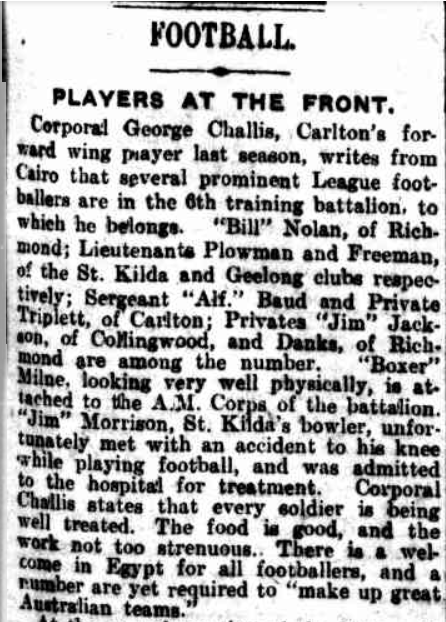

The news article below highlights a number of football stars of the era serving with George in Egypt. It has something of a recruiting tone - the food is good!

Sergeant Challis was serving with the 58th Battalion when he was killed on 15th July 1916 at Armentieres when a heavy caliber German shell dropped into his trench killing him instantly. He is buried in the Rue-Petillon Military Cemetery, Fleurbaix, France.

Ross McMullin in his 2012 Bluebloods through the ages article in The Age described events as follows:

“The 1915 grand final was his last VFL match. He was 24 and in his prime, but he left Australia aboard a troop ship soon afterwards. Sergeant Challis ended up in the 58th Battalion. After months of training in Egypt, he was conveyed to France with his unit in June 1916.

Challis went forward with his battalion to the front line near the village of Fromelles during the night of July 10-11. It was supposed to be a quiet sector, but the Australians found themselves thrown into round-the-clock preparations for an imminent assault towards the trenches opposite (which was carried out, disastrously, on July 19).

The Germans, for their part, were not inactive, either. They launched a raid on July 15, supported by a severe bombardment, and inflicted 160 casualties in the 58th Battalion. Challis was killed by a direct hit.

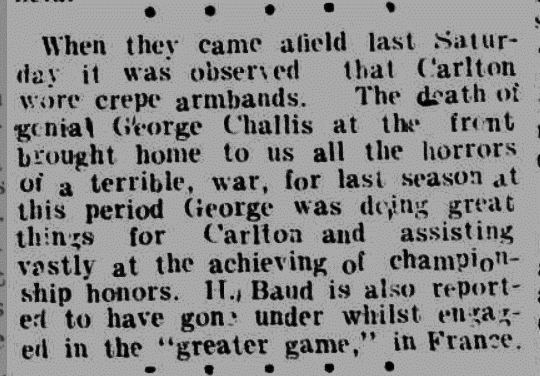

The news of his death reached Melbourne shortly before the 1916 football season ended. It was officially confirmed in a defence casualty list published on the day before the grand final. The timing seemed uncanny.

Hearing just before the grand final of the distressing death of a popular champion who had starred in the previous premiership decider symbolised for many the dreadful times they were enduring.

‘Expressions of regret were heard yesterday all over Melbourne when it became known that George Challis had fallen in France,’ the Adelaide Advertiser reported. In fact, he was widely mourned not just in Victoria.”

And later in the article, Ross recounted George’s last visit home to Tasmania and the reverence with which his memory was held:

“In July 1915, when Challis returned to Tasmania for the last time before he went to war, he caught up with relatives and friends at Cleveland and Launceston. He paid a visit to the little school at Cleveland, and all 20 or so of its young students were assembled to hear him speak. Football inevitably featured in his remarks: “When I come back I’ll teach you boys the finer points of the game," he said.

His death was deeply felt in Tasmania. Profound grief gripped the Cleveland community. Many homes in these districts retained a photo of Challis on a wall or mantelpiece for years.”

Bill Barry’s Diary

The next extracts are from the article, Lost and Found in Fromelles, by Andrew Rule (SMH 2010) and it provides a focus on Fromelles and the 2010 dedication ceremony. It highlights a diary that was instrumental in the story of the burial pits and is integral to the telling of George Challis’ story as well. Andrew begins:

“It's hard to say why a war fought so long ago still has such a potent effect after so many years. But in Fromelles these last few days you see proof of it and it brings a lump to the throat.

Here and at all the other battlefields in Flanders and the Somme, the Great War still echoes. Not just for relatives and descendants of soldiers who served but for others, too.

The 205 (sic) "lost diggers" re-interred in the new Pheasant Wood cemetery here were found — and 96 of them so far identified — because of Lambis Englezos, a Greek-born Australian with no connection to the 1914-1918 conflict except a feeling he cannot explain or ignore.

As the author Patrick Lindsay says of his friend: "You don't choose your obsession — it chooses you." There is no other way to justify the years of unpaid work that led to yesterday's ceremony.”

After some discussion of the ceremony and of the history at Fromelles, Andrew refers to the treasure that is Bill Barry’s diary, invaluable for its description of the German burial pit and for its reference to George Challis:

“A Northcote plumber called Bill Barry survived to write a first-hand account of what it was like to "die" on the field. Knocked unconscious by a shell blast that blew holes in his legs, he was tossed on a heap of bodies by a German burial party.

Barry woke to find himself surrounded by dead men ‘on the edge of a hole about forty feet long ... and into this hole the dead were being thrown without any fuss or respect.’

He would survive against all odds. Robbed and beaten at the front, he was sent to a German hospital where he was treated well and had his leg amputated. He was then released to England, where he would take tea at Windsor Castle before returning to Northcote with his extraordinary 65,000 word diary.

When Lambis Englezos read Barry's vivid account of the burial pit it confirmed his belief that at least 200 Australian dead were unaccounted for — and that all or most would be in the mass grave Barry had seen at what the Germans called Pheasant Wood, behind their lines in a field next to Fromelles village.

Bill Barry had seen other things, too. Four days before the suicidal attack of July 19, he wrote, "I passed a chap carrying something wrapped up in a blanket and when he was asked what he had he answered with a gloomy look on his face 'This is all that we could find of George Challis, the Carlton champion footballer.' He had been blown to pieces."

And, in the final reference to George in the article, Andrew says:

“There's a postscript to the story of George Challis. Here was one of Australia's best footballers, renowned for speed, reflexes and intelligence. But the army knocked him back the first time he tried to enlist — because one of his toes was bent.

Before 1916 only perfect physical specimens were good enough to be turned into carrion for King and country. After Fromelles, the requirements for trench fodder became less demanding.

‘By 1918,’ says the historian and author Les Carlyon, ‘they would have taken a budgerigar’.”

A Member of the Navy Blues 1915 Premiership Winning Team

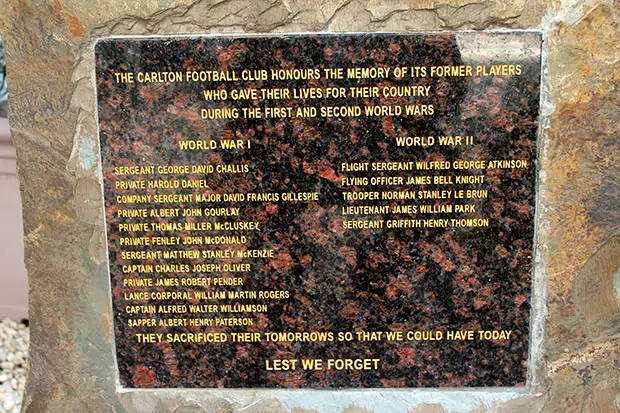

As a celebrated Carlton footballer, George Challis was a part of their winning 1915 Premiership and played 70 games for the club between 1912 and 1915. He was included in the club’s 2015 ANZAC tribute to the Carlton men who paid the ultimate sacrifice in World Wars 1 and 2.

On the club website, the article by Tony De Bolfo outlines George’s recruitment to Carlton after being talent spotted at the 1911 interstate carnival where George won a best player medal for his home state of Tasmania. He had a slow start in 1912 but:

“he gradually got into his stride, and became a brilliant performer in a succession of games for his new club………”

“Injury unfortunately cost George a place in Carlton’s 1914 premiership team, but he overcame that setback and, wearing the No.12, was considered amongst his team’s best players afield in the 1915 Grand Final victory.

At the end of the 1914 season, after the outbreak of hostilities in Europe, George tried to enlist with his Carlton teammate and close friend Stan McKenzie. But there was an unexpected stumbling block in that while Stan got a tick and went off to war, George was adjudged to be medically unfit because he had one toe slightly overlapping another.

But George kept trying and in the end was accepted. That happened in July 1915 after the Gallipoli landing, when word filtered back of the substantial casualties and the authorities stopped fussing about technicalities.”

George was made a sergeant soon after enlisting. In recognition of his leadership qualities, he was told that officer training was open to him to become a lieutenant. George said no, I’ve enlisted to fill gaps and the sooner we get over there the better, so he declined that offer and remained a sergeant.

Tony then goes on to describe George’s death on 15 July 1916:

“His death occurred in the lead-up to the notorious battle of Fromelles, the worst 24 hours in Australian history, when there were 5533 Australian casualties in one night. That battle actually started on the 19th, but four days earlier the Germans launched a major raid supported by a severe bombardment, which caused 160 casualties in the 58th Battalion . . . amongst them George, who was blown to bits by a direct hit.

George was very much a battalion favourite — so much so that his many admirers decided to gather what was left of him to get him properly buried . . . and they collected his remains in a blanket. He was buried nearby, in the cemetery at Rue Petillon.”

Back in Australia, George’s death was confirmed just days before Carlton took the field for the 1916 Grand Final. The Carlton team wore black armbands to acknowledge their fallen comrade.

And finally, Tony reflects on how George was remembered, never to be forgotten:

“George’s parents Charlie and Margaret were invited to choose an inscription for their boy’s grave. In response, they provided the following epitaph: ’Tho’ death divides, fond memory clings’.

Charlie and Margaret never visited George’s final resting place, but their son’s epitaph remained forever in their thoughts after the government supplied them with graveside photographs.

A memorial stone for George was also erected in Cleveland cemetery, and at the little nearby church there’s a memorial to him. If you peer through the window you can see his name there, at the top of the Honour Roll for Cleveland’s war dead.

But remembrance of George Challis extended beyond headstones and honour boards. He was fondly recalled extraordinarily often by nostalgic Tasmanians and frustrated Carltonians who lamented his absence as they ruefully looked back to the good old days.

Joe Lyons, who was to become Prime Minister of Australia, knew the Challis family well in his early days as a teacher, and he used to watch George play for Launceston whenever he could.

Years later, on an emotional pilgrimage to Fromelles as Prime Minister, Joe paid his respects at George’s grave.”

Tho death divides, fond memory clings

As a much-loved son and brother, a valiant soldier and a celebrated sportsman, George is commemorated to this day. In addition to his headstone at Rue-Petillon Military Cemetery and the Carlton Football memorial, his name is inscribed on the following:

- Launceston Church Grammar School WW1 Honour Board, Tasmania

- The Campbell Town Roll of Honour, Town Hall, Campbell Town, Tasmania

- St Luke’s Anglican Church War Shrine, Campbell Town, Tasmania

- Campbell Town War Memorial (Cenotaph), Campbell Town Oval, Tasmania

- Christ Church Anglican Honour Board, Conara, Tasmania

- Chalmers Presbyterian Church Roll of Honour (now Pilgrim Uniting Church, Launceston). Tasmania

- Tamar Rowing Club, Launceston, Tasmania

- Headstone at Cleveland Union Chapel Cemetery, Cleveland Tasmania – this includes his details and the inscription: He gave his life, his best, his all. (It also commemorates his siblings, Emma and Harold)

- Panel 165 in the Commemorative Area at the Australian War Memorial, Canberra, ACT

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).