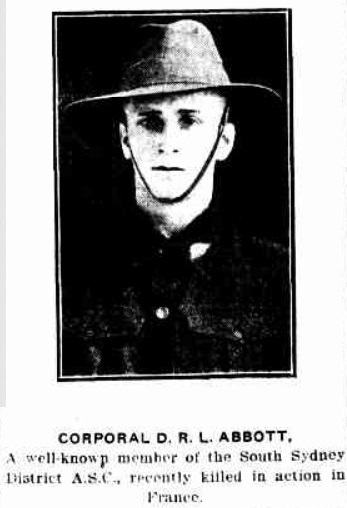

David Roylstone Leslie ABBOTT

Eyes blue, Hair auburn, Complexion fair

Roy Abbott – A Young Life Nobly Ended

Can you help find Roy?

David Roylstone Leslie (Roy) Abbott’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles and there are no records of his burial. A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing. Roy may be among these remaining 70 unidentified men.

There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in Sydney, NSW. See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for David Roylstone Leslie Abbott, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Early Life

David Roylstone Leslie Abbott, known as Roy, was born in Sydney, New South Wales, in 1895. He was the third child of David James Abbott (1870–1933), a Sydney hairdresser, and Margaret Mary (Maggie) Begg (1865–1897). Roy’s early life was marked by both love and loss. His mother died when he was only two years old, leaving his father to raise him and his siblings:

- Richard James Abbott (1889–1892) – who died in infancy

- George Harold Abbott (1891–1942)

- Mildred Gladys “Millie” Abbott (1893–1974)

- Half-sister, Charlotte Rose Abbott (1903–1975), from his father’s second marriage to Harriet R Newby in 1903.

He attended Fort Street High School, one of Sydney’s most prominent public schools, where he was remembered as bright, sociable, and active. As a young man, Roy worked as a boot salesman in Sydney’s bustling commercial heart. He was employed by Edward Fay Limited, popularly known as “The Big Boot Block”, located on the corner of Pitt and Liverpool Streets. The company promoted itself as “The Largest Shoe Store in the Commonwealth.” and was eventually purchased by Coles Myer.

Beyond school and work, Roy enjoyed an active social life. He was a member of the Cyclists’ Union and the Lily Club, a Sydney social and sporting association. His involvement in such groups reflected his outgoing personality and enthusiasm for camaraderie. As in the newspaper articles below, he was clearly missed by these friends:

“Another athlete whose death is announced by cable is Cpl Roy Abbott, who was in the old South Sydney Harriers and also a prominent member of the South Sydney District Amature Swimming club.”

"D.R.L. Abbott, who had risen to the rank of Corporal, a member of the Cyclists’ Union and the old Lily club has been killed in action”

Off to War

Roy enlisted in the AIF on 15 August 1915 at Holsworthy, New South Wales and was assigned to the 15th Reinforcements of the 1st Battalion. During his training he was promoted to Corporal in D Company on 1 December 1915, but when reorganisations moved him to C Company, he was reverted to Private on 15 February 1916, just before his embarkation. He retained this rank through the war. On 8 March 1916, Roy embarked from Sydney aboard the HMAT A15 Star of England. The ship carried reinforcements for several units, bound for Egypt. With the ‘doubling of the AIF’ as it expanded from two infantry divisions to five after the Gallipoli campaign, major reorganisations were underway.

Roy was transferred to the 53rd Battalion on 20 April 1916, while they were at Ismailia. The 53rd was made up of Gallipoli veterans from the 1st Battalion and the new recruits from Australia. The Gallipoli soldiers in the 53rd were not slow in pointing out to whoever would listen that they were the “Dinkums” and the new recruits were the “War Babies”.

Source: - AWM4 23/70/1, 53rd Battalion War Diaries, Feb-July 1916, page 3

Training continued at Tel-el-Kebir, where the men endured long route marches across the sand, musketry, bayonet practice, and field manoeuvres under the desert sun. One soldier recalled the conditions:

“The heat and flies were terrible, but we drilled endlessly and were proud to be part of the Fifth.”

On 16 June when they began the move to the Western Front - 32 officers and 958 soldiers of the 53rd left Alexandria on 19 June on the troopship HMT Royal George, bound for Marseilles, France to become part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front. They arrived in Marseilles on 28 June and immediately entrained for a 62-hour journey north to Hazebrouck before finally marching into the camp at nearby Thiennes in northern France. During their trip it was noted that their ‘reputation had evidently preceded them’, as they were well received by the French at the towns all along the route.

Source - AWM4 23/70/2 53rd Battalion War Diaries February - June 1916, p. 4

This area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. On 10 July, the 53rd entered trenches for the first time. The front near Fleurbaix was anything but calm. Rain flooded the communication trenches, artillery fire harassed supply lines, and the soldiers dug in amid the mud and barbed wire of No-Man’s-Land.

The Battle of Fromelles

On 8 July 1916, the 53rd Battalion began a 30 km march to Fleurbaix and settled into billets there on 16 July. The men knew something was coming. They rehearsed attacks in replica trench systems, inspected bayonets, and watched as huge guns rolled into place behind the lines. Then on 16 July, they moved up for an attack—only to have it postponed due to weather. The delay proved torturous.

Private Jim Granger (4784), a young Dorrigo soldier, described the tension in his dugout:

“The heat and flies were terrible, but we drilled endlessly and were proud to be part of the Fifth.”

On 19 July, heavy bombardments were underway from both sides by 11.00 am. By 4.00 pm the 54th rejoined on their left, and all were in position for battle. Zero Hour was set for 5.45 pm. The Germans, however, were well prepared and opened a massive artillery bombardment at 5.15 pm, causing chaos and many casualties before the Australians had even advanced.

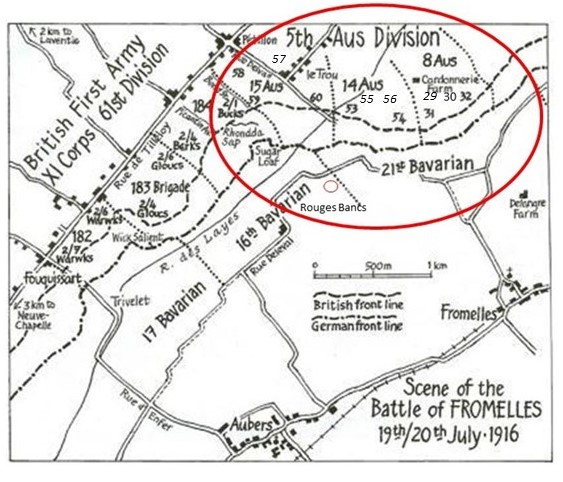

The main objective for the 53rd was to capture trenches to the left of a heavily armed German strongpoint known as the Sugar Loaf. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the 53rd and neighbouring units would be subjected to murderous enfiladed fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 60th and 54th Battalions on their flanks.

At 5.43 pm, the Australians went forward in four waves. Men moved out into No-Man’s-Land and lay waiting until the British bombardment lifted.

Private Arthur Crewes (4755) wrote of the time:

“At 5.43 pm the signal for the charge sounded, and over the top we went into the face of death, shells bursting, machine guns rattling and rifles crackling.”

Then, at 6.00 pm, the German trenches were rushed. Under intense artillery, machine-gun and rifle fire, the 53rd nevertheless advanced rapidly.

Corporal J.T. James of C Company reported:

“At Fleurbaix on the 19th July we were attacking at 6 p.m. We took three lines of German trenches.”

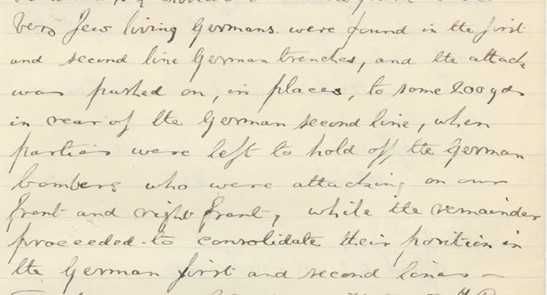

As below, the 14th Brigade War Diary notes that the artillery had been successful and “very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches”, but the attack came at great cost. Within the first 20 minutes, the 53rd lost all its company commanders, their seconds in command, and six junior officers. Source - AWM C E W Bean, The AIF in France, Vol 3, Chapter XII, pg 369

Some of the trenches captured were little more than water-filled ditches, which the Australians hastily fortified to resist counterattacks. On the left, they linked with the 54th Battalion and, with the 31st and 32nd, occupy a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm. But on their right, the 60th had been decimated under fire from the Sugar Loaf and could not advance. This left the 53rd’s flank dangerously exposed.

They held their lines through the night against “violent” attacks from the Germans from the front, but their exposed right flank had allowed the Germans access to the first line trench BEHIND the 53rd, requiring the Australians to later have to fight their way back to their own lines. At 9.00 am on 20 July, orders were received to withdraw. By 9.30 am the survivors had fought their way back to their original lines, retreating “with very heavy loss.”

Source - AWM4 23/70/2, 53rd Battalion War Diary, July 1916, p.7

Of the 990 men who had left Alexandria only weeks earlier, initial roll call showed 36 killed, 353 wounded, and 236 missing.

`“Many heroic actions were performed.”`

Charles Bean later wrote that when he visited the battlefield two and a half years afterwards that he observed a large amount of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The final impact of the battle on the 53rd was 245 soldiers were killed or died from their wounds and, of this, 190 were not able to be identified.

After the Battle

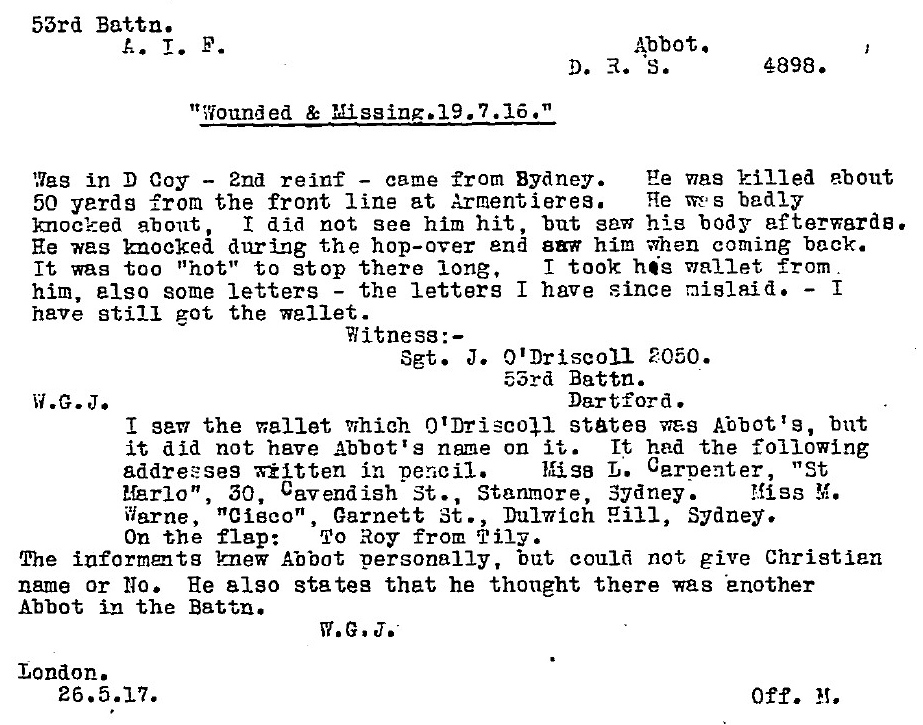

Among those missing was Private David Roylstone Leslie “Roy” Abbott. Based on Red Cross Witness statements, he was killed about 50 yards from the Australian lines during the initial assult. Sgt. John O’Driscoll (2050), also of the 53rd.

Sergeant N.L. Mawson (4821) added, “…Abbott’s Coy., when they all got back all said that Abbot was gone, killed by a shell. Pte. Knight who was near him also told me this.”

Source - AWM - Red Cross Wounded and Missing File – David Roylstone Leslie Abbott - p 4

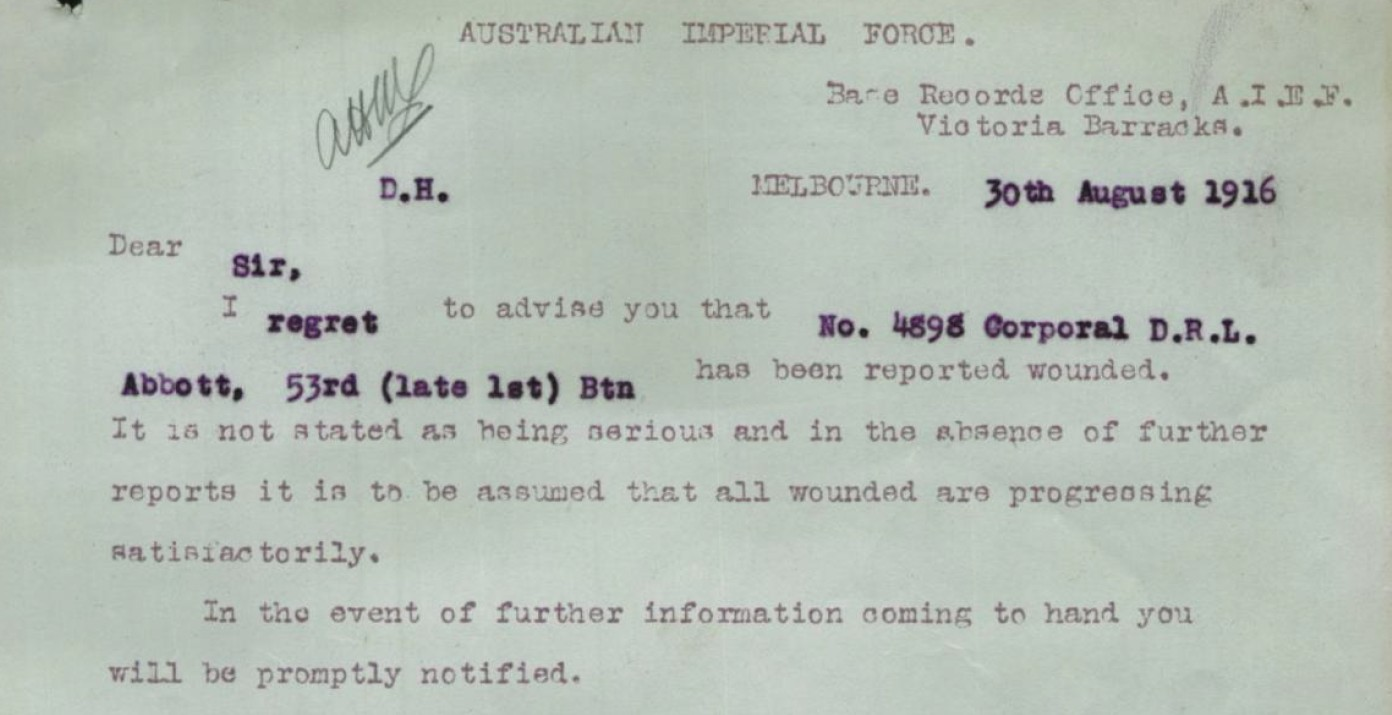

While he was killed close to the Australian lines, the ongoing shelling near Australian lines, the chaos of the battle during the nighttime and with no cease fire after the battle meant that Roy’s body could not be recovered. The Army initially advised his family at the end of August with some very generic (and optimistic) “information” that Roy was wounded. While not untrue, all it really meant was that they did not have any direct information about him. Not much comfort for his family.

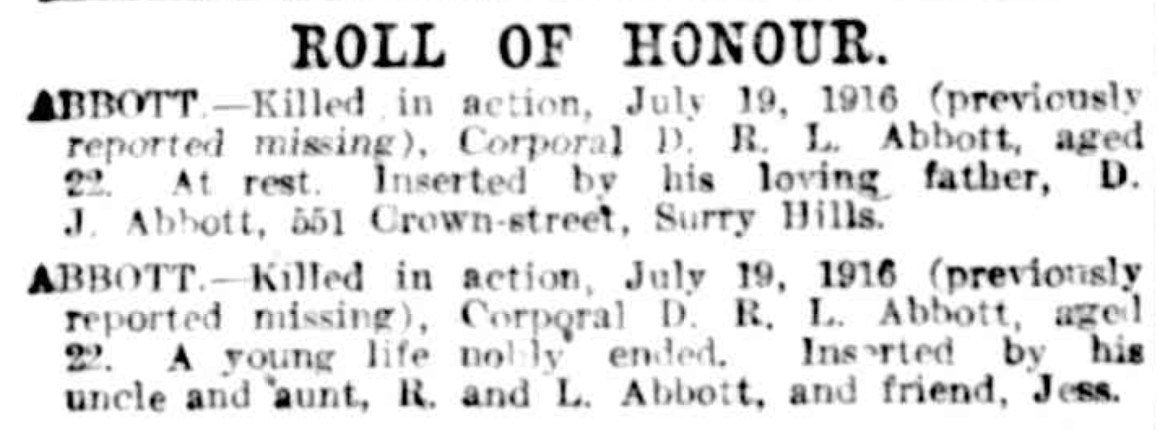

The Army and the Red Cross did undertake extensive searches to find the missing soldiers, but that took time (i.e. statement from Sgt. O’Driscoll is not until 5 May 1917). In December, Roy’s status was revised to “wounded and missing” and this remained until an Enquiry in the Field that was that was held on 2 September 1917 formally declared Roy as having been Killed in Action on 19 July 1916. Tributes from his family in the papers show that he was clearly loved and missed:

“A young life nobly ended.”

Roy was awarded the 1914-15 Star Medal, the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll and he is commemerated at V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery Memorial, Fromelles, France, Panel 6 and Australian War Memorial, Canberra, panel 156.

Finding Roy

Roy’s remains have not been recovered, and he has no known grave. After the battle, the Germans recovered 250 Australian soldiers and placed them in a burial pit at Pheasant Wood. This grave was discovered in 2008 and since then efforts have been underway to identify these soldiers by DNA testing from family members. As of 2024, 180 of the soldiers have been identified, including 15 of the 190 unidentified soldiers from the 53rd Battalion.

We welcome all branches of Roy’s family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in Sydney, NSW. If you know anything of family contacts, please contact the Fromelles Association. We hope that one day Roy will be named and honoured with a known grave.

Please visit Fromelles.info to follow the ongoing identification project and Roy’s story.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | David Roylstone Leslie Abbott (1895–1916) |

| Parents | David James Abbott (1870–1933) born Sydney, NSW; died Glebe, NSW and Margaret Mary “Maggie” Begg (1865–1897) born NSW; died Sydney, NSW |

| Siblings | Richard James Abbott (1889–1892) | ||

| George Harold Abbott (1891–1942) | |||

| Mildred Gladys “Millie” Abbott (1893–1974) | |||

| Half-sister Charlotte Rose Abbott (1903–1975) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Richard Abbott (1825–1888) and Mary Ann Eleanor Hawkins (1835–1891) | ||

| Maternal | James Begg (-1896) and Margaret Mary Attridge (-1884) |

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).