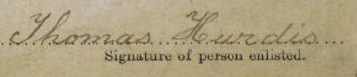

Thomas HURDIS

Eyes brown, Hair auburn, Complexion fresh

John and Thomas Hurdis - ‘Troubled’ Youths, but Brave Soldiers

Thomas and John Hurdis were the sons of John and Harriet (nee Claridge) Hurdis. They also had two sisters, Mary and Alice. Thomas was born on 1 June 1890 in Newtown, New South Wales and John on 2 March 1896 in Wedderburn, New South Wales.

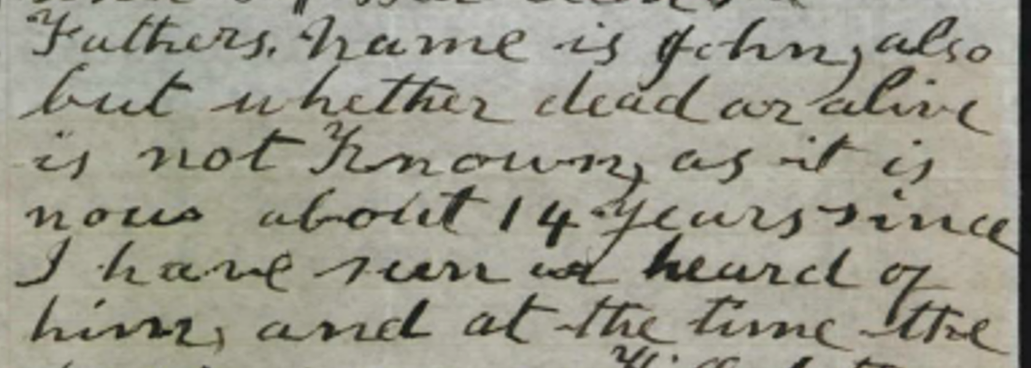

The family was not well off. The boys’ father was a builder, but he seems to have been largely absent, possibly in South Africa for some time. In a letter from Harriet to the AIF in 1920, she had not known of her husband’s whereabouts for many years. With a limited income and effectively a single mother, Harriet and her family often moved throughout the western suburbs of Sydney. The Warialda Street address given on the boys’ AIF records for their mother as next of kin is possibly the address of Harriet’s brother, John Claridge.

Thomas attended school in Leichhardt and John in Alexandria. Both boys had run-ins with the law for committing minor thefts. At his first trial, Thomas, just 11 at the time, admitted to the theft but said:

I was hungry and wanted to buy some bread and jam.

At 15, John also admitted his wrongdoing, but he stated that he ran away from a family he was boarding with and stole some fruit from a church harvest festival. All in all, it was a difficult upbringing for both of them.

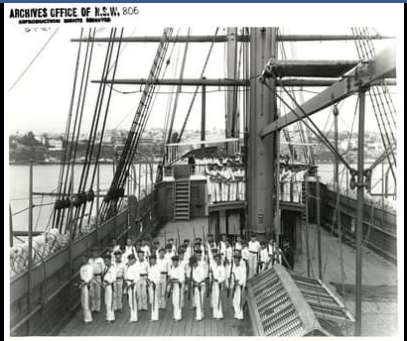

Thomas and John were both, at various times, sentenced to the Carpentarian and Brush Farm reform schools, as well as time aboard the Sobraon, a reformatory school based on a ship where wayward boys were taught seafaring and trade skills. Thomas had a tattoo of an anchor on his left arm, possibly because of this experience.

For life on the Sobraon, think sailor suits, nautical skills, hard work, and discipline. But also think picnics, gardening, and playing cricket on Cockatoo Island. There was a library, a games room, craft lessons and excursions.

When they enlisted in the AIF, Thomas, 26 years old, was working as a labourer in Yetman, far north NSW and John was a farm worker in Numbaa, just near Nowra south of Sydney.

John was apprenticed to Numbaa farmer D. O’Keefe and was good mates with young Hughie Dwyer, a ward of the state who had been fostered by another Numbaa dairy farmer, Jack Murphy. Hughie was destined to become the Australian lightweight, welterweight and middleweight champion and in his early boxing days, he became captivated by :

“advertisements published by Reg “Snowy” Baker and with another neighbourhood lad, Jack Hurdis, invested in a postal course and received an instruction book on boxing”

Both Hurdis and Dwyer took part in a local championship bout in 1914 with Hughie qualifying to take part in the championship fight. We don’t know Jack Hurdis’ level of boxing expertise but he was evidently a keen participant.

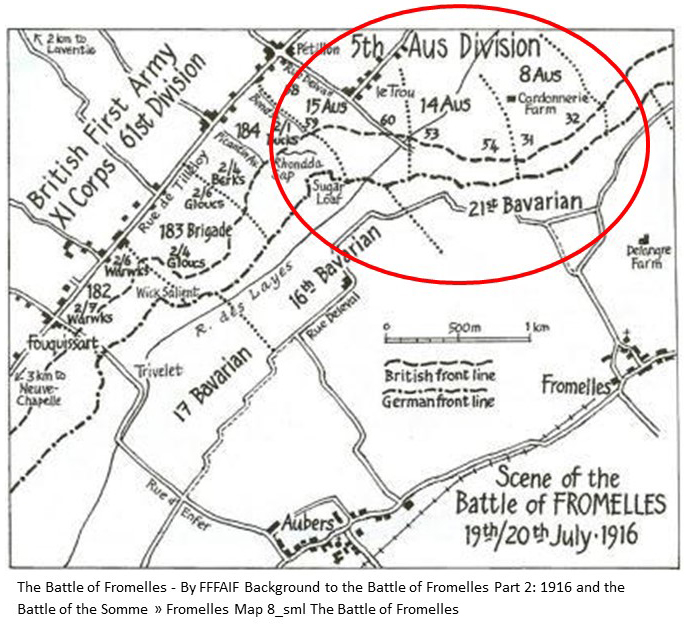

John’s War – Fromelles

At just 19 years old, John felt the call to duty and enlisted on 23 June 1915. His boxing mate, Hughie Dwyer, also tried to enlist but was rejected due to his deficient chest measurement.

John was assigned to the 9th reinforcements of the 2nd Battalion and began his military training at the Liverpool New South Wales Camp and on 30 September 1915 he was on board HMAT A8 Argyllshire for the one-month voyage to Suez, Egypt.

The 2nd Battalion was still fighting in Gallipoli when John arrived in Egypt, so John’s reinforcement groups would have continued their general training. The 2nd Battalion arrived in Egypt at the Tel el Kebir camp on 31 December and John was taken on strengths with the battalion on 6 January 1916.

With the heavy losses at Gallipoli and the many new recruits coming in from Australia, a complete reorganization of the troops for duty on the Western Front was underway. As a result, John was reassigned to the newly formed 54th Battalion on 14 February and training of the old and new hands continued.

John’s troubles from his youth were now well behind him as he was promoted to Lance Corporal on 1 March 1916 – the day before his 20th birthday.

The call to the Western Front came, and on 20 June the 982 soldiers of the 54th Battalion left Egypt, sailing to Marseilles via Malta on the HMT Caledonia to join with the British Expeditionary Force. After a 10-day trip, the troops disembarked in France and were put on trains for the three-day trip to Thiennes, 30 kilometres west of Fleurbaix.

By 2 July, the Battalion was billeted in barns, stables and private houses. Training now included use of gas masks and exposure to the effects of the artillery shelling. It was hoped that these tests would "inspire the men with great confidence". Source: AWM Diaries

On 10 July, they were moved to Sailly sur la Lys and on the 11th they were into the trenches in Fleurbaix for the first time. The health and spirit of the troops was reported as good.

After a few days getting exposed to the trenches, they moved back to billets in Bac-St-Maur.

Roy Harrison, a Captain in the 54th who had experienced the Gallipoli battles, wrote to his fiancée of the situation:

“The men don’t know yet what is before them, but some suspect that there is something in the wind. It is a most pitiful thing to see them all, going about, happy and ignorant of the fact, that a matter of hours will see many of them dead; but as the French say ‘C’est la guerre’.”

An attack was planned on the 17th so they went back into the trenches, but it was delayed due to the weather. The weather soon improved and by 2.00pm on 19 July they were again in readiness to face the German troops.

Their attack began at 5.50pm. There was heavy artillery, machine gun and rifle fire, but the 54th were able to advance rapidly occupying the German trenches by 6.00pm. Some of the advance trenches were just water filled ditches.

Fighting and shelling continued throughout the night. With heavy losses and the German counterattacks, the Australians were eventually forced to retreat. By 7.30am on the 20th, the 54th were pulled all the way back to Bac-St-Maur, 5 kilometres from the front.

In this very short period of time, about 250 of the 982 soldiers of the 54th that left Egypt were recorded as killed or missing.

John’s Fate

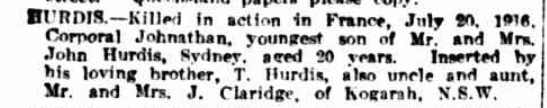

John was declared as killed in action, but there are no Red Cross reports about his death and there are no records of his burial.

His family was notified and his death was reported in the local papers by 18 August 1916. The official declaration came later in a 27 September 1916 report.

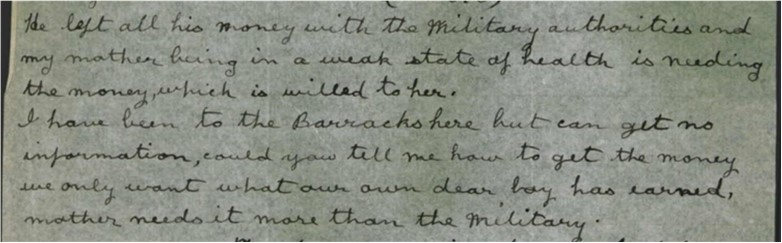

John’s sister, Mary, wrote to the AIF in December 1916 seeking the return of his belongings, which included money he had earned and saved. She wrote, “my mother was in a weak state of health” and “we only want what our own dear boy has earned, mother needs it more than the military.”

John’s belongings, including his identity disc, were returned, but not until July 1917. While Harriet was his next of kin on his enlistment papers, with Harriet’s inability to provide any details about his father it took until 1920 to sort out his pay.

Harriet wrote several times more, seeking information on where John was buried. There was a major post-war effort by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to find soldiers buried at the battle sites, but John’s burial place was not found or identified.

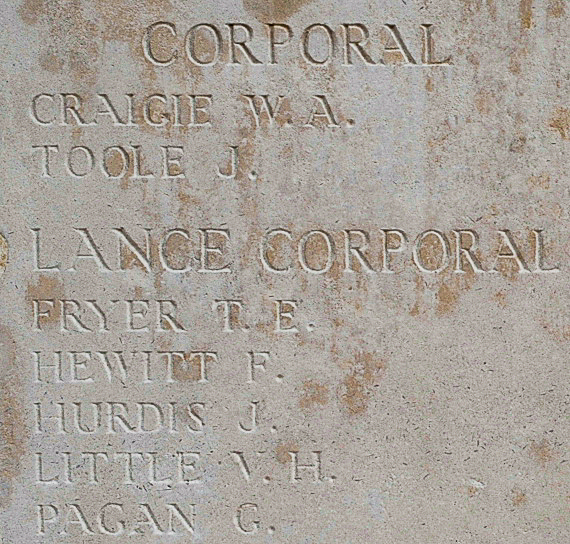

John was awarded the 1914-15 Star, Victory Medal, British War Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll. He is commemorated at Panel 10 at VC Corner, Australian Cemetery and Memorial, Fromelles, Panel 159 at the Australian War Memorial, Canberra and the Soldiers’ Memorial in Nowra, New South Wales, in the district where he was working before he enlisted.

Thomas’s War

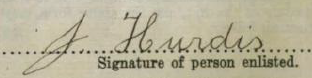

John’s death must have had an impact on Thomas. He placed his touching family notice (pictured previously) in mid-August 1916 and then enlisted on 12 September 1916.

He was assigned to the 7th Reinforcements of the 59th Battalion. After a short period of training, he left for Europe on 3 November on board HMAT A19 Afric, arriving at Plymouth, England on 9 January 1917. His military training continued with the 15th Training Battalion at the Hurdcott camp and on 28 March 1917 was sent to France to join the 59th Battalion at Reincourt les Bapaume, north-east of Amiens.

The 59th were not involved as a main attacking battalion during the April-mid September period, but Thomas did get a taste of action just two days after he arrived, moving into the front-line trenches at Doignies to defend the gains made there. He was also in the front lines at the second Battle of Bullecourt in early May, ready to move forward if required. Afterwards, they were moved between several locations near the Belgium border, but their time was spent training, not fighting.

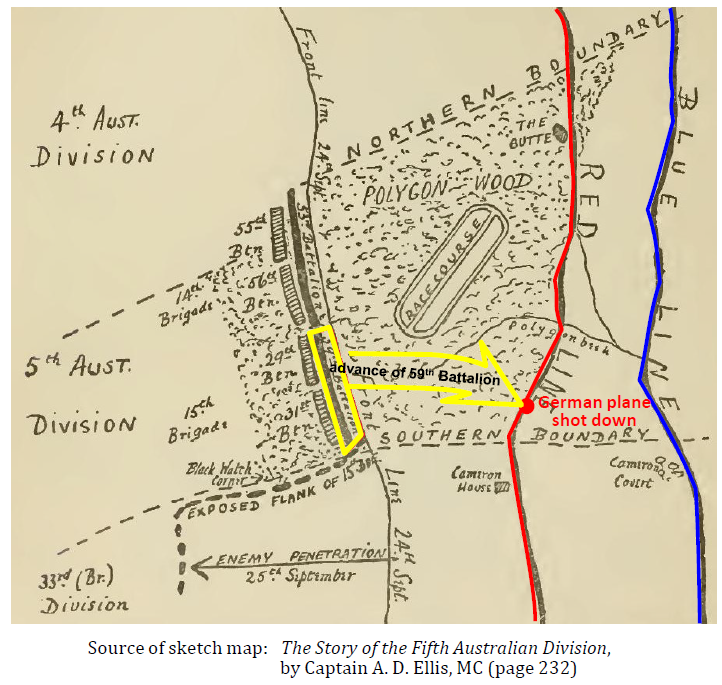

On 17 September they were finally called into action and began to move the 50 kilometres from their camp in Sercus, France to Polygon Wood, Belgium. On the 24th, they arrived at Zillebeke Lake, 6 kilometres from the battle lines at Polygon Wood. During their week-long transit they spent their time practising their role in the attack plan, which involved multiple Australian and British battalions.

Arriving on September 24th, they were in position to fight at 2.17am on the 26th. B & C Companies were to lead the charge with Thomas’ A Company to do the “mopping up” for their Battalion.

C.W. Bean described the start of the battle :

The barrage, which descended at 5:50 (AM) on September 26th, just as the Polygon plateau became visible, was the most perfect that ever protected Australian troops. The ground was dry, and the shell-bursts raised a wall of dust and smoke which appeared almost to be solid. So dense was the cloud that individual bursts, except the white puffs of shrapnel above its near edge, could not be distinguished. Roaring, deafening, it rolled ahead of the troops “like a Gippsland bushfire.”

By 5.53am, the first objective, a strong point in the German lines (the red line in the map above), had been secured.

However, the 33rd British Division troops on their right had come under fierce resistance from the Germans and not been able to advance, leaving 200 yards of the 59th’s right flank exposed. As a result, some of the 59th troops had to fall back and, as described in the War Diaries, “it was here the major portion of casualties were suffered.”

The battle continued throughout the day. There were dozens of German concrete pillboxes protecting the machine gunners. At about 4.45pm, a German aeroplane, firing from a height of about 50 feet at men of Thomas’ A Company, was shot down almost on top of the Australians in their trench.

The 59th were able to link up with the Australian 14th Brigade on their left and later with the British on their right and the second objective was achieved. The battalion was relieved by the 29th Battalion at 2.00am on the 28th.

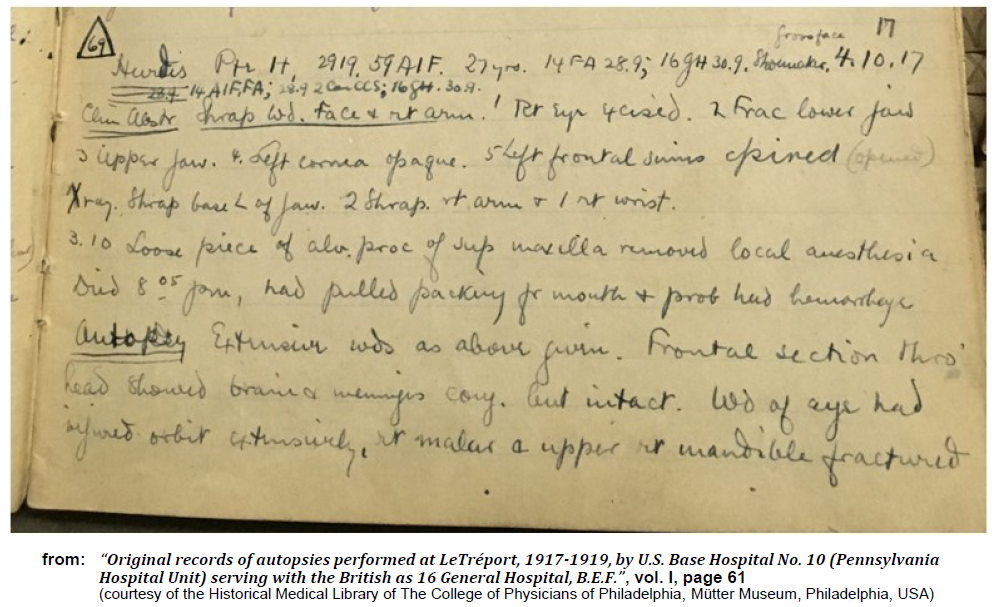

Thomas was one of 200+ casualties from the 716 soldiers of the 59th. He had multiple shrapnel wounds but was not killed outright. He was hit by at least five pieces of shrapnel from an artillery shell: one entering the lower left jaw and exiting the upper right jaw (causing the most damage), a second embedded in the skull in the forehead above the left eye, two more causing wounds in the right arm and one in the right wrist.

In his terrible state, he was taken to the 14th Australian Field Ambulance Casualty Station at Menin Rd, then to the 2nd Canadian Casualty Clearing Station at Remy Siding. Finally, he was sent by ambulance train nearly 200 kilometres to the 16th USA General Hospital, Le Tréport, France on September 30th 1917.

A Philadelphia ophthalmologist and surgeon, W.T. Shoemaker, treated Thomas. He said that:

“This soldier survived his initial injuries and treatments. But five days after his injuries, blind and disoriented, he pulled out the bandage materials in his mouth that packed the wounds. He bled to death.”

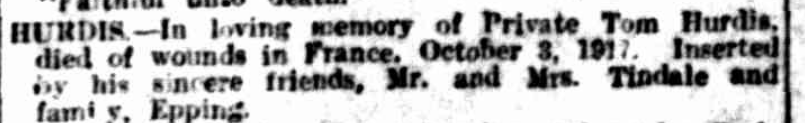

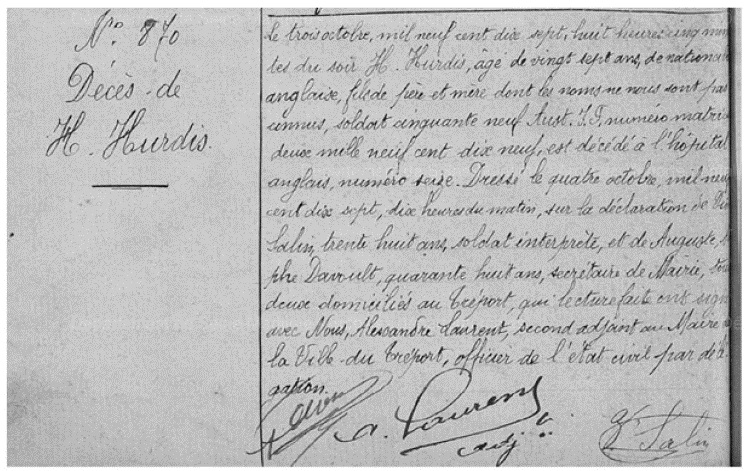

Thomas died at 8.05pm on 3 October 1917, aged 27 years and 4 months. He was buried by Padre Rev. Edward Jefferys on that same day at the Mont Huon Military Cemetery (Plot IV, Row O, Grave No. IA), Le Tréport, France.

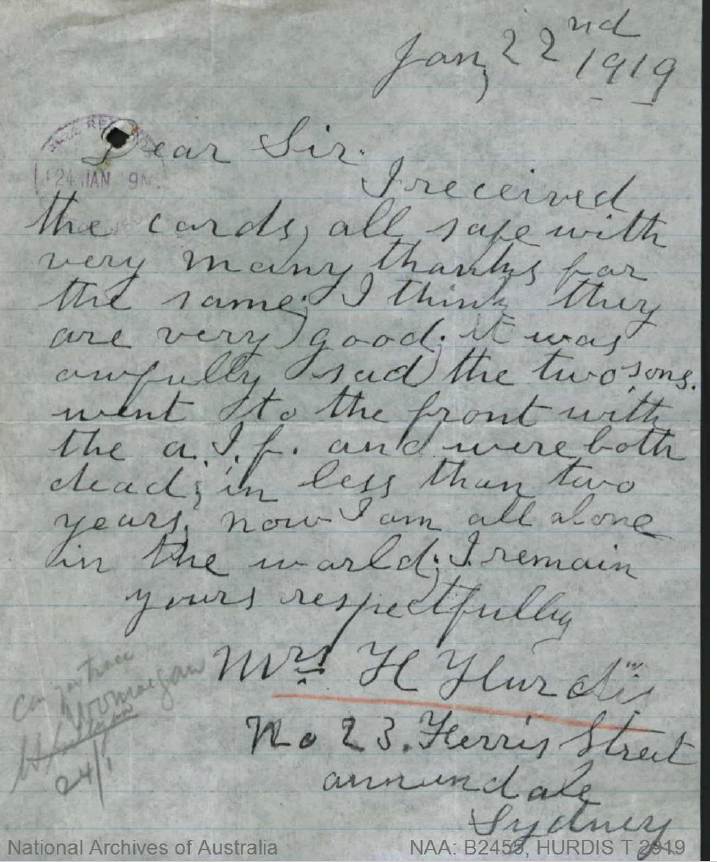

“I am all alone in the world”

The family was advised shortly after Thomas had died and news spread to the community as well. On 16 October 1917, a Miss Sutton from Yetman, where Thomas had worked before enlisting, wrote and questioned if he had been taken prisoner or not.

Harriet also had a number of communications with the army about receiving her son’s personal effects and photos of his grave, which they did provide. Her most telling one demonstrating the depth of her loss was written in January 1919:

“It was awfully sad the two sons went to the front with the A.I.F. and were both

dead in less than two years. Now I am all alone in the world.”

Thomas was awarded the British War Medal, Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque, and a Memorial Scroll. He is also commemorated at the Australian War Memorial, Canberra, Panel 167, the Warialda and District First World War Honor Roll, and the Yetman First World War Rolls of Honour.

Epilogue

Thomas was in the news again more than 100 years after his death. With the unusual nature of his wounds, his skull had not been buried with his body, but it had been kept for pathological studies:

“a product of a desire to learn from the medical developments and experiences of the (sic) World War One" as the US doctors had very little experience in treating the types of wounds suffered on the Western Front.

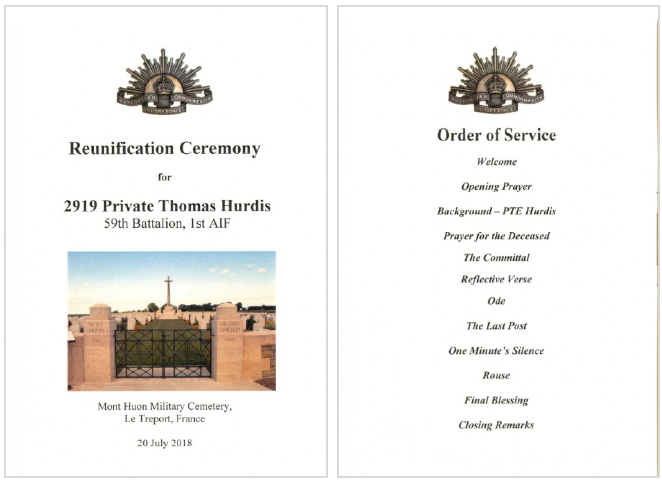

When it was discovered that his skull was in the Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, actions were taken by Australian authorities to return the skull. It was respectfully interred in his grave in a ceremony on 20 July 1918.

The ceremony was conducted by Colonel S. Clingan (Defence Attaché Ceremonial, Australian Embassy, Paris) and Rev. Patrick Irwin (formerly of St James’ Church, Sydney). Mr John Hurdis attended to represent the Hurdis family and others present included:

- Mr Brendan Berne, the Australian Ambassador to France

- Mrs. Jennifer Stephenson, the First Secretary, Western Front Commemorations, Department of Veteran’s Affairs, Australian Embassy, Paris

- M. Jacques Laurent, the Mayor of Le Tréport

- Representatives of the Armée de Terre (French Army)

- Representatives of the Association des Anciens Combattants (Association of Former Servicemen, French ex-servicemen, equivalent of the RSL)

- Representatives of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission; and

- Other local French residents and French officials.

Merelyn McKenzie (nee Hurdis), a distant cousin who was unable to attend the farewell ceremony said, “We hope it will mean that his soul will be at peace now.”

DNA donors are still being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Jonathan John HURDIS 1896-1916 |

| Parents | John HURDIS | ||

| and Harriet CLARIDGE 1863-1925 New South Wales |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Unknown | ||

| Maternal | John W. CLARIDGE, b 1829 England d 1902 NSW and Charlotte I. COOPER, b 1829 England d 1900 NSW. |

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).