William James CONNELL

Eyes brown, Hair brown, Complexion fresh

William James Connell

Can you help find William?

William was killed in Action at Fromelles, but his body has never been identified.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification.

If you know anything of family contacts for William in Australia or Scotland, please contact the Fromelles Association.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

Early Life

James William Connell was born in 1881 in Hotham (now called North Melbourne), in Victoria, the son of James William Connell and Margaret Henderson. He was known throughout his life as William James or simply William. His father was from Midlothian Scotland and his mother was born in Victoria. In 1888, they were all living in North Carlton at 311 Canning street, the home of William’s maternal grandmother.

Children of James and Margaret:

- Christina Brier Connell (born 1877), married William Henry Smith

- Jeanetta Harriet Connell (1879-1897)

- William James Connell (born 1881-1916)

- Henry Connell (1884 -1888)

- Margaret Rose Australia Connell (born 1888)

1888 was a year of great sadness and change for the Connell family. William was just seven and his mother, having given birth to Maggie, died of renal failure and Henry, aged 4, died later that year. This left William’s father to raise all the young children. How did they manage? We know that they went to NSW at some stage, as Janet died in 1897 at Wickham, NSW, aged 18.

This may have been an employment move, as Newcastle and the mining areas were booming. William went on to work as a labourer. William’s father died in 1912 in Rockdale, Sydney. William and his sister Maggie remained in NSW and they lived together at Brunda, Ocean Street, Woollahra, Sydney. Maggie was listed as his next of kin when he enlisted – a reflection of their close bond and shared home before he left for war. Maggie never married. She died at Leura in 1972, aged 87.

Off to War

William enlisted on 24 June 1915, at Liverpool, New South Wales. At 33 years old, he was older than many of his fellow recruits, but like so many, he was likely driven by duty and adventure far from home. He was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 9th Reinforcements, and embarked from Sydney on 30 September 1915 aboard HMATArgyllshire. William arrived at Port Said in Egypt in the first week of January 1916 and was moved to the training camp at Tel-el-Kebir, which was about 110 km northeast of Cairo.

The 40,000 men in the camp were comprised of Gallipoli veterans and the thousands of reinforcements arriving regularly from Australia. With the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five, major reorganisations were underway. The 53rd Battalion was formed on 16 February 1916 and was made up of Gallipoli veterans from the 1st Battalion and the new recruits from Australia and William was reassigned here. The Gallipoli soldiers in the 53rd were not slow in pointing out to whoever would listen that they were the “Dinkums” and the new recruits were the “War Babies”.

Source: AWM4 23/70/1, 53rd Battalion War Diaries, Feb-July 1916, page 3

Training for all continued. In March they were sent to Ferry Post, on foot, a trip of about 60 km that took three days. It was a significant challenge, walking over the soft sand in the 38°C heat with each man carrying their own possessions and 120 rounds of ammunition. Many of the men suffered heat stroke.

Once there, they remained at Ferry Post guarding the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army until 16 June when they began the move to the Western Front. 32 officers and 958 soldiers of the 53rd left Alexandria on 19 June on the troopship HMT Royal George, bound for Marseilles, France to become part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front. They arrived in Marseilles on 28 June and immediately entrained for a 62-hour journey north to Hazebrouck before finally marching into the camp at nearby Thiennes in northern France. During their trip it was noted that their “reputation had evidently preceded them”, as they were well received by the French at the towns all along the route.

Source: AWM4 23/70/2 53rd Battalion War Diaries February - June 1916, p. 4

This area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long.

On 10 July, the 53rd entered trenches for the first time. Though nominally in a "quiet sector", the front near Fleurbaix was anything but calm. Rain flooded the communication trenches, artillery fire harassed supply lines, and the soldiers dug in amid the mud and barbed wire of No-Man’s-Land.

From 8 to 16 July, the 53rd rotated between billets and the line. The men knew something was coming. They rehearsed attacks in replica trench systems, inspected bayonets, and watched as huge guns rolled into place behind the lines. Then on 16 July, they moved up for an attack—only to have it postponed due to weather.

The delay proved torturous. Private James Charles "Jim" Granger, 4784, 53rd Battalion, a young Dorrigo soldier, described the tension leading up to the battle:

““We were held in suspense for three days… like a criminal waiting to hear the verdict.

We had no dugouts where we were in the supports and shrapnel was bursting all round.””

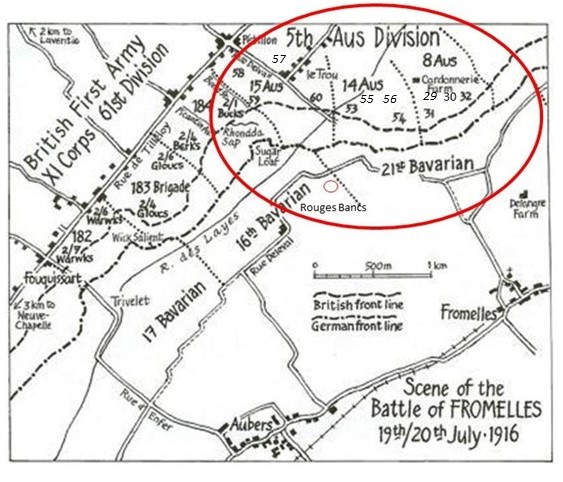

The Battle of Fromelles

On 8 July they began a 30 km march to Fleurbaix and were settled into billets there on 16 July. Early the next morning, the 53rd were moved straight into the front lines for the main attack, but it was cancelled due to bad weather. They remained in the trenches in relief of the 54th.

On the 19th, heavy bombardment was underway from both armies by 11.00 AM. At 4.00 PM the 54th Battalion rejoined on their left. All were now in position for battle. Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties.

The main objective for the 53rd was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the 53rd and the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfiladed fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 60th and 54th Battalions on their flanks.

The Australians went on the offensive at 5.43 PM. They moved forward in four waves – half of A & B Companies in each of the first two waves and half of C & D in the third and fourth. They did not immediately charge the German lines, they went out into No-Man’s-Land and lay down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift .

Private Arthur Norton Crewes, 4755, 53rd Battalion wrote at the time:

“At 5.43 pm the signal for the charge sounded, and over the top we went into the face of death, shells bursting, machine guns rattling and rifles crackling.”

At 6.00 PM the German lines were rushed. The 53rd were under heavy artillery, machine gun and rifle fire, but were able to advance rapidly.

Corporal J.T. James of C Company (3550) reported:

“At Fleurbaix on the 19th July we were attacking at 6 p.m. We took three lines of German trenches”

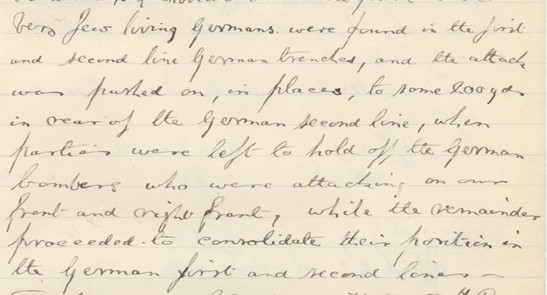

As below, the 14th Brigade War Diary notes that the artillery had been successful and “very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches”, but within the first 20 minutes the 53rd lost ALL the company commanders, ALL their seconds in command and six junior officers.

Source: AWM C E W Bean, The AIF in France, Vol 3, Chapter XII, pg 369

According to witness statements, William was killed in this fateful initial rush:

“Fleurbaix. Killed by bullet out in No Man's Land, 19th July. Saw him dead, was with him at the time, same from Leichhardt, Sydney; he was my section commander.”

And in a later statement:

“Informant was told by Pte. Adams of A Coy, that Connell was killed in the attack on this date.”

Further confirmation came from another comrade:

“Informant was told by Pte. Adams of A Coy, that Connell was killed in the attack on this date.”

Some of the advanced trenches were just water filled ditches, which needed to be fortified by the 53rd to be able to hold their advanced position against future attacks. They were able to link up with the 54th on their left and, with the 31st and 32nd, occupy a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm, but the 60th on their right had been unable to advance due to the devastation from the machine gun emplacement at the Sugar Loaf.

They held their lines through the night against “violent” attacks from the Germans from the front, but their exposed right flank had allowed the Germans access to the first line trench BEHIND the 53rd, requiring the Australians to later have to fight their way back to their own lines.

By 9.00 AM on the 20th, the 53rd received orders to retreat from positions won and by 9.30 AM they had “retired with very heavy loss”.

Source: AWM4 23/70/2 53rd Battalion War Diaries July 1916 page 7

Of the 990 men who had left Alexandria just weeks before, the initial count at roll call was 36 killed, 353 wounded and 236 missing:

“Many heroic actions were performed.”

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The final impact of the battle on the 53rd was 245 soldiers were killed or died from their wounds and, of this, 190 were not able to be identified.

After the Battle

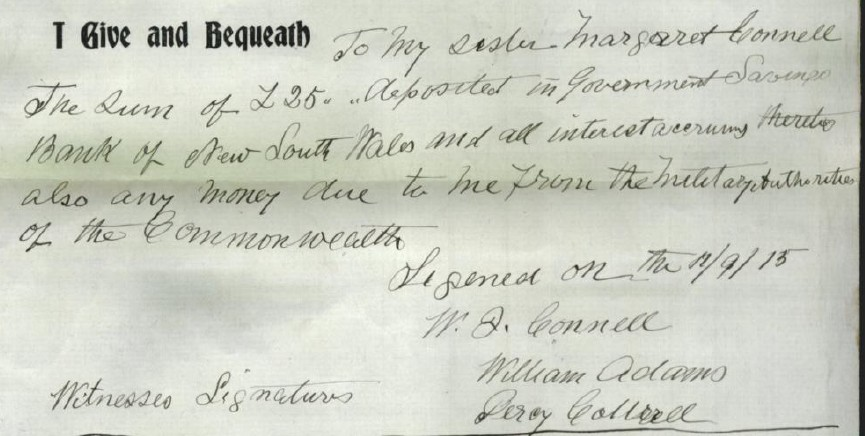

When the guns finally fell silent after the failed attack at Fromelles, the full horror of the battle was revealed. The 53rd Battalion alone lost nearly half its men killed, wounded, or missing. William was initially listed as missing in action and for weeks his family clung to hope. His sister Maggie, waiting at their home in Woollahra, Sydney, would have checked every casualty list for his name. As Red Cross enquiries gathered witness reports, confirmation eventually reached her that William had been killed on 19 July 1916. With their close relationship, Maggie was the beneficiary in William’s will.

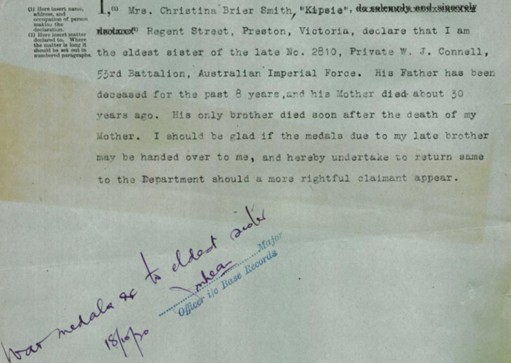

Despite multiple eye-witness statements describing his death in No Man’s Land, not far from the Australian lines, William’s body was never recovered. The battlefield remained under German control for the remainder of the war, and many who fell that night were buried where they lay or interred later in mass graves. In the years after the war, William’s eldest sister, Christina, who was living in Melbourne, applied to receive his war medals on behalf of their family. In her declaration, she explained that their parents had long since passed away and that William’s sister Janet and only brother had died in childhood, leaving Christina and his sister Maggie to carry forward his memory.

Today, William is commemorated on Panel 7 at the VC Corner Cemetery Memorial in Fromelles, France, alongside over 1,200 Australian soldiers who died in the battle with no known grave. His name is also recorded on the Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour in Canberra. For his family, there was no grave to visit and no final resting place to mourn. Like so many of the men lost that night, William remains one of the missing.

Finding William

After the battle, the Germans did recover 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including 15 of the 190 unidentified soldiers from the 53rd Battalion.

Some members of William’s family have come forward to provide DNA, but we welcome all branches of the family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification. We hope that one day William will be named and honoured with a known grave. If you know anything of William’s family contacts in Australia or Scotland , please contact the Fromelles Association.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and William’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | William James Connell (1881–1916) |

| Parents | James William Connell (1854–1912) and Margaret Henderson (1853–1888) |

| Siblings | Christina Brier Connell (1877–1961), married William Henry Smith - two daughters on DNA line needed. | ||

| Jeanetta Harriet Connell (1879–1897) | |||

| Henry Connell (1883–1888) | |||

| Margaret Rose Australia Connell (1888–1972) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Peter Connell (1832–1896) and Janet Morrison (1827–1859) | ||

| Maternal | Hugh Henderson (1822–1885) and Christina Brier Ensor (1832–1903) |

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).