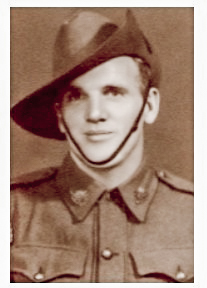

Stanley Sydney SAWERS

Eyes hazel, Hair fair, Complexion fresh

Stanley Sydney Sawers

Can you help find Stanley?

Stanley Sawers’ body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

Stanley may be among these remaining unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in London and Stirling Scotland (via Jamaica)

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for Stanley, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Please contact the Fromelles Association of Australia to find out more.

Early Life

Stanley Sydney Sawers, known simply as Stanley, was born in 1892 at South Melbourne, Victoria, to Henry Thomas (Harry) Sawers (1862-1917) and Emma Jane Sherman (1870-1954). Emma’s family came from London, while Harry’s father Ezekial was born in Jamaica, as were several generations of the planter families who originated from Stirling, Scotland in the 1700s.

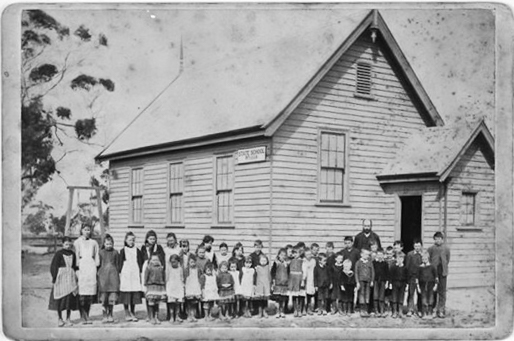

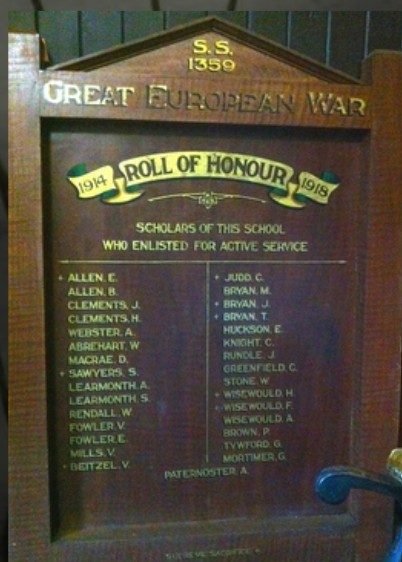

Stanley grew up in the Pakenham South district with his older sister Ida (1890-1967) and younger brother Raymond (1908 - 1991). They attended Pakenham East State School, where Stanley gained a basic education before leaving to work as a farm labourer to support the family. He was known as a quiet, reliable young man with blue eyes and a fair, fresh complexion.

From a young age, Stanley showed a keen interest in marksmanship and became a prominent member of the Emerald Rifle Club. His skill with the rifle and dedication to practice earned him respect among his peers. Rifle clubs were popular and fit in well with the Military’s views at the time:

“In 1911 the attention of the Australian military forces was focused on the roll-out of the universal training scheme. Meanwhile, the rifle club movement very much continued on with its usual programme of annual club, district and State association, and Commonwealth matches.”

“War is not a matter for individuals. Battles are not fought between picked teams, but between battalions, and, therefore, the general standard of marksmanship should be as high as possible.”

At the time war broke out, Stanley had been living with his mother at 6 Wilkinson Street, West Brunswick, working as a labourer, but just prior to the war he was living further out in Emerald and Pakenham South.

Off to War

On 1 November 1915, at the age of 23, Stanley enlisted in Melbourne. Like many young men, his decision was no doubt influenced by his sense of duty to protect the Empire, but also by his years with the Emerald Rifle Club, where he had become a confident marksman and was known as a dedicated member. He was assigned to the 5th Battalion, 14th Reinforcements, and after weeks of basic training, he embarked from Melbourne on 28 January 1916 aboard HMAT Themistocles.

As the ship pulled away from Port Melbourne, families gathered along the pier to wave farewell, not knowing if they would see their sons again. For Stanley, it was a farewell to his mother Emma, sister Ida and seven year old brother Ray. After weeks at sea, Stanley disembarked at Suez, Egypt, on 28 February 1916. With the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five, major reorganisations were underway. On 26 March, Stanley was transferred to the 57th Battalion, but just a week later, on 3 April, he was moved again, to the 60th Battalion, joining them at Ferry Post.

The 60th Battalion had been raised in Egypt on 24 February 1916 at the 40,000-man training camp at Tel-el-Kebir, about 110 km northeast of Cairo. Roughly half of the soldiers were Gallipoli veterans from the 8th Battalion, a predominantly Victorian unit, and the other half were fresh reinforcements from Australia. At Ferry Post they guarded the Suez Canal and continued their training under the hot desert sun. The training was gruelling, with long days doing rifle practice, bayonet drills, route marches, and trench warfare preparation. They remained at Ferry Post until 1 June continuing their training and guarding the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army. Their time in Egypt was not all work, however.

A 5th Division Sports Championship was held on 14 June, which was won by the 60th’s 15th brigade. On 17 June they received orders to begin the move to the Western Front and then were on trains to Alexandria. The majority of the battalion, 30 officers and 948 other ranks, embarked in Alexandria on the transport ship Kinfauns Castle on 18 June 1916. After a stop in Malta, they arrived in Marseilles on 29 June and were immediately put on trains for a three day trip, arriving in Steenbecque in northern France, 35 km from Fleurbaix on 2 July. The men were cheered by French civilians as they passed through towns and villages on their way north, but the cheering faded as they neared the front lines where the impact of the war was more visible. This area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans.

But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. On the 7th they began their move to the front, arriving in Sailly on the 9th. Now just a few kilometres from the front, their training continued, although with a higher intensity, I’m sure. The move to Fleurbaix continued and 60th were into the trenches for the first time on 14 July. Stanley’s training with the Rifle Club had prepared him for marksmanship and discipline, but the not for the realities of the Western Front.

The Battle of Fromelles

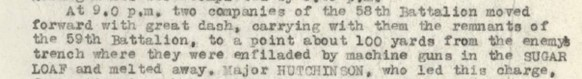

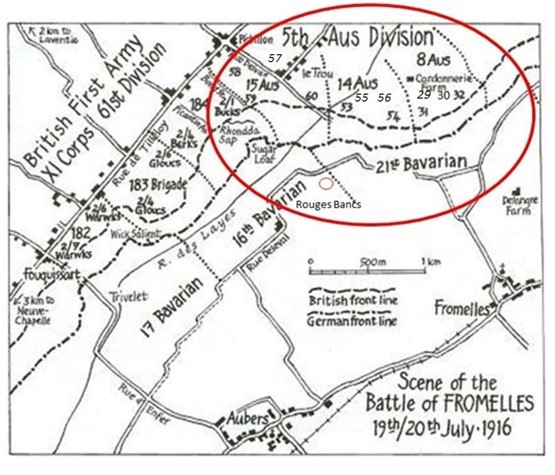

The battle plan had the 15th Brigade located just to the left of the British Army. The 59th and 60th Battalions were to be the lead units for this area of the attack, with the 58th and 57th as the ‘third and fourth’ battalions, in reserve. The main objective for the 15th Brigade was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the other battalions would be subjected to murderous enfilade fire from the machine-guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 59th and 53rd Battalions on their flanks.

The 60th Battalion faced an especially difficult position in the assault, close to the ‘Sugar Loaf’. On 17 July, they were in position for the major attack, but it was postponed due to unfavourable weather. There was a gas alarm, but luckily it was just that. Two days later, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties.

A fellow soldier, Private Bill Boyce (3022, 58th), summed the situation up well:

“What have I let myself in for?”

The Aussies went over the parapet at 5:45 PM in four waves at 5 minute intervals, but then lay down to wait for the support bombardment to end at 6 PM. A & B Companies were in the first two waves, C & D in the next two. Casualties were immediate and heavy. The 15th Brigade War Diaries captures the intensity of the early part of the attack – “they were enfiladed by machine guns in the Sugar Loaf and melted away.”

Private Bassett, who survived the battle, described the horror Stanley and his mates faced in that moment:

“Stammering scores of German machine guns spluttered violently… Hundreds were mown down in the flicker of an eyelid, like great rows of teeth knocked from a comb, but still the line went on thinning and stretching.”

The British 184th Brigade just to the right of the 59th met with the same resistance, but at 8.00 PM they got orders that no further attacks would take place that night. However, the salient between the troops limited communications, leaving the Australians to continue without British support from their now exposed right flank. It was reported that some Australians got to within 90 yards of the enemy trenches. One soldier said:

“he believed some few of the battalion entered enemy trenches and that during the night a few stragglers, wounded and unwounded, returned to our trenches.”

Fighting continued through the night. With known high casualties in the 60th, they were relieved by the 57th Battalion at 7.00 AM. Roll call was held at 9.30 AM.

C.W. Bean later remarked:

“of the 60th Battalion, which had gone into the fight with 887 men, only one officer and 106 answered the call.”

To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The final impact of the battle on the 60th was that 395 soldiers were killed or died of wounds, of which 315 were not able to be identified.

Stanley’s Fate

As described by Stanley’s tent mate and friend Private Leslie Summers (4598) in a witness statement for the Red Cross, Stanley was killed in the initial charge:

“On July 19th about 7 p.m. he saw Sawers hanging over parapet dead. Witness had been wounded and was being carried down the trench. Saw Sawers and stopped, seized his hand and squeezed it, there was no response, it was icy cold. Witness is certain he was dead. Knew him very well, he was witness's mate.”

...“Witness saw soldier hanging over the parapet of our own front line at Fleurbaix. He went up to him, and on examination, found soldier was dead. They were tent mates, and came from Australia together. Does not know what happened to his body.”`

After the Battle

Stanley’s family waited anxiously for news, hoping he might be among the wounded or taken prisoner. While Leslie Summer’s 14 March 1917 reports about Stanley’s fate were clear, it wasn’t until 4 August 1917 that a Court of Enquiry held in the field made the official declaration that Private Stanley Sydney Sawers had been killed in action on 19 July 1916. His death left a deep void in his family.

His father, Harry, who passed away in 1917, had in his death notice as remembering him as the father of “the late Private S. Sawers.” His mother, Emma, never forgot her son, continued to mourn Stanley’s loss for decades by placing annual tributes in newspapers that spoke of her, Ida and Roy’s grief and enduring love. Each year, her words spoke of a son deeply missed, of blue eyes never forgotten, and of love that endured long after the guns of France fell silent.

1931 - SAWERS.— In loving memory of Pte. Stanley Sawers, beloved son of E. and the late H. T. Sawers, who was killed at Fleurbaix 19th July, 1916, loved brother of Ida and Ray.

Noble and kind are our memories of you.

Dear were the years that were only too few.”— Mother

1933 - SAWERS.— In loving memory of Private S. Sawers, beloved son of E. and the late H. S. Sawers, brother of Ida and Bon, killed at Fleurbaix on the 19th July, 1916.

There are memories so fond and true, For ever in our hearts of you;

And I seem to gaze in eyes of blue,

And know in all things you were true.”— Mother

1939 - SAWERS.—In loving memory of Pte. Stanley Sawers, 60th Batt., beloved son of E. and the late H. T. Sawers, loving brother of Ida and Ray. Killed at Fleurbaix, July 19, 1916.

Dearly loved and ever fondly remembered.”— Inserted by Mother

His old club, the Emerald Rifle Club, also honoured him among twenty of their members who served during the war, recognising him as one who never returned:

“Sergeant Edward Ladd and Private Stanley S. Sawers, two prominent members of the Emerald Rifle Club, were recently killed in action in France. No less than 20 members of this club are on active service, which, considering the comparatively small membership, is a fine record.”

Even though he was killed near the Australian lines, Stanley has no known grave. He was awarded the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll.

He is commemorated at:

- V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles (No. MR 7)

- Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, Panel 170

- Emerald Avenue of Honour Plaques,

- Pakenham State School No 1359,

Finding Stanley

After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including two of the 315 unidentified soldiers from the 60th Battalion.

While some members of Stanley’s family have donated DNA, we welcome all branches of Stanley’s family to come forward to donate DNA to ensure we have what is needed to help with his identification.

If you know anything of family contacts, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Stanley’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Stanley Sydney Sawers (1892–1916) |

| Parents | Henry Thomas (Harry) Sawers (1862–1917) and Emma Jane Sherman (1870–1954) |

| Siblings | Ida Louisa Elizabeth (1890–1967) m Robert Henry George Murphy 1913. | ||

| Raymond Ezekiel Petgrave (1908-1991) m Valda Nellie Belcher 1944 |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Ezekiel Petgrave Sawers (1832–1894) and Frances Elizabeth Evans (1832–1908) | ||

| Maternal | George Sherman (1840–1886) and Elizabeth Robb (1842–1912) |

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).