Richard Roland COADY

Eyes brown, Hair grey, Complexion fair

Richard Coady - A father who never came home

Can you help us identify Richard?

Richard’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and he has no known grave. It is highly likely that he was one of the soldiers buried by German forces in the mass grave behind Pheasant Wood, discovered in 2008. As of 2025, Richard Coady has not yet been identified, but DNA testing has successfully named 180 of the 250 soldiers recovered from that site.

We are now seeking DNA donors from Richard’s extended family. If you are a relative or descendant, your DNA could be the key to identification, please see the DNA box at the end of this story.

Richard Coady, who enlisted as Roland Coady, was born in 1869 in Sydney, New South Wales. He was one of six children of Irish-Australian parents Richard Coady (1833–1898) and Mary Skinners (1835–1887).

The Children of Richard and Mary:

- James Coady (1864–1938), married Annie

- Jane Coady (1866–1867)

- Richard Coady (1869–1916), married Elizabeth Winders

- William Coady (1871–1920), married Rosanna Smally

- John James Coady (1876–1923), married Ada Maria Roberts and later Margaret Graham

- Mary Ellen Coady (1882–1961), married Herbert John King

Richard’s late teenage years were marked by personal loss and frequent contact with the law. His father and his brothers were all well known to the local constabulary. In 1887, when Richard was about 18, his mother Mary passed away. Around the same time, Richard appeared in the NSW Gaol Description and Entrance Books multiple times. At 17, he was sentenced to five months for obscene language and assaulting a constable. This was followed by a seven-day sentence for riotous behaviour in 1887, and a further 14-day term in 1888 for resisting arrest.

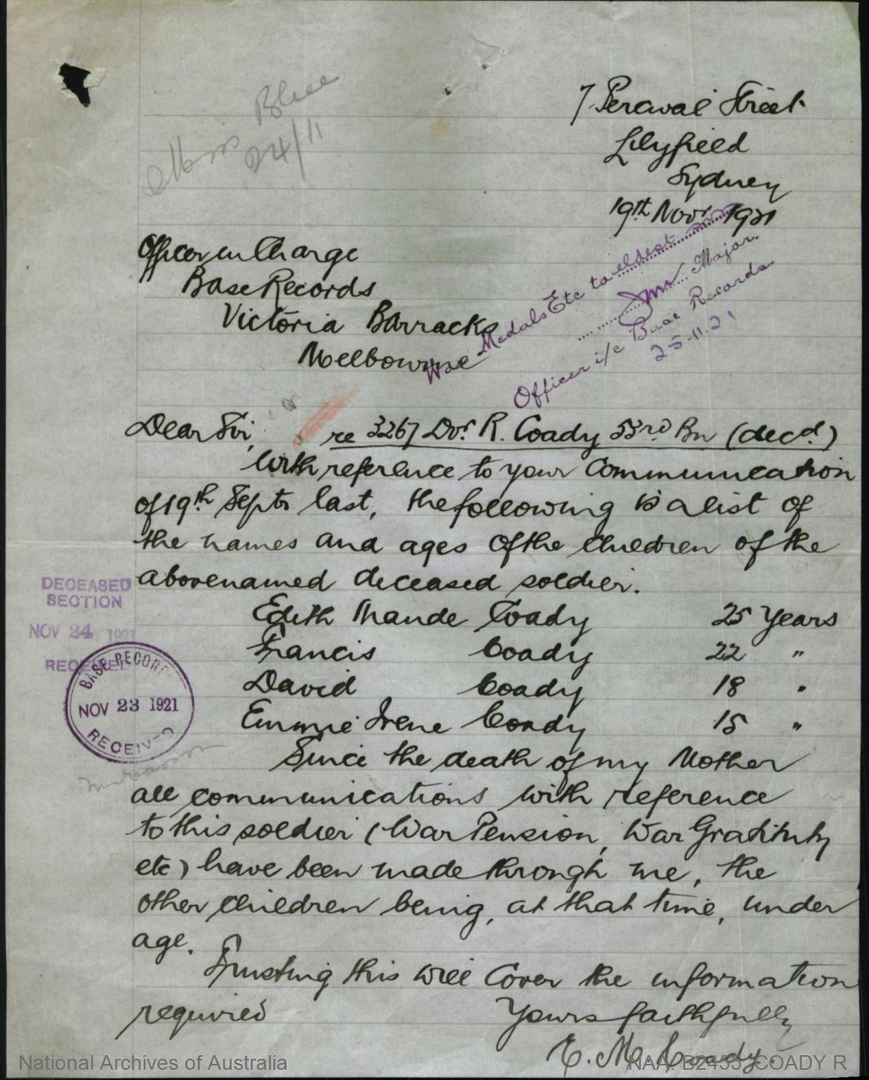

In 1891, at age 22, Richard married Elizabeth Winders, a 24-year-old domestic servant, in Balmain North. The couple settled in Crescent Street, Balmain, before moving to Marrickville, and later to Cleveland Street, Sydney. They had six children:

- Richard David Coady (1893–1913)

- Edith Aurila Maud Coady (1896–1980), married Charles Richard

- Albert James Coady (1897–1971), AIF, married Gladys Pert

- Francis Coady (1900–1963), married Mary Boggle

- David Coady (1903–1993), married Gladys Moore

- Emmie Irene Coady (1906–1925)

In June 1906, Richard was charged with wife desertion when the children were young. They later reconciled. The family experienced tragedy in 1913 when their eldest son, Richard David, died at the age of 20. Despite his troubled early adulthood, Richard eventually settled into work as a horse driver, working for many years at the Glebe abattoirs, carting butcher’s carcasses through Sydney’s inner suburbs.

Enlistment and Training

On 12 July 1915, Richard Coady enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force at Warwick Farm, New South Wales. Though his birth name was Richard, he enlisted under the name Roland Coady, possibly to present a new identity or to reflect a preferred middle name. At the time, he was 46 years old and gave his occupation as a horse driver. He nominated his wife, Elizabeth Coady, of 22 Wentworth Street, Glebe, as his next of kin. Richard was assigned to the 3rd Battalion, 11th Reinforcements.

After basic training, he embarked from Sydney on 2 November 1915 aboard HMAT A14 Euripides bound for Egypt. Like many new recruits arriving late in 1915, he was caught up in the rapid reorganisation of the AIF following the Gallipoli campaign. While in Egypt, he was transferred to the newly formed 53rd Battalion, part of the 14th Brigade in the 5th Australian Division. Training in Egypt was intense but brief. The AIF was undergoing a rapid expansion to meet the needs of the Western Front, and battalions were being formed and deployed in quick succession.

Richard’s new unit, the 53rd Battalion, would soon be sent to France — and within weeks of arrival, into their first major battle. On 8 July 1916, the 53rd Battalion began a 30 km march to Fleurbaix and were settled into billets there on 16 July. Among them was Richard, who had only recently arrived on the Western Front after training in Egypt. Early the next morning, the battalion was moved straight into the front lines for an attack, but it was cancelled due to bad weather. The 53rd remained in the trenches in relief of the 54th Battalion, enduring constant enemy fire, wet conditions, and tension as preparations resumed.

The Battle of Fromelles

“we took three lines of German Trenches”

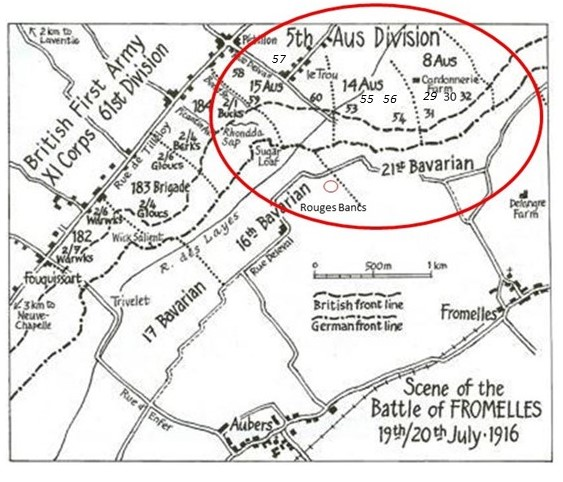

On the 19th of July, heavy bombardment was underway from both armies by 11.00 AM. At 4.00 PM the 54th rejoined on their left. All battalions were now in position for battle. The Zero Hour for advancing from the front-line trenches was set for 5.45 PM, but the Germans were well aware of the impending attack. At 5.15 PM, they launched a massive artillery bombardment on the Australian trenches, causing chaos and inflicting significant casualties before the Australians had even begun their charge.

The main objective for the 53rd was to take the trenches to the left of the heavily fortified and elevated German defensive position known as the “Sugar Loaf”, which dominated the front lines. This strongpoint posed a deadly threat — if it could not be taken, the 53rd and their supporting units would be exposed to murderous enfiladed fire and German counterattacks from that flank. As they advanced, the 53rd were to link up with the 60th and 54th Battalions on their flanks.

Only three of the men shown here survived the action and those three were wounded

The Australians launched their offensive at 5.43 PM. The men moved forward in four waves: half of A and B Companies in the first two waves, and half of C and D Companies in the third and fourth. They did not immediately rush the German trenches but instead went out into No-Man’s-Land and lay down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift. At 6.00 PM, the order came to charge. The 53rd were immediately hit by heavy artillery, machine-gun, and rifle fire, but managed to advance rapidly. Corporal John T. James of C Company (3550) later reported:

“At Fleurbaix on the 19th July we were attacking at 6 p.m. We took three lines of German trenches.”

The 14th Brigade War Diary observed that the artillery had been largely effective and “very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches”, but the cost was terrible. Within the first 20 minutes, the 53rd Battalion lost all of its company commanders, all seconds-in-command, and six junior officers. Source: AWM C.E.W. Bean, The AIF in France, Vol 3, Chapter XII, p. 369

Some of the captured trenches were little more than waterlogged ditches. These had to be hastily fortified by the 53rd to defend against inevitable German counterattacks. They were able to link up with the 54th on the left and, with the 31st and 32nd Battalions, occupy a rough line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm. However, the 60th on their right had been unable to advance due to the ferocity of machine-gun fire from the Sugar Loaf. Throughout the night, the 53rd held their lines against “violent” counterattacks. However, their right flank was exposed, allowing German troops to re-enter parts of the Australian first line trench behind them.

By 9.00 AM on 20 July, the order was given to retreat, and by 9.30 AM, the 53rd had withdrawn — "suffering very heavy losses."

Source: AWM4 23/70/2, 53rd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, p. 7.

Of the 990 men who had left Alexandria just weeks before, the initial post-battle count revealed 36 killed, 353 wounded, and 236 missing. Later records confirmed that 245 men of the 53rd Battalion were killed or died of wounds, of whom 190 were not able to be identified.

Source: AWM4 23/70/2, 53rd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, p. 8

Richard was among those reported killed in action.

Aftermath

In the days following the Battle of Fromelles, confusion reigned. The dead lay scattered across No-Man’s-Land, and many wounded were left behind. The Australians had suffered more than 5,500 casualties in a single night, and for families back home, news was slow and devastating. Richard was reported Killed in Action on 19 July 1916, but no details were given in the immediate aftermath.

His name did not appear on German death lists, and there were no Red Cross witness statements confirming the circumstances of his death or burial. Like hundreds of others, he had simply vanished.

His wife Elizabeth Coady and their children — Edith, Frank, Dave, and Emmie — placed a memorial notice in The Sydney Morning Herald in September 1916. Their grief was captured in a simple verse:

He fought for those he loved so dear,

That we may all live free.

And on the battlefields of France

Gave his life for you and me.

These simple words from a grieving family ensured that Richard’s sacrifice would not be forgotten.

His name is inscribed on the VC Corner Australian Cemetery Memorial in Fromelles, France, which bears the names of 1,299 Australians who were killed in the battle and have no known grave. This stark and solemn memorial stands close to where Richard and his mates fought and fell in July 1916.

In Australia, his name appears on the Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour in Canberra, under Panel 156. It is listed alongside the thousands of Australians who served and died in the Great War.

Where was Albert?

Richard’s son, Albert James Coady, followed in his father’s footsteps, enlisting just one day after Richard, on 13 July 1915. At the time, Albert was 21 years old, married to Gladys Pert, and living at 19 Mount Vernon Street, Forest Lodge. Like his father, he worked as a horse driver.

Initially, he became 1075 Trooper Albert Coady, assigned to the 5th Reinforcements, 12th Battalion, later transferring to the 10th Reinforcements, 7th Light Horse Regiment. However, Albert struggled with military discipline in those early days, with several charges for being Absent Without Leave (AWL) and other minor offences. Before embarking overseas, he was discharged.

But Albert’s military story did not end there.

In August 1916, after learning that his father was missing in action at Fromelles, Albert re-enlisted under the name Richard James Coady, becoming 3086 Private Coady, 1st Pioneer Battalion. He embarked on 17 October 1916, disembarking at Plymouth on 9 January 1917. During the voyage, he was charged with gambling and reduced to private. It was not until March 1918 that he finally arrived in France.

His time on the Western Front was marked by disciplinary issues. On 2 May 1918, he faced a Court Martial, presided over by Sir William McCay, a senior Australian general. Despite these setbacks, Albert served until April 1919, was discharged in November 1919, and returned to Australia on 29 February 1920. Due to his conduct record, he returned without medals and with five years of remaining penalties to serve.

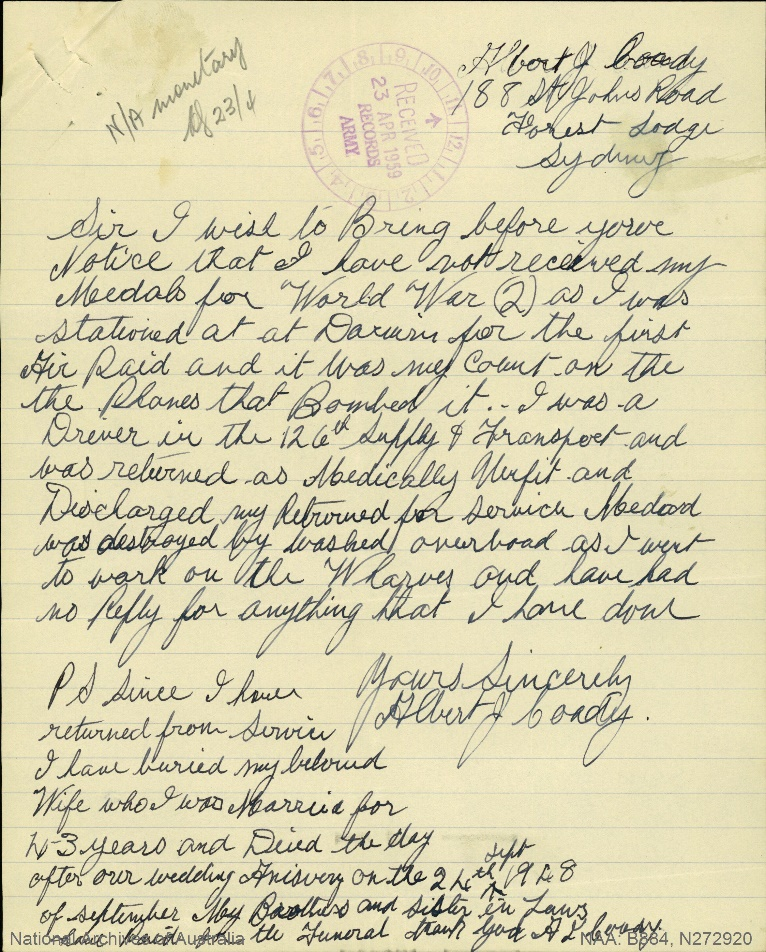

Albert did not give up on service. During World War II, he enlisted again, joining the Military Reserve Motor Transport Company. He was stationed in Darwin during the Japanese bombing raids of 1942, and later wrote:

“I was stationed at at Darwin for the first air raid and it was my count on the planes that bombed it. I was a Driver in the 12th Supply & Transport and was returned as Medically Unfit and discharged.”

Despite his hardships, Albert and Gladys built a family together and raised two children. Sadly, Gladys passed away in September 1948, the day after their 35th wedding anniversary, a loss that deeply affected him. Albert wrote of his grief:

“Since I have returned from service I have buried my beloved wife who I was married for 35 years and died the day after our wedding anniversary. My brothers and sister in laws attended the funeral at Field of Mars.”

By 1968, Albert was living at 104 Glebe Point Road, Glebe, recorded as a widower. He died in June 1971, aged 74, and was buried at Field of Mars Cemetery, East Ryde, in Section R, Plot 138A. Albert’s life was marked by two wars, personal challenges, and enduring grief, but also by love, family, and resilience. His story, like Richard’s, is part of the broader Coady family legacy of service and sacrifice.

Can you help us identify Richard?

Richard’s body was never recovered after the Battle of Fromelles, and he has no known grave. In 2008, a mass grave was discovered behind Pheasant Wood, containing the remains of 250 Australian and British soldiers buried by German forces after the battle. DNA testing has successfully named 180 of the soldiers found so far. We are now seeking DNA donors from Richard’s extended family — particularly from the maternal lines — to help confirm his identity. If you are a relative or descendant, your DNA could be the key to finding Richard.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Richard Coady (1869–1916) |

| Parents | Richard Coady (1833–1898) and Mary Skinners (1835–1887) |

| Siblings | James Coady (1864–1938) | ||

| Jane Coady (1866–1867) | |||

| William Coady (1871–1920) | |||

| John James Coady (1876–1923) | |||

| Mary Ellen Coady (1882–1961) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | James Coady (1814–1892) and Bridget McGrath (1816–1875) | ||

| Maternal | unknown |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).