Percy BAKER

Eyes grey, Hair dark brown, Complexion medium

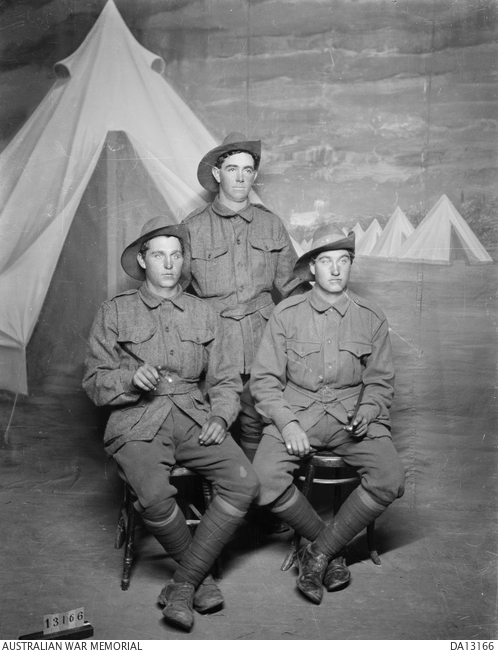

Percy, Hughie and Charlie – Three Terang Mates Who Enlisted Together

Can you help find Percy?

Percy Baker’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

Percy may be among these remaining unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in Colac, VIC, and the Baker family ancestors in Somerset.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for Percy, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Early Life

Percy Baker was born in 1893 at Colac, Victoria, the second son of Henry (Harry) Baker and Mary Jane Menzies Spencer. His younger brother Hugh (“Hughie”) was born two years later, on 16 June 1895. Their other children were Bertie, Kezia Jane and Mary Elizabeth. The boys grew up in a large, blended family – two older sisters from Mary Jane’s first marriage, two boys from Harry’s first marriage, the four children of Harry and Mary Jane and later four children from Harry’s third marriage to Annie Elizabeth Stevens, after Mary Jane passed away in 1901. Percy and Hughie’s mother, Mary Jane, had been widowed young. Her first husband, Frederick Walter Lange, died suddenly, leaving her with two small daughters — Catherine Emily (Minnie) Maud Lange and Waltrina Ruth Lange.

Harry’s first wife was Ellen Hunter, who had died in 1888. They had two surviving sons, Robert and Henry. In 1889, Mary Jane married Harry and together they built a new life in Colac. Mary Jane had been born at Pleasant Creek (Stawell), Victoria, the daughter of James Spencer and Catherine Provan Menzies. Harry was born at Duneed, near Geelong, the son of George Baker and Elizabeth Thorogood. Elizabeth was the daughter of a convict while George Baker is well recorded as a convict who arrived in December 1836 at Hobart Town aged 18. He came from Staunton Prior, Somerset. George was pardoned and living in Geelong in 1856 when Harry was born.

Both well recorded through convict records.

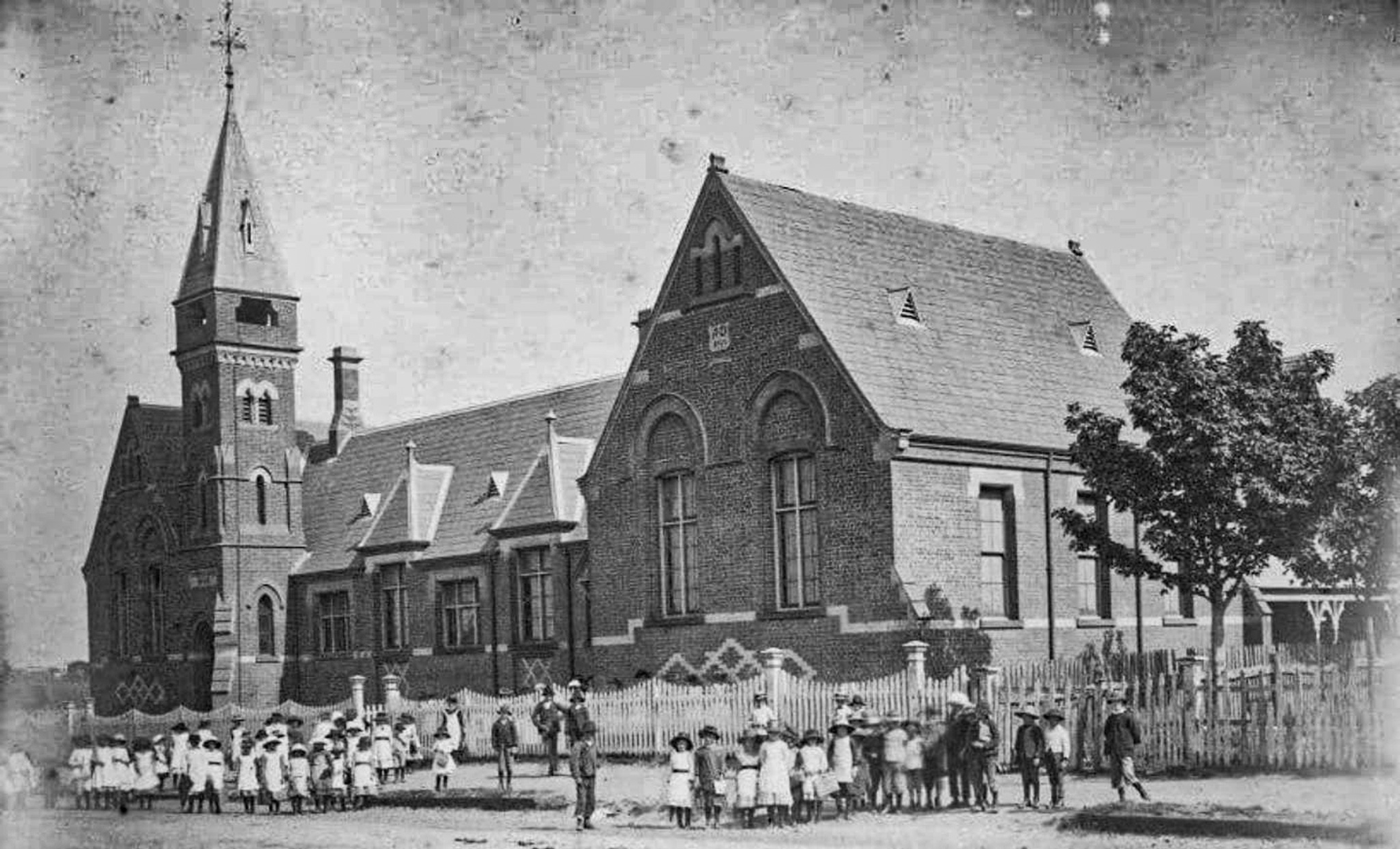

The Baker family were well known in Colac and later in Terang, where Harry worked as a labourer and blacksmith. The children attended Colac State School.

When Mary Jane died in 1901, soon after the birth of her youngest child, Harry was left to raise their children, all of primary school age. Presumably, Mary Jane’s teenage daughters were able to help out. Three years later he married Annie Elizabeth Stevens, to help hold the family together. Henry and Annie then had four children, Violet, Emily, Priscilla and Walter, who died in infancy. By 1915, Percy was 21 and living in Terang, working as a labourer and lodging with friends. He named Miss M. Primmer, of Terang, as his next of kin. Hughie was also working locally.

Off to War

Recruiting in the area had gathered momentum following a public meeting in June, and the enlistees names were published in the Terang Express soon after. Among them were Percy and Hughie and their friend Charles “Charlie” Bannon, a blacksmith’s apprentice from Terang. Recollections on the Virtual War Memorial Australia page for Charlie Bannon describe how the three young men decided to enlist together:

When Hughie — the younger brother — spoke of joining up, their father Harry is said to have told him, “You’d better take your brother with you to keep an eye on you.” Percy agreed, and their mate Charlie Bannon laughed, “Then I’d better go too, to keep an eye on you both.”

And so the three Terang boys travelled to Melbourne in July 1915 and enlisted almost side by side, their regimental numbers stamped in sequence by the recruiting clerk -3453 (Percy), 3454 (Hughie), and 3456 (Charlie) — confirmed that they enlisted together. They were assigned to the 21st Battalion, 8th Reinforcements.

After their training at the Broadmeadows camp outside of Melbourne, they embarked aboard HMAT A64 Demosthenes from Melbourne on 29 December 1915, for the month+ trip to the training camps in Egypt. With the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five, major reorganisations were underway. All three remained in the 15th Brigade, but Percy and Hughie ended up in the newly formed 59th Battalion, and in the same Company, but Charlie was assigned to the 60th.

The 59th Battalion had been raised in Egypt on 21 February 1916 at the 40,000-man training camp at Tel-el-Kebir, about 110 km northeast of Cairo. Approximately half of its recruits came from the 7th Battalion Gallipoli veterans and the other half from reinforcements from Australia. The 59th was predominantly composed of men from rural Victoria. After a month of training at the large camp at Tel- el-Kebir, Percy and Hughie had a two+ day, 50 km march in thermometer-bursting heat across the Egyptian sands from Tel-el-Kebir to Ferry Post, near the Suez Canal. Prior to marching, only ½ pint of water per bottle was available.

Source- AWM4 23/15/1 15th Brigade War Diaries Feb-Mar 1916 p 6.

A month later they were relieved and headed for the camp at Duntroon Plateau. It was not all work, however. A 5th Division Sports Championship was held on 14 June, which was won the by the 59th’s 15th brigade. The very next day they began preparations for heading to the Western Front. The 59th, along with Charlie’s 60th, departed aboard the Kinfauns Castle from Alexandria on 18 June 1916. After a brief stop in Malta, the 59th disembarked at 7.00 AM in Marseilles on 29 June. By 10.00 PM they were on a train headed for Steenbeque, 35 km from Fleurbaix in northern France, arriving on 2 July.

This area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. Training continued, but with a higher sense of urgency, and it now included the use of gas masks and learning to deal with the effects of large shells. The move to the front continued. On 9 July they were in Sailly sur la Lys, just 1000 yards from the trenches. At 4.00 PM on 18 July 1916, the 59th Battalion entered the front-line trenches relieving the 57th.

The Battle of Fromelles

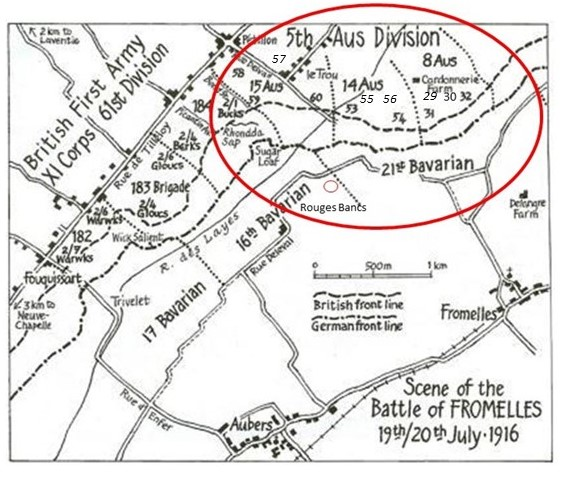

The battle plan had the 15th Brigade located just to the left of the British Army. The 59th and 60th Battalions were to be the lead units for this area of the attack, with the 58th and 57th as the ‘third and fourth’ battalions, in reserve. The main objective for the 15th Brigade was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfilade fire from the machine-guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 60th battalion and the British on their flanks.

The main attack against the Sugar Loaf position was planned for 17 July, but it was delayed due to bad weather. On 19 July, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. A fellow soldier, Bill Boyce (3022, 15th Brigade, 58th), summed the situation up well,

“What have I let myself in for?”

Source - Australian War Memorial Collection C386815

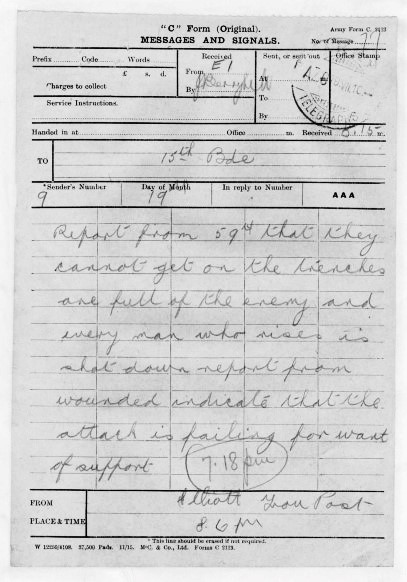

Their attack on the German lines began at 5.45 PM on the 19th. The 59th went over their parapet in four waves at 5 minute intervals, but then laid down to wait for the support bombardment to end at 6.00 PM. A & B Companies were in the first two waves, C & D in the next two. There was immediate and intense fire from rifles and the Sugar Loaf machine guns. As documented in the messages sent back to HQ just after the attacks began:

“cannot get on the trenches as they are full of the enemy”

“every man who rises is shot down”

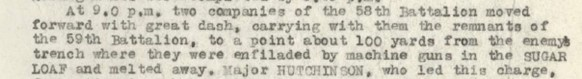

“‘they were enfiladed by machine guns in the Sugar Loaf and melted away”

The British 184th Brigade just to the right of the 59th met with the same resistance, but at 8.00 PM they got orders that no further attacks would take place that night. However, the salient between the troops limited communications, leaving the Australians to continue without British support from their now exposed right flank. The official reports indicate advances against the Sugar Loaf fortification were limited, but individuals’ reports suggest that some did reach the German parapet. However, their gains were impossible to hold and with little support being available they had to drop back.

The attack was ended early on the morning of the 20th. At the 8 AM roll call, out of a battalion of about 1000 soldiers, 4 officers and 90 other ranks reported in. While there was no cease fire after the battle, parties did go to No-Man’s Land to bring back wounded soldiers, with over 200 were recovered on 20 July. The initial toll on the 59th was 26 killed or died of wounds, 394 were wounded and 274 were missing – 694 soldiers. Ultimately, 334 soldiers were killed in action or died from their wounds from this battle. 239 of the soldiers were unidentified.

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield.

After the Battle

Percy and Charlie were not among those at their unit’s roll calls, but at least Hughie was. Percy was listed as missing in action and for months his family could learn nothing else of his fate. Percy’s stepmother, Ann Baker, wrote to Base Records desperate for news. On 9 October 1916 she wrote:

“We don’t know whether he is wounded or taken prisoner or not. I hope we have some news of him soon as we are very uneasy about him.”

In the same letter, she thanked the authorities for informing her that Hugh, Percy’s younger brother, had been wounded in the chest and was in hospital in England.

“Hoping you will find out about my stepson Percy Baker, same company as Hugh Baker 3453 –59th Batt.”

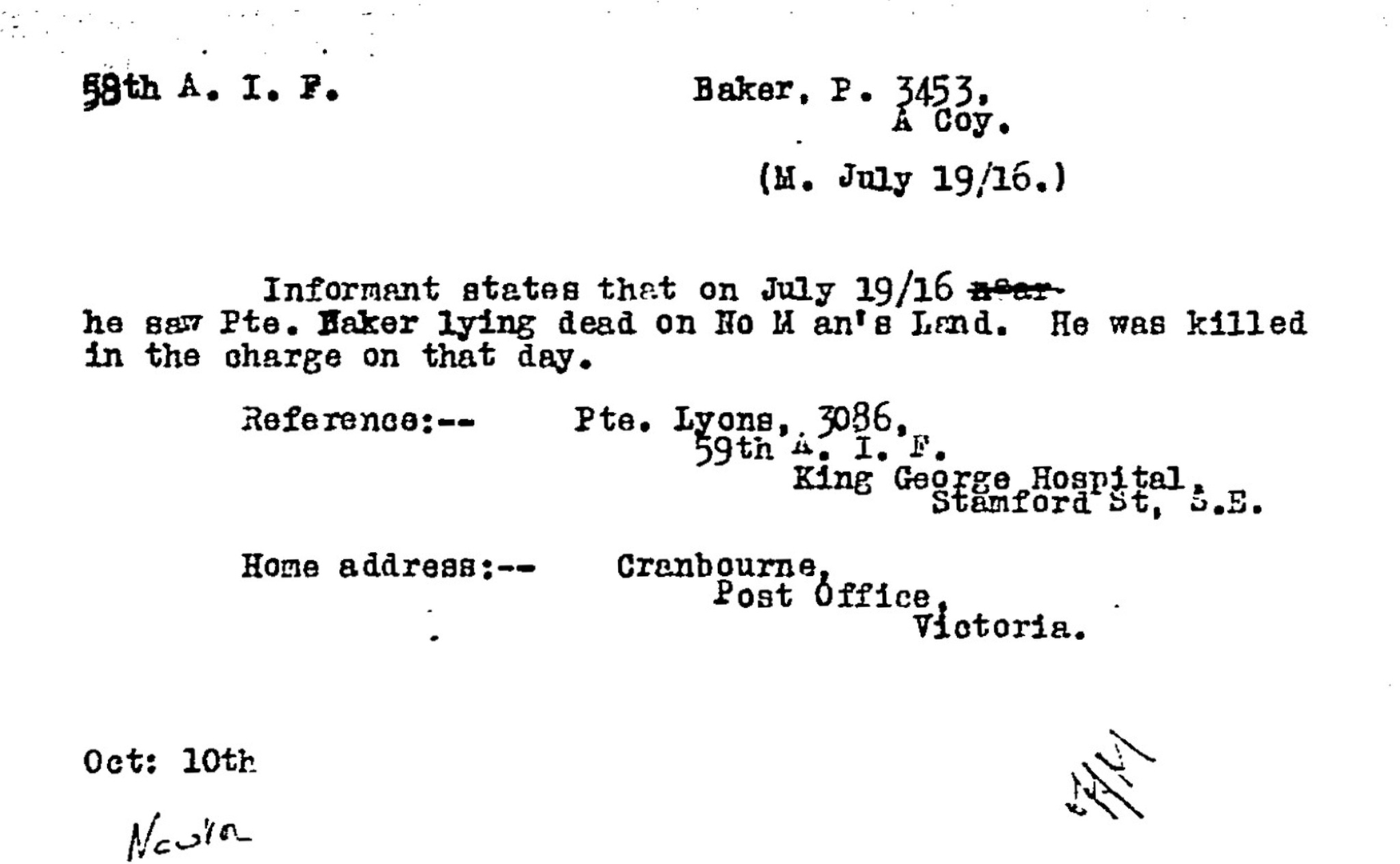

While the Army and the Red Cross efforts to identify the all the missing soldiers were underway, given the scale of the battle and all those in the Somme, it was a large task. A 10 October 1916 witness statement from Private William Egan Lyons (3086) file said that Percy had been killed during the charge and left in No Man’s Land.

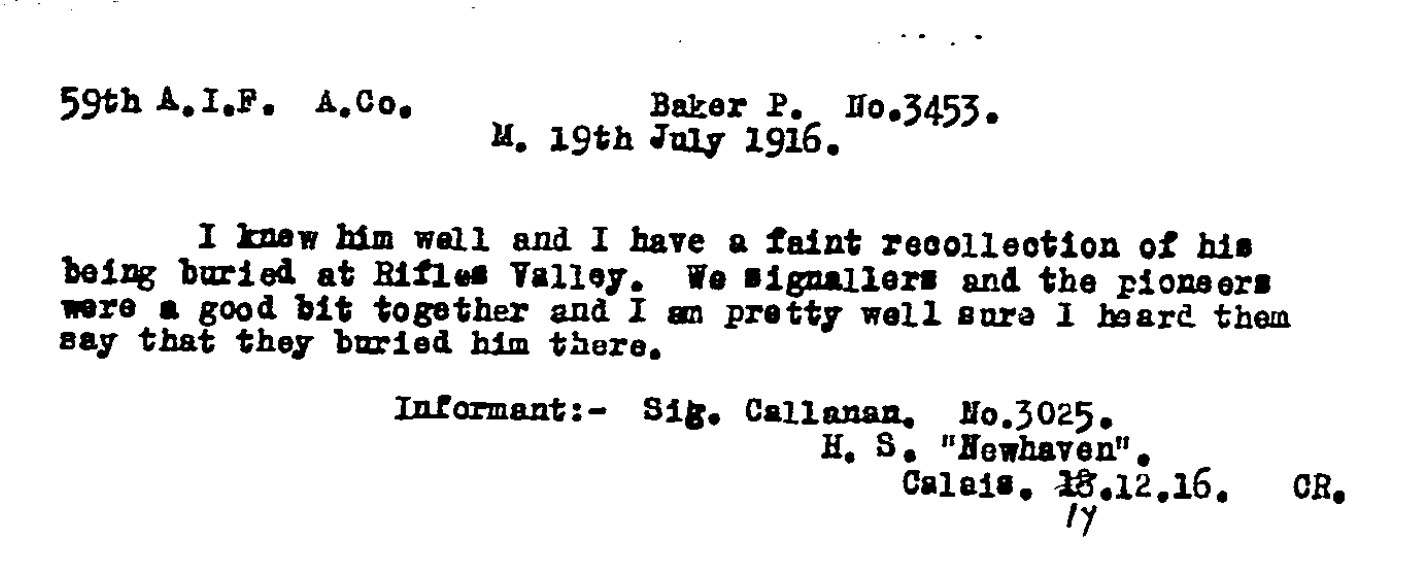

However, Signaller Callanan (3025), recalled in December 1916 that he had a faint recollection of Baker being buried at the Rifle Valley aid station, noting that the signallers and pioneers had been working together and that he was fairly sure he had heard they buried him there.

No other reports were found, but it wasn’t until a formal Court of Enquiry held in the field on 29 August 1917 finally determined that Percy had been killed in action on 19 July 1916. His body was never recovered. Percy was awarded the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll. He is memorialised at VC Corner Cemetery at Fromelles, the Australian War Memorial, the Terang War Memorial and the Terang 100th Centenary of Armistice honour board.

Hughie and Charlie

Hughie survived the fighting at Fromelles, but soon afterwards, 13 September 1916, while the 59th were still in the vicinity of the battle, he received a severe gunshot wound to the chest. He was evacuated through Boulogne and treated at the Norfolk War Hospital, Thorpe and at Harefield Hospital, where he was described as having “a penetrating foreign body still in thorax.” After over a year in hospitals, he was declared medically unfit and returned to Australia on 21 December 1917. He was discharged from the AIF in March 1918.

Though the war had left its mark, he built a life with Vera Linton Black, raising eight children and watching the generations grow. He named one of his own sons Percy, keeping alive the name of the brother he had lost on the Western Front. Hughie died at Castlemaine, Victoria on 21 December 1984, aged 89. Their mate Charlie Bannon was also killed during the assault. His battalion advanced through the same fire-swept zone and was virtually destroyed in front of the Sugarloaf. His body was recovered, however, and he was buried at Rue-du-Bois Military Cemetery, Fleurbaix, 20 July 1916, by Rev. F.P. Williams.

Finding Percy

Percy’s remains were not recovered; he has no known grave. After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including one of the 239 unidentified soldiers from the 59th Battalion. We welcome all branches of Percy’s family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification particularly those with roots in Colac or Terang, Victoria or Somerset, England.

If you know anything of family contacts, please contact the Fromelles Association. We hope that one day Percy will be named and honoured with a known grave. Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Percy’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Percy Baker (1893–1916) |

| Parents | Henry (Harry) Baker (1856–1933) and Mary Jane Menzies Spencer (1865–1901), Colac, Victoria |

| Siblings | Bertie Harold Baker (1890–1975) m Eileen Bourke | ||

| Hughie (Hugh) Baker (1895–1984) m Vera Linton Baker | |||

| Kezia Jane Baker (1896–1979) m Cyril Jennings | |||

| Mary Elizabeth Baker (1901–) | |||

| Paternal Half Siblings | Robert Henry Baker (1883–1909) | ||

| Charles Frank Baker (1884-1884) | |||

| Charles Baker (1886-1886) | |||

| Henry Ernest Baker (1887–1976 m Margaret Halliday) | |||

| Violet Baker (1905–1991) m Alfred Beck | |||

| Emily May Baker (1908–1992) m Robert Vanotto | |||

| Priscilla Baker (1909–1977) m Noel Walker | |||

| Walter Baker (1913–1914) died infancy |

| Maternal Half Siblings (through mother’s first marriage) | Catherine Emily (Minnie) Maud Lange (1885–1935) m Charles Baker | ||

| Walterena Ruth Lange (1886–1935) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | George Baker (1818–1906), Saunton Prior, Somerset and Elizabeth Thorogood (1830–1882), Duneed, Victoria | ||

| Maternal | James Spencer (1844–1918) England & Catherine Provan Menzies (1833–), Pleasant Creek, Victoria, born England |

Links to Official Records

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).