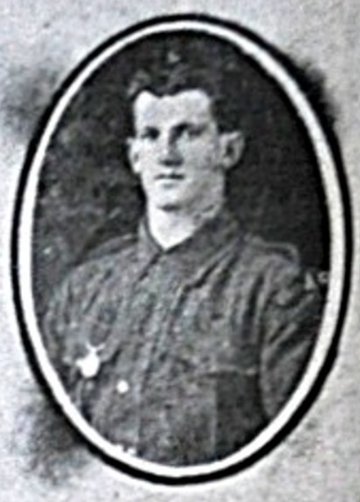

Percy Francis SWINFIELD

Eyes grey, Hair brown, Complexion fair

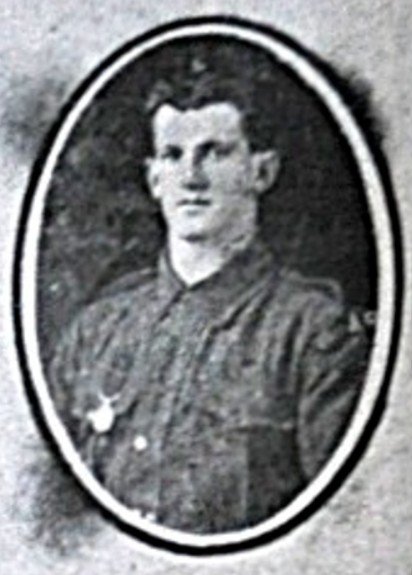

The Swinfield Brothers of Auburn NSW – Jack and Percy

Can you help find Jack?

John ”Jack” Edward Swinfield’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

Jack may be among these remaining unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in Auburn/Sydney, NSW.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for Jack, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Early Life

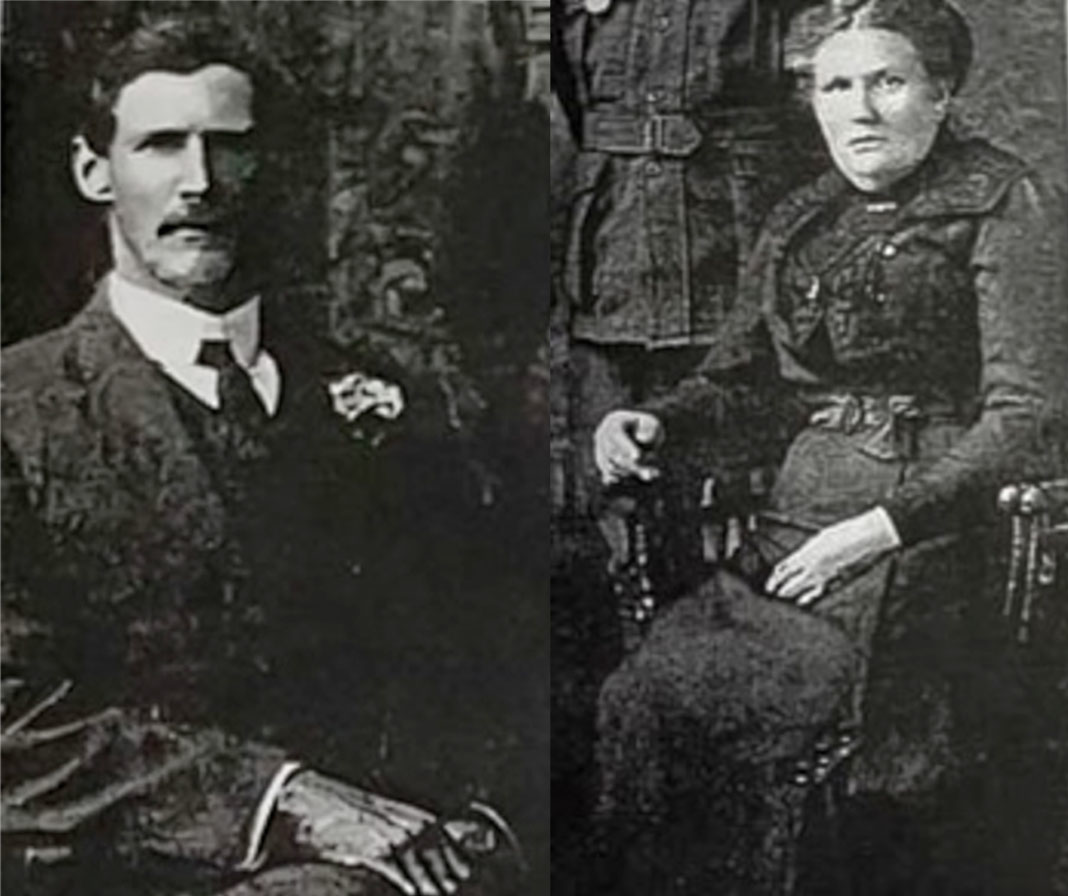

John Edward “Jack” Swinfield and his younger brother Percy Francis Swinfield were the third and fourth children of Albert William Swinfield and Alice Bulpitt, born in Granville and Auburn, New South Wales, respectively. Jack’s paternal grandparents, John Swinfield and Ellen Sophia Burrows, had emigrated from England to New South Wales:

- Albert Oliver William (1891–1967)

- Adelaide Elizabeth (1892–1969)

- John “Jack” Edward (1893-1916)

- Percy Francis (1895–1954)

- Harold (1903–1976)

- Gladys (1909–1909)

The family lived at 104 Harrow Road, a modest, but busy household near the railway line. Jack’s father, Albert, served as Alderman for the Municipality of Auburn. The children grew up during a period of rapid industrial expansion on Sydney’s western fringe. The Swinfield boys attended the Auburn Boys Public School. Both Jack and Percy appear on the school’s wartime Honour Roll.

Jack was mechanically minded and accustomed to hard physical work and he trained as a plumber. Percy worked as a labourer.

Off to War

Jack and Percy enlisted within days of one another in August 1915 at Holsworthy, New South Wales, joining the newly raised reinforcements for the 17th Battalion. Both men embarked from Sydney aboard HMAT A29 Suevic on 20 December 1915, bound for Egypt — two brothers side by side on their first great adventure abroad. A send off for both boys was held just prior to departure:

At the end of last week about a hundred friends of Mr. and Mrs. Swinfield, of Harrow-road, Auburn, and family gathered at the Cosmopolitan Hall to give a send-off to their sons, Percy and John, who have enlisted for the front. On behalf of the gathering, Alderman W. Peat presented John with a sheepskin vest, fountain pen, pipe and wristlet watch, and Percy with a wristlet watch, fountain-pen, pipe and safety razor. Privates R. Finley, W. Finley and H. Jones were included in the send-off. Dancing was indulged in till midnight.

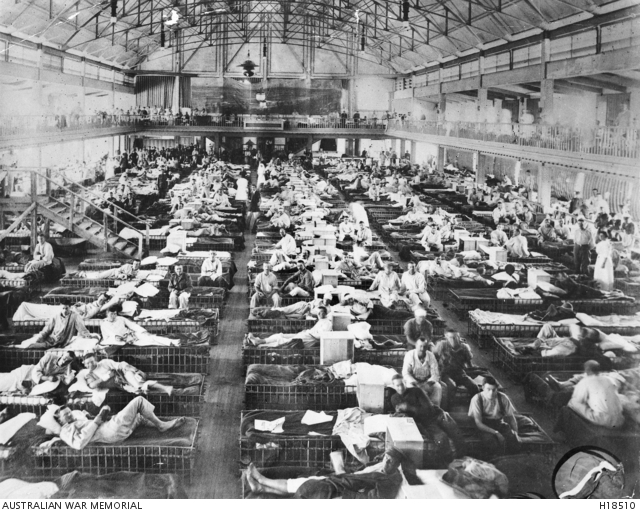

After the month-long trip, as the boys were arriving in Egypt, the new recruits were swarming the camps. The training camp at Tel-el-Kebir, which was about 110 km north-east of Cairo, contained around 40,000 Gallipoli veterans and the thousands of reinforcements arriving regularly from Australia. In February 1916, influenza was sweeping through the camp and Jack was sent to the 1st Australian Auxiliary Hospital in Heliopolis from 9 to 17 February, after which he returned to the 17th Battalion.

At the same time, the Australian Imperial Force was undergoing major reorganisation as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five. On 16 February 1916 the 53rd Battalion was formed, drawing its experienced core from the 1st Battalion’s Gallipoli veterans, reinforced by new men from Australia. Jack was transferred to the 53rd Battalion in early April, part of the 14th Brigade, 5th Australian Division, and issued a new regimental number, 3297A. The Gallipoli men were quick to distinguish themselves from the reinforcements, calling themselves the “Dinkums” and the newer arrivals the “War Babies”.

Source - AWM4 23/70/1, 53rd Battalion War Diary, Feb–July 1916, p. 3

Jack trained intensively in the desert heat at Tel-el-Kebir. His reliability and steady conduct were recognised with a temporary promotion to Lance Corporal during the training period prior to embarkation for France. Percy’s path diverged during this reorganisation. In mid-February 1916 he was transferred briefly to the newly formed 55th Battalion of the 15th Brigade. Soon after, he was reassigned from the infantry to the artillery and taken on strength of the 13th Field Artillery Brigade. He was posted to the 59th Battery, initially serving as a Gunner before being appointed Driver in April 1916.

Drivers played a vital role in keeping the guns supplied and mobile under fire, handling teams of horses, ammunition limbers, and maintaining communications — often under shelling themselves. On 16 June 1916, the 53rd Battalion began its move to the Western Front. Thirty-two officers and 958 men left Alexandria aboard HMT Royal George on 19 June, arriving at Marseilles on 28 June. They were immediately entrained for a 62-hour journey north to Hazebrouck, before marching into camp at Thiennes in northern France. Along the way, the battalion noted that their “reputation had evidently preceded them”, receiving a warm welcome from civilians in towns along the route.

Source AWM4 23/70/2, 53rd Battalion War Diary, Feb–June 1916, p. 4

The area around Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” — a supposedly quiet stretch of the line where inexperienced troops were introduced to trench warfare. In reality, conditions were harsh. Rain flooded communication trenches, artillery fire harassed supply routes, and men lived and worked amid mud, barbed wire, and constant danger. On 8 July 1916, the 53rd Battalion began a 30-kilometre march to Fleurbaix. Two days later, they entered the trenches for the first time.

By early July, both Swinfield brothers were serving in the same sector. Jack’s battalion occupied the front-line trenches near Fromelles, while Percy’s battery dug gun pits behind the line, preparing to support the infantry in what would soon become the 5th Division’s first major battle on the Western Front — one brother in the assault trenches, the other behind the guns that would thunder overhead in support.

Battle of Fromelles

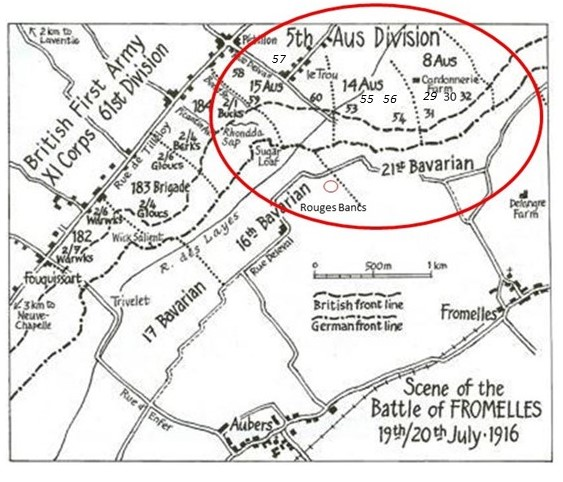

The main objective for the 53rd was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the 53rd and the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfiladed fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 60th and 54th Battalions on their flanks. The men knew something was coming. They rehearsed attacks in replica trench systems, inspected bayonets and watched as huge guns rolled into place behind the lines. Then on 16 July, they moved up for an attack—only to have it postponed due to weather.

The delay proved torturous. Private Jim Granger (4784), a young Dorrigo soldier, described the tension in his dugout:

“We were held in suspense for three days… like a criminal waiting to hear the verdict. We had no dugouts where we were in the supports and shrapnel was bursting all round.”

On the 19th, heavy bombardment, with Percy’s support, was underway from both armies by 11.00 AM. At 4.00 PM the 54th Battalion rejoined on their left. All were now in position for battle. Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. The Australians went on the offensive at 5.43 PM.

They moved forward in four waves – half of A & B Companies in each of the first two waves and half of Jack’s C Company & D Company in the third and fourth. They did not immediately charge the German lines, they went out into No-Man’s-Land and lay down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift.

Private Arthur Crewes (4755) wrote of the time:

“At 5.43 pm the signal for the charge sounded, and over the top we went into the face of death, shells bursting, machine guns rattling and rifles crackling.”

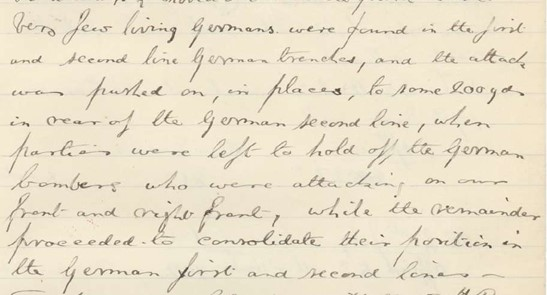

At 6.00 PM the German lines were rushed. The 53rd were under heavy artillery, machine gun and rifle fire, but were able to advance rapidly. As below, the 14th Brigade War Diary notes that the artillery had been successful and “very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches”, but within the first 20 minutes the 53rd lost ALL the company commanders, ALL their seconds in command and six junior officers.

Source: AWM C E W Bean, The AIF in France, Vol 3, Chapter XII, pg 369

Some of the advanced trenches were just water filled ditches, which needed to be fortified by the 53rd to be able to hold their advanced position against future attacks. They were able to link up with the 54th on their left and, with the 31st and 32nd, occupied a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm. But the 60th on their right had been unable to advance due to the devastation from the machine gun emplacement at the Sugar Loaf. They held their lines through the night against “violent” attacks from the Germans from the front, but their exposed right flank had allowed the Germans access to the first line trench BEHIND the 53rd, requiring the Australians to later have to fight their way back to their own lines. By 9.00 AM on the 20th, the 53rd received orders to retreat from positions won and by 9.30 AM they had “retired with very heavy loss”.

Source: AWM4 23/70/2 53rd Battalion War Diaries July 1916 page 7

Of the 990 men who had left Alexandria just weeks before, the initial count at roll call was 36 killed, 353 wounded and 236 missing:

“Many heroic actions were performed.”

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The final impact of the battle on the 53rd was 245 soldiers were killed or died from their wounds and, of this, 190 were not able to be identified.

After the Battle

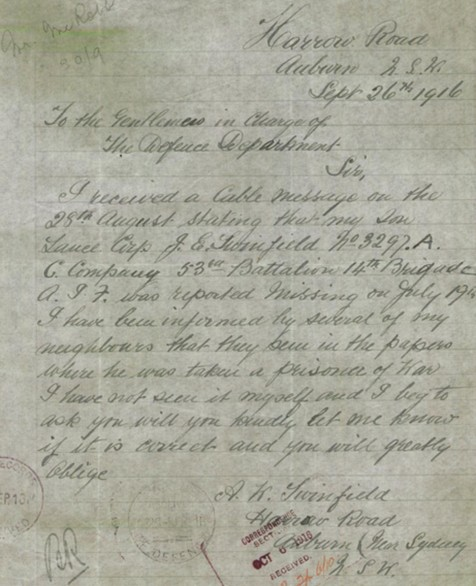

Percy had been under heavy fire throughout the battle, but he did survive. In his small unit, Captain G.K. Thompson and four soldiers were killed and Lieutenant W.E. Cox and two soldiers had been wounded. Jack, however, was among the many “missing” from the battle. The family was advised of this, but no details were available to be provided. There was a rumor that Jack had been taken prisoner and Jack’s father, Albert, wrote to the Defence Department on 26 September 1916, seeking confirmation of this:

“I received a cable message on the 28th August stating that my son Lance Corporal J. E. Swinfield, No. 3297, A Company, 53rd Battalion, 14th Brigade, A.I.F., was reported missing on July 19th. I have been informed through my neighbours that they saw in the papers where he was taken a prisoner of war. I have not seen it myself and I beg to ask you will you kindly let me know if it is correct and you will greatly oblige.— A. W. Swinfield, Harrow Road, Auburn N.S.W.”

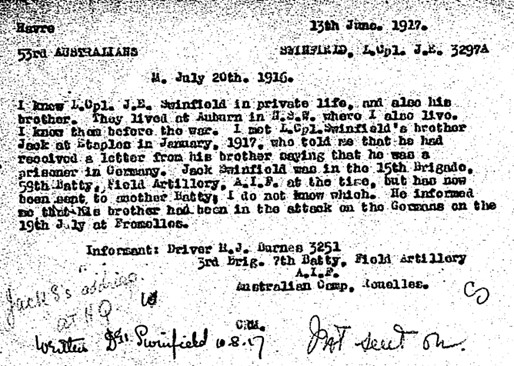

However, news was, at best, sparse and no confirmation for Arthur’s request was sent. The Army and the Red Cross did continue their searches for the missing. In mid-June 1917, a report from Driver M Burnes (3251) (ed. corrected from Red Cross Witness Statement), who knew Jack and had met with Percy in January 1917, kept hopes alive that Jack was a POW.

Unfortunately, this turned out to not be true, as Percy replied in October 1917:

“Sorry to say the last I saw or heard of him was going into the line on the 19th of July 1916. I have been enquiring at his Battn but no result.”

On 26 September 1917, Base Records advised the family:

“I regret to have to inform you that no further official news has yet been received of No. 3297 L/Cpl J. E. Swinfield, 53rd Battalion, who was reported missing on 19th July 1916.”

A Court of Enquiry in the Field on 31 December 1917 formally concluded that Jack had been Killed in Action on 19 July 1916. After the War the Army was still seeking information about the missing soldiers and contacted the families to see if they had ever come across more information. Alice replied on 7 August 1921, realistic, but still hopeful that some degree of closure might still be possible:

“We have no correspondence that would likely give any information concerning my son’s death. … The Battle was fought at Fleurbaix on the 19 July 1916 and he was seen for only a couple of minutes after he went over.” She went on to identify his Jack’s corporal, J. Morris, who has returned to Australia and Alice believed he lived at Forest Lodge, Sydney.

There are no records about any contact being made with the soldier Alice had identified. No closure for Alice or the family. Jack’s loss was remembered in memorial notices long after his death:

“My dear son and brother sleeps his last long sleepIn a grave I may never see;May some kind hand in that far-off landStrew some flowers for me.”— Inserted by his loving mother, father and brothers, A. O. W., Driver Percy F., and Harold Swinfield.

Jack received the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll. He is commemorated at:

- Auburn Boys Public School Honour Roll

- Municipality of Auburn Roll of Honour

- Australian War Memorial in Canberra

- VC Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial

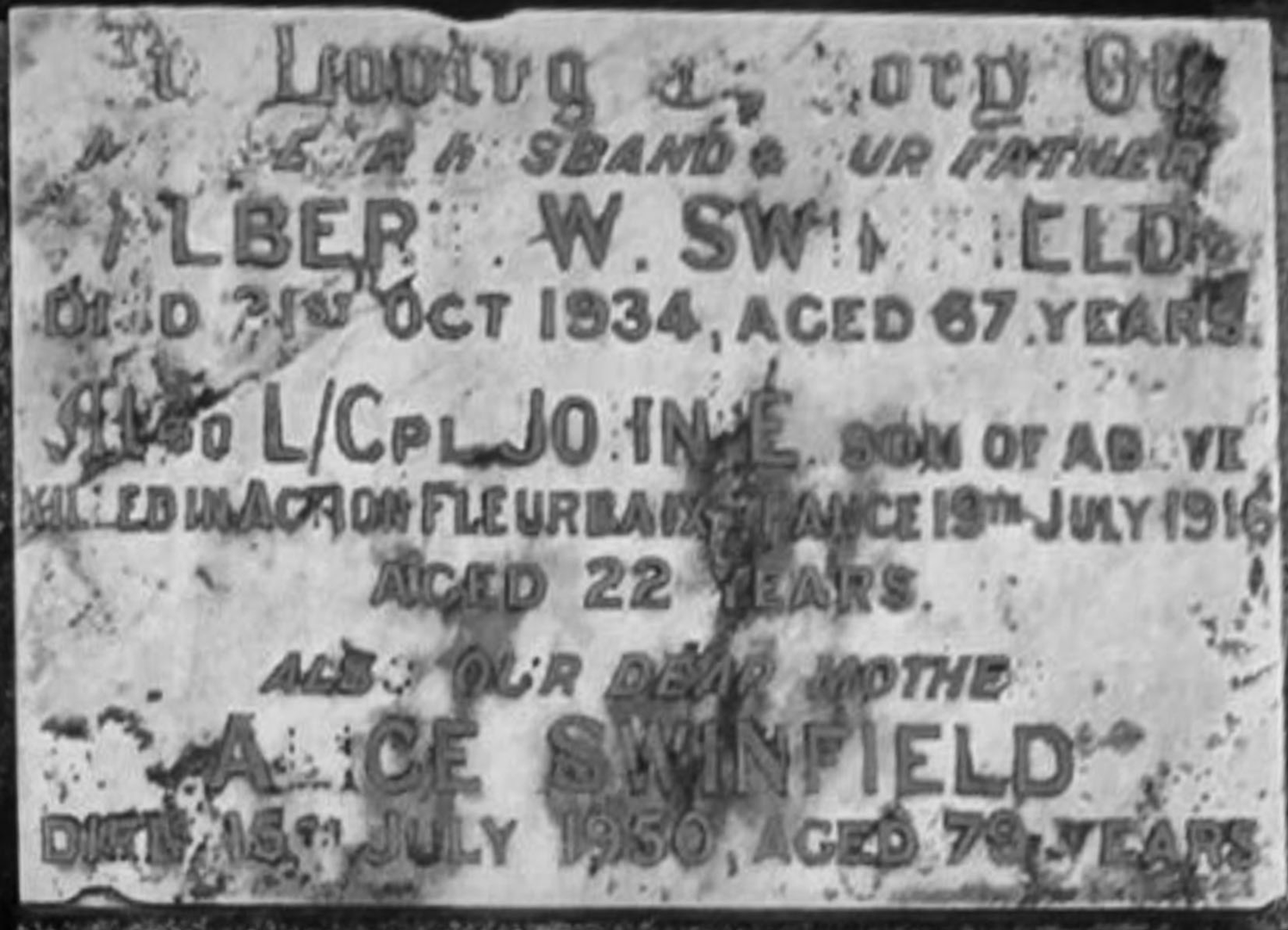

While he has no grave of his own, his name was later inscribed on the family headstone in Rookwood Cemetery, alongside his parents Albert and Alice.

Percy returned safely to Australia aboard the Boonah, disembarking in Sydney on 5 July 1919. After four years of war service, he resumed civilian life in Auburn, where he worked as a labourer and later lived at Cumberland Road, Auburn. He married Hilda Saunders and they had 4 children. He died on 29 July 1954, aged 58.

Finding Jack

Jack’s remains were not recovered; he has no known grave. After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including 15 of the 190 unidentified soldiers from the 53rd Battalion.

We welcome all branches of Jack’s family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in Auburn/Sydney, NSW. If you know anything of family contacts, please contact the Fromelles Association. We hope that one day Jack will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Jack’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Lance Corporal John Edward “Jack” Swinfield (1894–1916) (birth registered as John Edward Swinfield, Central Cumberland) |

| Parents | Albert William Swinfield (1866–1934) and Alice Bulpitt (1871–1950) |

| Siblings | Albert Oliver William Swinfield (1891–1967) | ||

| Adelaide Elizabeth Swinfield (1892–1969) | |||

| Percy Francis Swinfield (1895–1954), married Hilda Saunders | |||

| Harold Swinfield (1903–1976) | |||

| Gladys Swinfield (1909–1909) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | John Swinfield (c.1835–1911) and Ellen Burrows (c.1836–1908) | ||

| Maternal | James Bulpitt (1842–1909) and Sarah Ann George (1843–1920) |

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).