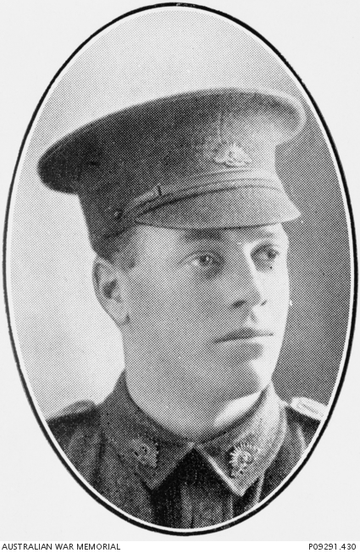

Bertie BEARE

Eyes grey, Hair fair, Complexion fair

Bertie Beare - "I'll have just have one more shot"

Can you help us identify Bertie?

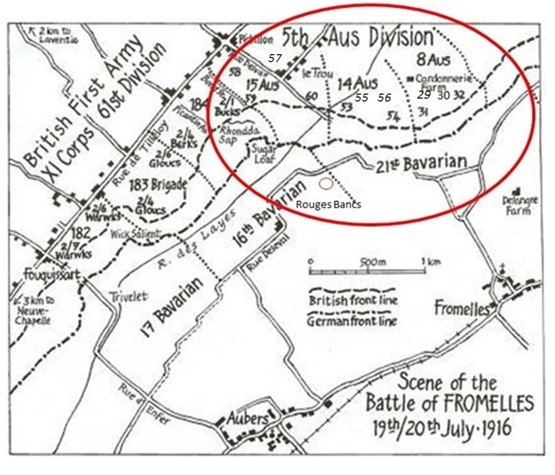

Bertie was killed in Action at Fromelles, but his body has never been identified. As part of the 32nd Battalion he was positioned near where the Germans collected soldiers who were later buried at Pheasant Wood. There is a chance he might be identified, but we need help.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification.

If you know anything of contacts for Bertie, please contact the Fromelles Association.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

Early Life

Albert “Bertie” Beare was born 22 December 1894 in Moonta Mines, South Australia, the second child of Nicholas and Emily Beare (nee Martin). He had two brothers and two sisters:

- Beatrice (1892–1901)

- William Henry (1905–1959) married Irene Walters

- Beatrice Lola (1908–1998) married Arthur George Blackburn

- Percival "Percy" (1912–1975). married Mabel Jean Eliza Shore

Like many people of this copper mining area, Emily’s family came from Cornwall, Pelean-in- Perran, in 1851. Nicholas Beare came from Redruth, Cornwall. He left from Plymouth on the Lochee, November 1876, arriving in 1877 as a 7 year old with his mother Catherine and five siblings. There were already Beare families in Moonta at this time. Nicholas and Emily Martin married at Moonta in 1892.

Bertie grew up in Wallaroo Mines, attending Wallaroo Mines Public and High Schools.

On leaving school, Bertie worked as a grocer’s assistant at local Kadina stores, Beckwith and Dowling, W.B. Noell and Bond Brothers. He was described being somewhat of a quiet nature, but always obliging and held in high esteem by his workmates and friends.

Source: Kadina and Wallaroo Times (SA : 1888 - 1954), Saturday 15 September 1917, page 2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article109182426

According to his mother, Bertie was "enthusiastic in military matters’ from boyhood". Before enlistment he served for 1 year in the 81st Bn Senior Cadets, and then 3 years in the 81st Infantry, Citizen Military Forces.

Off to War

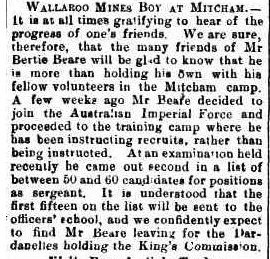

Bertie enlisted on 15 June 1915 and he began his military training at the Mitcham Camp. After initially being assigned to the 10th Reinforcements of 10th Battalion, he was transferred to A Company of the 32nd Battalion when it was raised at Mitcham in August. Two weeks later, at the beginning of September, he was promoted to Sergeant, having successfully completed the Sergeants’ course at Mitcham.

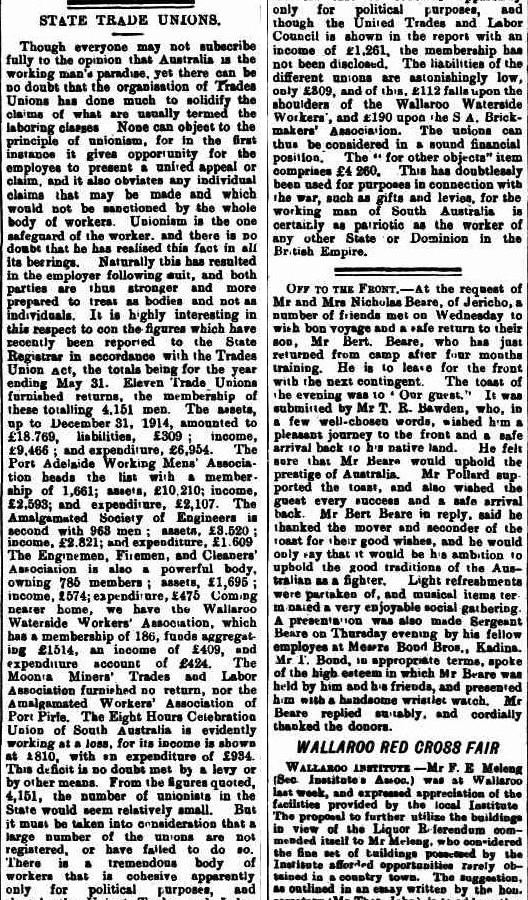

Bertie was farewelled in Kadina by family and friends on 20 October where he responded to their best wishes by saying that it was his “ambition to uphold the good traditions of the Australians as a fighter”.

Bertie left Adelaide with the 32nd Battalion on HMAT A2 Geelong on 18 November 1915.

As reported in The Adelaide Register:

“The 32nd Battalion went away with the determination to uphold the newborn prestige of Australian troops, and they were accorded a farewell which reflected the assurance of South Australians that that resolve would be realized.”

Bertie arrived in Suez on 14 December 1915 and moved to El Ferdan just before Christmas. A month later the 32nd marched to Ismailia and then to the major camp at Tel-el-Kebir where they stayed for February and most of March. Tel-el-Kebir was about 110 km northeast of Cairo and the 40,000 men in the camp were comprised of Gallipoli veterans and the thousands of reinforcements arriving regularly from Australia.

Their next stop was at Duntroon Plateau and then at Ferry Post until the end of May where they trained and guarded the Suez Canal. Their last posting in Egypt was a few weeks at Moascar. One soldier’s diary complained of being “sick up to the neck of heat and flies”, of the scarcity of water during their long marches through the sand and he described some of the food as “dog biscuits and bully beef”. He did go on to mention good times as well with swims, mail from home, visiting the local sights and the like.

Source: AWM C2081789 Diary of Theodor Milton PFLAUM 1915-16, page 29, page 12

During their time in Egypt the 32nd had the honour of being inspected by H.R.H. Prince of Wales.

After spending six months in Egypt, the call to support the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front came in mid-June. The 32nd left from Alexandria on the ship Transylvania on 17 June 1916, arriving at Marseilles, France on 23 June 1916 and they then immediately entrained for a three-day train trip to Steenbecque. Their route took them to a station just out of Paris, within sight of the Eiffel Tower, through Boulogne and Calais, with a view of the English Channel, before disembarking and marching to their camp at Morbecque, about 30 kilometres from Fleurbaix.

Theodor Pflaum (No. 327) and Wesley Choat (No. 68) wrote about the trip:

“The people flocked out all along the line and cheered us as though we had the Kaiser as prisoner on board!!” – Theodore Pflaum

“The change of scenery in La Belle France was like healing ointment to our sunbaked faces and dust filled eyes. It seemed a veritable paradise, and it was hard to realise that in this land of seeming peace and picturesque beauty, one of the most fearful wars of all time was raging in the ruthless and devastating manner of "Hun" frightfulness”. – Wesley Choat

They were headed to the area of Fleurbaix in northern France which was known as the ‘Nursery Sector’ – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times did not last long. Training continued with a focus on bayonets and the use of gas masks, assuredly with a greater emphasis, given their position near the front. The 32nd moved to the Front on 14 July and Bertie was into the trenches for the first time on 16 July, only three weeks after arriving in France.

The Battle of Fromelles

On the 17th they were reconnoitering the trenches and cutting passages through the barbed wire, preparing for an attack, but it was delayed due to the weather. D Company’s Lieutenant Sam Mills’ letters home were optimistic for the coming battle:

“We are not doing much work now, just enough to keep us fit—mostly route marching and helmet drill. We have our gas helmets and steel helmets, so we are prepared for anything. They are both very good, so a man is pretty safe.”

The overall plan was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The 32nd Battalion’s position was on the extreme left flank, with only 100 metres of No Man’s Land to get the German trenches. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 31st Battalion on their right. However, their position made the job more difficult, as not only did they have to protect themselves while advancing, but they also had to block off the Germans on their left, to stop them from coming around behind them.

On the morning of the 18th, Bertie’s A Company and C Company went into the trenches to relieve B and D Companies, who rejoined the next day. The Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. Bertie’s parents were told that just before the Battalion launched its attack at Fromelles, he was wounded in the shoulder by shrapnel.

He was urged by his comrades to go to the dressing station for medical attention. However, he refused, stating that after waiting for so long for the vital moment he intended to lead his company over the parapet. The charge over the parapet began at 5.53 PM. Bertie’s A Company and C Company were the first and second waves to go, B & D were in the third and fourth.

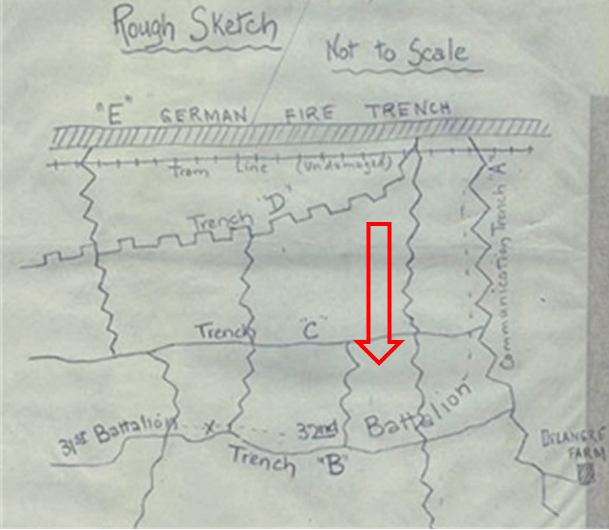

They were successful in the initial assaults and by 6.30 PM were in control of the German’s 1st line system (map Trench B), which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

Unfortunately, with the success of their attack, ‘friendly’ artillery fire caused a large number of casualties because the artillery observers were unable to confirm the position of the Australian gains. They were able to take out a German machine gun in their early advances, but were being “seriously enfiladed” from their left flank.

By 8.30 PM their left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and the 32nd were told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine gun fire from behind them from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. In the early morning of the 20th, the Germans began a counterattack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map).

Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to regain that trench and envelop the men of the 32nd. At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance they could offer was with rifles:

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

What was left of the 32nd had finally withdrawn by 7.30 AM on the 20th. The initial roll call count was devastating – 71 killed, 375 wounded and 219 missing, including George. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield.

The final impact was that 228 soldiers of the 32nd Battalion were killed or died from wounds sustained at the battle and, of this, 166 were unidentified. Lieutenant Sam Mills survived the battle. In his letters home, he recalls the bravery of the men:

“They came over the parapet like racehorses……… However, a man could ask nothing better, if he had to go, than to go in a charge like that, and they certainly did their job like heroes."

What Happened to Bertie?

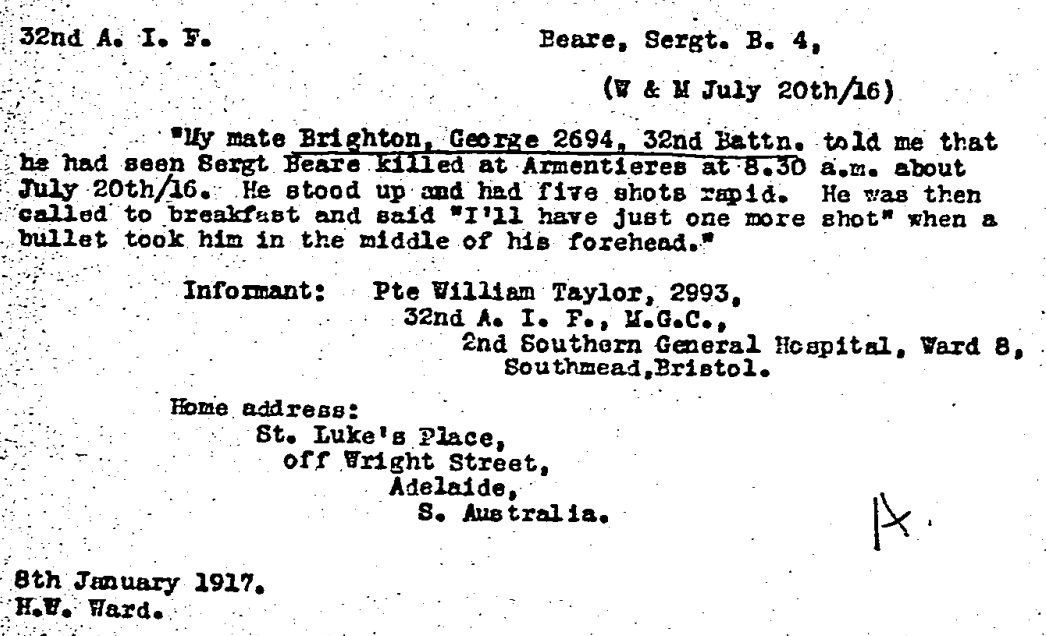

Bertie was among the missing after the battle, but it is unclear what happened to Bertie during the battle. The only witness statement is from the Red Cross Missing and Wounded files and it is a VERY curious description (but is also very precise given it was six months later) of Bertie’s possible fate – killed by sniper fire while in the Australian lines AFTER the battle.

The Army sent this to the family, but they also cited:

“We must emphasize the purely unofficial character of this report and we cannot answer for its reliability.”

While this is not impossible, if this had been the case, Bertie surely would have had a proper burial. He remains missing to this day.

The Family’s Anguish Over Not Knowing

Bertie’s parents were not informed until 30 August (six weeks after the battle) that their son was ‘missing’. His name was in the 207th Casualty list printed in newspapers on 7 September. The family then had to live with the dreadful suspense of not knowing anything for certain. They made every effort to get information. Emily Beare later wrote that ‘We sent straight to different places through the Red Cross’. On 5 September, Bertie’s father Nicholas wrote to the Red Cross Information Bureau in Adelaide asking for their assistance in tracing Bertie.

In October, his mother wrote directly to the Red Cross Headquarters in London, and in October a friend of the family made a personal enquiry at the Red Cross Information Bureau in Adelaide on behalf of Emily. In an October letter to the Red Cross headquarters in Sydney, Emily’s desperation, and fear for the worst is obvious. She knew that some parents of those who had been taken prisoner had received cards from their sons. She wrote of the “terrible suspense” of “not knowing what to think about him”. Her PS was a plea - ”If you should know where our dear boy is would it be too much to ask you to write to him and let him know that we are all well and thinking of him.”

But Emily lamented later, the family “could get no tidings through them”. Bertie’s ‘young lady’, Hilda Jackson of Kadina, wrote directly to the 32nd Battalion seeking information. She received a reply that it was not able to give any further information.

(Note – There also was a Red Cross witness statement, taken in December 1916 that Bertie had written a letter to one of the Sergeants about being wounded and in hospital in England. There is no mention of this communication being passed on to the family.) In September 1917, the family was informed that following a Court of Enquiry, their son was officially pronounced Killed in Action. Immediately, and on the anniversary of his death in following years, his parents, and his ‘loving’ and ‘sincere’ friend Hilda Jackson, put joint and separate notices in the ‘Heroes of the Great War’ columns of city and local newspapers.

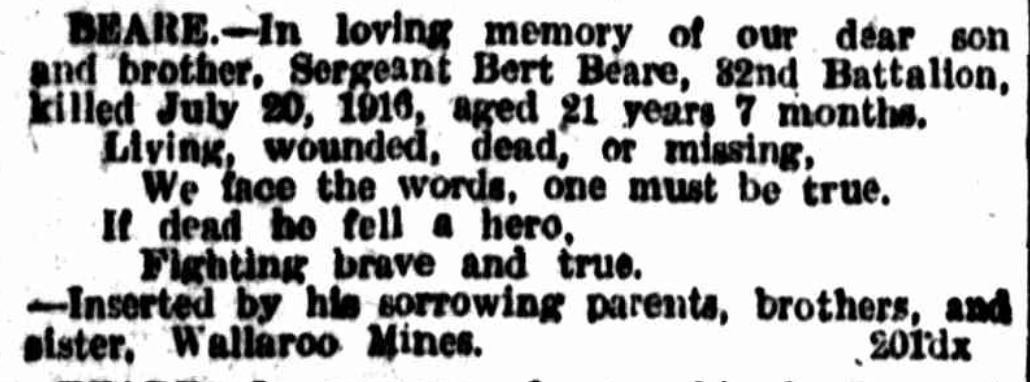

The verse used in their 1918 memorial captures the anxiety, uncertainty and grief of Bertie’s parents, and the effects that words such as ‘missing’ and ‘dead’ had on the family – and the lingering hope that things might be different:

Living, wounded, dead or missing

We face the words, one must be true

If dead he fell a hero

Fighting brave and true

Nicholas and Emily Beare never found or received any further information about the fate of their son. In 1921, Mrs Beare wrote, in response to a circular letter from the Military seeking any information which might help discovery of their son’s body, ‘I should be grateful to you if you could get any tidings that our dear son’s body has been found and identified , as it would be a great consolation to us to know something about it.’

Source: NAA File

Bertie Beare is commemorated at:

- V.C. Corner (Panel No 4), Australian Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles, France.

- Adelaide National War Memorial

- Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour,

- Kadina & District WW1 Roll of Honor,

- Kadina Memorial High School WW1 Honour Roll,

- Kadina Town Hall WW1 & WW2 Roll of Honour,

- Kadina War Memorial Arch,

He posthumously received the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal, and the Victory Medal.

Finding Bertie

After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including 41 of the 166 unidentified soldiers from the 32nd Battalion.

We welcome all branches of Bertie’s family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification. If you know anything of family contacts, please contact the Fromelles Association. We hope that one day Bertie will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Bertie’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Albert Beare (1894-1916) |

| Parents | Nicholas Beare (1870–1944), born Redruth, Cornwall; died Adelaide, SA. Emily Martin (1872–1952), born Moonta, SA; died Moonta, SA |

| Siblings | Beatrice (1892-1901) | ||

| Wiliam Henry (1905-1959) married Irene Walters | |||

| Beatrice Lola (1908-1998) married Arthur George Blackburn | |||

| Percival “Percy” (1912-1975) married Mabel Jean Eliza Shore |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | William Henry Beare (1833–1893) and Catherine Spragg Nicholls (1834-1891) Gwennap Cornwall | ||

| Maternal | Michael Martin (1828-1907) Jane Martin (1828-1896) both from Cornwall |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).