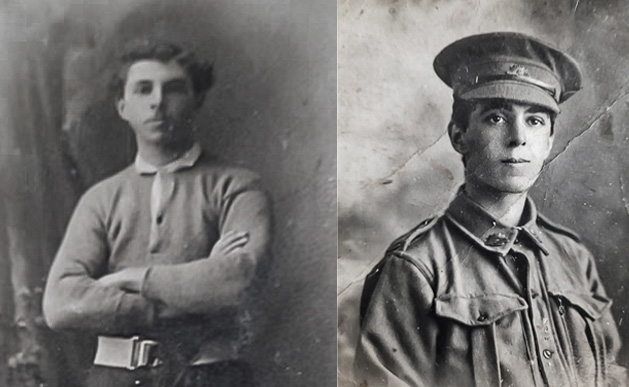

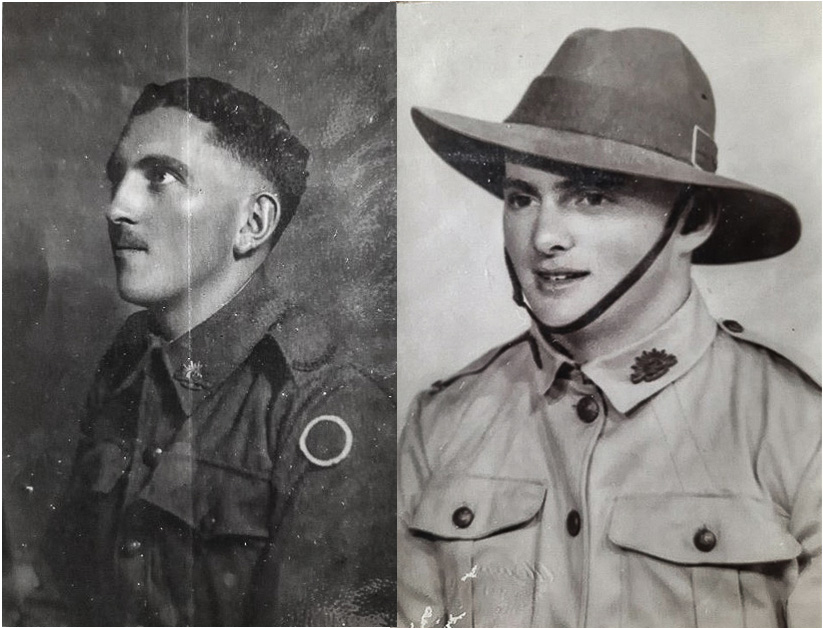

William Henry TURNER

Eyes brown, Hair dark brown, Complexion medium

A story of cousins, local lads, family, and war – William Henry Turner

We thank William’s family for their invaluable contribution in piecing together this story.

William Henry Turner was born 4 January 1893 in Picton, New South Wales where his parents, Henry Turner and Minnie Rose O’Keeffe, had been married the prior year. Henry and Minnie went on to have ten more children over the next twenty years, two of whom died in infancy. The Turner family were involved in the cedar felling industry in the

Jamberoo/Kiama area and later in Brooklet.

At the time of enlisting In October 1915, William Turner was a 22-year-old schoolteacher at Georgeville, near Tambar Springs, New South Wales, the town to where he returned on discharge. He enlisted in Gunnedah in the Narrabri district and was sent to camp in Sydney and allocated to the 18th Battalion.

While in camp it is likely that he met up with his 18-year-old cousin James Joseph Lee who had enlisted in June 1915 in his hometown of Merriwa. James was the son of Minnie’s sister, Annie Lee (nee O’Keeffe).

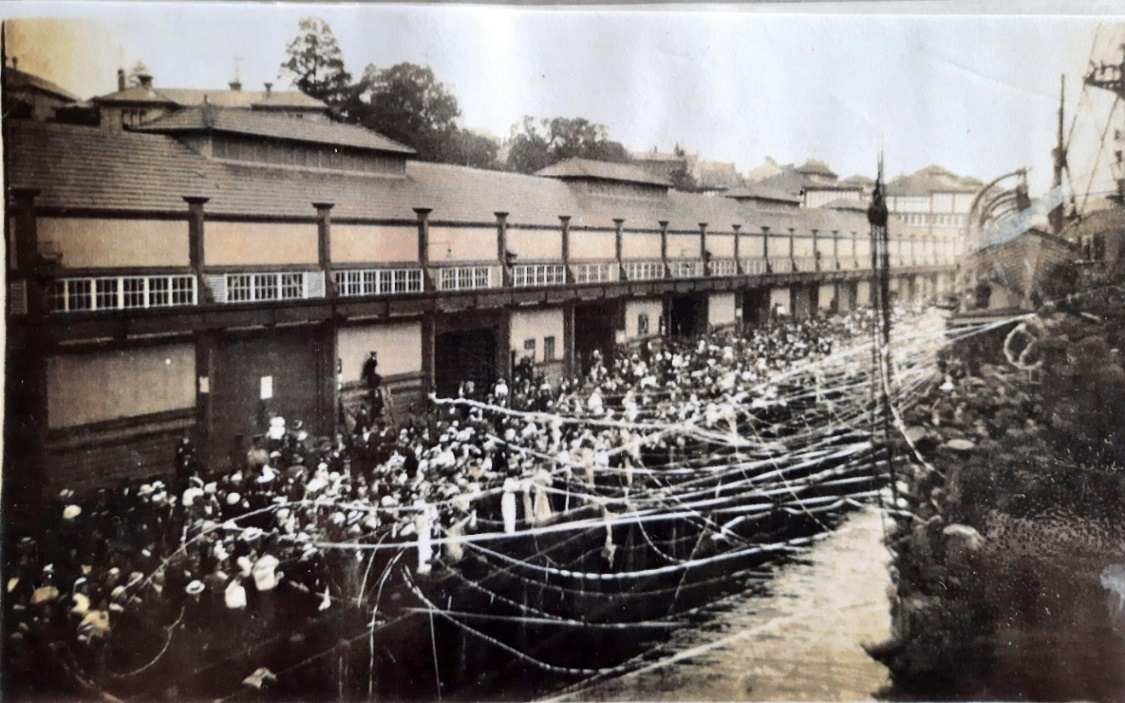

Despite being the first to enlist, James was destined to remain in Australia a few extra months before following his cousin William in embarking for Egypt. Private 3606 William H. Turner left Australia on HMAT A60 Aeneas on 20 December 1915 with the 18th Battalion while Private 4533 James J. Lee left Sydney two months later in February 1916. James was with the 13th Battalion on board HMAT A70 Ballarat arriving in Egypt in late March.

Also on board the troopship Aeneas with William in the 18th Battalion were at least eight other young men from the little town of Tambar Springs. This group of nine included three with the surname Turner – “our” William as well as two brothers, Frederick John and another William. This other William Turner (3607) had the next consecutive service number to our William Henry Turner (3606). What are the chances of confusion arising with two Private William Turners from Tambar Springs on the same ship, same battalion with near identical service numbers? No specific instances of mix-ups are documented in the two soldiers’ files but it was a likely outcome in day to day interactions. The other William (3607) was repatriated back to Australia in early 1916 for medical reasons so this reduced the risk of confusion. Researchers have not spotted any family connection between the two Turner families, but it is possible there is an earlier generational connection.

Transfer to the 54th

After arrival in Egypt, William as part of the 18th Battalion continued with training and military exercises as the authorities began the massive task of re-organising the AIF post-Gallipoli. As a part of that strategy, the 54th Battalion was raised to combine fresh reinforcements with seasoned Gallipoli veterans. The new battalion became part of the 14th Brigade of the 5th Australian Division.

From the group of nine Tambar Springs lads in the 18th, only two were transferred to the 54th in early April 1916– boundary rider, William Daley (3636) and our schoolteacher, William Henry Turner (3606). William Daley’s story is also told on this website – see William DALEY

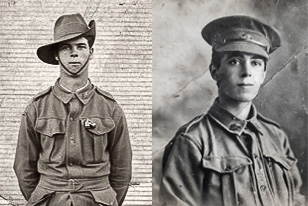

But, there was another familiar addition – our William’s young cousin, baker and farm labourer, James J. Lee (4533), from the 13th Battalion. James was also transferred to the 54th at this time. Coincidentally, James also had a namesake transferred into the 54th that same month – James Lee (4822) – also around 20 years of age and from the Hunter Valley. Another opportunity for confusion and, sadly, confusion did arise. The stories for both James Joseph Lee 4533 and James Lee 4822 are included on this website.

Moving to France in June 1916, the 54th fought its first major battle on the Western Front at Fromelles on 19 July. It was a disaster. The 54th was part of the initial assault and suffered casualties equivalent to 65 per cent of its fighting strength.

Missing in action

On about 8 August 1916, just over a fortnight after the Battle of Fromelles, Henry and Minnie Turner received a cable advising that their son, William, was missing in action since 19-20 July. At much the same time, Minnie’s sister, Annie Lee, received a cable advising that her son, James J. Lee, had been killed in action between 19 and 20 July 1916. The Turner family must have feared the worst – that William had died with his young cousin in that same battle.

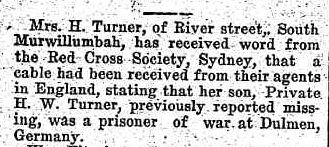

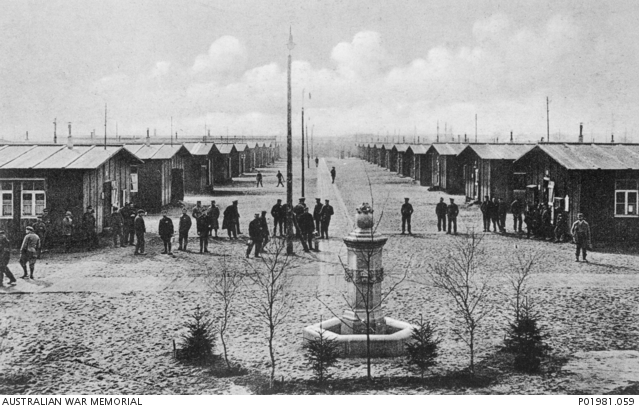

Some six weeks later, the Turner family received the welcome news that Private William Henry Turner, 54th Battalion, was a prisoner of war and being held in Dulmen Prison Camp in Germany. At least he was alive.

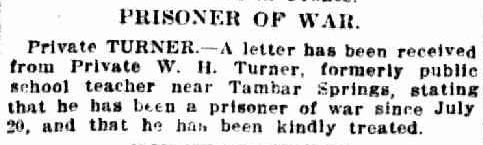

Knowing he was alive must have been a relief but the family would have been desperate to know if he was wounded and if he was being treated well. Communication options were very limited with long delays and letters to and from prisoners closely monitored and censored. It was a long wait until late November before they received word from William himself that he was being “kindly treated”.

Prisoner of War

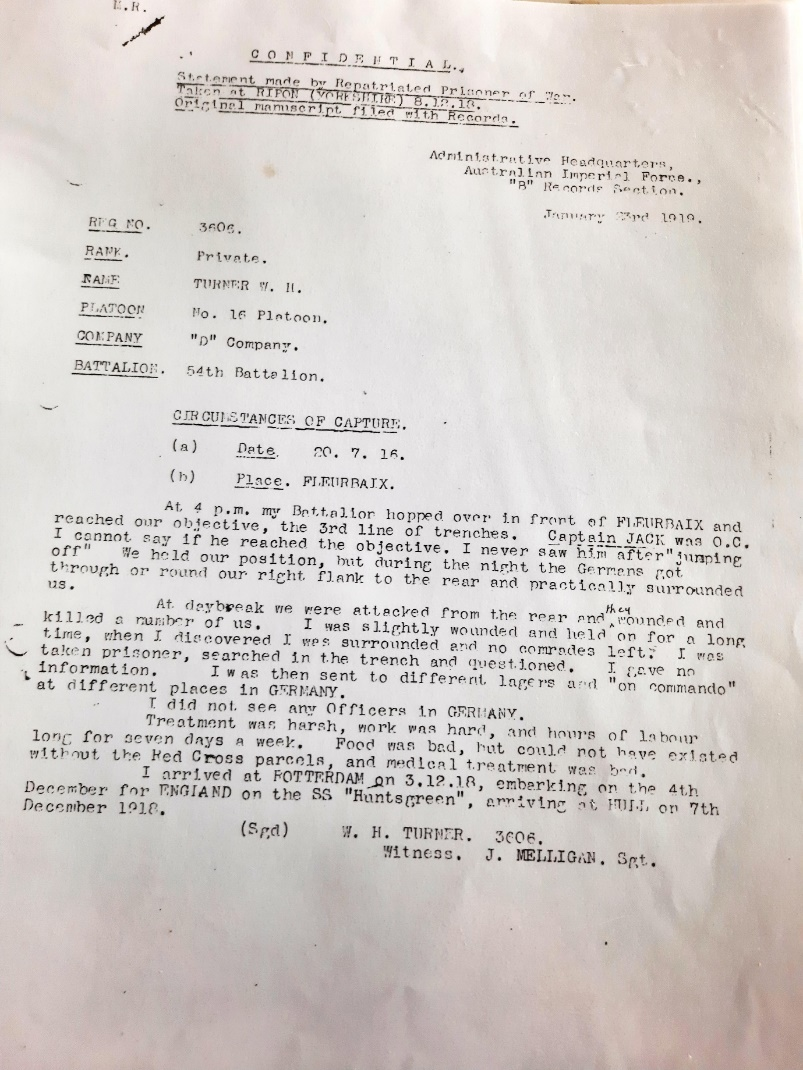

William was held as a prisoner in Germany for the duration of the war. In a statement made after his release, William described his capture as follows:

“At 4 p.m., my Battalion hopped over in front of Fleurbaix and reached our objective, the 3rd line of trenches. Captain Jack was O.C. I cannot say if he reached the objective. I never saw him after “jumping off.” We held our position, but during the night the Germans got through or round our right flank to the rear and practically surrounded us.

At Daybreak we were attacked from the rear and they wounded and killed a number of us. I was slightly wounded and held on for a long time, when I discovered I was surrounded and no comrades left. I was taken prisoner, searched in the trench and questioned. I gave no information.”

According to historian Aaron Pegram in his 2008 article “Australia’s Fromelles prisoners” :

The Fromelles prisoners constituted the second largest group of Australians to be captured in a single engagement. In part, they were too successful in gaining ground, but sufficient support was not planned nor could be made available. Having survived the devastating machine-gun fire sweeping no man’s land, groups along the 8th and 14th Brigade fronts succeeded in breaking through the German front line.

Against a background of overwhelming odds, and superior tactical positions held by the Germans, and very much to the chagrin of those still willing and able to fight, the order to surrender was passed along the 14th Brigade front. A white flag produced by an Australian officer sapped whatever morale remained. When the Germans recaptured the front line, those attempting to withdraw were also taken prisoner.

After capture, officers were separated from their men. The Fromelles prisoners were gradually distributed across Germany, where they were imprisoned in camps alongside British, French and Russian troops. The treatment of prisoners varied greatly, but they generally fared better the further away from the front line they were moved.

William described his two and a half years in Germany as follows:

“Treatment was harsh, work was hard, and hours of labour long for seven days a week. Food was bad, but could not have existed without the Red Cross parcels, and medical treatment was bad.

This is quite different to his letter home to his family back in 1916 when he spoke of being kindly treated. That letter was most likely a diplomatic and highly censored message to placate his parents’ fears and also to avoid earning the ire of his captors.

In a local newspaper, William reported that he spent time in Russia as well as numerous German camps and told the story of a close call with his German captors:

“He was transferred to various camps, and was for some time in Russia. He was at one time sentenced to be shot for resenting treatment that was being meted out to him in a mine, and he claims that it was only through the intervention of an officer, whom he thought to be an Englishman, that his life was saved. For the offence he was ordered to undergo twenty-one days of bread and water, at the expiration of which time he was to be ‘stood up against the wall’; but within a day of completing the term of his sentence he was reprieved.”

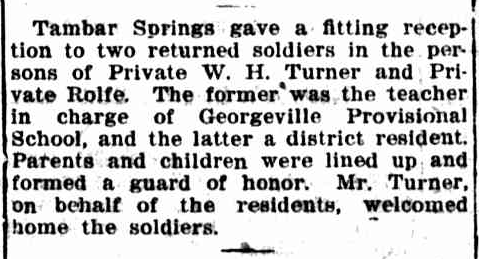

William was released from the prison camp and repatriated to England in December 1918. He boarded the Nevassa in March 1919 to return home and arrived on 19 April. He was welcomed home by his local community in Tambar Springs in early June and discharged 20 June 1919.

Those from Tambar Springs with William

Of the group of nine identified from Tambar Springs who embarked on board HMAT Aeneas with William H. Turner, only four returned home to Australia. Four lie in unknown graves and the fifth is buried in the Bellicourt British Cemetery.

Those killed in action:

- Pte 3636 William DALEY killed at Fromelles 19-20 July 1916 – no known grave

- Cpl 3643 Royal A. GRACE killed in France 8 November 1916 – no known grave

- Pte 3686 Frederick J. WATT killed in France 3 May 1917 – no known grave

- Pte 3617 Walter WALLACE killed in France 3 May 1917 – no known grave

- Cpl 3634 Robert COCK, DCM killed in France 3 October 1918 – buried Bellicourt British Cemetery, France

Those who returned home to Australia:

- Pte 3607 William TURNER – illness, returned to Australia 11 April 1916

- Pte 3644 Harold GRACE, MM – wounded, returned to Australia 15 February 1918

- Pte 3606 William H. TURNER – prisoner of war, returned to Australia 5 March 1919

- Pte 3680 Frederick J. TURNER, MM – returned to Australia 26 July 1919

Tambar Springs is reputed to have had the largest number of men per capita enlisted in the army in the Commonwealth, over both world wars. This small New South Wales town also lays claim to having the earliest memorial to World War I servicemen in Australia. The memorial was erected in December 1918 consisting of an Italian marble obelisk topped by a sculpture of a young soldier. It listed in order of the date of enlistment the names of all district residents who volunteered, noting those killed in action (14 in total).

After the war

Eighteen months after arriving home, William married local Tambar Springs girl, Peg (Mary Margaret Anne) George, in October 1920. William and Peg had one daughter and six sons with George and Victor, the two eldest, serving in the AIF in WW2.

After the war, William returned to teaching serving in small country schools in New South Wales including the Opossum Creek public school, near Byron Bay where he taught from 1925. In 1929 he moved to Tamworth and took up droving – perhaps with his father-in-law, George George, who was by then a Tamworth-based drover.

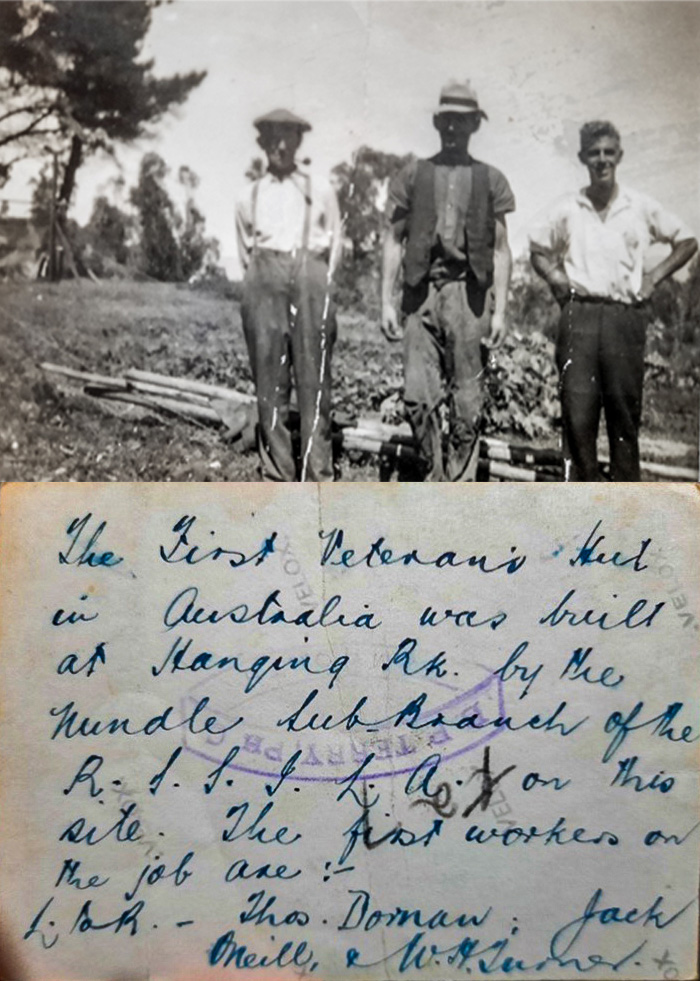

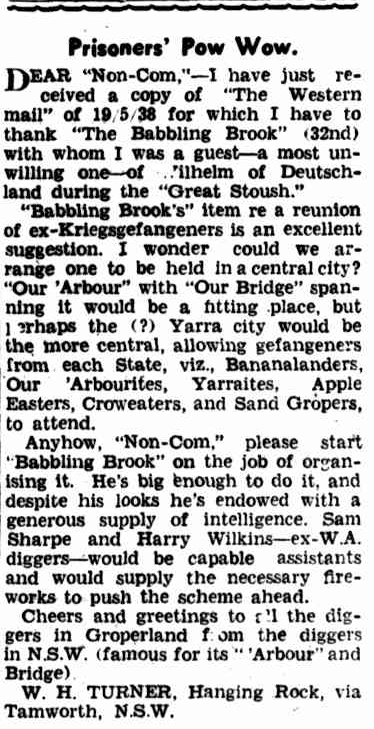

However, by 1934, William had returned to his earlier profession and was teaching at Hanging Rock, an old gold-digging town near Tamworth. It seems that William kept contact with his ex-servicemen comrades. There is a photo showing his involvement in building what is described as the first Veterans’ Hut in Australia at Hanging Rock and, there are also letters showing William’s support for an ex-PoW reunion.

The photo and the description above are both portrayed on an historical marker at what is now the fire station, Barry Road, Hanging Rock – see image. There is also a 1937 news report.

“The Nundle sub-branch of the RSL has erected the first war veterans' home in this part of the State, at the Hanging Rock Settlement. An area of land was obtained, and the hut was built to accommodate two men. The land can be cultivated.”

From electoral rolls, William was teaching at Bribbaree, west of Young, in 1943 but by 1949 he was a labourer in Gunnedah and later a storeman in Port Macquarie and in Canley Vale.

He died aged 81 on 15 December 1974 and is buried with his wife Peg (1896-1977) at the Eastern Suburbs Memorial Park in Randwick, dearly beloved and sadly missed.

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).