Herbert John BURBIDGE

Eyes hair dark, Hair complexion dark, Complexion scars both forelegs

Herbert, Maurice and Eric Burbidge – Three Brothers Lost to War

Can you help us identify Bert?

Herbert “Bert” Burbidge was killed in Action at Fromelles, but his body has not been found.

In 2008, a mass grave was discovered at Pheasant Wood, containing the remains of 250 Australian and British soldiers recovered by the Germans after the battle. Since then, DNA has been used to identify many of the fallen.

There is a chance he might be identified, but we need help. We are searching for suitable family DNA donors.

If you know anything of contacts for Bert here in Australia, England, or Singapore, please contact the Fromelles Association.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

Early Life

Herbert John Charles Burbidge, known as Bert, was born on 13 May 1887 in Singapore, then part of the Straits Settlements under British colonial rule. He was the eldest child of William Mark Burbidge, an engineer, and Eva Julia Forrest (1868–1939), who later trained as a nurse. The children of William and Eva were:

- Herbert (Bert) – born 1887 in Singapore; served with the 32nd Battalion and was killed in action at Fromelles in 1916.

- Maurice Norman Henry – born 1891; served with the 32nd Battalion and died in 1919 during the influenza epidemic while on active service.

- Eric Malcolm – born 1892; served with the Durham Light Infantry and was killed in action in France in 1918.

- Helen Hope – born 1897, died 1986; married Sidney Allan.

In later years, two half-siblings were born in India after their father’s remarriage:

- Daphne Lillian Burbidge – born 1919 in India

- Addison Mark Burbidge – born 1925, died 1931

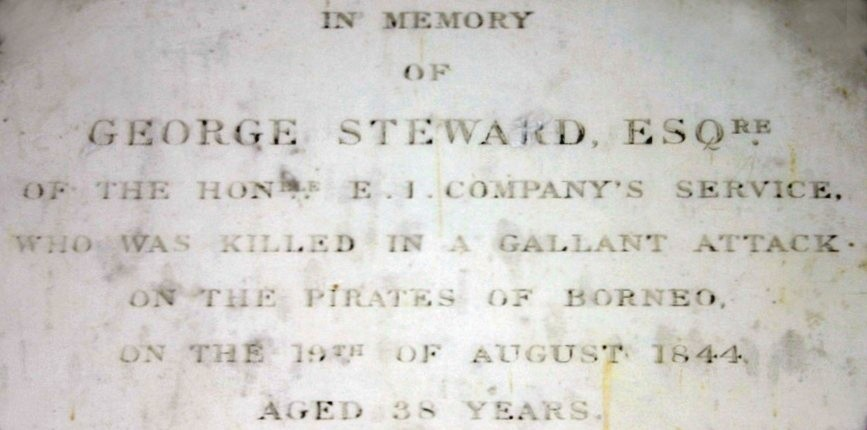

The Burbidge family was well-educated and mobile, their lives following the movements of the British Empire across Asia. Although all the older children were born in Singapore, they were raised within an environment that maintained strong connections to both India and England. The extended family had some notable historical connections. Herbert’s maternal grandmother, Julia Steward, was the daughter of George Steward, a British civil servant killed by pirates in Borneo in 1844 — an event recorded in British colonial history and memorialised in the UK. Read more here.

It is quite a read, featuring the East India Company, missionaries, rajahs, and pirates, even inspiring part of George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman adventure stories. This lineage clarifies that Bert was a descendant of both English and Malaysian families.

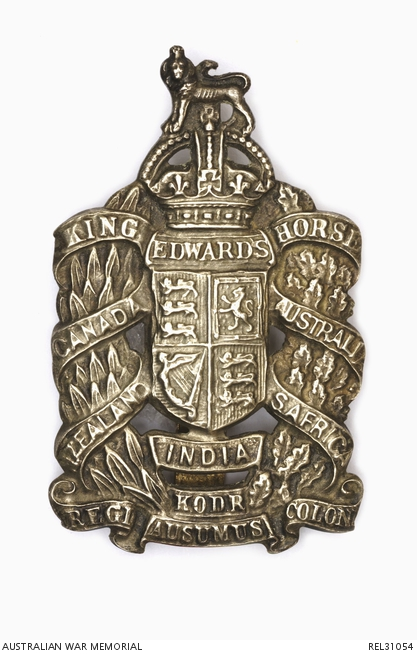

King Edward’s Horse, Chelsea

At some stage prior to emigrating to Australia, Bert served for four years with the King Edward’s Horse (The King’s Overseas Dominions Regiment), a cavalry regiment within the British Territorial Force based in Chelsea, London. This service provided him with significant military training and leadership experience.

Migration to Australia and Early Career

In the 1911 UK Census, Bert was recorded as a boarder in North Croydon, working as a secretary’s clerk for Dr Barnardo’s Homes. In October that year, his brother Maurice arrived in Port Adelaide on aboard the Otway. Bert is not listed with Maurice on the ship’s manifest, but they were rarely far apart. The two brothers settled in South Australia, while their parents and younger siblings remained in England.

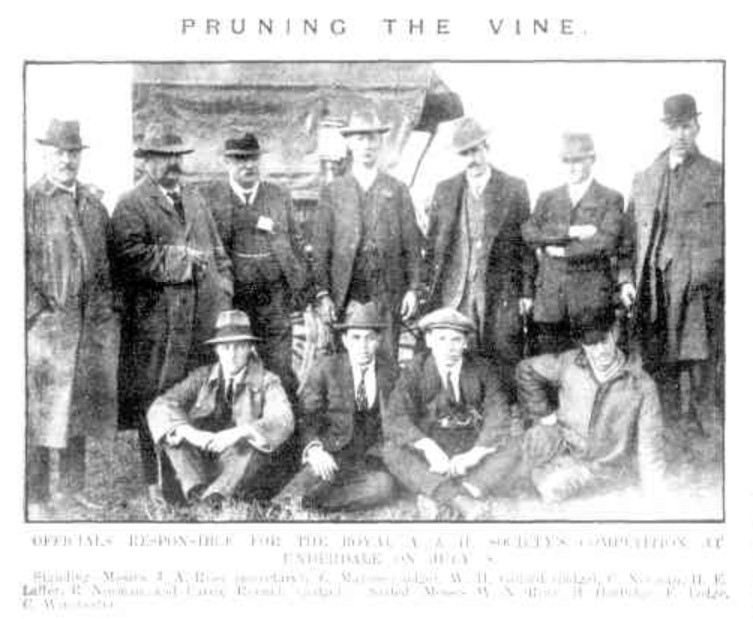

Their mother Eva worked as a nurse at St Luke’s Hospital in Chelsea and their father later moved to India. Bert settled in the coastal suburb of Semaphore, Adelaide, and worked as a clerk for the Chamber of Commerce in Exeter, South Australia. He was engaged in the local community, as seen in the 1914 article on the Royal Agricultural and Horticulture Society.

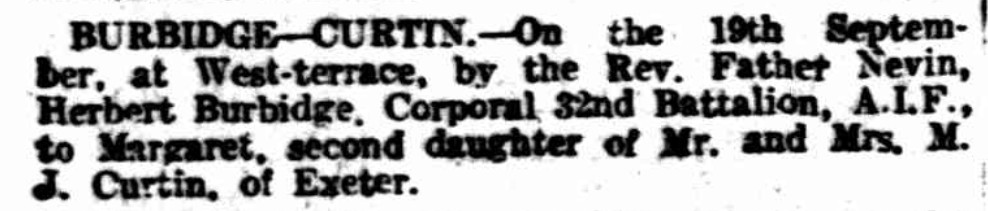

In September 1915 Bert married Margaret Agatha Curtin, daughter of Senior Constable John Curtin of Port Adelaide. Less than two months later, he enlisted in the AIF. Their daughter, Monica Ellen Burbidge, was born in May 1916, only two months before Bert was killed at Fromelles. Margaret never remarried.

Off to War

The 32nd Battalion was formed at Mitcham, South Australia on 9 August 1915. A and B Companies were to be from South Australia while C and D from Western Australia. There was much fanfare about this in South Australia, with gatherings, community support, such as the Cheer-up Society and reviews of the troops by the Premier. Bert was the first brother to enlist, 12 July 1915, and Maurice followed on 21 July 1915. They were both assigned to the 32nd Battalion.

As reported in The Adelaide Register:

“The 32nd Battalion went away with the determination to uphold the newborn prestige of Australian troops, and they were accorded a farewell which reflected the assurance of South Australians that that resolve would be realized.”

Egypt

The 32nd arrived in Suez on 14 December 1915 and moved to El Ferdan just before Christmas. A month later they marched to Ismailia and then to the major camp at Tel-el-Kebir where they stayed for February and most of March. Tel-el-Kebir was about 110 km northeast of Cairo and the 40,000 men in the camp were comprised of Gallipoli veterans and the thousands of reinforcements arriving regularly from Australia. Their next stop was at Duntroon Plateau and then at Ferry Post until the end of May where they trained and guarded the Suez Canal.

Their last posting in Egypt was a few weeks at Moascar. One soldier’s diary complained of being “sick up to the neck of heat and flies”, of the scarcity of water during their long marches through the sand and he described some of the food as “dog biscuits and bully beef”. He did go on to mention good times as well with swims, mail from home, visiting the local sights and the like.

Source: AWM C2081789 Diary of Theodor Milton PFLAUM 1915-16

During their time in Egypt the 32nd had the honour of being inspected by H.R.H. Prince of Wales.

To the Western Front

After spending six months in Egypt, the call to support the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front came in mid-June. They left from Alexandria on the ship Transylvania on 17th June 1916 and arrived at Marseilles, France on 23rd June 1916. After arriving in Marseilles, the 32nd departed by train for the two-day trip to Steenbecque and a march to Hazebrouck, about 30 kilometres from Fleurbaix. Their route took them to a station just out of Paris, within sight of the Eiffel Tower, then through Bologne and Calais, with a view of the Channel, and finally headed to St Omer and Hazebrouck. Theodor Pflaum (No. 327) wrote about the trip in his diary:

“The people flocked out all along the line and cheered us as though we had the Kaiser as prisoner on board!!”

Wesley Choat (No. 68), for one, was glad to be out of Egypt, but he was well aware of what laid ahead:

“The change of scenery in La Belle France was like healing ointment to our sunbaked faces and dust filled eyes. It seemed a veritable paradise, and it was hard to realise that in this land of seeming peace and picturesque beauty, one of the most fearful wars of all time was raging in the ruthless and devastating manner of "Hun" frightfulness”.

Training continued with a focus on bayonets and the use of gas masks, assuredly with a greater emphasis given their position near the front. They were headed to the area of Fleurbaix in northern France which was known as the ‘Nursery Sector’ – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times did not last long. Training continued with a focus on bayonets and the use of gas masks, assuredly with a greater emphasis, given their position near the front.

Battle of Fromelles

The 32nd moved to the front on 14 July and were into the trenches on 16 July for the first time, only three weeks after arriving in France. On the 17th they were reconnoitering the trenches and cutting passages through the wires, preparing for an attack, but it was delayed due to the weather. D Company’s Lieutenant Sam Mills’ letters home were optimistic for the coming battle:

“We are not doing much work now, just enough to keep us fit—mostly route marching and helmet drill. We have our gas helmets and steel helmets, so we are prepared for anything. They are both very good, so a man is pretty safe.”

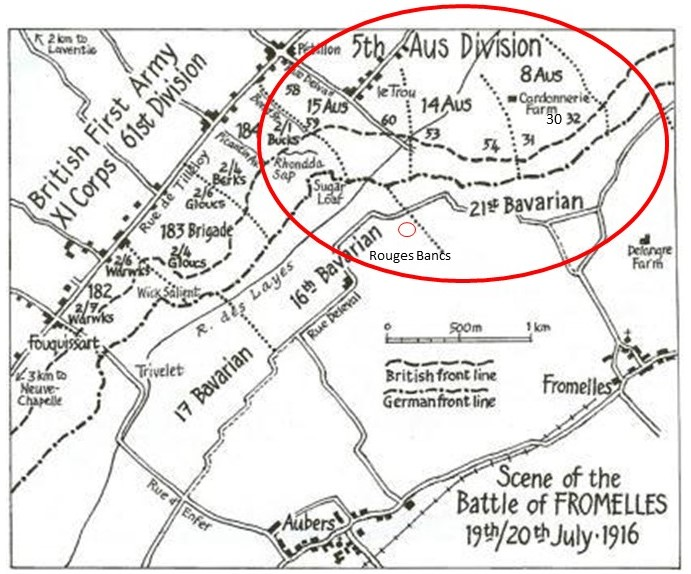

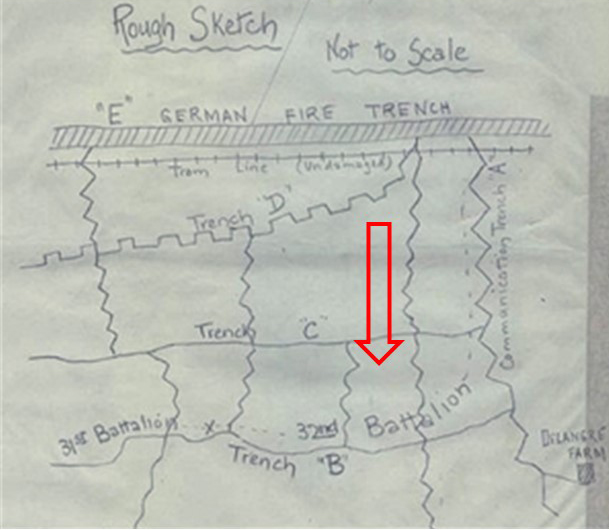

The overall plan was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The 32nd Battalion’s position was on the extreme left flank, with only 100 metres of No Man’s Land to get the German trenches. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 31st Battalion on their right.

However, their position made the job more difficult, as not only did they have to protect themselves while advancing, but they also had to block off the Germans on their left, to stop them from coming around behind them. The Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. All were in position by 5.45 PM and the charge over the parapet began at 5:53 PM.

Maurice’s A Company & C Company were the first and second waves to go with Bert’s B Company and & D the third and fourth.

Based the witness statements of fellow soldier Private Geoffrey M Adamson (665), Bert did not make it far into the battle:

'I saw Sgt. Burbidge ... hit by something just as we were going over the parapet at Fleurbaix. on July 19th. He was right on top of the parapet, and he fell down the other side into a hole in No Mans (sic) Land. We went straight on and left him. I enquired for him after the attack was over, and reported what I had seen. I do not think he was ever found.'

He also said in a further statement, 'On the night of July 19th 1916 I was next to No. 411 Sgt Burbidge[,] we were getting over the parapet of our own trench proceeding to attack a German trench in front. I saw Sgt. Burbidge hit by something which appeared to strike him about the neck. He immediately fell. As far as I know nothing further was heard about this N.C.O.'

While Bert was killed early in the attack, Maurice and the 32nd were successful in their initial assaults and by 6.30 PM were in control of the German’s 1st line system (map Trench B), which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

Unfortunately, with the success of their attack, ‘friendly’ artillery fire caused a large number of casualties. They were able to take out a German machine gun in their early advances, but they were being “seriously enfiladed” from their left flank.

By 8.30 PM their left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and the 32nd was told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

Fighting continued through the night. Up ahead, the Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine gun fire from behind and from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. At 4:00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map).

Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to envelop the soldiers of the 32nd. At 5:30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance the 31st could offer was with rifles:

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

What was left of the 32nd had finally withdrawn by 7.30 AM on the 20th. The initial roll call count was devastating – 71 killed, 375 wounded and 219 missing, including Bert. The final impact was that 228 soldiers of the 32nd Battalion were killed or died from wounds sustained at the battle and, of this, 166 were unidentified.

Lieutenant Sam Mills survived the battle. In his letters home, he recalls the bravery of the men:

“They came over the parapet like racehorses……… However, a man could ask nothing better, if he had to go, than to go in a charge like that, and they certainly did their job like heroes."

Maurice survived the battle and continued serving with the 32nd Battalion until his transfer to the 5th Divisional Transport in 1917. He never did return to Australia, however. He died of influenza in 1919 while stationed in England during the post-war pandemic and is buried at Brookwood Military Cemetery in Surrey.

Where is Bert?

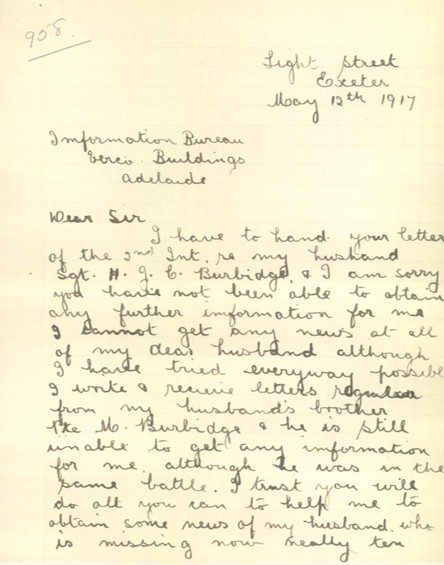

The initial news that Bert was missing did get home quickly but, while the Army and the Red Cross were making extensive efforts to find the missing, no hard news about him followed:

“Mrs. M. A. Burbidge, of Exeter, has been officially informed that her husband (Sergeant H.J.C. Burbidge) was reported missing in France on July 20. Sergeant Burbidge was 27 years of age, and a son-in-law of Senior-Constable Curtin, of Port Adelaide. He was, prior to enlistment, employed by the Chamber of Commerce.”

Maurice made enquiries about his brother to the Army in December 1916:

“I saw him an hour before we went over on the 20.7.16…I have not heard anything official yet only he is on the missing list. I shall be very glad if you will drop me a line letting me know who is the person enquiring after him… I am sorry I am unable to give you any other information regarding him.”

While Pte Geoffrey M Adamson’s statements were clear as to when/where Bert was killed, but if he was killed near the Australian parapet, where was his body? Private Reginald Harbort (1280) 32nd Bn, 7 April 1919 also reported Bert was in No Man’s Land:

'We advanced at Fleurbaix on the night of the 19th, but had to withdraw on the morning of the 20th. During the withdrawal witness saw Burbidge's body in "No Man's Land". On going right up to him he noticed he had been hit in the chest. He was lying on his back with a peaceful look on his face and it would appear he was killed outright. They were being pressed at the time and could not pick up the body. They subsequently held their original front line and some of the bodies were picked up by the Pioneers from "No Man's Land", but Witness could not say whether Burbidge's body was recovered.'

However, Private Roy C. Harrington (344A), 27th Bn (ex-32nd Bn) (patient, War Hospital, Dunston, Northants, England), gave hope that Bert’s body had, indeed, been recovered and given a proper burial:

'Burbridge was killed at Fleurbaix on the 19th July. He is buried in the cemetery at Fleurbaix. I have seen his grave.'

There are no records to support this and Bert remains missing to this day. It took until a Court of Enquiry, held in the field, 12 August 1917, that the AIF pronounced that Bert was 'Killed in Action’.

Aftermath - The Family

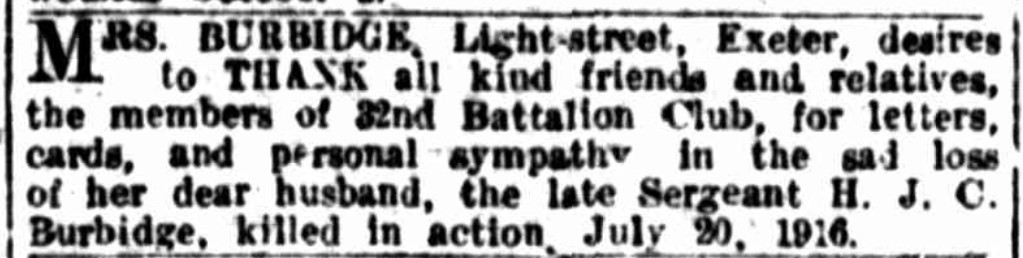

Not long after Bert left for the war, his wife Margaret had moved to Light St, Exeter, South Australia in January 1916. In May 1916 she gave birth to their daughter Monica, who now would never know her father. A few weeks after being notified Bert was missing, Margaret’s anxious wait for news became a prolonged agony of uncertainty. The official Red Cross file records her attempts to gain information, including a heartbreaking letter to authorities in 1917 asking for any updates on her husband’s fate.

Margaret’s connection to her brother-in-law Maurice must have also been of comfort at that time.

Bert has no known grave and is commemorated at the V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial at Fromelles, along with over 1,300 other Australians who died in the battle with no known resting place.

Not only did Bert and Maurice die during the war, their younger brother, Eric Malcolm Burbidge (Service No. 73459), served with the Durham Light Infantry and was killed in action on 24 September 1918, aged 26. Bert’s parents had lost all three of their sons.

Eric is commemorated at the Vis-en-Artois Memorial in France. The men commemorated on this memorial have no known grave and include soldiers from the armies of Great Britain, Ireland, and South Africa.

The boys’ mother, Eva, lived out her life in Chelsea, London, where she had worked as a nurse throughout the war, dying in 1939, aged 71. Their sister, Helen Hope Burbidge, married and also settled in Chelsea.

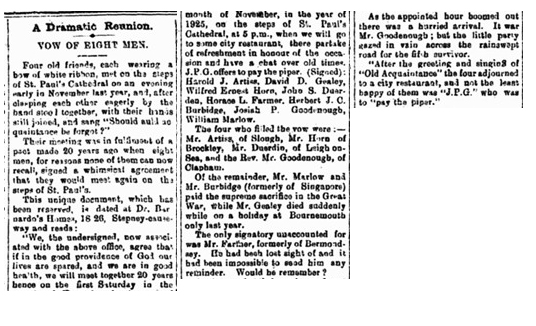

Old Friends Remembered

Ten years after the war ended, in January 1926 a small group of men gathered for a quiet drink in Singapore. These men, all in their thirties or forties now, had once been close friends — young lads who had grown up together on the island in the early 1900s. Before life scattered them across continents, they had made a pact - that no matter what happened, they would meet again one day to share a drink and recall old times. For three of the men, the reunion was bittersweet. Among the empty glasses and reminiscences was the absence of Herbert John Charles Burbidge — “Bert” — their childhood friend who had died at Fromelles.

The reunion, reported briefly in the Western Argus newspaper, carried the weight of memory and mourning. The men remembered Bert’s warmth, his sense of duty, and the adventurous spirit that had taken him from Singapore to England, and eventually to South Australia where he would marry and enlist for war. They drank in his honour, and in the honour of others lost — not just Bert, but also his brothers Maurice and Eric, all of whom also died in service. The article did not name the surviving friends, but the gesture itself — to return, remember, and raise a glass — speaks to the enduring bonds of boyhood and the pain of loss that lingered a decade on.

Can Bert be found?

In 2008, a mass grave at Pheasant Wood that contained the bodies of 250 soldiers was discovered. DNA testing from family members to identify the bodies now in the Pheasant Wood Cemetery has been ongoing and as of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified. Of the 166 originally unidentified soldiers from the 32nd, 41 have been found.

These soldiers have now been given a proper burial and recognition. There are a further 70 soldiers from 250 who were in the grave that are not yet identified. One of them could be Bert. While Bert’s witness statements say he may have been too close to the Australian lines to have been recovered by the Germans and they did not report as having found his ID tag, but without DNA samples, we will never know.

Please contact the Fromelles Association if you have any connection with the Burbidge family.

Family connections are sought for the following soldier:

| Soldier | Herbert John Charles Burbidge (1887-1916) m Margaret Agatha Curtin |

| Parents William Mark Burbidge (1862-1925) Bengal, India and Eva Julie Forrest (1867-1939) born Singapore Died Chelsea, London |

| Siblings | Maurice Norman Henry Burbidge (1891-1919) | ||

| Eric Malcolm Burbidge (1892-1918 | |||

| Helen Hope Burbidge (1897-1986) married Sidney Allan | |||

| Daphne Lillian Burbidge (Half Sister) b1919 India | |||

| Addison Mark Burbidge (Half Brother) (1925-1931) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | John Burbidge (b 1814, d unknown ) and Maria Sherrod or Sherrard (1833-1883) | ||

| Maternal | Charles Edward Forress (1840-1871) and Julia Steward (1844-1936) |

Please note: Burbidge has also been spelt as Burbridge

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).