William BOYCE

Eyes blue, Hair light brown, Complexion sallow

"No, Jim, I’m not dead yet" – Bill Boyce

In compiling Bill’s story, we acknowledge with thanks material from the Department of Veteran Affairs, namely an interview with Bill Boyce by Jill Morrison in August 1994 [AWM C386815] and a 1992 interview by Lambis Englezos with Bill and the article written by Lambis in the VetAffairs journal, July 1993 [NLA – Trove, Vetaffairs]. Links to these invaluable resources are included at the end of this story.

Background

William Boyce was born on 18 May 1893 in Briagolong, Victoria, 240 kilometres east from Melbourne in the Gippsland area. His parents were Mary (nee Williams) 1859-1940 and Tanjore Boyce 1846-1902 and Bill was the seventh of their ten children, seven girls and three boys.

In about 1902, the family moved from Gippsland to the Warrnambool area, near where Bill’s father was originally from. Sadly, his father, a miner and beekeeper, died shortly after the move, leaving his mother widowed with ten children.

Bill’s first work was looking after racehorses. While he loved horses, he realized that horses were going to be replaced by motorcars and he became a mechanic/driver.

Joining Up and Off to Egypt

With the start of the War, Bill said that a key factor in his decision to enlist was the German’s sinking of the Lusitania in early 1915. “If there was a nation on earth that was as bad as that they should be stopped,” he said.

At 22 years old he joined up on 5 July 1915 in Melbourne and was assigned to the 21st Battalion, 7th Reinforcements. Army training began in the camp in Broadmeadows, Victoria. Bill said he “already was a good shot before joining, but it took a while to be accustomed to drill work.”

His unit embarked from Melbourne aboard HMAT A18 Wiltshire on 18 November 1915, heading to Egypt. He recalled being “excited, to a certain extent” to be leaving Australia.

With the thousands of recruits arriving in Egypt, there was a good deal of reorganization of the troops. Bill was re-assigned to the 60th Battalion on 26 February 1916, but less than three weeks later on 15 March, he was reassigned to the 58th.

The Australian troops spent their time training and guarding the Suez Canal at Tel el Kebir, Ferry Post, Hogsback and Moascar. By early June, the 58th Battalion was at a total strength of just more than 1000 men.

They then went to Alexandria on 17 June on board the Transylvania, arriving in Marseilles on the 23rd. From there they had a three-day train ride to Steenbecque, 35 kilometres from Fleurbaix.

Bill’s comment on his reactions to being in France? “[Egypt] was possibly the world’s worst way to prepare for France.”

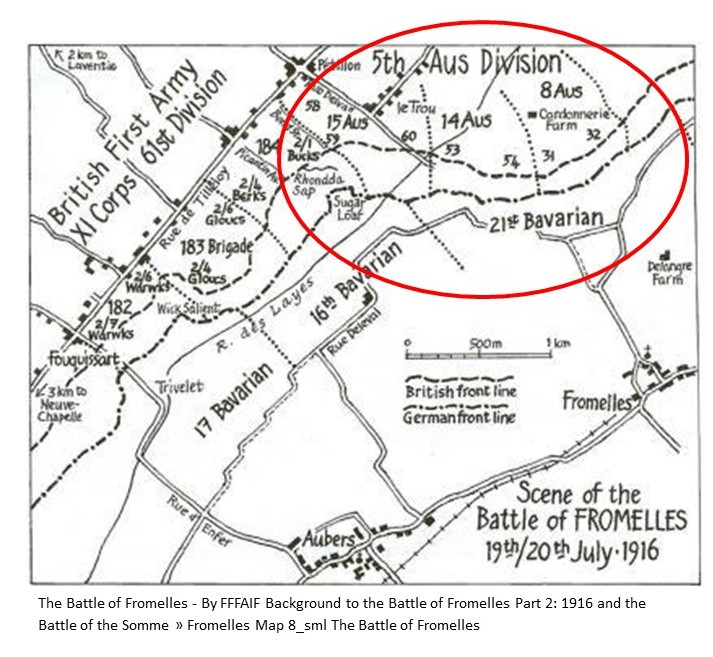

Fleurbaix – Straight into Battle

After marching to Fleurbaix and some further training, including the use of gas masks, they were into the trenches for the first time on 11 July.

The 58th Battalion’s role in the battle was in support of the 59th and 60th, carrying ammunition, digging the communication trenches for area gained in No Man’s land and relief as needed for the attack. Bill was to be one of those digging the trenches. “What have I let myself in for?”

They were in position at 9.30pm on 19 July and into action by 10.00pm. Advances were made, but heavy losses began immediately.

Below is Bill’s description of the battle (with some shortening edits from the original) from a 1992 conversation with Lambis Englezos, AM. Lambis is an amateur historian and school teacher who was responsible for the 2008 discovery of the mass grave near Fromelles, with hopes the project would be able to identify some of the many “lost” soldiers. It begins with a correction to Lambis’ reference to the trenches.

Bill - No they were not trenches, they were sandbagged barricades about 6 feet deep, width, and 6-7 feet high. You see, in the wintertime it was so wet and muddy that you couldn’t have trenches dug out as the word trench means. The enemy had the same of course.

Lambis - But were you confident of taking the Sugarloaf, considering the barrage that had gone over the top?

Bill – Well, my job was to help dig a communication trench across from our own lines to theirs. And the instructions were that when a man in front of you fell who was badly wounded or dead, you just rolled him to one side - to the side that most of the fire appeared to be coming from - of course, this was in the dark, and we didn’t have very much idea – and put a good heaping of earth over him.

Lambis - And you drew a lot of fire then, digging that sap?

Bill - Oh yes, because once the enemy found out that we were endeavouring to dig a communication trench, and, although it was dark, they had lights going up, and coming down. They turned machine guns on and artillery fire as well and the only thing you could do was just lay yourself flat on the ground until the worst of it was over, then hop in again. And I’ll tell you, you were a trier, you were digging all right, that was for sure.

Bill also described some of the tactics the Germans used.

Lambis - You said something about the Germans flooding the trenches, or flooding the ground?

Bill - They flooded the ground. That was mainly the 59th and 60th Battalions copped that. They were supposed to go and take the front – the first enemy trenches, consolidate them and turn them round and go on to the next line of trenches. But as a matter of fact, there was no second line of trenches. There was only just the sloping up of the hill where they had all their fire power up on the top of it and the big water reservoir at the back of that where they had their big pipes coming through to flood the first line of defence. This is what they did, they turned it on. It was getting towards daylight. They were cunning enough to wait until the fellows had to move out, the fellows moved out and tsch!”

And Bill did get wounded in the battle:

Lambis - And you got hit I believe, some shrapnel wounds?

Bill - I got some through the fleshy part of the leg there. We were in a desperate situation, and although I could have said, all right I’m going back to the dressing station, I dressed it myself, the field aid dressings that we all carried, and that was all right. It stiffened up a bit later on. The next day when I examined my tunic – examining is not quite the right word to use I suppose – I was just looking over it, there were a couple of bullet holes through the sleeve there, and through the shoulder strap. You’d marvel that you can go so close and still not get hurt.

Lambis - And your company took heavy casualties did they, in digging that sap?

Bill - Oh yes. What they were I don’t know.

By 6.00am, what was left of the 58th were out of the trenches and they were being relieved by the 57th. Of the approximately 1000 men of the 58th that left Egypt, unit records indicate that the roll call reflected at least 69 killed, 271 wounded and 58 missing.

As he was coming out of the line, Bill saw General Pompey Elliott standing at the head of the sap they had dug. Pompey and Brudenell White had argued against the attack with the British commanders Haking and Gough, in order to buy some more time for undertaking the attack. Bill recalls:

“…it was breaking day when we came in and there was Pompey Elliott standing there with the tears running down his face….. He was very, very upset. He said ‘For God’s sake don’t ever blame me for this’. ‘This is wrong,’ he says, ‘it’s not my fault!’ He was definitely very upset.”

The next several days were spent trying to recover the wounded, under sniper fire, and burying the dead. While there were no further attacks, the 58th remained in the vicinity of Fleurbaix until the end of August.

In mid-August, Bill had developed mumps and was sent to England for treatment but was back in France with his unit by October 1916.

After Fleurbaix, the 58th was moved north towards Belgium, supporting the advance that followed the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line, but did not play a major role.

On 26 August 1917, Bill was promoted to Lance Corporal.

Even More Challenges to Come

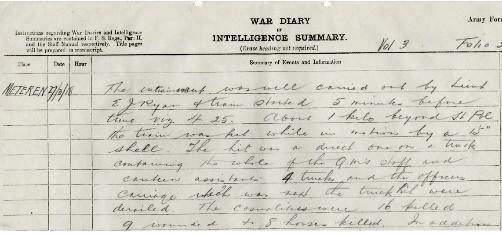

With the collapse of Russia in October 1917, a major German offensive on the Western Front was expected in early 1918. On 27 March 1918, the 58th were moving by train to defend the sector around Corbie, 15 kilometres east of Amiens. Their train was struck by a 16-inch shell and destroyed.

Bill - I was the NCO in charge of the quartermaster’s store, at that particular time. We’d done a forced march from Caestre and then some time after lunch we went to this railway siding. I haven’t the faintest idea where it was, dropped all of our stores on the siding, and the transport officer came along and he said, “Corporal, that’s the only truck you’ve got. You’ve got to put all of your stores into that, and pack them in such a way that you can leave room for 18 men to lie down and have a rest”, because they need the rest. And (this is quite apart from most other things), there was a small body of men left back with a few stores on the siding - never saw them again.

Lambis - Was the train moving at the time or was it stationary?

Bill - It went a few yards and stopped - it was mostly stopped. Later on when I came back from England they told me that the stationmaster at St Pol was a German sympathizer and he held the train there against the signals. I believe he was investigated and then shot by the British.

Lambis - In early discussions you mentioned how you were buzzed by your own planes or something, that they’d been commandeered by the Germans –

Bill - No, no, the Germans had broken through, and they’d captured British observation planes. I’d think they would have been Moths in all probability. They were flying around overhead and we thought they’re having a joyride and, with the situation as it is, why the hell is a man doing a thing like that? He was able to direct the gunfire.

They told me when I eventually got back from England that it was a 16-inch shell. They found enough of the base to measure. It was 16 inches in diameter - it would have weighed a ton according to them. The gun that fired it would have had to have been more than 20 miles away. The first few shells landed short and eventually they got one that went over so, they had a bracket then. All they had to do was aim halfway between there - and there was the target.

Lambis - Do you recall being blown into the air by the blast of the shell?

Bill - I recall everything about it. This is a thing that seems hard to believe because I remember a blinding flash and heat, and the sensation of going upwards. I knew then that a shell had hit us, that something big had hit us, and I’m going up. I thought, when this sensation of going up stops, I’m dead. Then I started to feel myself coming down and I blacked out.

I remember landing on the top of the railway embankment. The train was in an embankment, and I rolled down and I fetched up against the end of the sleepers, conscious of it all and then I blacked out again.

Sometime later, I don’t know how long, a rescue party came along and a chap, an old tent mate from down in Mortlake, name of Jim Cowling. They were coming along with an old kerosene lantern, and I heard suddenly, “Here’s another deady!” and I said, “No Jim, I’m not dead yet!” “Good God” exclaimed the astonished Jim Cowling.

Bill blacked out again. When he regained consciousness, “it was getting daylight and I was on a big grass plot. All around me were a lot of stretcher cases and not a movement in any of them”. It was very cold and he was covered with frost. An orderly walked past and Bill frightened the life out of him by saying, “Hey, mate, could you get me another blanket? I’m cold.” Bill was given blankets and coffee. He was then placed on a hospital train, “cleaned up a bit” and sent to England “to recuperate or die, whichever it was to be”. Bill’s survival was miraculous, and a stark physical reminder followed. “All through my hair was flesh, I was combing the flesh from my hair.” There were 18 men in the shelled carriage and some of the bodies were never recovered.

Bill - One man who was as close to me as what you are there. He’s in this purple cap, and they got him 300 yards away from where the shell had exploded. Now how the hell can a man live through that?

Lambis suggested that he was blessed and that he had a lucky star. Bill just smiled and laughed. The only other survivor of the blast lost a leg and an arm and was repatriated to Australia, where he died two years later. Bill was sent to the City of London Hospital, Clapton, arriving there on 2 April. His luck seemed to hold and his recuperation was such that he was well enough to be sent back to France on 17 July 1918. This was less than four months after being blown sky high.

The end of the War

When the Allies launched their own offensive around Amiens on 8 August, the 58th Battalion was amongst the units in action, although its role in the subsequent advances was limited. The battalion was involved in the fighting to secure Peronne at the beginning of September and entered its last major battle of the war on 29 September 1918.

The battalion withdrew to rest on 2 October and Bill was promoted to Corporal on 11 October 1918.

Weakened by the progressive return of troops to Australia, the battalion was merged with the 59th Battalion on 24 March 1919.

Bill himself returned to Australia aboard the Wyreema on 13 April 1919. His response to being asked what it felt like coming home – “Heaven!”

He was officially discharged on 23 August 1919 having completed more than four years’ service. He was later awarded the British War Medal, 1914-15 Star and the Victory Medal.

After the War

Bill returned to the Warrnambool area and went back to work as a mechanic. However, he said he was dissatisfied with that and he became a grocer’s driver.

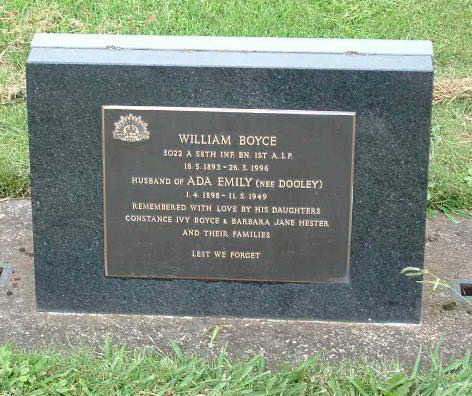

In 1920, he married Ada Emily Dooley, whom he met after the war. They had two daughters and, at the time of the interview, the family had blossomed to 7 grandchildren and 15 great grandchildren.

Bill died of natural causes on 26 March 1996, just shy of 103 years old. He is buried at Colac Lawn Cemetery, Victoria.

Bill’s Reflections

On what War teaches you:

"The main thing is the importance of comradeship. Mates you could absolutely depend on."

On the hardest change of going to war:

“having to be trained to hate the enemy”.

On the benefits of a volunteer army over conscription:

"We could see that the conscript army, the conscript soldier was not the fighter the volunteer was. And why drag a man into it if he doesn't particularly want to come. …and my own feeling on it was this, well, I volunteered to come into it. It’s hell on earth, but why try to drag somebody else into it?”

On identifying his greatest achievement:

"to keep alive".

As summed up by Lambis Englezos -

These words are testament to the rigours, physical and emotional, that Bill Boyce has suffered with quiet dignity.

LEST WE FORGET

Links to Official Records

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).